Early Life

Fred Van Eps was one of three boys born in Somerville, New Jersey, to Dutch settler descendants John Perry Van Eps and Genevieve Hillyor "Jennie" Bergen, the other two being William Perry (1874) who died in the early 1880s, and another son also named William Perry (6/1885). The 1880 census showed John to be a jeweler, and he was, in fact, a watchmaker. Van Eps was also hosting his sister and mother in addition to one domestic in his home, so the family was likely relatively well off. Note that a few sources, including newspapers of the late 1890s and early 1900s, sometimes spelled the name as Van Epps, but official records have historically all used Van Eps. In a 1955 interview with writer Jim Walsh that was published in the January, 1956, edition of Hobbies Magazine, he also insisted that his name had always been Fred, never Frederick [or possibly Frederich]. However, the 1880 census indicates otherwise, so he may have simply never remembered that fact.

Gifted with an inclination toward music, Frederick was encouraged by his father to study the violin as early as age seven. There were indications that he played it in a couple of recitals as well. According to his 1955 recollection, in the early 1890s he became enamored with the banjo as it was gaining popularity among white players, particularly on the East Coast, and having specifically heard it played by George W. Jenkins, a conductor on the Jersey Central Railroad. John was not very supportive of his son's desires to move to a less-cultured instrument, but Jennie decided to indulge Fred, not only getting him his own banjo, but engaging Jenkins to teach him how to play. Contrary to the classical training he had received on the violin, Jenkins, who had no traditional music training of his own, taught Frederick by rote, showing him tunings and finger positions as he passed on his own repertoire of tunes.

In 1892, John moved his family about a dozen miles east to Plainfield, New Jersey. It was there in either late 1893 or early 1894 that he recalled hearing his first banjo recording, a United States Phonograph Company cylinder of current New York banjo champion player Sylvester "Vess" Ossman, playing The White Star Line March. However, as this was released in 1896, either the remembered date was wrong, or he instead heard one of Ossman's North American Phonograph cylinders, possibly White Star Line, or likely Washington Post March. In any case, Fred started collecting the brown cylinders of Ossman and others playing banjo, and learned all he could from repeated plays of each tune. In order to do this, he had to obtain a phonograph, not a cheap device in those days, but was able to quickly pay for it as he remembered in his 1955 interview with Jim Walsh:

...I bought a Type M Edison two-minute cylinder phonograph. It cost me $100 — a lot of money then — but I paid for it the next week by attaching 14 ear tubes, taking it to the Fireman's Fair and letting people listen at five cents a play. I've got those tubes yet that fit in your ears. Lots of people came up who had never heard a phonograph before. Mine was the first in Plainfield, which even then was quite a decent sized city. To tell the truth, the machine was something of a nuisance because it was so much of a curiosity. People would come to my home and ask to be allowed to listen to it. We couldn't refuse them, but all such favors took time.

...My chief purpose in getting the machine was to practice making my own records, and I began to do home recordings almost as soon as I obtained it... I got my blanks from the [U.S. Phonograph Company] people — 20 cents each. All the machines in those days had a shaving attachment. If you didn't like the results, you simply shaved them off and tried again...

In order to placate his father, Fred spent time learning watchmaking, and helping him with repairs, but working on perfecting his banjo playing during his breaks.

His efforts were so valuable to the business that his father, who was not a proponent of higher education, pulled Fred out of school before he was even sixteen, something Van Eps later regretted. However, he kept plugging away at the banjo as well as learning the jewelry and watchmaking trade. Music pulled at him, and he knew that it was the avocation he was best suited for. So in 1897, eighteen-year-old Fred decided to try to break into the recording business. He set down two of his performances to cylinders at home, then set out to West Orange, New Jersey, to the Edison National Phonograph Company.

