Early Years

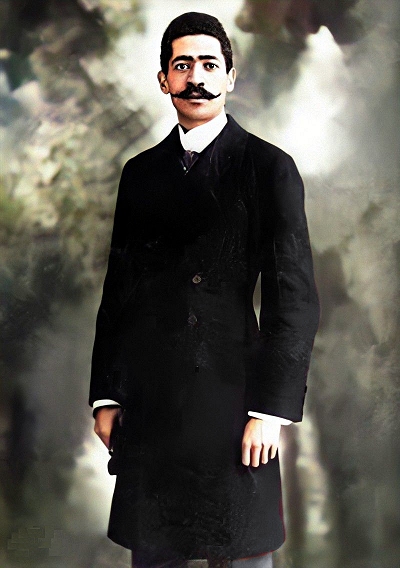

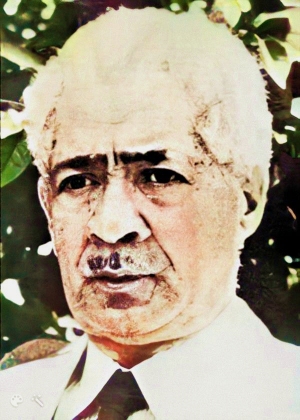

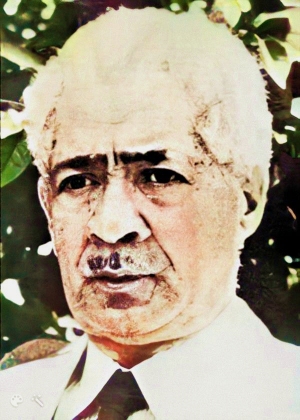

Will Marion Cook was born as William Mercer Cook into a life of at least some privilege in Washington, DC, in early 1869, less than four years after the end of the Civil War, and perhaps within a year of Scott Joplin (real birth date unknown). Both would prove to have similar musical aspirations, but the latter with a decidedly gentler approach. William was one of three brothers born to mulatto parents John H. Cook and Isabel "Belle" Hickman, the others being John H., Jr. (1867) and Oliver (1873). The 1870 census showed John, Sr., working as a clerk in the recently formed Freedmen's Bureau. A graduate of Oberlin College in Ohio, he would soon become the first dean of Howard University Law School following his graduation from that institution. Both Will's father and grandfather were musicians at some point, the latter being a slave fiddler on a Virginia plantation prior to the Civil War. John died of tuberculosis in 1878. The 1880 census taken in DC showed the widowed Belle with her three children, also caring for her younger brother, sister, and sister-in-law, working as a teacher in the District of Columbia school system. As she had graduated with a music degree from the Oberlin College Conservatory in 1865, it is likely she taught music both publicly and privately, and did moderately well for her family at that. However, by 1881 the burden would prove to be more than she could manage.

The family was disbursed, and Will was sent to Chattanooga, Tennessee, to his grandparent's home for three years. While there he was taught to play the violin, or "fiddle," by his grandfather, and took to it with a near-obsessive zeal. In 1884 at the tender age of 15, Will was sent to live with an aunt in Oberlin, Ohio, and by 1886 was attending the music conservatory there, specifically to study violin in addition to music theory under Professor Amos Doolittle. His progress was such that Doolittle recommended to Belle that her son receive advanced training in Europe.

While she was concerned about how to fund this expensive proposition, help came from no less than noted civil rights activist Frederick Douglass. He organized a fund-raising concert in Washington at the First Congregational Church in the summer of 1888, raising enough money to at least start Will on his wa to Europe.

|

So it was that in the fall of 1888, Will Cook, now 19 and a full six feet in height (according to his passport), departed for Germany where he spent nearly two more years training at the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin, Germany, to study harmony, counterpoint, and piano under the esteemed Professor Joseph Hoachim. In 1890, he came back to the United States where he made his public performance debut as a full-fledged virtuoso. That same year, Will took on the leadership of a chamber orchestra organized by Douglass, sending it on tour, and giving Cook a taste of leadership and ownership of his ability, and perhaps even some responsibility as a representative of the Negro race. Within another two years was composing serious works for violin and orchestra. By this time he had dropped Mercer from his name, adopting Marion instead.

Another boost to Will's growing ego came in 1893 when Douglass arranged to put him in charge of a musical event at the World's Columbian Exposition of that year held in Chicago. He was reported to have written an opera based on Harriet Beecher Stowe's controversial play Uncle Tom's Cabin. However, some of the updated content of Will's work made organizers uneasy, and it was dropped from the program. While he was in Chicago that August, any visits to the Exposition were likely as a guest, not a performer. As he was playing violin at various venues in Chicago during that month, it is probable that he got some exposure to the early stirrings of ragtime melodies and cakewalks.

It is important to note that Cook took both his music and himself very seriously, and to that end perhaps felt some entitlement to be recognized for his abilities alone, instead of how good he was for his race. He also, at this point, did not appear to be leaning toward a career in popular music composition. However, that attitude either changed, or simply emerged by the mid-1890s,as the Cakewalk was coming to the fore; the harbinger of a new kind of music that was on the horizon. It was music of his race, but also music with the potential to be elevated to a new level, and to be used as a means to get himself more exposure as a serious composer.

instead of how good he was for his race. He also, at this point, did not appear to be leaning toward a career in popular music composition. However, that attitude either changed, or simply emerged by the mid-1890s,as the Cakewalk was coming to the fore; the harbinger of a new kind of music that was on the horizon. It was music of his race, but also music with the potential to be elevated to a new level, and to be used as a means to get himself more exposure as a serious composer.

instead of how good he was for his race. He also, at this point, did not appear to be leaning toward a career in popular music composition. However, that attitude either changed, or simply emerged by the mid-1890s,as the Cakewalk was coming to the fore; the harbinger of a new kind of music that was on the horizon. It was music of his race, but also music with the potential to be elevated to a new level, and to be used as a means to get himself more exposure as a serious composer.

instead of how good he was for his race. He also, at this point, did not appear to be leaning toward a career in popular music composition. However, that attitude either changed, or simply emerged by the mid-1890s,as the Cakewalk was coming to the fore; the harbinger of a new kind of music that was on the horizon. It was music of his race, but also music with the potential to be elevated to a new level, and to be used as a means to get himself more exposure as a serious composer.Having met Negro baritone Harry T. Burleigh while performing at a classical concert in Chicago, Will was encouraged to go to New York City the following year where Burleigh placed him in the sights of another serious musician. It was there that Will spent some time learning from Czech composer Antonin Dvorak at his National Conservatory of Music. Cook did not regard Dvorak all that highly, and ended up studying under Professor John White at the same school for much of the year. He then joined the traveling stock company of Bob Cole for a season. Hired as their composer for special material, Cook had similar disdain for Cole, but for opposite reasons, as he saw Dvorak as too musically pompous and Cole as too musically unsophisticated. The feud between Cook and Cole would continue for some time after he left the company to play for the concert stage instead. During this period he had his earliest popular songs published in Washington, DC.

There was, according to a later account by composer and bandleader Edward "Duke" Ellington, an incident that possibly tipped the scales for the increasingly frustrated musician. After Will played an 1896 solo concert in the esteemed venue of Carnegie Hall (although several possible venues have been suggested by others), a New York reviewer wrote that Cook was definitely "the world's greatest Negro violinist," Cook reportedly responded with his characteristic frustration and indignant temper:

Dad Cook took his violin and went to see the reviewer at the newspaper office. "Thank you very much for the favorable review," he said. "You wrote that I was the world's greatest Negro violinist." "Yes, Mr. Cook," the man said, "and I meant it. You are definitely the world's greatest Negro violinist." With that, Dad Cook took out his violin and smashed it across the reviewer's desk. "I am not the world's greatest Negro violinist," he exclaimed. "I am the greatest violinist in the world!" He turned and walked away from his splintered instrument, and he never picked up a violin again in his life.

Even though he actually did play it on a few more select occasions, as noted at times in the newspapers over the next two decades, Will largely turned away from the violin around that time, studied more harmony and counterpoint, and set out to be recognized in a more permanent way than the occasional concert could do. To help him in that regard, Cook found one of the more interesting poets of color and of negro dialect, one who was known by many around the country, Paul Laurence Dunbar.

