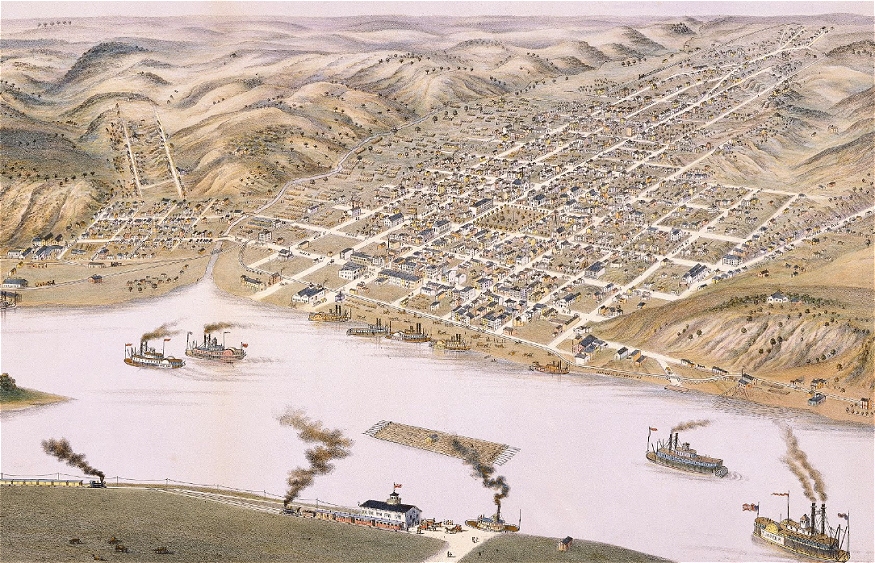

Cliff Edwards was reportedly, by his own admission, born in Hannibal, Missouri, a bucolic place on the Mississippi River long associated with Samuel Clemens, better known as author Mark Twain. He also reported his parents to be railroad worker (possibly also a fisherman) Edward Edwards and his wife Nellie Farnus. Even though Edwards listed this town on several documents throughout his life, including his 1917 and 1942 draft records, there are issues with verifying this location.

Even Cliff himself was quoted in 1940 to have recollected "vaguely" that he was born in the "vicinity of Hannibal," and that perhaps even the year and date of birth might also be in question. As he was born "on a houseboat at the base of Church Street" [possibly a partial myth], there is some possibility that his father was Edward E. Edwards of Quincy, Illinois, just a few miles up and across the Mississippi from Hannibal. However, that is also difficult to verify. Hannibal city directories for the first decade of 20th century reveal nobody with any of the family names living there, nor were there any matching Edwards, other than the previously mentioned resident of Quincy, that also suggested any connection with the town. In 1909 the majority of Edwardses in town were listed as colored, further narrowing the field. So Clifton's own recollection, of which there is little reason to doubt beyond its romantic notion, as well as those allegedly made by other citizens in that northeastern Missouri city, can be taken with a grain of salt, considering the clear lack of forensic evidence connecting the two.

|

Cliff's father became too ill to work in the early 1900s, so his son took to working as a newspaper butcher, perhaps even before he was ten, in order to support his mother and himself. He sang while selling the papers in order to draw more attention to the business. Then, reportedly as early as age ten (and the lack of child welfare laws at that time make this a possibility), Cliff went to work for the Roberts, Johnson and Rand Shoe Company on Collier between 7th and 8th Streets in Hannibal. During his years there it has been said, although specific sources are fuzzy, that he sang as he worked, entertaining nearby workers. At age fourteen or thereabouts, young Mr. Edwards tired of newspapers and shoe leather, and left Hannibal to pursue a different dream - one in which he was a musical star.

Cliff claims that he left Hannibal around 1909 or 1910, moving south down the river to Saint Louis, Missouri. He later recalled having been there in 1904 with his mother, visiting the Lewis and Clark Exposition also known as the World's Fair. Edwards was not readily located in the 1910 census anywhere in the United States, but as he was living as a transient at that time, and a minor one at that, it is not unlikely that he was skipped for that record. Using his singing talents, Cliff found some work in this musical town singing in saloons and theaters for tossed change. It was at one of those theaters that he met the manager of a number of such venues in Saint Louis, Lillian Crenshaw McIntyre. (She and her husband Edwin were listed in the 1910 census in Saint Louis as music teachers, so this is plausible.) Being a vocal coach herself, she worked with Cliff and hired him to sing to illustrated popular ragtime songs between acts in the vaudeville theaters or between film shorts in movie venues. In most cases, such theaters were provided these slides by the song publishers, as well as a supply of sheet music to sell in the lobby after the show. This required a measure of musical salesmanship that the lad evidently possessed. As he could not read music, he had to learn the tunes by rote from Lillian or some other musician.

As a piano or pianist were not always available, Cliff took it upon himself to learn a portable musical instrument that he could always have with him. His choice was driven more by economics than anything, as the ukulele, commonly known then as the soprano guitar, was the least expensive instrument in the store. Once he learned the proper tuning, Cliff taught himself the instrument, taking to it quickly and naturally. Mrs. McIntyre further encouraged him by giving him some stage time in her vaudeville theaters. He even traveled with a carnival for a while, touring the Midwest, then graduated to the Midwest vaudeville circuits. When he was unable to find other work, Cliff waited tables or worked lunch counters, painted rail cars, sold magazine subscriptions, and tried to find any playing gig he could in the evenings. By the time of the first World War I draft on June 5, 1917, just short of his 22nd birthday, Cliff was established in Chicago, Illinois, working for entrepreneur Ted Snow as a theatrical entertainer. Three months after that, on September 5, 1917, Clifton Avon Edwards was married in Chicago to 16-year-old Gertrude Rynholm Benson.

