|

Peter "Pete" Wendling (June 6, 1888 to April 7, 1974) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

1913

Soup and Fish Rag [1]1915

Soupirs d'Amour : Love's SighsRockaway Hunt: Fox Trot [2] Hee Haw: Fox Trot [2] Steeple Chase: Pigeon Walk [2] Rackety Coo [3] Jelly Roll: Fox Trot [4] 1916

Honky-TonkBlue Monday: One Step [2] Zig Zag: Fox Trot [5] Pantella: Fox Trot [5] The Call of a Nation [6] Chromatic Rag [7] Yaaka Hula Hickey Dula (Hawaiian Love Song) [8,9] 1917

You're Mamma's Baby [9,10]Over the Top [11,12] I'm Crazy Over Every Girl in France [11,12] Give Me a Little Bit More Than You Gave Reilly [12] Mamma, Mamma, Mamma, I Doubly Do Love You [12,13] Alexander's Back from Dixie with His Ragtime Band [14] 1918

Oh! How I Wish I Could Sleep Until MyDaddy Comes Home [9,10] I Miss that Mississippi Miss that Misses Me [9,10] March On! March On! (With Our Comrades Over There)[14,15] 1919

All I Get is Consolation [6,16]Allah! (You Know Me Al) [6,16] False Faces [16] The Music of the Wedding Chimes [16] When It's Sweet Patootie Time [16] Down by the Meadow Brook [16] Egyptian Butterfly [16,17] Take Me to the Land of Jazz [16,17] Oh! What a Pal Was Mary [16,17] Hello! Lemonade [16,17] Take Your Girlie to the Movies (If You Can't Make Love at Home) [16,17] All the Quakers Are Shoulder Shakers (Down in Quaker Town) [16,17] 1920

What-cha Gonna Do When ThereAin't No Jazz? [16] In Sweet September [16,18] 1921

My Little Sister Mary [16]Monastery Bells [16] 1922

Can He Love Me Like Kelly Can? [9,10]There's an Old Oaken Bucket in Old Nantucket [11] Too Many Kisses Mean Too Many Tears [11,19,20] A Sleepy Little Village (Where the Dixie Cotton Grows [16] Crying for the Moon [16] Old Yeller Dog of Mine [16] Arithmetic Blues [16,19] He Loves It [16,21] Whenever You're Lonesome (Just Telephone Me) [19] Flirt [19] Pleasant Dreams [19] Grandma's Boy [22,23] Those Star-Spangled Nights in Dixieland [24,25] 1923

Papa Blues [16,19]Maxie Jones, King of the Saxophone [16,21,26] Marching Down the Aisle [18,27] Page Paderewski [28,29] You're O.K. Katy With Me [30] Song of the Condemned [31] I'd Rather Fox Trot than Waltz [32] 1924

Home! For the Rest of My Life [19]Wendling/Kortlander Song Folio: [19] New Orleans Fizz (Diminished Syncopation) Silver Screen: Waltz Tosti's Good-Bye: Paraphrase (apologies to F. Paolo Tosti) Flower of Spain (Gold Medal Tango) On Hawaiian Sands (Serenade) Butter Fingers (A Soft Spread) Buck Shots (Somethin' to Shoot At) Old Folks At Home (Swanee River): Paraphrase Steps (A Modern Progression) Rain Drops (Novellette) Left Hand Tricks (six examples for the development of the left hand) Black n' Blue (A Finger Contusion) Hugs and Kisses [33] Oh! How I Wish I Knew [33] The Jefferson Davis [34] 1926

What Good is "Good-Morning"? (There'sMore Good in Good-Night) [4] Blue Bonnet - You Make Me Feel Blue [11,35] Usen't You Used to Be My Sweetie? [11,36] (I Met Her in the Moonlight But) She Keeps Me in the Dark [11,36] Scatter Your Smiles [19] Ain't I Got Rosie [19,36] 1927

Red Lips (Kiss My Blues Away) [11]Lonesome Waltz [11] Whatever You Say [19] (There's Something Nice About Everyone, But) There's Everything Nice About You [37] We Ain't Got Nothin' to Lose [38,39] 1928