Becoming a Serious Composer of Color

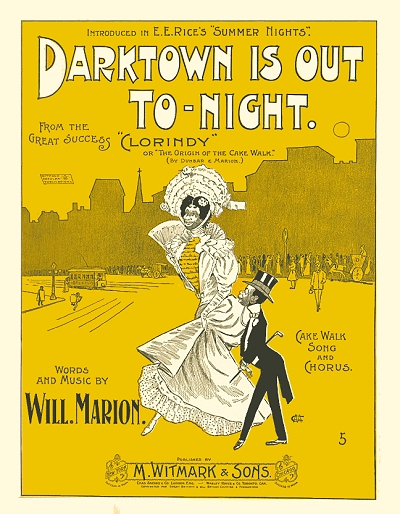

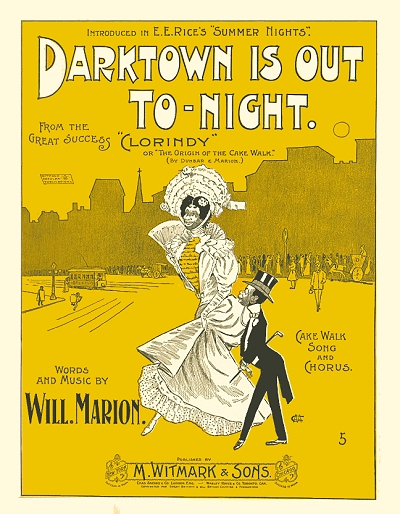

It was allegedly in one ten-hour session that Cook and Dunbar set out to conquer the serious musical stage. The end result was Clorindy: The Origin of the Cakewalk. Two things emerged from this union of the two men. First was a brilliant work that evoked many Negro themes while advancing their cause through carefully crafted libretto and music. The second was a reinforcement of a reputation that Will was quickly earning as a difficult and unpleasant individual to work with. It should be noted that it was staged on a rooftop theater, rather than on an indoor stage, as the owners of the theaters in Manhattan were not yet ready to "legitimize" a Negro production in a proper venue. Cook managed to cajole his way into a forced audition at the Casino Theater Roof Garden, which was reluctantly accepted with some insistence from the Garden's orchestra leader, John Braham. It opened in early July with leading Negro singer Ernest Hogan as the star.

Two things emerged from this union of the two men. First was a brilliant work that evoked many Negro themes while advancing their cause through carefully crafted libretto and music. The second was a reinforcement of a reputation that Will was quickly earning as a difficult and unpleasant individual to work with. It should be noted that it was staged on a rooftop theater, rather than on an indoor stage, as the owners of the theaters in Manhattan were not yet ready to "legitimize" a Negro production in a proper venue. Cook managed to cajole his way into a forced audition at the Casino Theater Roof Garden, which was reluctantly accepted with some insistence from the Garden's orchestra leader, John Braham. It opened in early July with leading Negro singer Ernest Hogan as the star.

Two things emerged from this union of the two men. First was a brilliant work that evoked many Negro themes while advancing their cause through carefully crafted libretto and music. The second was a reinforcement of a reputation that Will was quickly earning as a difficult and unpleasant individual to work with. It should be noted that it was staged on a rooftop theater, rather than on an indoor stage, as the owners of the theaters in Manhattan were not yet ready to "legitimize" a Negro production in a proper venue. Cook managed to cajole his way into a forced audition at the Casino Theater Roof Garden, which was reluctantly accepted with some insistence from the Garden's orchestra leader, John Braham. It opened in early July with leading Negro singer Ernest Hogan as the star.

Two things emerged from this union of the two men. First was a brilliant work that evoked many Negro themes while advancing their cause through carefully crafted libretto and music. The second was a reinforcement of a reputation that Will was quickly earning as a difficult and unpleasant individual to work with. It should be noted that it was staged on a rooftop theater, rather than on an indoor stage, as the owners of the theaters in Manhattan were not yet ready to "legitimize" a Negro production in a proper venue. Cook managed to cajole his way into a forced audition at the Casino Theater Roof Garden, which was reluctantly accepted with some insistence from the Garden's orchestra leader, John Braham. It opened in early July with leading Negro singer Ernest Hogan as the star.Overall, Clorindy was a success during the 1898 season, albeit mostly with its expected target audience, which were the blacks of New York City. It received fine reviews in mainstream papers as well, so managed to hook in some curious white theater-goers and those with an interest in the music itself. In spite of the good reviews, Cook's musically educated mother was evidently nonplussed with Clorindy. She reportedly cried after hearing it, lamenting her son's evident turnabout from high classical to low popular music forms, saying to him, "I've sent you all over the word to study and become a great musician, and return such a nigger!" This both hurt and inspired him to elevate the status of Negro music by infusing it with classical music ideals and paradigms, making it more sophisticated while not denying the source material as coming from his race.

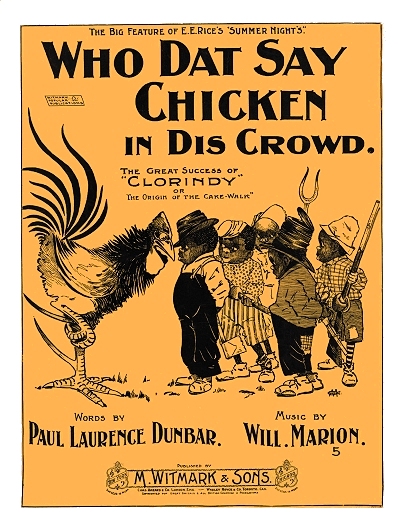

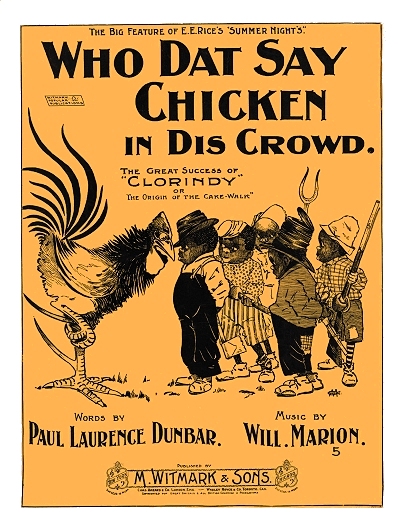

Some of the pieces from Clorindy were published. In fact, it was Isadore Witmark who, as Witmark later recalled, was approached by Cook about a month before the work was debuted asking for the publisher's assistance with getting it staged in exchange for publication rights and all of the royalties. Witmark agreed to help, but also insisted that Cook keep the royalties. However, Cook told a different story, saying that Witmark informed him that he was perhaps delusional to think that any audience on Broadway (or on a rooftop above it) would be interested in hearing Negroes sing in a professional production, much less buy the music afterwards. The truth lay somewhere in between those two accounts, and the sheet music was a moderate seller, most notably helped by the song Who Dat Say Chicken in Dis Crowd.

Undaunted by criticism and emboldened by success, Cook followed Clorindy with the "one act operetto" [sic] Jes' Lak White Fo'ks. As with Clorindy it was largely a Negro story, but with Cook's own libretto for the most part, which pushed forth his own political and social agenda. Staged in 1899 it did not do very well, creating friction between Will and pretty much anybody who criticized the work. Among his most vocal critics was Bob Cole, who had enjoyed some success as a songwriter up to that time. In spite of that success, Cook had evidently found many opportunities during his time with Cole's stock company to belittle his employers work as the product of a limited Southern musical education. This did not help his relationship with Dunbar either. When Will realized that he needed Dunbar's help to retool Jes' Lak White Fo'ks with a better libretto, he evidently asked writer James Weldon Johnson to broker a deal between the two. According to Johnson in his autobiography:

As with Clorindy it was largely a Negro story, but with Cook's own libretto for the most part, which pushed forth his own political and social agenda. Staged in 1899 it did not do very well, creating friction between Will and pretty much anybody who criticized the work. Among his most vocal critics was Bob Cole, who had enjoyed some success as a songwriter up to that time. In spite of that success, Cook had evidently found many opportunities during his time with Cole's stock company to belittle his employers work as the product of a limited Southern musical education. This did not help his relationship with Dunbar either. When Will realized that he needed Dunbar's help to retool Jes' Lak White Fo'ks with a better libretto, he evidently asked writer James Weldon Johnson to broker a deal between the two. According to Johnson in his autobiography:

As with Clorindy it was largely a Negro story, but with Cook's own libretto for the most part, which pushed forth his own political and social agenda. Staged in 1899 it did not do very well, creating friction between Will and pretty much anybody who criticized the work. Among his most vocal critics was Bob Cole, who had enjoyed some success as a songwriter up to that time. In spite of that success, Cook had evidently found many opportunities during his time with Cole's stock company to belittle his employers work as the product of a limited Southern musical education. This did not help his relationship with Dunbar either. When Will realized that he needed Dunbar's help to retool Jes' Lak White Fo'ks with a better libretto, he evidently asked writer James Weldon Johnson to broker a deal between the two. According to Johnson in his autobiography:

As with Clorindy it was largely a Negro story, but with Cook's own libretto for the most part, which pushed forth his own political and social agenda. Staged in 1899 it did not do very well, creating friction between Will and pretty much anybody who criticized the work. Among his most vocal critics was Bob Cole, who had enjoyed some success as a songwriter up to that time. In spite of that success, Cook had evidently found many opportunities during his time with Cole's stock company to belittle his employers work as the product of a limited Southern musical education. This did not help his relationship with Dunbar either. When Will realized that he needed Dunbar's help to retool Jes' Lak White Fo'ks with a better libretto, he evidently asked writer James Weldon Johnson to broker a deal between the two. According to Johnson in his autobiography:...Cook persuaded me to use my good offices to have Dunbar collaborate with him another piece, a full-length opera to be called The Cannibal King... For Jes Lak White Folks... Cook wanted Dunbar's touch and, still more, his name again. But the great success of the first piece was not due along to Dunbar, nor was the partial failure of the second piece due alone to Cook. In Clorindy, New York had been given its first demonstration of the possibilities of Negro syncopated music, of what could be done with it in the hands of a competent and original composer. Cook's music, especially his choruses and finales, made Broadway catch its breath. In Jes Lak White Folks, the book and lyrics were not so good, nor was the cast; and, naturally, the music was not such a startling novelty. I did my best to persuade Paul to do the book and lyrics for The Cannibal King, but he was obdurate. He told me with emphasis, "No, I won't do it. I just can't work with Cook; he irritates me beyond endurance." Finally, I undertook the work of writing the lyrics, and actually got Cook to agree to have Bob Cole do the book... The Cannibal King was never wholly completed. Enough was finished, however, to enable Cook to negotiate a sale to a producer for a flat cash price that gave us several hundred dollars apiece. This was my first work with Cook; later, through the years, we wrote a number of songs in collaboration.

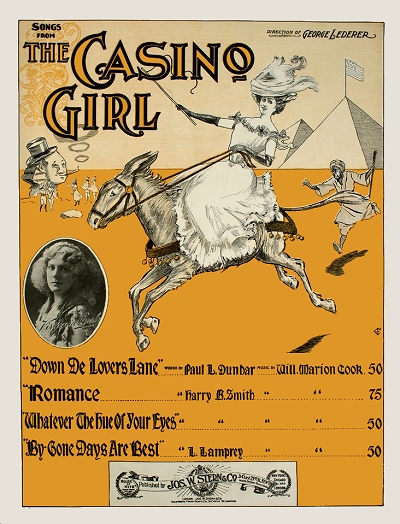

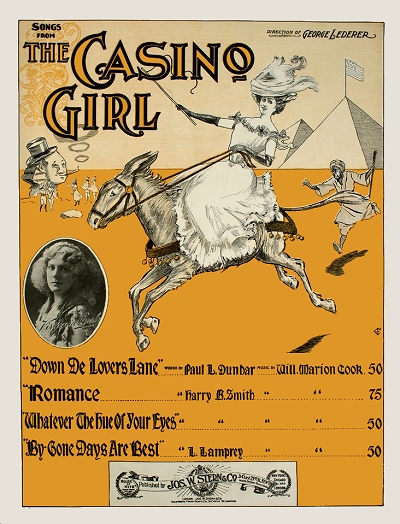

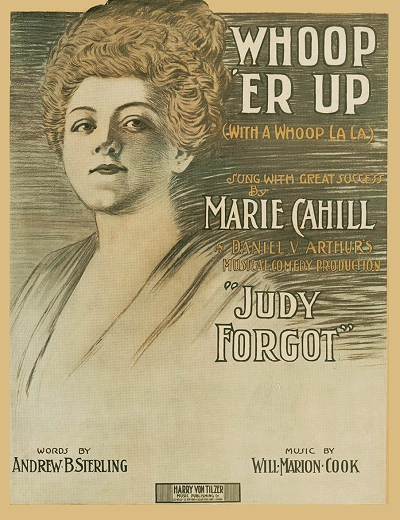

The Cannibal King opened in London in mid-1899 to mixed reviews, then in the United States. Through this work, and the growing reputation of Clorindy, Cook managed to garner growing respect in the musical world at large, but remained at odds with some of his peers, many of whom he clearly looked down upon for the role in perpetuating "coon songs" and lower forms of theater with base Negro dialects. He was engaged for another small set of songs with different lyricists that were interpolated into a 1900 production of The Casino Girl. There were some misfires over the next couple of years, and a few minor song hits penned with some of Will's allegedly reticent but tolerant peers, including Harry B. Smith and Richard McPherson (more widely known as Cecil Mack). With them he wrote The Little Gypsy Maid, interpolated into a production of The Wild Rose in 1902. Most of the pieces were published by Von Tilzer, Shapiro or Witmark, whose professional managers helped to interpolate songs by Cook and Mack into other productions of the period. This also put him into the field of vision of the successful team of Bert Williams and George Walker, as well as introduced a young lady singer named Abbie Mitchell. In reality, Abbie was his wife, the couple having married in 1899.

many of whom he clearly looked down upon for the role in perpetuating "coon songs" and lower forms of theater with base Negro dialects. He was engaged for another small set of songs with different lyricists that were interpolated into a 1900 production of The Casino Girl. There were some misfires over the next couple of years, and a few minor song hits penned with some of Will's allegedly reticent but tolerant peers, including Harry B. Smith and Richard McPherson (more widely known as Cecil Mack). With them he wrote The Little Gypsy Maid, interpolated into a production of The Wild Rose in 1902. Most of the pieces were published by Von Tilzer, Shapiro or Witmark, whose professional managers helped to interpolate songs by Cook and Mack into other productions of the period. This also put him into the field of vision of the successful team of Bert Williams and George Walker, as well as introduced a young lady singer named Abbie Mitchell. In reality, Abbie was his wife, the couple having married in 1899.

many of whom he clearly looked down upon for the role in perpetuating "coon songs" and lower forms of theater with base Negro dialects. He was engaged for another small set of songs with different lyricists that were interpolated into a 1900 production of The Casino Girl. There were some misfires over the next couple of years, and a few minor song hits penned with some of Will's allegedly reticent but tolerant peers, including Harry B. Smith and Richard McPherson (more widely known as Cecil Mack). With them he wrote The Little Gypsy Maid, interpolated into a production of The Wild Rose in 1902. Most of the pieces were published by Von Tilzer, Shapiro or Witmark, whose professional managers helped to interpolate songs by Cook and Mack into other productions of the period. This also put him into the field of vision of the successful team of Bert Williams and George Walker, as well as introduced a young lady singer named Abbie Mitchell. In reality, Abbie was his wife, the couple having married in 1899.

