While the sheer bulk of ragtime era piano rags and syncopated songs came from the Eastern half of the United States, there was still some activity in that area in the 1900s and 1910s in the West, particularly in the San Francisco Bay Area, which is also largely where the ragtime revival of the late 1940s started a new interest in the genre. Among those that became somewhat of a star in the West, with a couple of pieces in particular, was a man who did it as perhaps more of a hobby or creative outlet than as a career. Walter Herzer was the youngest of five children born to German immigrant Hugo George Herzer and his French-born wife Elizabeth Ulrich, both who had come to the U.S. in the early-to-mid-1860s. His other siblings, born in San Francisco as was Walter, included Henry Herman (2/10/1874), Emily (5/1876), Hugo George, Jr. (12/3/1878), and Isabelle Marie (8/1883). Hugo, Sr., tried out several different careers, many working for the city of San Francisco, eventually becoming a tax assessor in the 1890s. In the 1900 census he claimed himself as a capitalist, while still working for the tax assessor's office in various roles.

Wallie, who had a propensity for music, also had good sense not always present in musicians, and had a "plan A." Most likely in league with his parents, he decided on a career in a more stable field, and at around age 16 joined the insurance firm of Christensen, Edwards & Goodwin as a clerk. It is also reported that he spent a short amount of time with the firm of Gutte and Frank, although San Francisco city directories from 1901-1904 don't directly support this. He remained with Christensen and Goodwin for many years learning the business, going along even as Edwards dropped out of the firm in the mid-1900s. Along the way, however, now earning a solid living, Wallie decided to expand his horizons and release some of his own music out into the world.

It is also reported that he spent a short amount of time with the firm of Gutte and Frank, although San Francisco city directories from 1901-1904 don't directly support this. He remained with Christensen and Goodwin for many years learning the business, going along even as Edwards dropped out of the firm in the mid-1900s. Along the way, however, now earning a solid living, Wallie decided to expand his horizons and release some of his own music out into the world.

It is also reported that he spent a short amount of time with the firm of Gutte and Frank, although San Francisco city directories from 1901-1904 don't directly support this. He remained with Christensen and Goodwin for many years learning the business, going along even as Edwards dropped out of the firm in the mid-1900s. Along the way, however, now earning a solid living, Wallie decided to expand his horizons and release some of his own music out into the world.

It is also reported that he spent a short amount of time with the firm of Gutte and Frank, although San Francisco city directories from 1901-1904 don't directly support this. He remained with Christensen and Goodwin for many years learning the business, going along even as Edwards dropped out of the firm in the mid-1900s. Along the way, however, now earning a solid living, Wallie decided to expand his horizons and release some of his own music out into the world.Herzer's first known publication was The Rah Rah Boy!!, a college-themed piano rag. The initial copyright and publication was facilitated by Herzer and his arranger, Eugene Brown, but it would eventually be picked up by the firm of Jerome H. Remick in New York once Wallie got some traction as a composer. The title most likely referred to Yale or a similar institution, although this inference was likely more the work of cover artist Leland Stanford Morgan than of Herzer himself. Morgan, who until 1910 worked at the same insurance firm before striking out as an artist, provided at least two other covers for Herzer. In 1909 Wallie brought out the song My Portola Maid, referring either to the inland town about 180 miles northeast of San Francisco, or more likely the San Francisco theater of the same name, and possibly even to a particular girl he knew. This was also copyrighted by Herzer and self-published. The 1910 census showed Wallie living with his sister Isabelle and her husband William J. Matherson. He was listed as an insurance clerk, while Matherson was a commercial traveler for a manufacturer.

