There are a lot of mysteries surrounding the origins and fate of African-American blues pianist Will Ezell. Some will be addressed here, but some unfortunately will still remain either questionable or simply lost to history.

The first of these has to do with his birthplace, something that would better explain his earlier musical influences. While Fullerton, Louisiana has been cited, this singular reference comes from a 1972 conversation with blues guitarist Jesse Thomas, who included that information in a sentence about Ezell. Thomas was at least 15 years younger, and did not meet Ezell until late in Will's career. There is another reference to him being from East Texas in the same published source. Such conflicting information has to logically lean more towards concrete findings than word of mouth, so any origin of Ezell that suggests a Louisiana birthplace and upbringing is very suspect. Both a 1917 and 1942 draft record appear to provide the most correct information and initial lead on Ezell, citations of which were not found in any other source while researching this article. Texas was also shown as his place of birth in the 1950 census, which was released in 2022. This author's findings ended up being directly in line with research done by Alex van der Tuuk in 2003.

Will Ezell was born in Brenham, Texas, around 70 miles northwest of Houston, on December 23, 1892 (not 1896 as is often reported). This puts him in East Texas within range of Louisiana, and in the heart of the early barrelhouse blues culture. He was one of six children born to day laborer Lorenza Ezell and his wife Rachel (Pinchback) Ezell, including Lula (2/1883), Coy (2/1885), Joseph (3/1888), Lorenza Jr. (7/1894) and Rachel (6/1898). The family was shown living in Brenham in the 1900 census. Little else is known about Ezell's upbringing. Rachel died at some point between 1901 and 1910 as Lorenza showed as widowed and working in the Oklahoma oil fields in the 1910 census. Will started playing in barrelhouses as an itinerant pianist in the early to mid-1910s. This lifestyle may be the most likely reason for not being to accurately locate him in the 1910 or 1920 Federal census records.

His June 1917 draft record places Ezell in New Orleans, Louisiana, living at 212 Erato Street near Lafayette Square, a mile from the French Quarter. He was working as a self-employed musician, and indicated a wife and child, although claimed no exemption from possible service. There is no record of him being inducted for service. Will was described as short and slender. There are many mentions of Ezell being in Louisiana at this time, which when aligned with his known death date and the death certificate information in Chicago, make this an absolute match.

Over the next few years he continued to work at gin mills, rent parties and various labor venues, most notably the river sawmill camps of Louisiana and East Texas. These camps contained the origin of the barrelhouses, usually a shack made from a railroad box car that used barrels for tables. Such places also functioned as brothels and gambling dens, and the presence of a pianist also made it into a dance hall of sorts. The hard left hand playing style quickly developed out of ragtime bass into something much more dynamic, necessary to overcome poorly maintained pianos and the high noise levels that were often found in such quarters. Many of the pieces were blues-based, making it easier to simply create new melodic lines over an otherwise boilerplate left hand pattern. At the time it was still called ragtime, but would eventually become known as boogie-woogie.

It was during these wanderings in the early 1920s that Ezell reportedly teamed up on occasion with blues singer Elzadie Robinson. She came originally from Shreveport, Louisiana, and had performed through Eastern Texas and Louisiana, even up the Mississippi River to St. Louis, Missouri. Performer Knocky Parker also remembers hearing Ezell at the Lone Star Saloon in Dallas sometime around 1922 to 1925, Robinson was known to have also performed in that town. The two of them would build up both a rapport and repertoire that would serve them well later in the decade.

More than one source puts Will's arrival in Chicago, Illinois, from Louisiana as around 1925, which predates his recording career by just a little bit. Many southern musicians had migrated to Chicago over the past seven years, including Joseph "King Oliver, Louis Armstrong, and Ezell's better known peers Hersal Thomas and James Hemingway. He played in both Chicago and Detroit, Michigan, and became friends with pianists Arthur "Blind" Blake and Charlie Spand. They often gathered early in the week at Blake's apartment to exchange ideas and just play for fun before running off to their respective gigs through the weekend.