Cherie Chilly-Pom-Pom-Pee [11]Don't Keep Me in the Dark, Bright Eyes [11] Starlight and Tulips [11] He's Worth His Weight in Gold [11] Felix the Cat [11,19] Humoreskimo [11,40] In the Sweet Bye and Bye [11,41] Arms of Love [11,41] I'd Like to Ride Away to a Little Hide-Away [11,42] Lady of Love [11,43] The Bee Song (You Never Saw a Bee Being All Alone Without Another Bee Being Around) [31,36] How Long Has This Been Going On? [38] 1929

There's a Four Leaf Clover in MyPocket [14,31] Spring It in the Summer and She'll Fall [31,42] You Are a Pain in My Heart [31,42] That's What I Call Sweet Music [31,42] Blowing Kisses Over the Moon [31,44] Me and the Clock, Tick-i-ty Tock and You [31,44] To Make A Long Story Short, I Love You! [31,44,45] Wonderful You! [31,46] Mary Jane [31,46] Sandman, Wrap Me in a Silver Cloud [31,47] There's Danger In Your Eyes, Cherie! [35,31] 1930

Loose Ankles [31]Dream Avenue [31,35] A Little Bit of Happiness Will Go a Long, Long Way [38,51] What Kinda People Are You? [42,49] Who's Calling You Sweetheart Tonight [48,50] |

1930 (Cont)

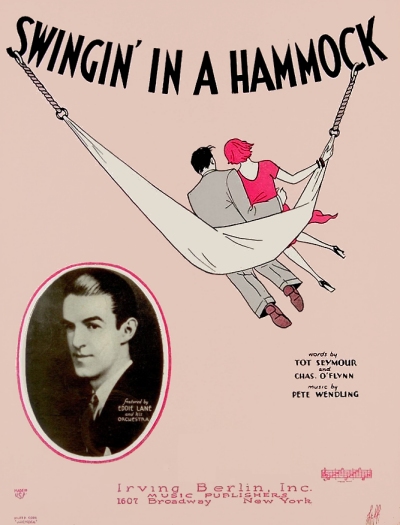

I'll Be Blue Just Thinking of YouFrom Now On [49] I'm Tickled Pink with a Blue-Eyed Baby [50] Just a Little Dance Mam'selle [50] Swingin' in a Hammock [50,52] She's a Very Good Friend of a Friend of a Friend of a Very Good Friend of Mine [50,53] Crying Myself to Sleep [54] It's Easy to Fall in Love [55] If I'd Only Listened to You [55] 1931

Rock Me in a Cradle of Kalua [11]Give Me Your Affection, Honey [11] Thanks to You [21] Without a Warning (You Kissed Me Good-Bye) [42,52] Under the Mistletoe [52] By the Sycamore Tree [56] 1932

Say! Can't You See (What You're Doin' toMe) [9] I'm Sure of Everything but You [50] Sittin' by the Fire With You [50,57] It's All My Fault [50,57] Under My Umbrella [50,57] Did My Heart Beat? Did I Fall in Love? [50,57,58] It Used to Be Me [50,59] 1933

Won't You Say Hello? [11]Three of Us [50,60] 1934

I'm Growing Fonder of You [9,57]Ooh! You Miser You [10] We Were the Best of Friends [10,57] Here Today, Gone Tomorrow [10,57] It's an Old-Fashioned World After All [11,57] I've Got the Funniest Feeling [50,57] Ev'rything is Peaches 'neath the Old Apple Tree [50,57] Rockin' on the Porch [52] High and Low [56] I Believe in Miracles [57] Looks Like a Beautiful Day [57,61] Old Nebraska Moon [62,63] 1935

Two Chairs and a Table [10,57]Nothing Lives Longer than Love [57] Quicker than You Can Say "Jack Robinson" [64] 1936

When the Shadows Grow Longer [56,66]Murder in the Moonlight, Guilty of Love in the First Degree [57] I'm a Fool for Loving You [57] Kissin' My Baby Good Night [57,64] Tell Me With Your Kisses [57,64] Old Forgotten Lullaby [57,65] 1937