|

When Thomas Edison first invented what would become known as the phonograph, his intention was that it would be an ideal instrument for dictation and the capture of oration. Similar inventors, including Alexander Graham Bell, saw it as a means for capturing telephone conversations or even telegraphy. Edison eschewed the idea that his invention should be used for the reproduction of music. However, other inventors sought to improve the acoustical capture and playback properties of phonographs, and by the mid-1890s both Berliner flat discs and Columbia cylinders were being sold to the public with the idea that they could bring great performances into their homes. Both formats had inherent flaws. Cylinders retained a constant speed for either two or four minutes (depending on how the machine was geared), but until around 1902 or so could not be produced in mass, requiring performers to cut ten or so at a time in a day-long session of dozens of performances of the same piece. Those in turn could be copied via a tube to more cylinders, but with a significant loss in fidelity. As for the Berliner-style records, as the needle got closer to the center of the disc the rate of speed through the groove was significantly reduced, changing the fidelity. However, they were easy to reproduce from a single master, allowing for tens of thousands of copies of a single performance. Both, however, were not all that friendly to instruments like the guitar, double bass, or piano, as early recording horns and studio techniques simply could not capture the full breadth or nuances of these instruments.

When record companies started looking for material for the public to take home with them, vocalists were at the top of the list, usually with a small but loud ensemble. However, for instrumental pieces of popular songs, the banjo had a clear advantage over other instruments in the late 1890s,

as it was not only easy to capture by most recording horns, but would carry further on the average playback horn as well. This property, a knowledge of current popular works, and a name that the public knew, made Fred and his peers valuable commodities in the early days of acoustic recording. A little late to the game, Edison started issuing music discs in 1896, including some recorded by Vess Ossman. Although Edison himself was not a big proponent of popular music, he eventually put others in charge of the recording end of his enterprise, stipulating that fine classical works would always be available on his label.

|

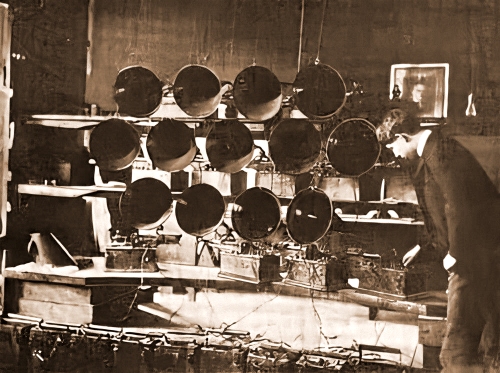

Fred was, in his words, given "a fairly good brush-off" by the Edison folks when he first arrived, but finally persisted and got someone to listen. He was ultimately hired for a regular Wednesday afternoon gig, recording up to 40 cylinders each session (likely of one or two repeated tunes per day), for which he received $1 per recording (which may have yielded a dozen cylinders at a time on average). This $40 was, of course, much better than the $16 per week that his father was paying him. His first accompanist was pioneering studio pianist Frank P. Banta, father of the future novelty piano whiz Frank Edgar Banta, with whom Fred would also work in the late 1910s into the 1920s. The elder Banta had learned to play piano in the 1870s and 1880s as a rough tuner in a piano factory, the person who got the piano up to pitch before the final tuning was done. He was among the first pianists and conductors in the recording industry, which was not particularly acoustically friendly to piano solos. However, they worked well as an accompaniment instrument for singers and banjoists. As for his memory of the recording process:

[Was I] nervous during my first recording engagement? No, I don't think so. I always practiced slowly, to gain sufficient accuracy, and I was already used to making records at home. They had six or seven horns lined up in racks, because in those days there was no duplicating. Every record was an original. The one in dead center usually was best and brought a higher price. [There is some truth to this amongst collectors, but no verification was found in trade magazines of the era.] Actually, I didn't pay much attention to the size of horns, the thickness of diaphragms and other technical subjects. I wasn't supposed to. If I had carried tales from one recording laboratory to another I would have been in a hornet's nest.

Gaining Ground

Van Eps was initially working in the shadow of older and more established banjoists who were known both on record and for their live stage performances. Among them was Ossman, who in the late 1890s and into the new century was considered the "King of the Banjo."