At some point in 1917 he started working at the Arsonia Café, located at 1652 West Madison, as an entertainer. (Some sources have referred to it as the Ansonia, but Chicago newspapers and directories of the time confirm the spelling as Arsonia.) This venue was known to have featured some of the bigger entertainers of that era when they passed through Chicago, albeit the white ones. These included Blossom Seeley and Gilda Gray among others. Between the floor shows, Edwards would go from table to table with a hat playing a tune or two on his uke, and hopefully collecting a tip for his effort. He later recalled that the more a patron had imbibed that evening, the bigger the tip would be.

and hopefully collecting a tip for his effort. He later recalled that the more a patron had imbibed that evening, the bigger the tip would be.

and hopefully collecting a tip for his effort. He later recalled that the more a patron had imbibed that evening, the bigger the tip would be.

and hopefully collecting a tip for his effort. He later recalled that the more a patron had imbibed that evening, the bigger the tip would be.Reports on how he got his famous nickname vary a bit, including Edwards sometimes claiming he just thought it up. Legend has it that a waiter named Spot, who was perhaps of Russian extraction, simply could not or would not remember the name of Cliff or other entertainers, so gave them his own names. For Cliff, he just called the singer "Ike," and others soon followed. Since Edwards was quickly becoming associated with his ukulele, he simply gave in to this trend and called himself Ukulele Ike. At times in history it has been shown spelled as Ukelele Ike in advertising, but the former is the correct spelling of the instrument and his title. (A personal side note from the author: This same thing happened to me while I was working in a pizza place in Durango, Colorado, where a regular started calling me "Perfessor" Bill, which also quickly stuck. Since so many people instantly remembered it, I kept it for good or bad. Thus, this part of Cliff's story is highly probable as I have had the same experience.)

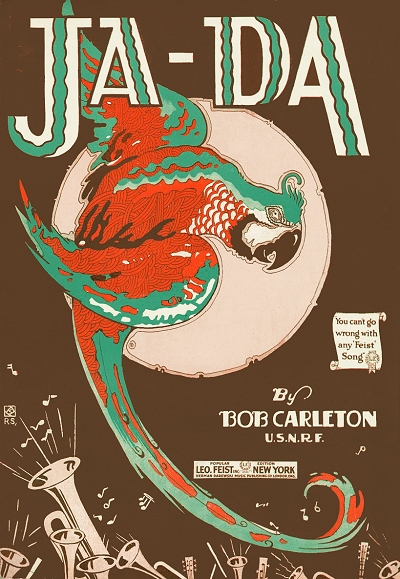

The first song of some level of fame that Cliff was involved with was Ja-Da, composed in 1918 by Bob Carleton of the United States Navy Relief Force, who was also a pianist at the Arsonia and other Chicago clubs. A very simple tune with a largely nonsensical lyric, Carleton first had Edwards sing it, and it became very popular around Chicago, then almost immediately around the country. Among its more interesting traits, it was published by Leo Feist in New York, and was one of very few pieces that was released in the long-standing "large format" size of 11" x 14", the war-time paper saving size of 5" x 7", and the new standard size adopted in 1918 of 9" x 12". It is unclear if the main lyric, "Ja-da, ja-da, ja-da ja-da jing jing jing," was inspired by or actually inspired the early scat singing style that Cliff would take on in his performance style, but it remains one of the first printed examples of vocal scat. In spite of his Chicago connection to the tune, which some have suggested he co-wrote, Edwards would not record it for more nearly four decades, so missed out on one potential hit.

In the middle of 1918 Cliff became associated with stuttering comedian and singer Joe Frisco, who while a touring vaudevillian was based in New York City. There is scant evidence that Cliff appeared with him in New York at the Palace, playing drums instead of ukulele, as Cliff and others took the stage in dancing and comic routines. As Joe was also part of the Ziegfeld Follies of 1918, there are some historians who believe that Cliff may have backed him in this star-studded show as well, but newspaper mentions with Edwards' name in them were not found in multiple New York and entertainment papers of 1918. Also, whether his now-pregnant wife traveled with him during this period is unknown as well.

By early 1919 Cliff was back in Chicago, where his son, Clifton G. Edwards, was born on February 13, 1919. It wasn't long before he was back on the road, however. Edwards was next teamed up with singer Pierce Keegan. It was with Keegan that Cliff formed the act Jazz Az Iz, which put the team on the rooftop stage of the Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic in the fall of 1919 in New York City, and was the first New York show which featured Cliff in advertising as "Ukelele Ike" [sic]. This was still not the full-fledged Ziegfeld Follies, but it was a big stepping stone. He also cut a few sides for Columbia Records in New York City with Keegan, but these pressings were never released. It appears that while Cliff traveled, Gertrude stayed in Chicago with their infant son. This would eventually lead to dissatisfaction on Gertrude's part, and a separation in 1920, followed by a divorce in December of 1921. But to the rising star this appears to have been more a peripheral and unfortunate event than it was life shattering. He had also shifted his center of operations to New York by late 1920.