Can I Canoe With You? [50,67]I Wouldn't Change You for the World [57,64] The Little Old-Fashioned Music Box [57,64] 1938

Don't Wake Up My Heart [10,57]Ribbons and Roses [10,57] You Took My Heart Walking [57,64] Chimes in the Steeple [57,64] Do You Tell Her Things you Told Me? [57,64] 1942

On the Street of Regret [54]1949

The Story of Annie Laurie [10,57]Frisky Fingers [68] 1954

Mister Midnight [10]1955

I Wonder [10,57]1956

Rich in Love [10,57]ASCAP Unspecified Year

I'm a Sinner [10,57]If You Were In My Shoes [50] Julie O'Dooley [16,31] Oky Doky Tokyo [16] Rollin' Home [50,52] Smile On Dearie [11,57] Sourpuss Hannah [69]

1. w/Harry Jentes

2. w/Milton Ager 3. w/Otto Harbach 4. w/Henry W. Santly 5. w/M. Kay Jerome 6. w/Fred Ahlert 7. w/Ed Gearhart 8. w/E. Ray Goetz 9. w/Joe Young 10. w/Sam M. Lewis 11. w/Alfred Bryan 12. w/Jack Wells 13. w/James Burris 14. w/Lew Colwell 15. w/Ernie Aldwell 16. w/Edgar Leslie 17. w/Bert Kalmar 18. w/James V. Monaco 19. w/Max Kortlander 20. w/W.H. Sandefur 21. w/Grant Clarke 22. w/Herb Crooker 23. w/Jean Havez 24. w/Lew Cantor 25. w/Herman Ruby 26. w/Ted Eastwood 27. w/Billy Rose 28. w/Joseph Samuels 29. w/Larry Briers 30. w/Sam Landers 31. w/Jack Meskill 32. w/Otto Motzan 33. w/James Brockman 34. w/Walter Donaldson 35. w/Harry Richman 36. w/William Raskin 37. w/Arthur Terker 38. w/Benny Davis 39. w/Irving Maslof 40. w/Henri Berchman 41. w/Francis Wheeler 42. w/Al Hoffman 43. w/J.S. Zamecnik 44. w/Billy Mann 45. w/Norman Brokenshire 46. w/Max Rich 47. w/Irving Kahal 48. w/Ben Gordon 49. w/George Whiting 50. w/Charles O'Flynn 51. w/J. Fred Coots 52. w/Tot Seymour 53. w/Frank Flynn 54. w/John Klenner 55. w/Coleman Goetz 56. w/Haven Gillespie 57. w/George W. Meyer 58. w/Benee Russell 59. w/Howard Phillips 60. w/David Lee 61. w/Eugene West 62. w/Cecelia Reeker 63. w/Billy Baskette 64. w/David Mack 65. w/Charles Tobias 66. w/Mitchell Parish 67. w/Jack Betzner 68. w/Sol "Violinsky" Ginsberg 69. w/John Redmond |

Known Discography Known Discography | |

|

1923

Papa BluesPage Paderewski 1926

Someone is Losin' SusanUsen't You Used to Be My Sweetie? Mary Lou I Met Her in the Moonlight |

Matrix and Date

[OKeh 71545] 05/31/1923[OKeh 71637] 05/31/1923 [Cameo 2098] 08/25/1926 [Cameo 2244] 12/09/1926 [Cameo 2245] 12/09/1926 |

Pete Wendling left a perfectly reputable career track as a carpenter for a more dubious career track as a renegade pianist and frequent composer. While for many his name does not stand out, Wendling left a pretty definitive mark on the face of American music of the 1920s through 1940s. He was born on the fabled Lower East Side of New York City, New York, in 1888 to German immigrant parents Philip Wendling and Caroline "Carrie" Wilhelm (shown as Williams in some official sources). Pete was nearly the last of five surviving siblings, including Joseph (12/12/1875), Magdalena "Lena" (5/30/1878), Charles (11/5/1881), and Emma "Hattie" (9/17/1890). One other child, John E., died at age 1 in 1885. For the 1900 census the family was shown as living in Manhattan at 626 East 17th Street #117. Philip and Joseph were listed as laborers, and Charles as a carpenter, a business he would be associated with most of his life. That enumeration erroneously shows Pete with a February birth month, and some of the months for the other siblings are also incorrect. Given that at least the information for Charles is correct, all other demographics are right, and nobody else in the United States closely matched this listing, the family information is assumed to be correct except for some of the birth months. Later biographical references to him being Pete Wendling, Jr., are in error as nothing has been found to support this possibility.