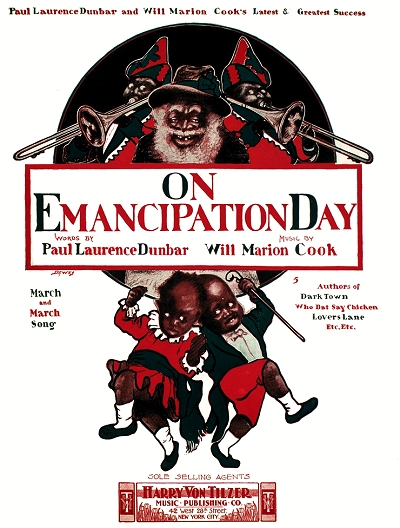

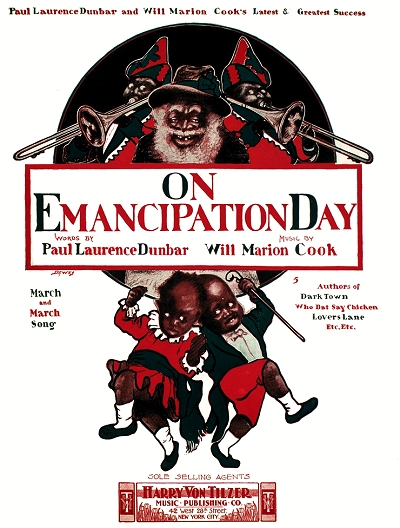

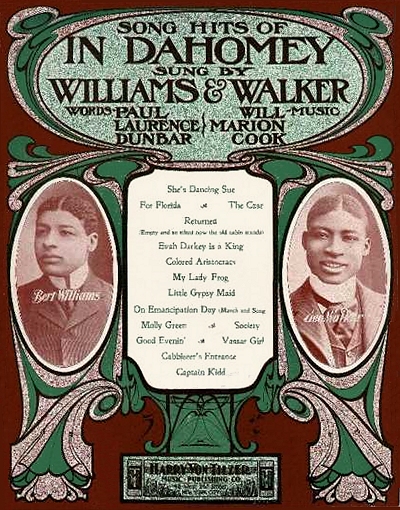

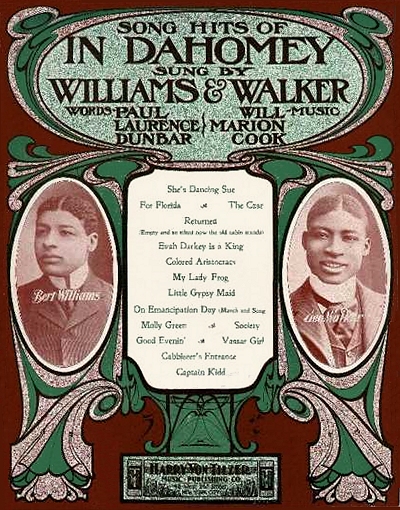

many of whom he clearly looked down upon for the role in perpetuating "coon songs" and lower forms of theater with base Negro dialects. He was engaged for another small set of songs with different lyricists that were interpolated into a 1900 production of The Casino Girl. There were some misfires over the next couple of years, and a few minor song hits penned with some of Will's allegedly reticent but tolerant peers, including Harry B. Smith and Richard McPherson (more widely known as Cecil Mack). With them he wrote The Little Gypsy Maid, interpolated into a production of The Wild Rose in 1902. Most of the pieces were published by Von Tilzer, Shapiro or Witmark, whose professional managers helped to interpolate songs by Cook and Mack into other productions of the period. This also put him into the field of vision of the successful team of Bert Williams and George Walker, as well as introduced a young lady singer named Abbie Mitchell. In reality, Abbie was his wife, the couple having married in 1899.Cook's first major success came in 1903 with In Dahomey. Written and copyrighted in 1902 with a book by Shepard Edmonds and lyrics once again by Dunbar, with Williams and Walker as the stars, it couldn't help but succeed with the best of black talent that New York had to offer. In Dahomey also overall has been viewed historically as the first black-written and produced music to rival similar white productions of the New York stage. The combination of operetta structure with ragtime music resonated with white audiences as well, and the production was regarded as substantial enough that it was the first major black-originated musical to be given an indoor stage on which to play. At that, one of the more popular pieces of the show was an interpolated number written by Alex Rogers, who was already an important part of Cook and Mack's world. Another piece written by Cook with scant lyrics by Dunbar was On Emancipation Day, essentially a cakewalk with lyrics added into the trio section. The show would ultimately play in New York, London, and on tour for the next four years. It also was the first major production to have the majority of its score published. However, it was issued by a British publisher, rather than one in New York, a situation which incensed Cook and set up a circumstance that would change the world of publishing for black composers and performers.

Gotham-Attucks and the Search for Recognition

Will's brother John, also a musician and composer by now, had come to New York as well, and in 1904 saw an opportunity to help out his older brother and perhaps make some money in the process. Given Will's uneven temperament and his tenuous relationship with publishers and producers, he and some of his peers were clearly not getting the best possible deal for royalties or buyouts, particularly for hit shows. So John formed his own publishing company in the heart of Tin Pan Alley at 42 West 28th Street, which was also the current address for Harry Von Tilzer's company, and very near Albert Von Tilzer's distribution firm. Over the next several months of 1904, John published songs that were all by Will, including three from his next production, The Southerners, with lyrics by Harry Smith as Richard Grant.

However, the perception of John Cook's company as a vanity label for his brother was correct, and he sought to change that by expanding the scope and the stable of composers associated with him. Among them was Cecil Mack (R.C. McPherson), who had managed to work successfully with Will. So in February of 1905 John incorporated his firm for $10,000 as Gotham Music, with Will as the primary director, McPherson as a partner (and the major financial contributor at the beginning), and club owner Barron D. Wilkins, who owned several black cabarets and bars in the Tenderloin district of New York, and also provided some solid financial backing and a presence the banks would be willing to work with. Among their first issues in their short life were two Bert Williams songs with lyrics by Earle C. Jones, as well as relabeled sheets of the songs from The Southerners. They added several more pieces, but in a haphazard fashion, with many of them lacking the quality found in the catalogs of other small publishers, including Shep Edmond's own Attucks insignia founded shortly before Cook's own company.

Among them was Cecil Mack (R.C. McPherson), who had managed to work successfully with Will. So in February of 1905 John incorporated his firm for $10,000 as Gotham Music, with Will as the primary director, McPherson as a partner (and the major financial contributor at the beginning), and club owner Barron D. Wilkins, who owned several black cabarets and bars in the Tenderloin district of New York, and also provided some solid financial backing and a presence the banks would be willing to work with. Among their first issues in their short life were two Bert Williams songs with lyrics by Earle C. Jones, as well as relabeled sheets of the songs from The Southerners. They added several more pieces, but in a haphazard fashion, with many of them lacking the quality found in the catalogs of other small publishers, including Shep Edmond's own Attucks insignia founded shortly before Cook's own company.

Among them was Cecil Mack (R.C. McPherson), who had managed to work successfully with Will. So in February of 1905 John incorporated his firm for $10,000 as Gotham Music, with Will as the primary director, McPherson as a partner (and the major financial contributor at the beginning), and club owner Barron D. Wilkins, who owned several black cabarets and bars in the Tenderloin district of New York, and also provided some solid financial backing and a presence the banks would be willing to work with. Among their first issues in their short life were two Bert Williams songs with lyrics by Earle C. Jones, as well as relabeled sheets of the songs from The Southerners. They added several more pieces, but in a haphazard fashion, with many of them lacking the quality found in the catalogs of other small publishers, including Shep Edmond's own Attucks insignia founded shortly before Cook's own company.

Among them was Cecil Mack (R.C. McPherson), who had managed to work successfully with Will. So in February of 1905 John incorporated his firm for $10,000 as Gotham Music, with Will as the primary director, McPherson as a partner (and the major financial contributor at the beginning), and club owner Barron D. Wilkins, who owned several black cabarets and bars in the Tenderloin district of New York, and also provided some solid financial backing and a presence the banks would be willing to work with. Among their first issues in their short life were two Bert Williams songs with lyrics by Earle C. Jones, as well as relabeled sheets of the songs from The Southerners. They added several more pieces, but in a haphazard fashion, with many of them lacking the quality found in the catalogs of other small publishers, including Shep Edmond's own Attucks insignia founded shortly before Cook's own company.Among the nearly-instant troubles faced by Gotham were challenges from other publishers about existing material that the new company allegedly had purloined or to which they did not have a proper claim. In April of 1905, that included the song with a potential hit status, Let's Play a Game of Soldiers, written by Joseph T. Quirk and David Rose while Quirk was allegedly in the employ of publisher Will Haskins. After Haskins reportedly passed on the song and parted ways with Quirk, the latter went directly to McPherson and his new company with the song, giving full disclosure of the circumstances, but noting that it had not been copyrighted. So after Gotham obtained legal copyright, Haskins had them enjoined so they could not issue the piece he had just passed on, and asked for $10,000 in damages. Ultimately Haskins, who had already taken out advertisements on the piece in the trades, did not get much of what he was looking for, but neither did Gotham as the song was only tepid seller with the public.

Less than four months in by the end of May, having already been dealt blows by court troubles and the lack of a clear hit to generate revenue, Gotham was looking to raise their profile a bit. They had good writers under contract, as did Attucks, but these writers also had contracts with theatrical companies who in turn were already set with Stern, Witmark, and other large firms. So when Shep Edmonds was looking to uncomplicate his life and turn a small profit on Attucks, and Gotham was looking for a profitable but reasonable property, it appears that Nobody and other select pieces were enticing enough for McPherson, Cook and company to go forward with a merger/acquisition. It was announced in the New York papers on May 28, 1905, that, "The Gotham Music Company and the Attucks Music Company have consolidated and shall hereafter operate under the firm name of the Gotham-Attucks Music Company." By late July the ink was dry and they were in business, as per several notices in the music trades. But for how long and to what end?