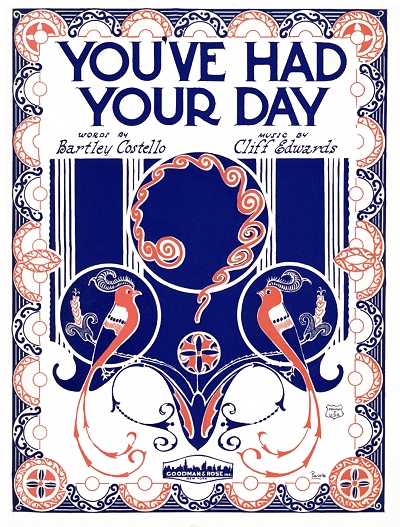

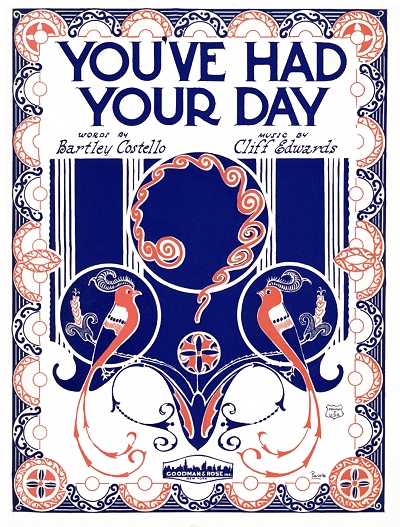

While performing with Keegan, Cliff tried his hand at songwriting with noted lyricist Bartley Costello. His first published work was You've Had Your Day, issued in New York in 1921. He also appeared on Broadway in the Shubert production of The Mimic World, a revue, in August of 1921, although it only lasted for 26 performances. After a year or so with Keegan, Cliff next teamed up with singer and dancer Lou Clayton. This put them on the road from time to time, and he recalled playing in Chicago during their tours. They did not work together on a steady basis, but on and off from 1920 to around 1923. In November of 1920 Edwards was cast in Florenz Ziegfeld's Nine O'Clock Revue, likely singing songs and doing his developing routines. By 1922 he was a part of the primary Ziegfeld Follies show, and toured with the traveling company as well. Also in that company was a chorus girl who had done some acting in New York since 1919, and became a dancer in the Ziegfeld Follies. During a west coast Follies tour, Cliff married Irene L. Wylie in Portland, Oregon, on May 14, 1923. Once he was back in New York he continued his starring role in the Ziegfeld Midnight Frolics.

Even though there had been previous efforts to capture Cliff's magic in a shellac bottle, including some limited releases on the Gennett label, the first recordings of note he did were cut in late 1923 for the Pathé label in Brooklyn, New York. His popularity allowed him to collect a decent bounty of $1,000 per side plus a taste of the profit. They were released on Pathé, their lesser offspring label Perfect Records, and a number of other licensed subsidiaries. The first year or so of issues through 1924 were recorded acoustically, but Pathé, like many other labels, converted to electrical recording at some point in 1925. Given the clarity of Cliff's voice and the timbre of the ukulele, he came across well on all of the recordings. The difference was more notable, however, when he was backed by a jazz orchestra. For some of his solos Cliff pioneered a sound that it seemed only he could make. He called it "eefing," which was a form of scat singing that sounded something like a kazoo (for which it was often mistaken for) and a trumpet. He would use this method clear into the 1950s.

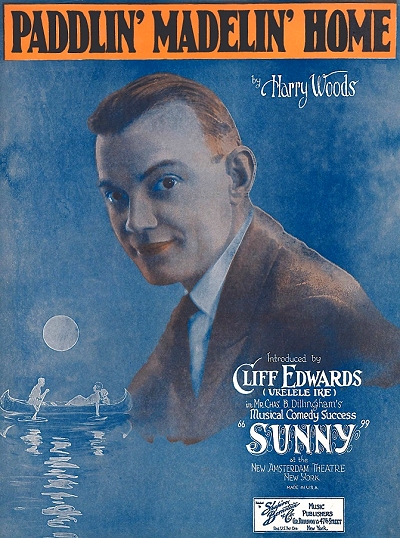

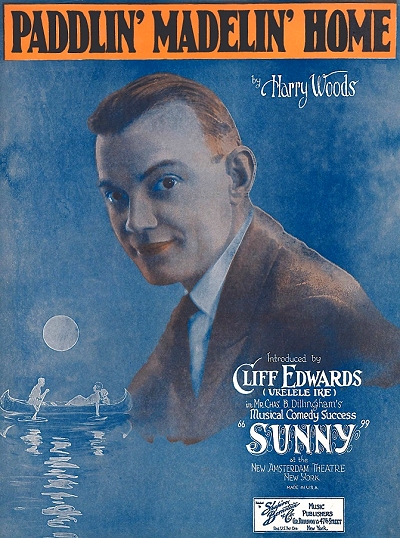

Around the same time, in December of 1924, Cliff landed a spot in the latest musical by George and Ira Gershwin, Lady Be Good. Teaming with Chick Endor, whose songs he sang as the character Jeff, Edwards also had one of their co-compositions, Insufficient Sweetie, interpolated into the show. Some reviews insist that he received more encores than any other performer in the production, which included Fred Astaire and his sister Adele. The number for which he received the most acclaim was his interpretation of the Gershwins' tune Fascinatin' Rhythm. While Edwards' star was already on the rise, the ten months he spent with Lady Be Good cemented his fame, and helped to sell his records. Cliff's picture, usually touted as Ukulele Ike, appeared on numerous sheet music covers from 1924 through much of the rest of the decade as a celebrity performer and therefore tacit endorser of the piece within each of them.