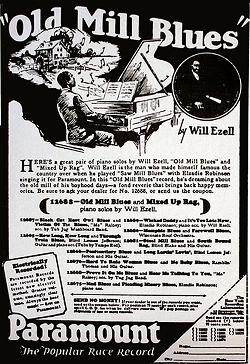

Late in 1926 Ezell started working at Paramount Records. The company was founded nearly a decade prior in Grafton, Wisconsin, as part of the Wisconsin Chair Company to supplement their phonograph cabinet business, which developed from supplying Edison with cabinets to making their own phonographs. Most of their early output suffered from bland content and poor quality pressings. However, they had been providing Midwest pressing for Black Swan Records of New York, and when that African-American owned company went under, Paramount purchased it, giving them an instant entry into the limited by lucrative business of "race records." Between 1922 and 1926 their reputation in this regard had grown, as had complaints about their uneven quality pressings, which had some effect on the unique content.

Still, Paramount provided good opportunities for negro blues players in Chicago that were not readily available elsewhere, and musicians like Ezell quickly signed up to record for them.  In spite of their Wisconsin headquarters, they had a studio in Chicago as well, which is how many of the early blues and boogie players were able to lay down tracks for posterity. Ezell was, therefore, among the first, but not the first, pianist to record boogie-woogie styled sides. After his Sawmill Blues was recorded in 1926 by singer Bernice Duke in October, 1926 (it is questionable whether Will was at the piano for this track) he started to lay down backing tracks and some solo efforts that were among the core of Paramount's best products of the late 1920s.

In spite of their Wisconsin headquarters, they had a studio in Chicago as well, which is how many of the early blues and boogie players were able to lay down tracks for posterity. Ezell was, therefore, among the first, but not the first, pianist to record boogie-woogie styled sides. After his Sawmill Blues was recorded in 1926 by singer Bernice Duke in October, 1926 (it is questionable whether Will was at the piano for this track) he started to lay down backing tracks and some solo efforts that were among the core of Paramount's best products of the late 1920s.

In spite of their Wisconsin headquarters, they had a studio in Chicago as well, which is how many of the early blues and boogie players were able to lay down tracks for posterity. Ezell was, therefore, among the first, but not the first, pianist to record boogie-woogie styled sides. After his Sawmill Blues was recorded in 1926 by singer Bernice Duke in October, 1926 (it is questionable whether Will was at the piano for this track) he started to lay down backing tracks and some solo efforts that were among the core of Paramount's best products of the late 1920s.

In spite of their Wisconsin headquarters, they had a studio in Chicago as well, which is how many of the early blues and boogie players were able to lay down tracks for posterity. Ezell was, therefore, among the first, but not the first, pianist to record boogie-woogie styled sides. After his Sawmill Blues was recorded in 1926 by singer Bernice Duke in October, 1926 (it is questionable whether Will was at the piano for this track) he started to lay down backing tracks and some solo efforts that were among the core of Paramount's best products of the late 1920s.Ezell was soon considered the flexible go-to guy at Paramount, as he could quickly adapt to accompanying nearly anybody, his initial role with the label. Among the first he worked with was Lucille Bogan, who rechristened herself as Bessie Jackson within a few years. Bogan, whose songs bordered on raunchy at times, and were inherently about sex, prostitution, alcohol or drugs, had already been recorded in 1923, but was now in a slump. She moved to Chicago and took an apartment near Ezell and Paramount. Will accompanied her on Sweet Petunia, a song by Harry Charles that was full of double-entendres and would became a short-term hit. But their association soon went well beyond just a couple of recorded sides and outside dates, as the pair reportedly became involved for a short time. As later relayed by Charles, Bogan's husband Nazareth brought divorce proceedings against her for the affair, but they ultimately reconciled and remained married at least into the early 1940s.

During 1927 Will backed other singers on a total of four additional dates (perhaps more, but written records are sketchy). He gained the trust of Aletha Dickerson who became the self-appointed recording manager of the Chicago branch of Paramount in 1928 following the departure of J. Mayo Williams. Will worked as an on-the-spot arranger and pseudo-producer for many dates between 1928 and 1931, likely with her blessing. He also likely recommended some of his colleagues, particularly Charlie Spand, who recorded for Paramount between 1929 and 1931. However, in late 1927 Will was also allowed to "go solo" on the label, cutting several boogie and blues-tinged piano tracks into early 1929. Among those that remain as standouts were the Mixed Up Rag and Heifer Dust.