According to a 1924 biography of Wendling, he "discovered" the piano in his parents' home around 1899 or 1900, just as ragtime was starting to gain traction in the New York music world. He then undertook learning as much about the instrument as he could.  A contrasting version from 1927 stated that "When Pete was a youngster, his parents insisted that he study music and Pete selected the piano, figuring that he wouldn't have to carry the instrument to and from lessons. He believed in economizing on energy!" Either way, he took lessons for a short while, but realized that he and his instructor(s) were not on the same general path, so he quit the lessons in his early teens, opting to learn on his own. Being practical, however, Pete also learned the carpentry trade, assumedly either as an apprentice to his brother or at least working with his brother's employer.

A contrasting version from 1927 stated that "When Pete was a youngster, his parents insisted that he study music and Pete selected the piano, figuring that he wouldn't have to carry the instrument to and from lessons. He believed in economizing on energy!" Either way, he took lessons for a short while, but realized that he and his instructor(s) were not on the same general path, so he quit the lessons in his early teens, opting to learn on his own. Being practical, however, Pete also learned the carpentry trade, assumedly either as an apprentice to his brother or at least working with his brother's employer.

A contrasting version from 1927 stated that "When Pete was a youngster, his parents insisted that he study music and Pete selected the piano, figuring that he wouldn't have to carry the instrument to and from lessons. He believed in economizing on energy!" Either way, he took lessons for a short while, but realized that he and his instructor(s) were not on the same general path, so he quit the lessons in his early teens, opting to learn on his own. Being practical, however, Pete also learned the carpentry trade, assumedly either as an apprentice to his brother or at least working with his brother's employer.

A contrasting version from 1927 stated that "When Pete was a youngster, his parents insisted that he study music and Pete selected the piano, figuring that he wouldn't have to carry the instrument to and from lessons. He believed in economizing on energy!" Either way, he took lessons for a short while, but realized that he and his instructor(s) were not on the same general path, so he quit the lessons in his early teens, opting to learn on his own. Being practical, however, Pete also learned the carpentry trade, assumedly either as an apprentice to his brother or at least working with his brother's employer.Given the circumstances under which he was learning the piano, Wendling is reported to have thought of himself as one of the world's worst pianists. However, playing for anybody who would listen, and eventually gaining some traction performing at house parties and school functions, he soon found out from the acclaim that he received that he was better than he thought. He also was a devotee of the many ragtime pianists who plied the trade at Tony Pastor's vaudeville theater on 14th Street in Manhattan, around two blocks from his home. Pete graduated from De Witt Clinton High School around 1906 and while still working some carpentry jobs he secured a position at the Dewey Theater on 14th street, a nickelodeon showing short films mixed with occasional vaudeville olios. Then in 1908 he won the coveted Richard K. Fox trophy for ragtime performance, which master performer Mike Bernard, now a judge for the event, had first secured in 1900 in the National Police Gazette sponsored competition.

This ego boost may have been enough to shift his focus from carpentry to music, but it would be another two years before Pete would be regarded for a position in the music business. The 1910 census showed Pete living with Charles and Minnie Wendling and their two children. Charles was listed as working in a woodwork factory, but Pete had now decided on music as a career, listed as a piano musician. In 1910 or 1911 he was performing at a Boy's Club in New York when he was heard by a staff member of the firm of Frederick A. Mills. Pete was hired as a song plugger for Mills, later moving to Waterson, Berlin & Snyder where there were more opportunities. His reading skills were sufficient for learning pieces, but his playing was well beyond that of the average plugger, giving him an edge.