Some reviews insist that he received more encores than any other performer in the production, which included Fred Astaire and his sister Adele. The number for which he received the most acclaim was his interpretation of the Gershwins' tune Fascinatin' Rhythm. While Edwards' star was already on the rise, the ten months he spent with Lady Be Good cemented his fame, and helped to sell his records. Cliff's picture, usually touted as Ukulele Ike, appeared on numerous sheet music covers from 1924 through much of the rest of the decade as a celebrity performer and therefore tacit endorser of the piece within each of them.

Some reviews insist that he received more encores than any other performer in the production, which included Fred Astaire and his sister Adele. The number for which he received the most acclaim was his interpretation of the Gershwins' tune Fascinatin' Rhythm. While Edwards' star was already on the rise, the ten months he spent with Lady Be Good cemented his fame, and helped to sell his records. Cliff's picture, usually touted as Ukulele Ike, appeared on numerous sheet music covers from 1924 through much of the rest of the decade as a celebrity performer and therefore tacit endorser of the piece within each of them.

Some reviews insist that he received more encores than any other performer in the production, which included Fred Astaire and his sister Adele. The number for which he received the most acclaim was his interpretation of the Gershwins' tune Fascinatin' Rhythm. While Edwards' star was already on the rise, the ten months he spent with Lady Be Good cemented his fame, and helped to sell his records. Cliff's picture, usually touted as Ukulele Ike, appeared on numerous sheet music covers from 1924 through much of the rest of the decade as a celebrity performer and therefore tacit endorser of the piece within each of them.It should be noted that the ukulele had achieved only minimal popularity as a stage musical instrument in the 1910s, and was largely associated with the recently acquired United States territory known as Hawaii. Its origins were actually in Spain and Portugal, developed as a smaller and more portable guitar, and it was sometimes called a soprano guitar. Performances at the 1915 Pan-American Exposition in San Francisco which included the instrument helped to elevate it from a novelty to a viable accompaniment tool. However, it was through performers Roy Smeck, who first played the instrument on early sound films, and Cliff Edwards, that it achieved national popularity in the 1920s, and became the sidearm of college boys everywhere. So, it stands to reason that all of the music sheets that Cliff endorsed also had tablature or chord symbols for the ukulele. Pianist May Singhi Breen, who was the same age as Cliff, received a ukulele in 1922 and immediately took to it. She instantly became the most important arranger for the instrument within the next two years, and between her insistence to publishers that they would benefit from including chords for the uke within their sheet music and Cliff's rising popularity, ukulele sales around the world increased exponentially throughout the rest of the decade. May, however, was more of the behind the scenes advocate whose name appeared on countless arrangements, while Cliff was the front man who proved what could be achieved with a mere four strings and two hands. It should further be pointed out that he played at least four sizes of ukes, from a very tiny pocket model to one almost the size of a full guitar.

May, however, was more of the behind the scenes advocate whose name appeared on countless arrangements, while Cliff was the front man who proved what could be achieved with a mere four strings and two hands. It should further be pointed out that he played at least four sizes of ukes, from a very tiny pocket model to one almost the size of a full guitar.

May, however, was more of the behind the scenes advocate whose name appeared on countless arrangements, while Cliff was the front man who proved what could be achieved with a mere four strings and two hands. It should further be pointed out that he played at least four sizes of ukes, from a very tiny pocket model to one almost the size of a full guitar.

May, however, was more of the behind the scenes advocate whose name appeared on countless arrangements, while Cliff was the front man who proved what could be achieved with a mere four strings and two hands. It should further be pointed out that he played at least four sizes of ukes, from a very tiny pocket model to one almost the size of a full guitar.In 1924 Cliff had his largest published compositional output, followed by a handful of tunes over the next two decades. While a number of the pieces were written with seasoned lyricists or composers, he did manage a few of his own hand, although they were likely arranged and scored by staff members of the publishers, given his notational illiteracy. Some of the pieces exist only as a performance on disc or film. One of the more notable and enduring efforts from the mind of Edwards were his books on ukulele performance. Among his first was a comic book song geared towards a younger audience, but he also created some method books that would remain in prints and reprints for several years. These book were likely ghost-written to some degree. Whether or not Breen was involved with any of his efforts is also unclear, but as she usually was given full credit for her work, it would skew towards unlikely.

Following Lady Be Good, Cliff made another splash in the equally successful musical Sunny, written by Oscar Hammerstein II and Jerome Kern, which ran for 517 performances from 1925 to 1926. Among the pieces that Cliff performed and recorded from that show was Paddlin' Madelin' Home by Cliff's friend Harry Woods. Unfortunately the Victor electrical recordings were poorly done, and do not showcase the casts' talents well. It didn't stop this disc from becoming very popular as well, as Cliff's recording of Paddlin' Madelin' Home climbed to number three on the Billboard charts in 1925. Among his other popular recordings were California, Here I Come; Toot, Toot, Tootsie! Goo'Bye! (recorded even before Al Jolson made a splash with it); It Had to Be You; I'll See You In My Dreams; Hard-Hearted Hannah; and another song he introduced and went far with, Sunday.