Another one was vaudevillian Ruby Brooks, who was more of a stage player than recording artists, and the team of Cullen and Collins who initially recorded for Columbia in Washington, DC, before that company was moved to New York. However, the shadows were not all that daunting, and at times lucrative. Whenever Edison ran out of Ossman titles that were particularly popular, or master discs were damaged in some way, Fred or other performers were sometimes called on to recreate them for a new batch. Not all of the recordings attributed to Ossman were necessarily recorded by him, and may have been by Van Eps or Brooks. Columbia and Victor also used this practice in the early years of recording, but Fred only did a couple of Ossman remakes on Columbia in the early 1900s, and a few for Victor more than a decade later.

|

For the most part Fred was just called on to play popular tunes to bolster the Edison catalog. However, his star was rising slowly, and he was often engaged to play with local bands and orchestras in central New Jersey. Van Eps sometimes worked as a banjo instructor in a Plainfield studio as well. The 1900 census showed Fred, still living with his parents and younger brother in Plainfield, working as a musician. Some of that was done with bands and orchestras from central New Jersey into New York City, on occasion covering for some of the more famous banjoists when they had conflicting gigs. As the instrument grew in popularity after 1900, banjo duets and even ensembles started to spring up around the country.

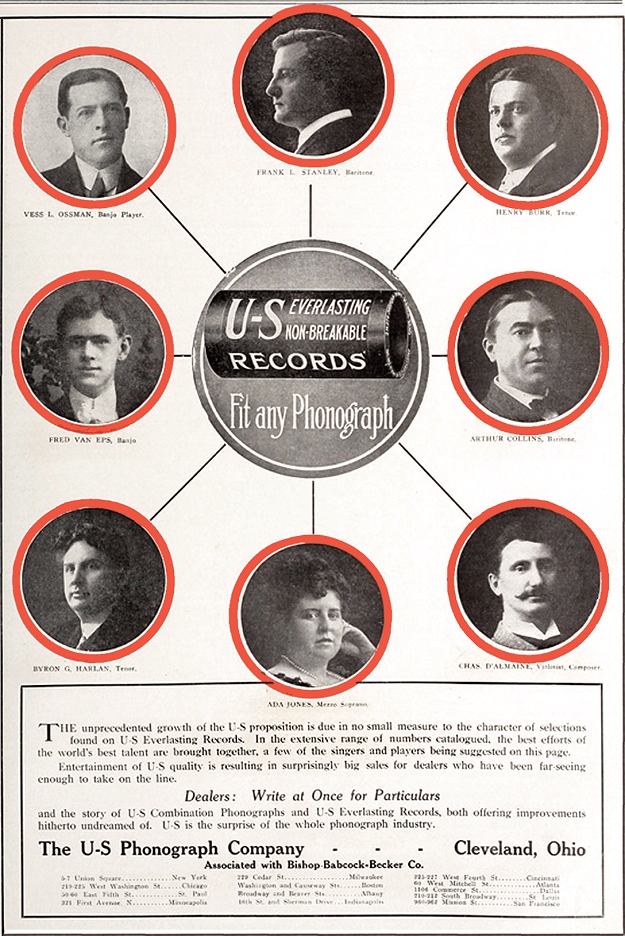

Fred played one of his first recorded banjo duets for Columbia Records in December of 1903, his only known work from that era with fellow banjoist William D. Bowen. They recorded both a cylinder and a disc of Jack Tar March, which had also been recorded by Ossman around the same time, so may have been a cover. It would be more than seven years before Fred recorded for Columbia again. However, over the next year, both Van Eps and Bowen filled a number of engagements as an alternate to Ossman, thanks to his booking office. The 1905 New Jersey State census, taken in Plainfield, showed the Van Eps family still residing together. Given Fred's skill and reliability, and even though he did not share Ossman's national reputation at the time, the studios and night spots kept Fred busy. He recorded for the Zonophone, Everlasting and Indestructible labels over the next few years,

including a cover of Scott Joplin's Maple Leaf Rag in 1908 that echoed the same work Ossman had done a year prior for Columbia. On a few dates he was joined by his younger brother Bill, who was a fine banjo and mandolin player.