On June 25, 1911, Pete was married to AnnA Frances Gillen, the niece of New York stage actor Tom Gillen. He potentially connected with her while working in Manhattan theaters with her uncle. Anne was a singer who Pete reportedly accompanied on stage from time to time. She may have also encouraged him to expand his performance base and exploit his talents to a better result. After working the vaudeville circuits in 1911 and 1912, Pete got a great opportunity to play on a vaudeville tour with composer Lewis F. Muir in Britain in 1913 at the London Hippodrome.  As it turned out, they held him captive there for eight consecutive weeks, which was considered a record stint for a pianist in that venue for some time. It was also in 1913 that his name first started to appear on published music, having contributed to the eccentric Soup and Fish Rag with fellow composer and talented pianist Harry Jentes. It was published by a future collaborator of Wendling, George W. Meyer.

As it turned out, they held him captive there for eight consecutive weeks, which was considered a record stint for a pianist in that venue for some time. It was also in 1913 that his name first started to appear on published music, having contributed to the eccentric Soup and Fish Rag with fellow composer and talented pianist Harry Jentes. It was published by a future collaborator of Wendling, George W. Meyer.

As it turned out, they held him captive there for eight consecutive weeks, which was considered a record stint for a pianist in that venue for some time. It was also in 1913 that his name first started to appear on published music, having contributed to the eccentric Soup and Fish Rag with fellow composer and talented pianist Harry Jentes. It was published by a future collaborator of Wendling, George W. Meyer.

As it turned out, they held him captive there for eight consecutive weeks, which was considered a record stint for a pianist in that venue for some time. It was also in 1913 that his name first started to appear on published music, having contributed to the eccentric Soup and Fish Rag with fellow composer and talented pianist Harry Jentes. It was published by a future collaborator of Wendling, George W. Meyer.Wendling's true talents as a performer were soon recognized by those in the industry that were set on capturing such performances for posterity and profit. In 1914 he was engaged by Ampico to play rolls for their Rythmodik line, continuing to work with Waterson, Berlin and Snyder as a plugger. His work with Rythmodik appears to have continued through around mid to late 1916. Many of those rolls had the curious addendum "assisted by W.E.D." Historian Robert Perry has determined that this was Rythmodik producer W.E. Draper, who likely acted in the capacity of an editor with additional input beyond the normal process of note correction.

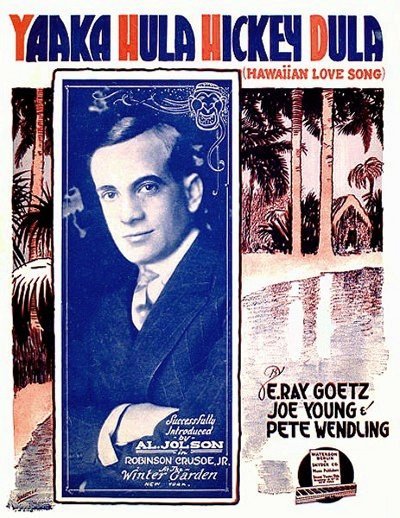

In the process of cutting piano rolls and working with other artists, Pete started to gain a footing in the art of composing, and starting in 1915 a few songs started to trickle out from his pen. With only a couple of exceptions, virtually everything with Wendling's name on it throughout his career would have one or more co-composers, and in some cases Pete also worked as a lyricist. It was a natural development that many of his compositions would find their way to his rolls, as well as to some played by his peers. One of his first enduring hits came in 1916 during a period in which the country was experiencing a Hawaiian song craze. Yaaka Hula Hickey Dula quickly caught the ear of fast-rising entertainer Al Jolson who not only interpolated it into his show Sinbad, but made it is first recorded side of 1916 as well. Another enduring hit was Take Your Girlie to the Movies (If you Can't Make Love at Home).

Pete's services were soon very much in demand. and he was lured to the QRS Piano Roll Company by manager Lee S. Roberts some time in mid to late 1916. This date is not solid, however, as the number of rolls with Pete's name on them as performer were mostly found on the QRS Autograph Automatic label are scant in 1915 and 1916, and may have been recorded by Wendling as a guest artist. Most biographical sources cite 1918 as his starting year with QRS. However, the volume of rolls that start to appear in early 1917 and the lack of current Rythmodik rolls from the same period suggest a much earlier start date. Also, the trade magazines start listing him as a QRS artist as early as January 1917.