Edwards' next big stage success was in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1927, memorable for its equally captivating star Eddie Cantor who was riding his own wave of fame for the song and play Makin' Whoopee, and Ruth Etting who introduced Shakin' the Blues Away. When he wasn't with the big shows, Cliff kept himself busy on the B.F. Keith-Orpheum and Pantages vaudeville circuits. In fact, just to keep working at times he would seek out gigs with in cheap vaudeville or burlesque theaters, usually as the major attraction for an otherwise average show. He would even participate in local shows while on tour with larger productions. On the side he would make some recordings of the more unsavory material, which although it was not advertised, could still be sold at his low vaudeville and burlesque shows and in certain record shops.

This included works like Who Takes Care of the Caretaker's Daughter (While the Caretaker's Busy Taking Care), and I'm a Bear in a Lady's Boudoir. Cliff always had a ukulele handy with a list of his current repertoire affixed to the back so that he could reference what pieces currently in his repertoire at a moment's notice.

|

This need to constantly perform, possibly driven by financial distress even this early in his career, would persist throughout Cliff's life. In the mid to late 1920s he was pulling in a very tidy sum of $4,000 or more per week for the stage work, in addition to payments and royalties for sheet music and recordings. As Cliff had been poorly educated as a child, and perhaps poorly advised as an adult, he spent his money as if there would always be more coming in. This included a fresh supply of ukuleles, a small expense, accompanied by luxury items such as lodging in fancy hotels on tour, and driving fine cars. Among them was a Stutz Bearcat that had fine leather seats and a custom body, a lavish expense for that time. He would later buy a Packard, a very distinguishable high-end automobile. It is possible that some of his expenses were associated with women as well. Edwards was no choir boy, but little was reported about his indiscretions, if any. However, based on his marital track record, it was likely a factor in his constant financial shortfall, as were alcohol and, as time progressed, drug abuse.

While on tour at the Orpheus Theater in Los Angeles at a critical juncture in the history of cinema, Ukulele Ike was seen by Louis B. Mayer's MGM studio prodigy, Irving Thalberg. That time was shortly after the musical sound film The Jazz Singer had become a sensation, and studios everywhere were grappling with how to best use the new technology. As recording methodologies were still developing, and the noise of cameras in the days before boots were adopted created issues such as limited movement ability, most of the early films were music-based, since it was easier to record and friendly to locked-down cameras. MGM had recently completed Broadway Melody (1928), which would get some notoriety at the first Academy Awards event the following year. Cliff's ebullient personality as both a singer and potential comic Master of Ceremonies caught Thalberg's attention, and he engaged the performer for an upcoming film that was his first effort with sound. (There is a possibility that Edwards had appeared in a silent film a few years earlier, but that effort was uncredited, and apparently no longer extant).

Cliff's ebullient personality as both a singer and potential comic Master of Ceremonies caught Thalberg's attention, and he engaged the performer for an upcoming film that was his first effort with sound. (There is a possibility that Edwards had appeared in a silent film a few years earlier, but that effort was uncredited, and apparently no longer extant).

Cliff's ebullient personality as both a singer and potential comic Master of Ceremonies caught Thalberg's attention, and he engaged the performer for an upcoming film that was his first effort with sound. (There is a possibility that Edwards had appeared in a silent film a few years earlier, but that effort was uncredited, and apparently no longer extant).

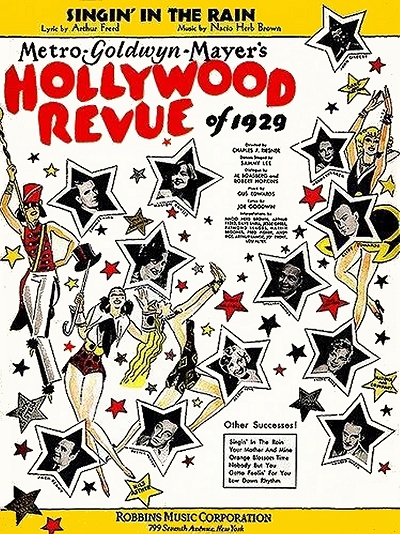

Cliff's ebullient personality as both a singer and potential comic Master of Ceremonies caught Thalberg's attention, and he engaged the performer for an upcoming film that was his first effort with sound. (There is a possibility that Edwards had appeared in a silent film a few years earlier, but that effort was uncredited, and apparently no longer extant).For Hollywood Revue of 1929 (available via on-demand DVD from the Warner Archives website), Cliff shared Master of Ceremony duties with comedian Jack Benny. A song by studio writers Arthur Freed and Nacio Herb Brown was selected for introduction by Cliff. It became the lynchpin of the film, and inspired another song-titled film nearly a quarter century later. Singin' in the Rain, both chorus and verse, was introduced by Ukulele Ike at a couple of points in Hollywood Revue of 1929, including a sensational ending featuring all of the MGM stars repeating the song ad nauseam in front of an ark in a moderate rain, and in two-strip Technicolor. Just the same, it was the song that movie-goers were humming as they left the theater, and one that would be oft-repeated in films by other personalities up through 1952 when Gene Kelly immortalized it in perhaps the best musical of all time, Singin' in the Rain. For Cliff, it sold records, and from 1929 until 1931, as sound technology was installed in theaters all around the United States and Canada, it brought him into venues where he had previously only been a name or a personality on a record. In short, it made him rich and famous. One of those conditions would not last for long.