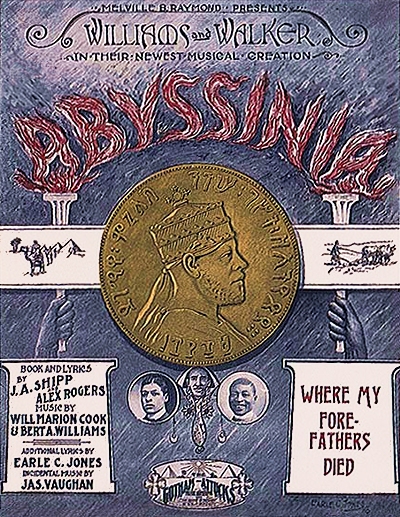

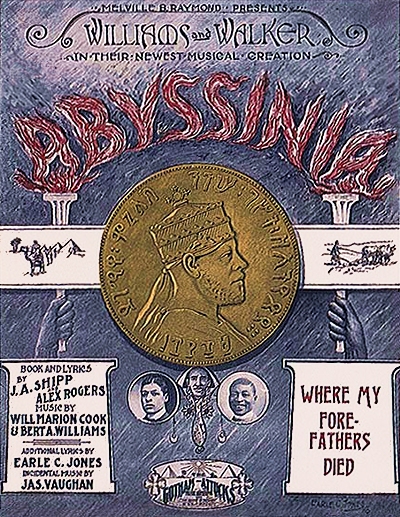

The 1905 New York State census revealed that Will Cook and Abbie Mitchell were residing in Manhattan with their daughter Marion (1900) and son William Mercer (1903), as well as Will's aunt Isabella Howard. Both of them were listed as musicians. He spent much of that year performing at the piano, and perhaps consulting with his new company, rather than writing. Late in the year, however, Will was busy once again, having written much of the music for his comic opera Abyssinia to a book and lyrics collectively by Bert Williams, Alex Rogers and Jesse Shipp. Debuting in the midst of the winter of 1906, initial reviews of Abyssinia were tepid, with the New York Morning Telegraph of February 21, 1906 insisting that it was "Far From a Hit," and "Devoid of the True Negro Spirit." Reviewer Irving Lewis, without overtly saying so, inferred that it was simply not black enough, or perhaps even racial enough:

Both of them were listed as musicians. He spent much of that year performing at the piano, and perhaps consulting with his new company, rather than writing. Late in the year, however, Will was busy once again, having written much of the music for his comic opera Abyssinia to a book and lyrics collectively by Bert Williams, Alex Rogers and Jesse Shipp. Debuting in the midst of the winter of 1906, initial reviews of Abyssinia were tepid, with the New York Morning Telegraph of February 21, 1906 insisting that it was "Far From a Hit," and "Devoid of the True Negro Spirit." Reviewer Irving Lewis, without overtly saying so, inferred that it was simply not black enough, or perhaps even racial enough:

Both of them were listed as musicians. He spent much of that year performing at the piano, and perhaps consulting with his new company, rather than writing. Late in the year, however, Will was busy once again, having written much of the music for his comic opera Abyssinia to a book and lyrics collectively by Bert Williams, Alex Rogers and Jesse Shipp. Debuting in the midst of the winter of 1906, initial reviews of Abyssinia were tepid, with the New York Morning Telegraph of February 21, 1906 insisting that it was "Far From a Hit," and "Devoid of the True Negro Spirit." Reviewer Irving Lewis, without overtly saying so, inferred that it was simply not black enough, or perhaps even racial enough:

Both of them were listed as musicians. He spent much of that year performing at the piano, and perhaps consulting with his new company, rather than writing. Late in the year, however, Will was busy once again, having written much of the music for his comic opera Abyssinia to a book and lyrics collectively by Bert Williams, Alex Rogers and Jesse Shipp. Debuting in the midst of the winter of 1906, initial reviews of Abyssinia were tepid, with the New York Morning Telegraph of February 21, 1906 insisting that it was "Far From a Hit," and "Devoid of the True Negro Spirit." Reviewer Irving Lewis, without overtly saying so, inferred that it was simply not black enough, or perhaps even racial enough:What a pity it is that colored folk cannot be the real thing? Why don't they give us darky songs and buck dancing and negro [sic] wit instead of trying to do what the white folks do? We don't go to the theatre to see darkies paint their faces or wear yellow wigs or display diamonds. We go to hear plantation melodies, witness negro dances and generally be entertained in negro [sic] style.

This applies to Williams & Walker and their company who opened with their new musical comedy "Abyssinia" at the Majestic Theatre last night. And all Darktown was there. Black men and yellow men, and negroes [sic] almost white! and one negro with red hair — quite a curio he was — and varnish-colored men and pickaninnies in kilts, and girls with shiny black faces and small woolly braids, and others with rouge on their cheeks and hair that did not look as if it grew on their heads — all were there...

"Abyssinia" really did not make a hit, far from it. It is not comparable with Williams & Walker's last piece. The comedy from beginning to end was written by colored men, it was staged by colored men. darkeys played it, a good-looking light-colored man, Will Marion Cook, directed the orchestra. And it seemed as if they had all said to each other and to themselves, "We'll iust show these white folks that we can do what they do, and do it as well." Instead of giving a genuine negro piece they gave a poor performance of a poor imitation of a white piece. It started out like grand opera and, indeed, before it was finished a section of Mendelssohn's Wedding March was played...

About a score of songs are introduced, none of them of any great merit. The features of the show were the dancing and [cake-]walking of George Walker, the singing and dancing of Aida Overton Walker, and Bert Williams' all around work... He was the only real hit in "Abyssinia." and he did not have anywhere near enough to do... The audience hated to see him leave the stage.

Other papers were a little more generous, but clearly this was not the reception that Cook had hoped Abyssinia would warrant. As a matter of course, black journalist named Carle Browne Cooke (not a relation) took issue with the review by Mr. Lewis, firing off a retort that appeared in the Telegram the next day on February 22:

I do not attempt to indict you for expressing your impressions on the very best product of entertainment embodied in the so-labeled "musical comedy" (which is really, in justice to its able producers, a modern negro-comic opera), "Abyssinia." But the play possesses every element requisite of comic opera classification, even though its whole environment is quite foreign to average patrons of high-class amusements offered by the several colored producers in this country...

You exclaimed at the offset: "What a pity it is that colored folk cannot be the real thing!" Now, the colored people are the real things; so are the Caucasians, who have proven to lovers of real drama that there are several grades of the real thing, ranging in reasonable succession from the lowest to the highest in standard...

From your denouncement I am of the opinion that you have but a surface knowledge of the Abyssinian people and their country, etc. ...you say it did not make a real hit. I refute this, and will remind you that you said the music started off like grand opera. It surely did, because Prof. Will Marion Cook is a master composer and has developed negro music up to a standard of quality superior to the average comic-opera score. It is true a few numbers are reminiscent, but this is true of the music of all our later day composers.

The show became popular enough that they took it to Washington, DC, in late April and early May, where it was seen by President Theodore Roosevelt and Civil Rights activist Booker T. Washington. However, Will and Abbie had sailed for Europe in late March, and he apparently did not make it back to the US in time to conduct for these performances. In late 1905 and into 1906, Cook had presented his Tennessee Students (originally the Memphis Students) ensemble act in New York. In late 1906 into 1907 they repeated the act in Europe, then in the US at the Victoria Roof venue, followed by a short run at Hammerstein's. The show starred Ernest Hogan as well as Abbie Mitchell. Cook and his wife had worked together for some time, and even though it was not widely publicized for many years, the word was out that the two had been married for several years. As to her particular level of talent, an early 1907 review of Tennessee Students helped to give a measure of depth to it in a short description:

In late 1906 into 1907 they repeated the act in Europe, then in the US at the Victoria Roof venue, followed by a short run at Hammerstein's. The show starred Ernest Hogan as well as Abbie Mitchell. Cook and his wife had worked together for some time, and even though it was not widely publicized for many years, the word was out that the two had been married for several years. As to her particular level of talent, an early 1907 review of Tennessee Students helped to give a measure of depth to it in a short description:

In late 1906 into 1907 they repeated the act in Europe, then in the US at the Victoria Roof venue, followed by a short run at Hammerstein's. The show starred Ernest Hogan as well as Abbie Mitchell. Cook and his wife had worked together for some time, and even though it was not widely publicized for many years, the word was out that the two had been married for several years. As to her particular level of talent, an early 1907 review of Tennessee Students helped to give a measure of depth to it in a short description:

In late 1906 into 1907 they repeated the act in Europe, then in the US at the Victoria Roof venue, followed by a short run at Hammerstein's. The show starred Ernest Hogan as well as Abbie Mitchell. Cook and his wife had worked together for some time, and even though it was not widely publicized for many years, the word was out that the two had been married for several years. As to her particular level of talent, an early 1907 review of Tennessee Students helped to give a measure of depth to it in a short description:Abbie Mitchell, who heads the act, uses good judgment throughout in confining herself to the simple ballads. Hers is a voice of evident training, but she avoids the common mistake of seeking to display its technical brilliancy at the expense of simplicity.