|

In 1906 Van Eps was married to fellow musician Louise Abel. Her mother, Sarah Abel, had written two operettas, so there was music in their blood. Louise soon gave the couple two sons, Fred, Jr. (7/1907) and Robert B. (3/1909), who also had music in their future. The 1910 census showed them residing in Plainfield, and curiously listed Fred as a "manufacturer of banjos." Although he engaged in that practice years later, it is possible that while he was waiting for that big break, he started the process of what would be innovative new ways to not only build, but play banjos more effectively. That big break came in early 1911 when Fred was engaged by Victor Records, who had been using Ossman since 1901, to supplement their output of popular music played on the banjo. Starting with lively one-steps The Burglar Buck and Rag Pickings, both better than moderate hits for Van Eps and Victor, he eclipsed the increasingly busy Ossman's output by nearly triple during 1911, and in short order, Van Eps had a name and a reputation that was selling records. That same year found him recording once again for Columbia, and continuing with Everlasting and other smaller labels. Where Ossman had become more of a stage and theater banjoist, Van Eps was now firmly established as the go-to studio guy, even though he also continued to do live work for special events.

Two more sons were born to Fred and Louise, including John A. (9/1911) and George B. (8/1913). However, there was disharmony within the household, possibly from Fred's busy schedule, which likely left Louise alone to raise their children. The 1915 New Jersey census showed the family of six living in Plainfield, but whether Fred was actually in the household at that time can be argued by something brought up in his 1955 interview. In that, he talks about his second wife, Florence Ethel "Flossie" Schoffstall of Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania, and references their 43 years together. As she died in 1954, that would infer that they were together since 1911 or 1912. Louise was not mentioned in that interview. It could be that he misremembered the number of years, which was more likely 33, or less likely that he had simply left Louise to live with Florence until they could be married. Fred's 1918 draft record also cited Louise as his legal wife, making the latter situation less probable. However, the 1920 census showed Fred living with his aging parents Plainfield while Louise was living on Long Island with their four sons. Later records confirmed that the couple divorced, perhaps in the early 1920s, but no official record was located. In 1922 Louise placed advertisements in the Freeport [Long Island, New York] Daily Review as a teacher of piano and voice.

The Banjo King - On the Record(s)