While many of Ezell's pieces are at least somewhat original, others were clearly assembled from components of other compositions and recordings. This includes Bucket of Blood and West Coast Rag. The latter was literally comprised of strains from the West Coast, most notably Jay Roberts' The Entertainer's Rag. Even in his boogie pieces he quoted from performers like Jimmy Blythe, who had proceeded him to record with that particular style. He was still regarded as original and versatile by other Chicago pianists, and remembered fondly by Eurreal "Little Brother" Montgomery who had also come up through the lumber camp barrelhouses.

Quality was still a continuing issue with Paramount releases, be it from uneven recordings or poorly maintained equipment, or just noisy surfaces. During a refitting of the Chicago studios, Paramount artists co-opted the fabled Gennett Records studio in Richmond, Indiana.

The sessions cut here by Charlie Spand, Baby James, "Blind" Roosevelt Graves and Ezell are among the highest quality released by Paramount, and the studio itself may have lent a different energy to the recordings. These were nearly the last that Ezell would be involved in, other than a compilation by the "Paramount All Stars" late in the year, featuring snippets of pieces by different artists on the label.

|

Among the duties evidently either handed to or taken on by Ezell was handling of special needs of some of the artists and management at Paramount. Indeed, it has been reported that when Paramount blues guitarist and singer "Blind Lemon" Jefferson died in December 1929, Ezell personally escorted the body back to their native Texas where he was buried on January 1 or 2, 1930. Texas also played into another aspect of Ezell's livelihood. Some studios, including Paramount, often allowed for travel expenses incurred to make it to a recording date. It was not uncommon for some artists to exaggerate their travel just a bit. Ezell was no exception, and reportedly claimed travel from Texas on more than one occasion, even though he lived just blocks from the Paramount office. There seemed to have been little complaint, however, given his talents and contributions.

Will was still performing in Chicago in the early 1930s, and was known to have been present at some sessions in 1930 and 1931 at Paramount, but is apparently only heard on two cuts accompanying Sam Tarpley. The company was in trouble, and in 1931 had closed the Chicago studio, choosing to record in Grafton, Wisconsin instead. The Great Depression hit the record industry hard, and given that race records targeted the statistically most impoverished demographic of the United States, their audiences eroded even sooner than those who bought more mainstream popular tunes. Dickerson bailed from the sinking ship, and this appears to have shown her to be the best point of contact between Paramount and its black performers, as most of them seem to have literally disappeared from view and hearing range for a while.

After the Paramount deal collapsed, Ezell went back on the road, including to his old stomping grounds Louisiana where performer Clarence Hall remembers playing with him in 1931. Otherwise, reports of his wanderings, even though he was likely still based in Chicago, are scant at best. While he was mostly invisible for the remainder of the 1930s, researcher John Steiner wrote that Cripple Clarence Lofton, who owned the Big Apple Tavern on South State Street near 47th, reportedly hosted Ezell, Charlie Spand, Leroy Garnett and other former Paramount blues performers over the years on his stage. However, given the context of his statement it might have also been during the years of World War II.

The 1940 census showed Will living at 359 W. Oak Street in Chicago, lodging with a Pauline Rogers. He was working as a watchman for the Chicago street repair project, which at that time was run by the WPA (Work Projects Administration) formed as part of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's New Deal legislation of the mid-1930s. Ezell's 1942 draft record showed him working at the Crane Technical School, also run by the WPA. His role there was unclear, but he was likely an either a watchman or perhaps part of the maintenance staff. Will was now living across the street at 368 W. Oak in Chicago, and gave the widowed Mrs. Rodgers as his reference. They were around the same age, but their relationship was not revealed in searches on either party, and only suggested by the next record. That would be the 1950 enumeration taken in Chicago, which shows Will living alone with a status of separated, and still listed as a musician. The next confirmable information that appears on Will Ezell is that of his death in Chicago in 1963 at age 70. He was living just a few blocks from the Delmark Records office, another label that has continued to support jazz and blues since 1953, and around the corner from Delmark founder Bob Koester's important niche store, the Jazz Record Mart (since moved to a newer location). Sadly, there were no notices in the newspaper obituaries or the trades.

Will Ezell's musical legacy is relatively small but not insignificant, and there are a couple of nice collections of his Paramount recordings available on CD. Any further information on the life and activities or whereabouts of Will Ezell is welcome, as always, and anything verifiable will be credited.

Compositions/Discography

Compositions/Discography