The increasingly frustrated Cook, who at times made quite clear his view of poor race relations within the publishing business, may have felt targeted when at the end of January Gotham-Attucks faced yet another legal challenge. The firm of May & Harris, representing small publisher Morris Music, put legal rights to the moderate hit song He's a Cousin of Mine into receivership, claiming that they had sold a share of the piece to Gotham-Attucks, rather than an outright sale. The negative publicity did not help, as they kept referring Gotham-Attucks as a "colored" firm or one run by "colored managers." Then things escalated for Cook personally in February of 1907 when he was fined $150 by the manager of Tennessee Students when the show went to Boston, but his wife Abbie instead sailed for the Wintergarten in Berlin, Germany, as she had allegedly not been contractually obligated to take the tour. The indignant and obstinate Cook not only vowed to the press that he would get back the $150, but that he would ask for an extra punitive $5,000 "as a balm."

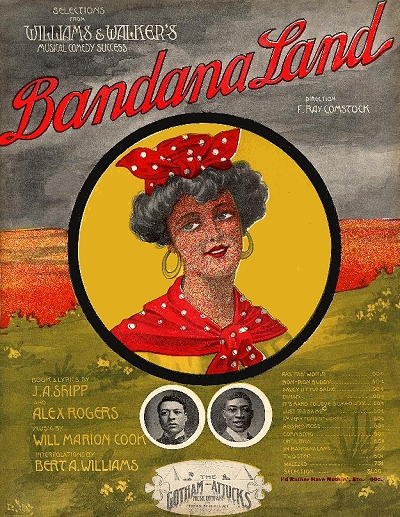

In the end, Cook got his $150, and the action against Gotham-Attucks was decided in their favor for He's a Cousin of Mine, but both of these fights required energy and money, which resulted in little net gain. Cook, Shipp, Rogers and Williams came out with another successful musical later in the year, Bandanna Land. However, another continuing challenge in the company's efforts to remain vital came from established practices and alliances between theatrical producers and key publishers of Tin Pan Alley, which inhibited them from acquiring or retaining material. Cecil Mack and James Reese Europe wrote a score for Gus Hill in 1907 titled The Black Politician, starring the increasingly favored comedian Sherman H. Dudley. This was the first complete score that Mack had been involved with, and presented a good opportunity for Europe, who would soon have a prestigious command of sorts over the black musicians of New York.

However, Mack's own firm was not able to get publication rights for his own work, as Hill had engaged Will Rossiter, "The Chicago Publisher," to take on at least five of the pieces, likely in exchange for some financial assistance with staging the production.

|

Even with their collective involvement, Williams, Smith, and even the difficult Cook, had standing contractual arrangements with other publishers and quotas to fill, so they could not always supply good content for their own concern. Other black composers who were friends and associates of the directors ended up having nothing to offer Mack and Cook's company, including Irving Jones, Bob Cole, Ernest Hogan, Al Johns, and their founding father, Shepard Edmonds. The result was an average of ten pieces per year issued by Gotham-Attucks, in contrast to the 150 to 2,000 publications put out annually by other Tin Pan Alley firms. Only the stalwart E.T. Paull was issuing less, but his reputation and colorful covers kept his firm profitable. The larger firms were also more enticing to black writers, since they had the resources and personnel to plug their works (although often by masking the race or gender of their writers) both to the public and to vaudeville and theatrical performers. The lack of profitability even made advertisements in trade papers or general newspapers difficult, and they often had to depend on plugs and announcements, as well as their promotional material on the back covers of Gotham-Attucks sheets.

While Bandanna Land offered some hope through minor hits that Mack was able to retain, in addition to an interpolation of Nobody for a second round of sales, the only notable piece from the production was the comically salacious Mack/Smith number, You're in the Right Church But the Wrong Pew. This helped to make 1908 a slightly better year, and they even felt confident enough to move from 28th street to a location closer to the major theaters, 136 West 37th Street. Another promotional vehicle was the formation of The Frogs (pictured left), founded by Williams and Walker, and made up of the leading black composers and performers of New York during that year, although with the conspicuous absence of independently-minded Will Cook. Mack was the first secretary of the organization, headed by George Walker and John Rosamond Johnson. While not directly beneficial to Gotham-Attucks, just the mention of the composers' names in the reports of various functions they held or appeared at was a peripheral form of publicity. They soon expanded the esteemed group to include professionals from other high-profile fields as well. Still, it was not quite enough to be of much help to the struggling firm.

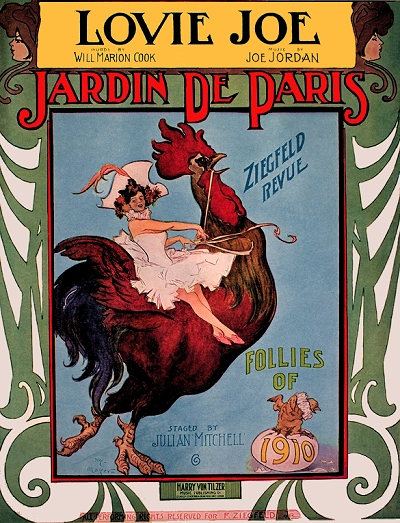

In spite of the growing success of That's Why They Call Me Shine, it was clear that Gotham-Attucks could not survive on the income from just a few works. Even its most ardent champions were going elsewhere in order to make a respectable amount from their newest compositions, or at least see the distributed more effectively around the country. Smith and Williams were among the more evident defectors, and along with Smith at times was the company's director, Cecil Mack, who had to admit to the trouble in his firm. Regardless of the roles that Will and John Cook played in getting Gotham-Attucks launched, even Will had his latest 1910 hit, Lovie Joe, published by Harry Von Tilzer. These firms could count on volume, knowing that the occasional hit would counter any flat sales by other pieces, but Gotham-Attucks simply did not have that advantage.

Regardless of the roles that Will and John Cook played in getting Gotham-Attucks launched, even Will had his latest 1910 hit, Lovie Joe, published by Harry Von Tilzer. These firms could count on volume, knowing that the occasional hit would counter any flat sales by other pieces, but Gotham-Attucks simply did not have that advantage.

Regardless of the roles that Will and John Cook played in getting Gotham-Attucks launched, even Will had his latest 1910 hit, Lovie Joe, published by Harry Von Tilzer. These firms could count on volume, knowing that the occasional hit would counter any flat sales by other pieces, but Gotham-Attucks simply did not have that advantage.

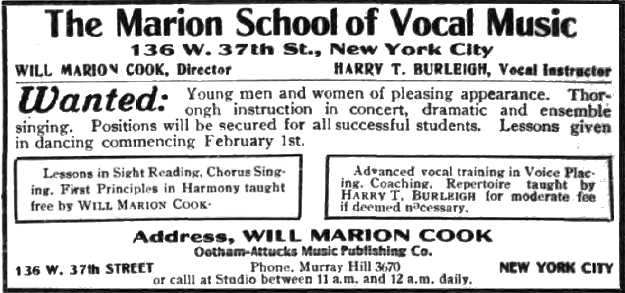

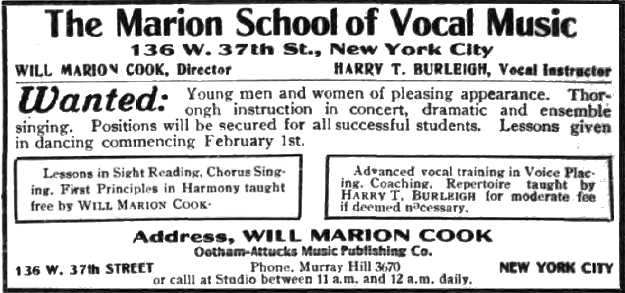

Regardless of the roles that Will and John Cook played in getting Gotham-Attucks launched, even Will had his latest 1910 hit, Lovie Joe, published by Harry Von Tilzer. These firms could count on volume, knowing that the occasional hit would counter any flat sales by other pieces, but Gotham-Attucks simply did not have that advantage.Will Cook was looking to supplement his income, so he used the firm as a base for a small school for students interested in learning vocal skills and drama. Cook was assisted by one of his few close friends who had encouraged him in the beginning, Harry Burleigh, who was the vocal instructor. They placed several advertisements in the black-oriented New York Age in late 1909 and early 1910, using the Gotham-Attucks building as the address. Mack also reached out beyond his own community, soliciting songs from white writers as well, including the lesser known at that time L. Wolfe Gilbert. But without the necessary resources to hire song pluggers or place copious newspaper advertisements, they just could not get the necessary traction to turn the average piece into even a moderate seller.