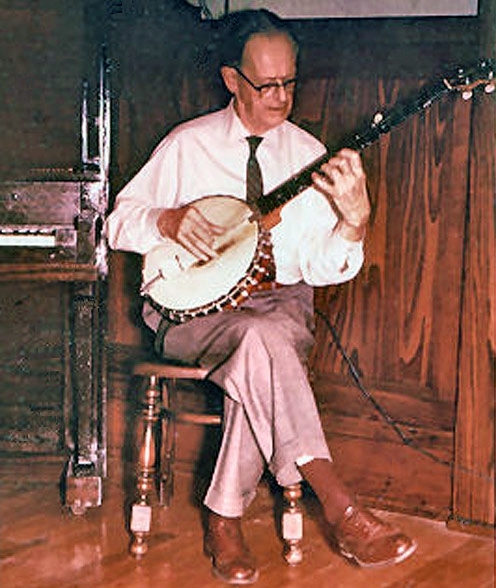

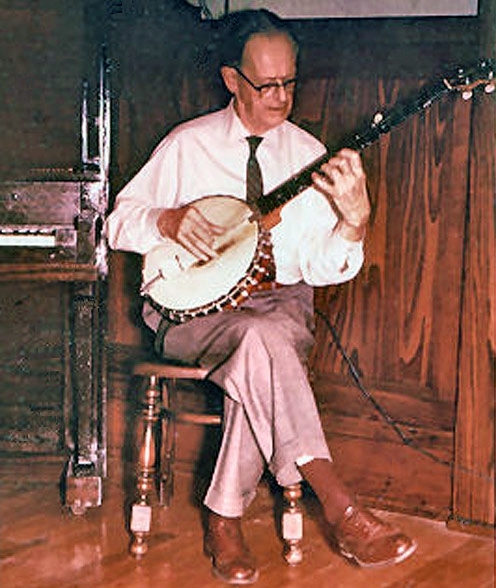

During the 1910s, Fred clearly came into his own, and stood as unique amongst his peers due to his picking style. He tended to use just his fingers as opposed to a pick or plectrum, giving a different tone, and also giving him more velocity and ease of playing melodies. He noted that many mandolin and guitar players came from the Midwest to New York to study what he and Ossman did, but ultimately returned home unable to replicate their dynamic performances. According to Van Eps this led to the style of tuning in fourths that created the tenor banjo, which was better for chord playing, but not so much for melody. They also built hybrid instruments that were like mandolins, where they had the mandolin neck with the banjo drumhead. These never became big sellers with the public, and did not record all that well, but since have been used for folk music due to their interesting variances in tone.

In order to stand out, Fred needed a steady group to work with. Unfortunately, his original accompanist, Frank P. Banta, had died quite young in 1903. However, in the early 1910s, Van Eps found a very fine player who was as adept as arranging piano rolls as he was creating clever compositions.

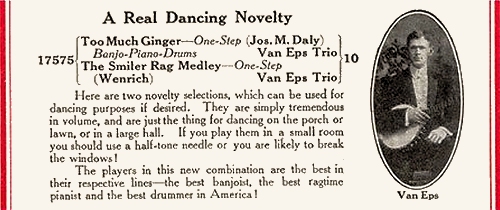

So it was that the early incarnation of the Van Eps Trio included pianist/composer Felix Arndt, along with Fred's younger brother Bill on either banjo or mandolin. Up until that time, the most popular banjo trio had been Vess Ossman's, with Audley Dudley on mandolin and George Dudley on the massive 36-string harp guitar. However, improvements in horn construction and changes in the recording diaphragms made the recording the piano more viable in the 1910s, so a cleaner sound evolved with the Van Eps group.

|

When Fred first met Arndt, over a decade younger than himself, he was a fledgling arranger and demonstrator for publisher M. Witmark working for around $20 a week. Van Eps was impressed with his skill and style, and tried to recruit Felix against his European mother's objection, since she did not want him leaving a secure position to work as a performer. Fred told her that he would guarantee Felix $50 a week, but "if couldn't make $100 I didn't want him." She consented, and it launched a fruitful but short career for the talented youth.

Shortly after the Van Eps trio debuted on disc, Bill was replaced by Victor staff drummer Eddie King at the insistence of a Victor producer, a move that Fred did not favor. In different configurations, Arndt stayed with Van Eps through around 1915, the year he wrote his iconic hit that heralded the era of novelty piano, Nola, named after his future wife, Nola Locke. (An article about Van Eps in the 1920s made the suspect claim that Nola had actually been composed as a banjo number.) However, even after having recorded and arranged several dozen piano rolls and solo records, Felix had some deterioration in the control of his hands, making his live performances less consistent. He was still able to compose and arrange brilliantly, so was not at a loss for work. Arndt would meet his demise in the fall of 1918 due to the Spanish Flu pandemic.

With Arndt's issues, Frank had to find another pianist to work with the trio on a regular basis. One young man he had worked with at dances, but never recorded with, went on to a notable career in music history. However, for a variety of reasons not made known by Fred, George Gershwin did not go with him into the recording studio. He ultimately went back to a familiar name, selecting Frank Edgar Banta, the highly talented son of his first accompanist, albeit nearly eighteen years younger than himself. For the next several years, Frank and Fred were the core of the various Van Eps groups.