Among the earliest to do so, Wendling joined ASCAP in 1916 just two years after the organization was founded. When the call to serve in the war came in 1917, he was left behind to perform and turn out more piano rolls. His 1917 draft record shows him and Anna living on Long Island and still working with Waterson, Berlin and Snyder. Charles Wendling, who Pete was no longer residing with, appeared the following year in the draft as the foreman of a balsa wood plant in New York City. Pete had another hit in 1917 with Alexander's Back from Dixie with His Ragtime Band. In 1918 he would co-write a song that would capture the hearts of many who had soldiers serving in Europe, Oh! How I Wish I Could Sleep Until My Daddy Comes Home. That same year he recorded a number of four-hand rolls with J. Russel Robinson, who would soon be appropriated by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band as their replacement pianist, which curtailed his roll activity for many years.

Wendling got busy after the war, attacking both piano rolls and compositions with great relish. The year 1919 yielded yet another hit for the increasingly confident composer, Oh! What a Pal Was Mary, in addition to the comical Take Your Girlie to the Movies (If You Can't Make Love at Home).

The 1920 enumeration showed Pete and Anna Wendling living at 1012 Summit Avenue #410 in the Bronx, with Pete now declaring himself as a writer of songs. His primary employer in this endeavor was Irving Berlin who had started his own publishing company after separating from Waterson, Berlin and Snyder. There is a definite possibility that he switched to the firm of Jack Mills in 1921, as Mills published many of his pieces in the early 1920s.

|

In 1921 Wendling was in Los Angeles on a vaudeville tour when he was stricken with appendicitis. He recovered from this in short order, but another tragedy was ahead. Details are hard to come by, but Pete and Anna had a child in the early 1920s. According to Pete's nephew, the couple lost their son at a very young age which hit them hard. Pete and Anna them reportedly became nearly a second set of parents for Charles' two children.

Pete's transformation of popular tunes into deftly played piano roll numbers made him one of the favorite performers of QRS, certainly from the consumer's point of view if not internally and within the trade. He created an inordinate number of song recordings for them over the next several years. In May 1923 Wendling was afforded the opportunity to cut two sides for OKeh Records. As a matter of confirmation of his skill, there was very little difference between what was heard on the record and what was present on the corresponding roll of Papa Blues. His work with QRS also helped him start an association with another employee who would eventually be one of the last remaining artists there, Max Kortlander. They composed several tunes together, and in 1924 released a folio of 11 tunes (the cover stated 10) plus some exercises and playing hints. Published by Stark and Cowan, it was stated that the compositions were presented "in various forms, their musical treatment, ornamentations and methods used in Q.R.S. music roll recordings." The partially inaccurate biography of Pete included in the folio did mention that he had moved to Washington Heights in New York City, so things were looking up for him.

Another notable event in 1924 took place in Buffalo, New York, the eventual home of QRS. While player pianos were a well-established and common technology by that time, broadcast radio was still in its infancy. So QRS participated in a concert experiment over station WGR in Buffalo, presenting a concert of both piano rolls and live entertainment that was broadcast in front of a capacity audience at the Statler Hotel. A similar event on a smaller scale had been held in 1922, but this one was much more successful. As noted in the August 2, 1924, Music Trade Review: "Peter Wendling, Max Kortlander and Victor Arden, well-known songwriters arid makers of QRS rolls, were sent by the company to Buffalo to head the program. Their piano selections were followed by deafening applause from the audience and hundreds of letters from fans expressed particular interest in these three artists. Henry Murtagh, organist at Lafayette Theatre and one of the best-known theatre organists in the country, presided at the organ. The string quartet from the Buffalo Athletic Club and Joseph Dombrowski's Orchestra gave several popular dance selections... The three composers and artists sent from New York by the Q R S Co., Messrs. Kortlander, Arden and Wendling, visited the trade following the concert and witnessed hundreds of sales of their rolls and autographed many rolls for purchasers." How much would one of those rolls be worth today? Priceless.