The 1910 enumeration showed McPherson lodging not all that far from his office, and listed as a music publisher, albeit with more than a half-decade trimmed from his actual age. Will Marion Cook was now divorced, listed as a composer of music, and lodging with orchestra musician Daniel E. Murray He would work with Abbie on selected occasions over the next few years. She kept the children, although they were as much in the care of her parents as herself, as she had not yet given up the stage.

Cook was largely disengaged from Gotham-Attucks by 1911, but still very much in the news, and as obstinate as he had ever been, at times rightfully, concerning the view of him as a talented "colored" composer and musician. This attitude created a stir in November of 1910 when he sent a letter to the dramatic editor of the New York Age, reprinted an commented on in their February 9, 1911 issue, charging that colored composers and performers were being "discriminated against by several white music publishers. It also underscored his impending separation from his own publishing house.

A recent experience with a music publishing concern inspires me to comment on the treatment colored composers and artists received from some of these firms. As you now, for the past year all my songs have been published by the Harry Von Tilzer Publishing Company. Knowing this to be my headquarters many well-known colored writers, actors and singers have called on me at the Von Tilzer offices to consult about material either for use on the stage or in regard to having songs published [albeit evidently not by Gotham-Attucks].

The professional manager of the Von Tilzer Company, Max Winslow, after expressing disapproval of many of these visits by sour looks and evidences of lack of courtesy to my visitors, finally blankly informed me recently "that entirely too many spades come in the office."

Inasmuch as music of the day is to a great degree popularized by the colored performer and café singer, and inasmuch as the majority of music firms cater to the colored actor and singer when they have new songs, I feel that the color prejudice of Mr. Winslow should be widely known. I would suggest that since our singing of songs helps to popularize and increase the sale, that we seek those firms where our presence is not only welcomed but eagerly sought... I have often noticed and commented on the courtesy shown them at Remicks, Witmark's, Ted Snyders and others...

The editor generously noted that "Will Marion Cook is said to be somewhat erratic in his method of transacting business at times... yet his veracity has never been questioned." The issue was a legitimate one, and indeed, underscored the very reason that Gotham-Attucks had been formed in the first place. Yet in spite of their intent, the larger white-run firms simply dominated the music industry in New York. Prejudice still obviously existed, even progressive in New York City, but it was usually at the individual level rather than corporate. To that end, younger brother Will Von Tilzer responded to the charge in the February 23, 1911, issue of the New York Age, with no love lost for Cook, although voiced in a diplomatic fashion:

The writer wishes to state that the whole article is not only an injustice to the Harry Von Tilzer Music Publishing Company, but to all the colored writers and performers. The man who was instrumental in having the article printed to a great extent, his present opportunities to a member of the Barry Von Tilzer Music Publishing Company. He found plenty of encouragement here during the twelve months that this company entered to his needs.

We believe, as a paper catering to the colored people, you wish your readers to know the truth, and do not want to have them labor under the impression that has been conveyed to them by a man who is allowing personal prejudice to interfere with his better judgment...

If you will consult the representative performers and writers of your race, I believe you will easily be able to convince yourself that they have never lacked courteous treatment In the establishment of Harry Von Tilzer.

We are writing you this letter not because we are soliciting favors from anyone, but because, as stated above, we believe that there has been an injustice done your paper.

The editor lauded the efforts of Will Von Tilzer, yet noted that there was no denial of Max Winslow's role in the incident. This likely added a little bit of poison to the reputation of Cook among the major publishers, underscoring the very need for a firm like Gotham-Attucks, but his reputation as a musician and composer trumped the other concerns, so he rarely lacked for a publisher willing to take on his work. To that end, he was done with the experiment, and his defection, along with Smith, Williams, and others, imploded the efficacy of their firm.

McPherson, more or less the last surviving member of Gotham-Attucks, finally threw in the towel in mid-1911. Mack held a fire sale of the company's major copyrights, most of which went to a company he had done with business with for a decade, Joseph Stern. Remaining properties were later purchased by the Robbins-Engel firm. Both companies reissued songs like Shine and Nobody separately, but most of the rest of them in folios, generating at least minimum income, albeit not for their originators. Surprisingly, Mack and Wilkins did not simply dispose of the firm, but sold off the name and the office space to another investor looking for an existing property. In hindsight, it turned out to be an unfortunate move and created a less than respectable end to a firm that had been founded with good intentions and optimism just six years prior.

Earning a Place in Music History

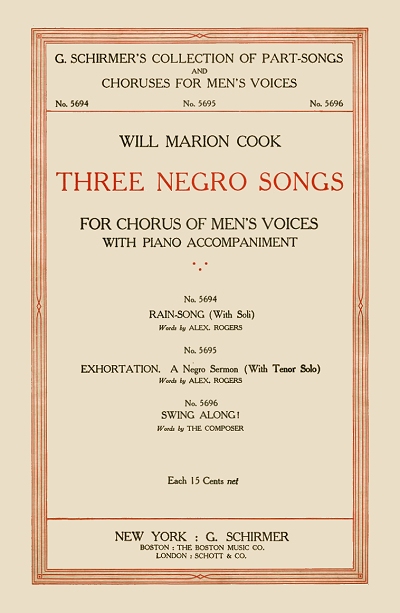

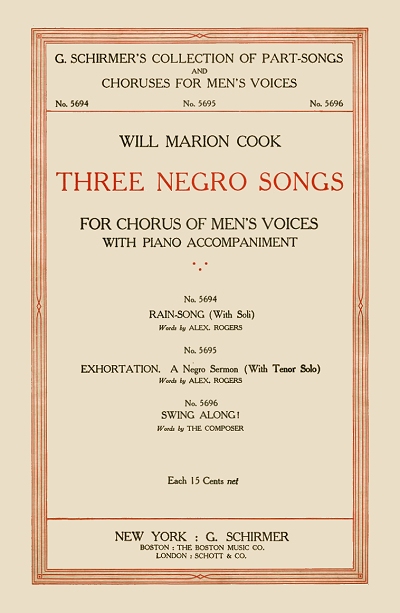

It was clear by 1911 that Cook had already distanced himself from Gotham-Attucks, the company founded in part due to his personal necessity, even though one additional copyright under the probable pseudonym of Barney Barber, written with Mack, was issued that spring. On May 2, 1912, James Reese Europe presided over a concert at Carnegie Hall that was a presentation of Cook's music with the Clef Club Orchestra. In fact, Europe insisted on Cook playing violin with the group during the concert, even though it was known he had all but abandoned the instrument nearly two decades prior. Cook agreed to do so as an anonymous member of the violin section. In particular, his landmark works Swing Along and Rain Song were enthusiastically received by the audiences. Europe had little choice but to single him out from his place in the orchestra so the audience would know who was responsible for the moment, causing him to weep, having been overcome with emotion at the acclaim. Will Marion Cook had finally arrived to a point of recognition that he had hoped for, and in this case deserved. Swing Along, Rain and one other companion piece, Exhortation, were published by G. Schirmer as a set, and saw wide circulation over subsequent decades, particularly to choral groups and universities. To cap the triumph off of this part of his life, Cook was named one of "100 Distinguished Freedmen" in 1913 as part of the National Emancipation Exposition held in New York City.

On May 2, 1912, James Reese Europe presided over a concert at Carnegie Hall that was a presentation of Cook's music with the Clef Club Orchestra. In fact, Europe insisted on Cook playing violin with the group during the concert, even though it was known he had all but abandoned the instrument nearly two decades prior. Cook agreed to do so as an anonymous member of the violin section. In particular, his landmark works Swing Along and Rain Song were enthusiastically received by the audiences. Europe had little choice but to single him out from his place in the orchestra so the audience would know who was responsible for the moment, causing him to weep, having been overcome with emotion at the acclaim. Will Marion Cook had finally arrived to a point of recognition that he had hoped for, and in this case deserved. Swing Along, Rain and one other companion piece, Exhortation, were published by G. Schirmer as a set, and saw wide circulation over subsequent decades, particularly to choral groups and universities. To cap the triumph off of this part of his life, Cook was named one of "100 Distinguished Freedmen" in 1913 as part of the National Emancipation Exposition held in New York City.