Following Hollywood Revue of 1929, Cliff appeared in 22 additional films at MGM. Among those actors that he befriended there was Joseph "Buster" Keaton, who after years of making his own silent films had been bought out by MGM and was now an unhappy contract player there. Given than Cliff had moved to the West Coast in order to play in films, taking his wife away from her friends in Manhattan,

his marriage was clearly on the rocks by late 1929. Keaton had also experienced somewhat public marital issues. Combined with his reluctance to do things the MGM way, but needing to work, Keaton was in a downward spiral at this time.

|

Keaton and Edwards had enough in common that they became drinking buddies and comrades, in addition to doing at least three films together. Among the most interesting of them that shows their musical dynamic was Doughboys from 1930. It includes a scene in which Cliff combines his ukulele, drumming and scatting skills, drumming on the strings of the uke while Keaton provides the chording and a bass line. However, off screen both became involved in some self-destructive epic binges as well. Keaton would eventually pull out of this hole to a degree, but Edwards simply delved deeper into alcohol abuse, and soon was battling heroin and cocaine from time to time. It may have affected his work on some days, but the volume of work he did for MGM indicates that he was still popular - at least with the public.

The 1930 census showed Cliff living at 8221 Sunset Blvd. in Hollywood in a hotel or apartment with a number of other movie types, including writers, artists and executives. Missing from that location was Irene Edwards, who was living a couple of miles off near the Wilshire Country Club with her divorced mother, Effie Wylie. Irene was in the beginning of what would become a rather public and protracted divorce trial with her husband. Accusations were lobbied from both sides, and proceedings routinely monitored by show business reporters.

Who started it was unclear, but it appears that initially Irene had filed for separation in 1930, then Cliff sued for divorce based on Irene's indiscretions with blues singer Austin J. "Skins" Young in 1931. By August of 1930, Cliff, the primary breadwinner who had already earned well over $1 million during the past several years, was told to pay alimony to Irene. However, he had already given her $10,000 in a property settlement, and claimed, with some accuracy, that he was broke. "If my songs are as valuable as they say they are, I'll sing a couple for her - but that's the best I can do." He also pointed out that by the terms of their separation agreement that Irene was asked to maintain a "high personal moral standard," which she evidently have violated. The judge ordered $250 weekly alimony in September, but to be paid out of the settlement already rendered.

Proceedings went on through 1931, during which Cliff did his filing and asked for (but did not receive) recision of the initial settlement. In the end, Cliff was to give nearly half his income to Irene for life. Sadly, the joke was on both of them as his income and his profile both diminished over the next decade.

|

In the meantime, in spite of all of the trouble, Cliff continued to do films for MGM, and then moved to RKO. He was in at least fifty films during the 1930s. Among those that he appeared with, comprising an impressive list of 1930s Hollywood royalty, were Keaton, Clark Gable, Joan Crawford, Barbara Stanwyck, John Gilbert, Marion Davies, Helen Hayes, Robert Montgomery, Rosalind Russell, Jean Harlow, Spencer Tracy, Cary Grant and future politician Ronald Reagan. He also started working in radio around 1932, starting with a show on the CBS network. In spite of all of this work, in which he was never really a star, but still paid well, Cliff was not immune to the financial situation of the Great Depression. This did not bode well for Cliff or Irene, or for his next wife.

Even though he had been separated and in divorce proceedings for some two years, it was reportedly not until early August of 1932 that the final divorce was granted to Cliff. Throughout the year he had been linked with another actress, a "starlet" named Nancy Kelly, who was working as Nancy Dover. It was also reported that his mother, Nellie, now living in Davenport, Iowa, died on June 20 [difficult to confirm]. Within a couple of weeks after his final divorce, Cliff was married to Nancy in Las Vegas, Nevada, on August 31, 1932. It would not take long for Nancy to figure out that she was not marrying a millionaire. Trouble came in January of 1933 in Chicago, Illinois, where Edwards was working in vaudeville between films. He was served with an injunction and restraining order that disallowed him from leaving Illinois until additional support was paid to his first wife and his child. His son, Clifton, had lost both legs in a railroad accident, and they were asking for $200 per month of support. By March both parties had settled on $30 a month instead. Soon after that, Cliff filed for his first bankruptcy, much to Nancy's chagrin. By June of 1933, both were sued [by who is unclear] for collectively hiding assets. Nancy soon went her own way, reconciling on a couple of occasions. The couple did not obtain a legal divorce until late 1936, by which time she was working as Judith Barrett. This sent him into a further spiral of financial woes, which included gambling debts and some additional demands from Nancy cum Judith.

The public still took well to Ukulele Ike, as did movie and stage producers. In 1934 he performed in the film version of George White's Scandals, repeating his appearance the following year in George White's 1935 Scandals. This further manifested itself into Cliff replacing departing star Rudy Vallee, who quite over a pay dispute, from the New York stage version of the Scandals, making Cliff the star of the 1936 show on Broadway.

As the decade progressed he was more frequently cast as the sidekick in westerns, singing a song here and there, and generally just uttering humorous lines in his infectious voice. But his two biggest roles of that era would ironically, or perhaps justly, be centered around his melodious vocal chords, and not include his visage.

|

In 1939 Cliff landed a role in one of the two biggest films of the year. Too tall to be a Munchkin, he was actually cast in the other mega-hit, the epic Civil War drama Gone With the Wind. In the pivotal and poignant scene in which was initially to appear on camera, Cliff played a southern soldier reminiscing from his Atlanta hospital bed about the past as Vivien Leigh, playing the primary character of Scarlett O'Hara listened wistfully. Her wistfulness turned out to be more interesting to the director, so Cliff's voice is heard, even though he was never shown. This, however, would not immortalize the actor as well as his next role, who appeared in the 1940 census in the greater Hollywood area listed as an actor.