Pete was the first to admit that he was only a performer for QRS, not a music or roll editor by any stretch. His input consisted of doing one or more takes on a markup piano, which simply put pencil marks on a roll as he played. The editing was then undertaken by QRS experts, including Kortlander and the legendary J. Lawrence Cook. It is necessary to understand that in his capacity as an editor, Cook was exposed, both aurally and visually, to the unique qualities of each performer's style and their tricks and traits.  This helped him gain the ability to convey these traits to virtually any performance he wanted, and often times a performer's name was put on a roll even if they did not fully participate. To get around this technicality, "as performed by" could also be used to express that it was an emulation.

This helped him gain the ability to convey these traits to virtually any performance he wanted, and often times a performer's name was put on a roll even if they did not fully participate. To get around this technicality, "as performed by" could also be used to express that it was an emulation.

This helped him gain the ability to convey these traits to virtually any performance he wanted, and often times a performer's name was put on a roll even if they did not fully participate. To get around this technicality, "as performed by" could also be used to express that it was an emulation.

This helped him gain the ability to convey these traits to virtually any performance he wanted, and often times a performer's name was put on a roll even if they did not fully participate. To get around this technicality, "as performed by" could also be used to express that it was an emulation.There were a few profiles done on Pete in the trade papers in the 1920s. One of them from 1925 concerns his transition to QRS as follows: "When [Wendling] attained prestige ten years ago as a composer, he was signed up by a player-piano company to make rolls. Pete wanted to record blues, but the recording manager said the public would not buy that sort of stuff as it "carried too many mistakes." [Since piano rolls were edited, the author can only ascertain that this curious reference is to blue notes or leading grace notes.] Later Pete signed with QRS. The recording manager of this company was thoroughly familiar with the changes in popular music and said he wanted blues - and the mistakes. Pete was paid $3 for the first piano roll he recorded, but now he receives many times that amount for each recording."

Another biographical source explains that Pete had a dynamic sense of humor that matched his playing style. As conveyed by New Zealand roll collector and restorer Robert Perry: "QRS artist Ursula Dietrich-Hollinshead told the story of Wendling and another star pianist, Phil Ohman accompanying her to the train station as she prepared to leave on one of the QRS promotional tours. She was impressed by their kind attentions as they took the conductor aside and whispered to him, since she assumed they wanted her to have an exceptionally pleasant trip. The conductor was too solicitous, however, and watched her every move for hours, until she asked him what the problem was. Her two 'friends' had told the conductor that she was mentally very unstable, and might explode at any minute!"

There are varying reports of how, why and when Pete Wendling and QRS parted ways. The account of J. Lawrence Cook found in the extraordinary Billings Rollography (Volume 3) was that he was in the elevator one day in 1925 when Lee Roberts informed Pete that his services were no longer needed because of lagging sales. This, however, does not properly align with a number of other factors. In fact, QRS sales were extremely strong in 1925 and 1926, both peak years for the player piano industry. The quantity of rolls with Pete's name on them for those years also might possibly exceed what could have been done by Kortlander and Cook alone in addition to all the other rolls they were producing, since arranging took considerably more time than editing. A contradictory 1927 advertisement from QRS found on the same page of Billings Vol. 3 states that Pete had been very busy for the company, and been recording so many rolls that there had been no time for compositions. Indeed, searches turned up no copyrights for Pete in 1925 and very few in 1926. It also makes little sense that they would fire their star artist at his peak. Pete himself claimed that he worked at QRS from 1919 to 1929.

Four more recorded sides were cut on the Cameo Records label in August and December 1926, and had Wendling not been working so hard for QRS during this period there may have been more. It is possible and even likely that some unissued sides were cut, but the matrices are unknown to date, and no additional recordings have been located.