On May 2, 1912, James Reese Europe presided over a concert at Carnegie Hall that was a presentation of Cook's music with the Clef Club Orchestra. In fact, Europe insisted on Cook playing violin with the group during the concert, even though it was known he had all but abandoned the instrument nearly two decades prior. Cook agreed to do so as an anonymous member of the violin section. In particular, his landmark works Swing Along and Rain Song were enthusiastically received by the audiences. Europe had little choice but to single him out from his place in the orchestra so the audience would know who was responsible for the moment, causing him to weep, having been overcome with emotion at the acclaim. Will Marion Cook had finally arrived to a point of recognition that he had hoped for, and in this case deserved. Swing Along, Rain and one other companion piece, Exhortation, were published by G. Schirmer as a set, and saw wide circulation over subsequent decades, particularly to choral groups and universities. To cap the triumph off of this part of his life, Cook was named one of "100 Distinguished Freedmen" in 1913 as part of the National Emancipation Exposition held in New York City.

On May 2, 1912, James Reese Europe presided over a concert at Carnegie Hall that was a presentation of Cook's music with the Clef Club Orchestra. In fact, Europe insisted on Cook playing violin with the group during the concert, even though it was known he had all but abandoned the instrument nearly two decades prior. Cook agreed to do so as an anonymous member of the violin section. In particular, his landmark works Swing Along and Rain Song were enthusiastically received by the audiences. Europe had little choice but to single him out from his place in the orchestra so the audience would know who was responsible for the moment, causing him to weep, having been overcome with emotion at the acclaim. Will Marion Cook had finally arrived to a point of recognition that he had hoped for, and in this case deserved. Swing Along, Rain and one other companion piece, Exhortation, were published by G. Schirmer as a set, and saw wide circulation over subsequent decades, particularly to choral groups and universities. To cap the triumph off of this part of his life, Cook was named one of "100 Distinguished Freedmen" in 1913 as part of the National Emancipation Exposition held in New York City.Will was finally allowed joined the Clef Club as a chorus master and arranger, although his relationship with some of the members, as well as the directors, would be a thorny one at best. Still, they could not deny the power of his music or his other abilities, so an uneasy alliance existed for some time. By 1914, however, Europe himself would leave the Clef Club for other pursuits, including working for the dancing time of Vernon and Irene Castle. Will continued to write and rework shows, but not to the same acclaim he had enjoyed previously. Music styles were progressing from ragtime into jazz, and Cook's 1913 show The Traitor ad his 1914 revival of The Cannibal King were not so progressive for contemporary tastes. In an effort to adapt, he followed the lead of producer Lester Walton who teamed Will with James Reese Europe, author Henry Troy, and lyricist Henry Creamer, to write the surprisingly backwards-thinking Negro-centric show Darkeydom. The production met a mixed reception in Washington, DC, and an even icier one in New York. In spite of the current nostalgic revival of the Cakewalk in 1915, an old-time show that bordered on "coon song" paradigms no longer had any shelf life, and it closed fairly quickly. Even though he had been composing syncopated tunes for some time, it was not until 1914 that Cook had issued any syncopated instrumentals, starting with Cruel Papa.

Many of the younger New York musicians, some of them Cooks current and former colleagues, enlisted for the war effort in 1917. Lucky Roberts, Willie "The Lion" Smith and James Europe ended up as part of the 369th U.S. Infantry "Hell Fighters," soon forming a legendary band from that unit which took France by storm in late 1918. Europe would go on to his own measure of fame after World War I, only to have his life cut short during an altercation with his drummer in 1919. In the absence of Europe and other key black musicians during the war, Cook, too old to serve, and having not written any successful shows since 1910, formed his New York Syncopated Orchestra out of some of the remains of the Clef Club, in addition to recruiting a choir. They spent part of 1918 and 1919 touring the United States. Notable for this less-than-profitable tour was the usually high-standard oriented Cook hiring as yet unknown clarinetist Sidney Bechet in Chicago to play with the group, even though Bechet was not much of a music reader. It was more likely for Sidney's jazz acumen than any other reason.

Facing stiff competition from a number of smaller and more lively jazz bands, not the least of them the white Original Dixieland Jazz Band formed by Dominic LaRocca and Larry Shield, Cook endeavored to go to England in the latter half of 1919 to see if he could turn a profit there.

However, the ODJB beat him to the punch, having played in London for some months by that time. Retooled as the Southern Syncopated Orchestra, Cook's group sailed for Liverpool in January of 1920. With Bechet at the forefront and square in the eyes of the reviewers, the group eventually managed an audience with King George V at Buckingham Palace in August of 1920. In spite of the attention, it was hard for the unwieldy group of fifteen to get standing gigs and turn a profit. Cook briefly returned to the United States to reorganize the SSO, then returned for more playing work in England, France and Germany from the fall of 1920 into 1921. The orchestra eventually broke up and Cook plus a few others returned to the United States in mid-1921. Bechet, now leaning towards soprano saxophone as his signature instrument, stayed behind in Europe for many years with some of the other orchestra members, many doing quite well for themselves in an environment more receptive to Negro musicians.

|

In the early 1920s, Cook worked now more as a conductor and arranger than as a composer. He also acted as a mentor for many young black composers, not the least of them being Edward "Duke" Ellington, who always held him in high regard in spite of Cook's continuing anger management issues. He also eventually provided support for some white talent as well, including a young Harold Arlen, a pianist who would eventually have a fine career in composition as well, writing, among other works, Over the Rainbow in 1939. In 1923, possibly at the request of his long-time friend Cecil Mack, Cook was engaged for a while to conduct the orchestra for the Washington, DC, tryout run of Runnin' Wild, composed by Mack and Harlem stride pianist James P. Johnson. This show included the hits Old Fashioned Love and The Charleston, giving Will direct contact with current music trends of that time.

Either passed over or disinterested in 1914 when the organization was first formed, Cook was finally admitted as a member of ASCAP in 1924, providing him at least some measure of legal protection and royalty income for the performance of his works, which were still popular in some quarters. Cook's last major piece was the folk opera Saint Louis 'Ooman written with his son Mercer, but it was never produced. (Mercer, who was a language studies professor at Howard University where his grandfather had excelled, later moved to Haiti, and would eventually become a US Ambassador to Niger, as well as a historian in Negro studies.) The lone piece that emerged from that effort into printed form was a reworking of the Negro spiritual Troubled in Mind. One additional song, albeit an important one, was I'm Coming Virginia, to which Will provided lyrics to Donald Heywood's music in 1927. It would gain further recognition as part of clarinetist Benny Goodman's historic Carnegie Hall concert in January of 1938.

The lone piece that emerged from that effort into printed form was a reworking of the Negro spiritual Troubled in Mind. One additional song, albeit an important one, was I'm Coming Virginia, to which Will provided lyrics to Donald Heywood's music in 1927. It would gain further recognition as part of clarinetist Benny Goodman's historic Carnegie Hall concert in January of 1938.

The lone piece that emerged from that effort into printed form was a reworking of the Negro spiritual Troubled in Mind. One additional song, albeit an important one, was I'm Coming Virginia, to which Will provided lyrics to Donald Heywood's music in 1927. It would gain further recognition as part of clarinetist Benny Goodman's historic Carnegie Hall concert in January of 1938.

The lone piece that emerged from that effort into printed form was a reworking of the Negro spiritual Troubled in Mind. One additional song, albeit an important one, was I'm Coming Virginia, to which Will provided lyrics to Donald Heywood's music in 1927. It would gain further recognition as part of clarinetist Benny Goodman's historic Carnegie Hall concert in January of 1938.Cook continued conducting, and in fact made the news briefly once again in 1929 concerning some controversy between him and the Musicians Union Local 802. He was fronting his own production of his recently assembled Swing Along show in April of 1929 when the management found that Cook did not have a current union card. It was reported in the New York Age that Cook was then prohibited from conducting his own show. Having never seen the necessity of being a Union member (discounting his involvement with the Clef Club of the prior decade), Cook had not yet joined one. His assistant, Will Vodery, arranged for the acquisition of a membership and a card, and all was restored. In their April 20 edition, The New York Age, noting the resolution, deftly summed the situation up, stating that, "In conjunction with Will Vodery, by unselfish and wise cooperation, a monument of musical strength could be constructed to place the colored musician in the forefront from which he is receding stubbornly but surely.

And so it was during the Great Depression that Will Marion Cook, well past his prime but still highly regarded for his work, more or less slowly but stubbornly receded into the background. He was called on occasionally for events honoring black musicians of days past, but had virtually no presence in radio or other current media of the 1930s except for occasional recordings of his works. He suffered from cancer during his last years, passing on in New York City in 1944 at age 75. Since Cook's death, his legacy has accurately but positively been captured in a number of books, as well as presentations and revivals of his important stage shows, and even new recordings of some of his notable serious songs.

Selected Known Compositions

Selected Known Compositions