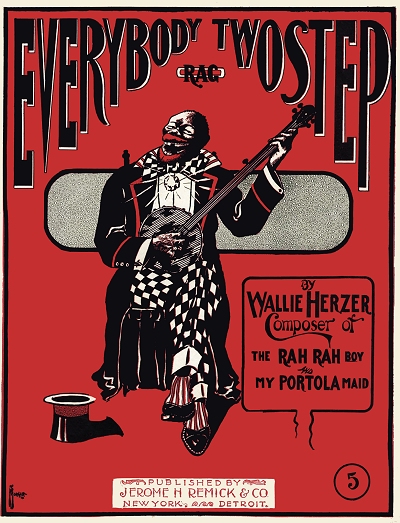

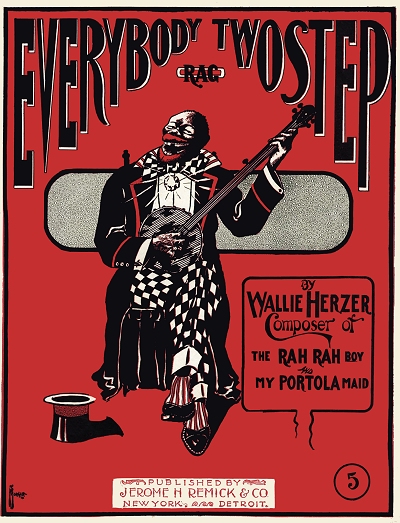

In 1910, Herzer finally struck a vein of California musical gold in a world dominated by East Coast and Midwest composers and publishers. Everybody Two-Step, again initially self-published, seemed to resonate with the local buying public, and soon caught the attention of the Remick firm. Sensing a hit, they bought up Everybody Two-Step and Wallie's earlier works in 1911, issuing them on a national basis. The piece gained further attention in 1912 when it became one of the earliest ragtime piano recordings as executed by the brilliant New York performer Mike Bernard on Columbia. It was also logically arranged for dance orchestras, and issued on copious piano rolls. Following their usual course, the Remick management had lyrics added to the piece that same year by Earle C. Jones, one of the staff writers, so they could sell it as a popular song. Famous vocalist Billy Murray instantly covered it. Both versions did well, and thousands of copies still exist in collections and antique malls around the United States.

Following their usual course, the Remick management had lyrics added to the piece that same year by Earle C. Jones, one of the staff writers, so they could sell it as a popular song. Famous vocalist Billy Murray instantly covered it. Both versions did well, and thousands of copies still exist in collections and antique malls around the United States.

Following their usual course, the Remick management had lyrics added to the piece that same year by Earle C. Jones, one of the staff writers, so they could sell it as a popular song. Famous vocalist Billy Murray instantly covered it. Both versions did well, and thousands of copies still exist in collections and antique malls around the United States.