When they were casting, and actually refining, the characters for the upcoming animated film Pinocchio, one of the characters that jumped out at Walt was actually a minor one from the original book by Carlo Collodi about the wooden puppet who wanted to be a "real boy." It was not the termite that had been considered, but a cricket. Given the common non-vulgar expression of the time, "jiminy cricket" (ironically enough uttered by Dorothy in the beginning of The Wizard of Oz in 1939), the name became evident, and helped to fill in the character. However, finding the voice was a different matter.

Among the fans of Ukulele Ike were some of the personnel at the Walt Disney Studios, including Walt Disney himself. Just the same, Cliff was reportedly the 37th actor who was auditioned for the role of Jiminy Cricket.

The original perception of Pinocchio's virtual conscience was as a "pompous old fellow - a windbag." When they decided on Cliff for the part, Walt and others knew that they would need to alter the character to better suit his personality. So it was that Jiminy Cricket became a sidekick much like the ones Cliff had played in other films. But this time there was a difference.

|

Disney films had been centered around music since Mickey Mouse had first played cats, cows and other creatures as instruments in Steamboat Willie in 1928, and was the focus of their other 1940 film, Fantasia. So having the right music, often character driven, was a key element in their success. So it was that frequent Disney contributor Leigh Harline was engaged along with lyricist Ned Washington to compose for Pinocchio. The result included the opening number which, much as Over the Rainbow had been considered to be a song in passing, became as iconic, and perhaps even a bigger hit over time. When You Wish Upon a Star, which was sung over the sweeping opening credits of Pinocchio, was a highlight in the film, and soon a hit record. It later became a theme for several seasons and iterations of the Sunday night Disney series on television, and since has been incorporated into their film and video logos, ring tones, and even the musical horn blasts on their fleet of cruise ships. It even has survived as a jazz standard by any number of fine musicians from Bill Evans to Dave Brubeck. Perhaps no other 20th century song, specifically the original recording, is so closely associated with childhood memories as When You Wish Upon a Star, especially given the beautiful vocal as rendered by Edwards. His portrayal of Jiminy Cricket also helped to make the film a success. Even though none of the actors received any screen credit for their roles, it was clear to the public who was behind the song.

While the film and record were financial boons for the ukulele laden entertainer, he still continued to have financial issues due to excess, and never again rose to the level of stardom afforded him by Disney or MGM. He filed for bankruptcy once again in 1941. After voicing a crow with the unfortunate name of Jim Crow in the 1941 Disney film Dumbo, Cliff continued in films and did radio work, ultimately performing on all four networks of the period (CBS, NBC-Blue, NBC-Red and MBS), and on ABC once it was formed out of the remains of the NBC Blue network. His 1942 draft record showed his employer as R.K.O. Pictures in Hollywood. However, after the war, Cliff lived for a time in New York in the late 1940s on a former Navy boat converted into a floating home on the East River.

In 1949 Cliff became a television pioneer on his own New York show that had a brief run on CBS. He evidently also did some kind of stage work, as the 1950 census, taken at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel on Park Avenue, showed him to be a stage actor. Despite some short term success, this flurry of work was was followed by yet another bankruptcy. His plight continued into the 1950s with more drug addiction and bouts with alcohol. In early 1952 Cliff traveled to Australia for a four week tour, and ended up staying down under for some 15 months, playing his ukulele and entertaining a new audience. While this was inspiring to him for a time, he ultimately returned to the United States in 1953, admitting that the ukulele would likely never again become so wildly popular as it had been in the 1920s, "even if [radio entertainer and singer] Arthur Godfrey learns to play it."

In early 1952 Cliff traveled to Australia for a four week tour, and ended up staying down under for some 15 months, playing his ukulele and entertaining a new audience. While this was inspiring to him for a time, he ultimately returned to the United States in 1953, admitting that the ukulele would likely never again become so wildly popular as it had been in the 1920s, "even if [radio entertainer and singer] Arthur Godfrey learns to play it."

In early 1952 Cliff traveled to Australia for a four week tour, and ended up staying down under for some 15 months, playing his ukulele and entertaining a new audience. While this was inspiring to him for a time, he ultimately returned to the United States in 1953, admitting that the ukulele would likely never again become so wildly popular as it had been in the 1920s, "even if [radio entertainer and singer] Arthur Godfrey learns to play it."