It is entirely probable that Wendling left QRS in 1927, not 1925, and if that is the case, it would better align with the beginning of the sales slump that would almost sink the company over the next decade. Whether Pete left under a cloud owing to artistic differences is something that has not been made clear, even though it would better explain his retreat from QRS. Cook was evidently able to emulate his style well enough by this time to create a few additional rolls with his name on them, as Wendling rolls with a QRS label continued to appear into 1928, albeit some may have still been played by the credited artist.

|

The advent of sound films offered new opportunities for virtually everybody in the music business, with the exception of movie pianists in small town America. In return, the film industry saw benefit in aligning itself with good musicians, and most of the early sound films featured music in some way. One 1927 documentary/revue shot late in the year and titled Words and Music went inside the offices of Tin Pan Alley, and featured many well-known publishers, artists and composers. It gave Pete an opportunity to perform briefly in the same movie that included colleagues George Gershwin, W.C. Handy, Harry Von Tilzer, Ray Henderson, Lew Brown, Bud G. DeSylva and James V. Monaco among others. Produced and assembled by press agent S. Barret McCormick of Pathé, it is unclear if any intact copies of this film exist in the 21st century. During the transition Wendling was also heard infrequently on the radio in New York, mostly on station WMCA.

There was always composing to attend to, and 1928 through 1930 saw a surge of new Wendling and friends compositions. Among those who had joined forces with on a frequent basis were lyricists and composers George W. Meyer, Edgar Leslie, Alfred Bryan, Sam M. Lewis and Charles O'Flynn. But he was hardly limited by that inner circle, working with no less than 69 other collaborators over the years. Many of his songs were now used in sound movies, and one of the projects he became involved with in late 1929 was the film Puttin' On the Ritz, working with Harry Richman who also provided many of the songs for that movie that supplemented the Irving Berlin title tune. Pete's association with a publisher is unclear through this period, and his name appears under a few different logos. Peter and Anna were not found in the 1930 census, leaving open the possibility that they had traveled to California briefly while he was writing for a film, or perhaps off to Europe.

|

Aside from composing, little is known of Pete's activities in the 1930s. However, he was consistent in turning out pieces throughout most of the Great Depression. In 1932, when composer Sid Romberg took over the Song Writer's Protective Association which was formed to secure equitable copyright protection and profits, Pete was elected to the main council headed by Irving Berlin, and was joined by Alfred Bryan, Irving Caesar, Ray Henderson, Harry Warren and Joe Burke. His name appears in the Racing Forms of 1938 through 1940, as there was a race horse bearing his name frequently running in races around the country. It appears that although he was not the owner of the steed, who did manage a few first through third showings, he did have some financial interest in it. However, it appears that the real last name of this particular horse was "also ran."

Another Wendling investment during the Great Depression was in the Times Square restaurant opened by boxer Jack Dempsey in 1935. There were a number of copyright renewals made in the 1930s and 1940s of his earlier material, with Wendling's name applied as the owner under the new registration. Both the 1940 enumeration and his 1942 draft record showed the Wendlings living at 617 W. 168th Street, and with Pete still active as a composer of music in theater and radio, but self-employed by this time. At some point over the next three or so years he moved to California where he was reportedly under contract to a film studio there, a deal for which details are hard to come by. By the late 1940s he and Anna were back in New York City. They were found there in the 1950 census with Pete still claiming to be a songwriter with his own business.

While the flow of songs nearly stopped in 1938, a few Wendling/Lewis selections came out over the next 14 years. In fact, his last known composition, Rich In Love, composed with Lewis and Meyer, became a hit for crooner Pat Boone in 1956. After that time the composer, now approaching 70, retired to a quiet life with Anna in New York, potentially living off his royalties, although under difficult financial circumstances towards the end. The last known sighting of him before his death was in 1961 when he celebrated his 50th Wedding Anniversary with Anna. They spent the next decade and more in a small Manhattan apartment. The composer and piano roll artist finally succumbed to the effects of several strokes in April 1974, followed closely by Anna within three months. They are buried in St. John's Cemetery in New York City, but there is no monument at their grave site.

Wendling was briefly honored by a short obituary in the New York Times and mentions from ASCAP. However, Pete Wendling is more remembered many years later by player piano enthusiasts who listen to his captivating rolls, or sheet music collectors who see his name appearing often on a wide variety of very melodic tunes.

Thanks should be extended to performer and historian Andrew Barrett for prompting this biography and providing some good information. Others with valuable input include New Zealand roll expert Robert Perry, historian and performer Bob Pinsker, and performer Vincent Johnson. In addition to their knowledge, most of the information presented here on Wendling was collected by the author through public records, music industry periodicals, QRS archives, newspapers and music publications.