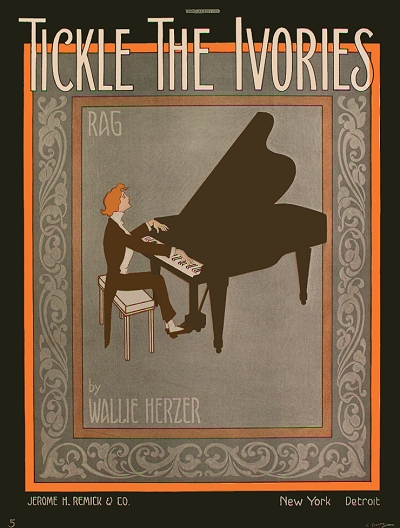

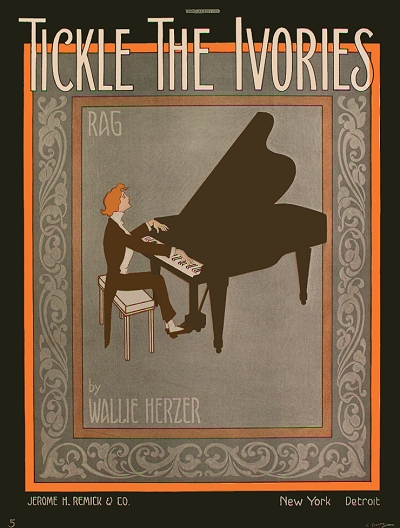

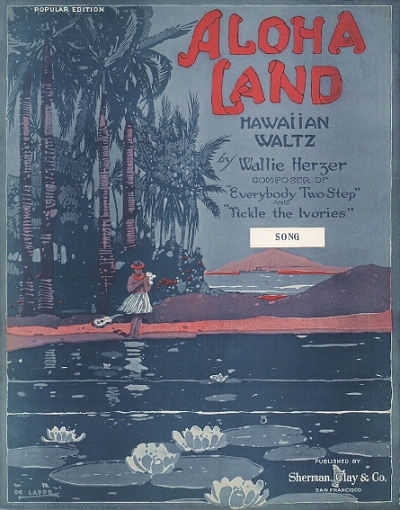

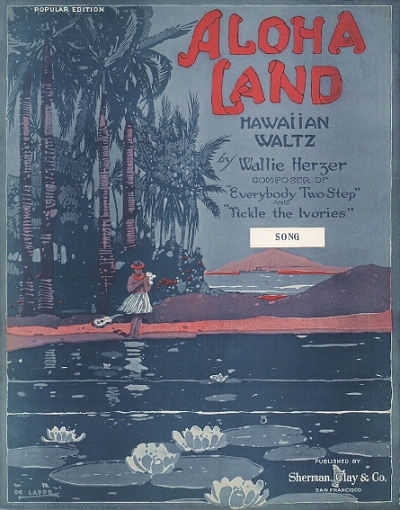

Following their usual course, the Remick management had lyrics added to the piece that same year by Earle C. Jones, one of the staff writers, so they could sell it as a popular song. Famous vocalist Billy Murray instantly covered it. Both versions did well, and thousands of copies still exist in collections and antique malls around the United States.On May 4, 1910, Wallie was married to Sylvia Scalmanini (sometimes seen as Silvia) in San Francisco. Her father had been one of the so-called Forty-Niners who had come to the Bay Area during the famous gold rush of 1849. By this time, he owned a vineyard and winery east of the city, with a footprint in San Francisco. Wallie and Sylvia's daughter Caterina Harriet was born in 1911. After basking in his success for a time, while advancing in his career as an insurance company clerk, Herzer followed up in 1913 with Tickle the Ivories. It was quickly snatched up by Remick, and also turned into a song the same year. Both were moderately successful for Herzer and Remick. Less so was Let's Dance, also a 1913 Remick issue. In December of 1914, following the self-publication of the hesitation waltz Dance with Me, Wallie's next release was Get Over Sal, this time published by fellow composer Charles Neil Daniels [formerly of Kansas City, Missouri] in San Francisco. The title came from an older song calling on the name of a slow drag dance, and the lyrics had double meaning as not only the dance, but also the gal you can't get over. After issuing nothing in 1915, he called on the current craze of Hawai'ian song, bring out his own entry, Aloha Land

All through this time Wallie apparently had a bead on what was what in the competitive music world, particularly on the West Coast, for which the publishing business was in some ways isolated from the vigorous enterprises in the Upper Midwest and the East. Rather than strike out to be a musician, he continued to advance in his other chosen avocation, continuing to work for Goodwin as a manager after Christensen dropped out in the mid-1910s, which was reinforced by his draft record taken during the last call on September 12, 1918. Just prior to that, probably working during evenings and weekends, Wallie concocted a musical comedy called Woman's Ways, providing music to a libretto by San Francisco writer Susan Conleigh Posner. While it was copyrighted in August of 1917, it is unclear if a production of the work was ever staged. After that, it would over two decades before he had another work submitted for copyright.

The 1920 census showed the Herzers living on Vallejo Street in San Francisco with Sylvia's widowed mother Katerina Scalmanini and her sister Norma. Wallie was the only one in the household who had employment. He made a change that year, going to the insurance firm of Bentley & Waterman for the next three years. Then he would become a manger with Glen Falls Insurance Company, where he would remain for the rest of his working career, primarily as a manager of their city department. By 1930, he was doing well enough that for the enumeration, the Herzer/Scalmanini residence was able to afford a household servant, even several months into the Great Depression. Katerina died in the mid-1930s, and the Herzers became empty-nesters, moving to Pacific Heights by 1938. The 1940 census had him listed as a salesman for Glens Falls, even though city directories showed him to still be a manager. The songwriting itch had hit Wallie after their move to a new home, and he wrote and copyrighted at least four songs, one of them being a plug for his home city. However, they were evidently never published, suggesting that there may have been more, and that some of them actually may have been sitting around for some time. There would be no more.