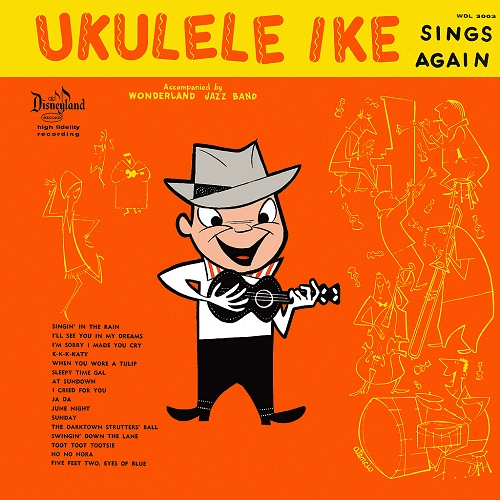

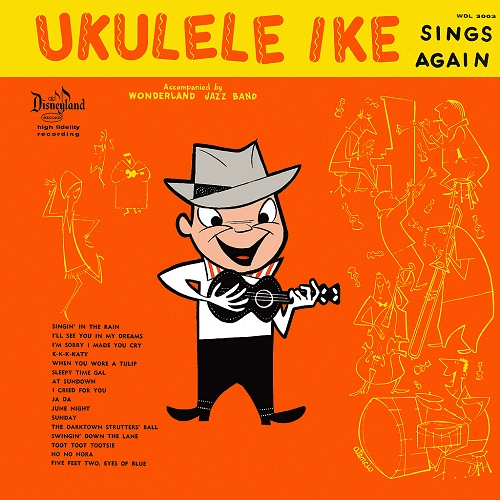

In early 1952 Cliff traveled to Australia for a four week tour, and ended up staying down under for some 15 months, playing his ukulele and entertaining a new audience. While this was inspiring to him for a time, he ultimately returned to the United States in 1953, admitting that the ukulele would likely never again become so wildly popular as it had been in the 1920s, "even if [radio entertainer and singer] Arthur Godfrey learns to play it."When Walt Disney entered into the television picture in 1954, he and his staff knew to draw on properties and characters that had made the studio franchise so successful, but also knew they would need new material. Knowing about Cliff's unfortunate situation and his problems, the studio nonetheless hired him on to record material for the Mickey Mouse Club show, and later for the Disneyland and Wonderful World of Color weekly shows. Musical director George Bruns, in an attempt to further help the aging and deteriorating vaudevillian, arranged and recorded an album with Cliff titled Ukulele Ike Sings Again, which was backed by Bruns' Wonderland Jazz Band, and featured many of Edwards' old numbers from the 1910s through the 1930s. Among those was the first released recording of the song that made him marginally famous nearly four decades earlier, Ja Da. One of many recordings that Cliff made for both Disneyland Records and its sibling company, Buena Vista Records, it was not a great income-producing hit by any stretch.

From the late 1950s into the late 1960s, Cliff performed here and there, and did a few voiceovers. It was said that he hung around the Disney Studios in Burbank, California, hoping to find work now and then. Even though Walt and other staff members, such as Firehouse Five Plus Two co-founder and animator Ward Kimball, had a clear fondness for Cliff, they were also leery of facilitating his habit or giving him false confidence, so tried to help him in other ways, which included buying him lunch and listening to his tales of the old days on stage. Recordings made in the 1960s, some of which were made after frequently missed dates due to the alcohol, clearly show the ravages of a hard life on both his voice and his comic timing. By 1969, now approaching age 74, and perhaps living on borrowed time, Cliff was admitted into the the Virgil Convalescent Hospital in Hollywood. His two-year stay there was funded in part by MediCal and the Actor's Fund of America, which had funds designated for such cases,

and in the background with quiet and deliberately unheralded assistance from the Disney Corporation, probably thanks to Walt's brother Roy Disney, and musicians such as Ward Kimball and his associates.

|

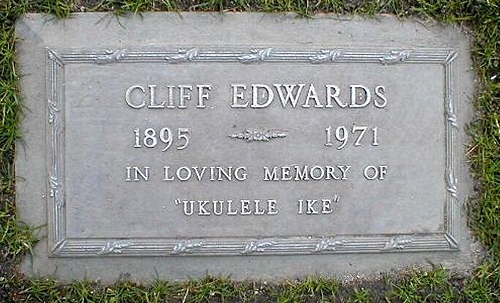

On July 17, 1971, shortly after his 76th birthday, Cliff Edwards was taken by a myocardial infarction at the Virgil Convalescent Hospital. His case and history were largely unknown among the staff, so they did not publicly report it for several days, and Cliff remained unclaimed in the L.A. County morgue. Around the time he was designated to go to the UCLA Medical School for student training, it came to the attention of the Hollywood and Disney communities through the efforts of radio station KMHO in his native Hannibal that Cliff was gone, and they decided to honor him with something better. While Disney reportedly initially offered to take care of Cliff's remains, the Actor's Fund and the Motion Picture and Television Relief Fund instead insisted on the duties, having him buried in an actors' plot in North Hollywood at Valhalla Memorial Park. Just the same, they praised the Disney Corporation for looking out for Cliff's well-being in his final years, which was part of their reason for handling his burial. In 1984, after it was brought to their attention that Cliff did not have a sufficient grave marker, the Disney Corporation provided a simple one for him at Valhalla.

In spite of his vices and travails, Cliff Edwards, a product of both the good and bad of the ragtime era, is fondly remembered by millions either as Ukulele Ike or Jiminy Cricket, and by some as Cliff Edwards. In 2002, Cliff's original Victor recording of When You Wish Upon a Star [Matrix 261546] was inducted into the Grammy Awards Hall of Fame. It has also earned a position as number seven of the 100 Greatest Songs in Film History, as per the American Film Institute. Cliff has further been honored by the Ukulele Society of America on various occasions. At worst he remains a cautionary tale of what fame can do to even the nicest and most likable of entertainers, but fortunately, his legacy is mostly about the good music he left behind for generations of children.

Known Compositions

Known Compositions