He made a change that year, going to the insurance firm of Bentley & Waterman for the next three years. Then he would become a manger with Glen Falls Insurance Company, where he would remain for the rest of his working career, primarily as a manager of their city department. By 1930, he was doing well enough that for the enumeration, the Herzer/Scalmanini residence was able to afford a household servant, even several months into the Great Depression. Katerina died in the mid-1930s, and the Herzers became empty-nesters, moving to Pacific Heights by 1938. The 1940 census had him listed as a salesman for Glens Falls, even though city directories showed him to still be a manager. The songwriting itch had hit Wallie after their move to a new home, and he wrote and copyrighted at least four songs, one of them being a plug for his home city. However, they were evidently never published, suggesting that there may have been more, and that some of them actually may have been sitting around for some time. There would be no more.

He made a change that year, going to the insurance firm of Bentley & Waterman for the next three years. Then he would become a manger with Glen Falls Insurance Company, where he would remain for the rest of his working career, primarily as a manager of their city department. By 1930, he was doing well enough that for the enumeration, the Herzer/Scalmanini residence was able to afford a household servant, even several months into the Great Depression. Katerina died in the mid-1930s, and the Herzers became empty-nesters, moving to Pacific Heights by 1938. The 1940 census had him listed as a salesman for Glens Falls, even though city directories showed him to still be a manager. The songwriting itch had hit Wallie after their move to a new home, and he wrote and copyrighted at least four songs, one of them being a plug for his home city. However, they were evidently never published, suggesting that there may have been more, and that some of them actually may have been sitting around for some time. There would be no more.

He made a change that year, going to the insurance firm of Bentley & Waterman for the next three years. Then he would become a manger with Glen Falls Insurance Company, where he would remain for the rest of his working career, primarily as a manager of their city department. By 1930, he was doing well enough that for the enumeration, the Herzer/Scalmanini residence was able to afford a household servant, even several months into the Great Depression. Katerina died in the mid-1930s, and the Herzers became empty-nesters, moving to Pacific Heights by 1938. The 1940 census had him listed as a salesman for Glens Falls, even though city directories showed him to still be a manager. The songwriting itch had hit Wallie after their move to a new home, and he wrote and copyrighted at least four songs, one of them being a plug for his home city. However, they were evidently never published, suggesting that there may have been more, and that some of them actually may have been sitting around for some time. There would be no more.By late 1941, the Herzers had moved to Burlingame, south of San Francisco, where Wallie ran a branch office for Glens Falls. That same status was echoed in the 1950 census, showing him as a building value estimator. He maintained that office until at least the mid-1950s, by which time ragtime was becoming popular again, thanks to the Rudi Blesh and Harriet Janis book They All Played Ragtime, the efforts of some San Francisco jazz groups and pianists, and Los Angeles labels like Capitol Records. Everybody Two-Step and Tickle the Ivories were recorded, and occasionally even got airplay. However, it appears that Wallie's participation in the revival was minimal at best, leaving it to the local pros like Wally Rose, Burt Bales and Paul Lingle. In 1955, Sylvia passed away and Wally, now 70, went into semi-retirement, moving to Menlo Park, just a bit further southwest. He remained active as an insurance agent until at least 1959, at least according to city directories. Wally died in late 1961 at age 76, leaving a substantial legacy of customers and their families who had been well-cared for thanks to his insurance acumen, and a dedicated group of ragtime fans who knew him only as the composer of a couple of very fine and happy piano rags, ensuring toe tapping and smiles. In the end, that sounds like a win-win scenario.

Compositions

Compositions