However, for a variety of reasons not made known by Fred, George Gershwin did not go with him into the recording studio. He ultimately went back to a familiar name, selecting Frank Edgar Banta, the highly talented son of his first accompanist, albeit nearly eighteen years younger than himself. For the next several years, Frank and Fred were the core of the various Van Eps groups.

However, for a variety of reasons not made known by Fred, George Gershwin did not go with him into the recording studio. He ultimately went back to a familiar name, selecting Frank Edgar Banta, the highly talented son of his first accompanist, albeit nearly eighteen years younger than himself. For the next several years, Frank and Fred were the core of the various Van Eps groups.

However, for a variety of reasons not made known by Fred, George Gershwin did not go with him into the recording studio. He ultimately went back to a familiar name, selecting Frank Edgar Banta, the highly talented son of his first accompanist, albeit nearly eighteen years younger than himself. For the next several years, Frank and Fred were the core of the various Van Eps groups.Dissatisfied with the drummer that Victor placed with the trio, Fred convinced a producer at the newly formed Pathé label (an American branch of the French concern Pathé Freres Compagnie) to let him try recording with saxophonist Nathan Glantz. The results were so favorable that Victor automatically got on board, and the new Fred Van Eps trio recorded many of the same pieces they had started on Pathé with Victor, Columbia and Emerson. He expanded the group at times with mallet player Joe Green on xylophone, creating the Van Eps Quartet and the Van Eps Specialty Four. Even before Arndt left the fold, Fred had recorded with a quintet, sometimes with a drummer and often with two banjos, calling it the Van Eps Banjo Orchestra. While the personnel were relatively static, different group names were sometimes used for different record labels.

Note that recording for a variety of studios was not an unusual practice, as there were three main formats during this period; the vertically cut cylinders of Edison, Indestructible and Everlasting; laterally cut discs (left and right in the groove) of Victor, Columbia and Emerson; and vertically cut discs (up and down in the groove the same as cylinders) of Pathé and Edison. The distribution networks were also different for each, so there was less competition than might be imagined. There was enough of a fan base for Van Eps to go around and generate business for several companies. Fred noted that he ultimately made records for around fifteen different concerns from 1908 into the 1920s.

As Vess Ossman had experienced a lull in recording in favor of performance during 1913 and 1914, then a short surge from 1915 to 1917 that burned out, the field opened up for Van Eps to more or less dominate banjo-centric recordings of the mid-to-late 1910s. Ossman was aware of the competition, which was less a rivalry than it was acceding to an arguably better talent, in spite of his pioneering work in the genre. Ossman cuts were popular enough, however, that they warranted cover recordings by Van Eps. He noted to Walsh in 1955 that this became a lucrative period for him.

in spite of his pioneering work in the genre. Ossman cuts were popular enough, however, that they warranted cover recordings by Van Eps. He noted to Walsh in 1955 that this became a lucrative period for him.

in spite of his pioneering work in the genre. Ossman cuts were popular enough, however, that they warranted cover recordings by Van Eps. He noted to Walsh in 1955 that this became a lucrative period for him.

in spite of his pioneering work in the genre. Ossman cuts were popular enough, however, that they warranted cover recordings by Van Eps. He noted to Walsh in 1955 that this became a lucrative period for him.To some extent, it was because of accidents happening to the original masters or defects appearing in the matrices. Then, too, as time went on the methods by which Ossman had recorded became outmoded. However, the records were still popular, and Victor wanted them remade by the latest processes. But since Ossman wasn't readily available and his playing no longer was what it had been, they had me do the remakes, usually with young Frank [E.] Banta at the piano.

The majority of recording done by Van Eps and his groups into the 1920s was accomplished in New Jersey or New York, but a handful sessions were held in Montreal, Canada, for the British Victor affiliate HMV [His Master's Voice] in 1919 and 1920. Some of the Pathé discs had "Made in France" stamped on them, but that was due to the New York branch having their masters duplicated in Paris until their New York plant was ready for business.

The Victor Artists

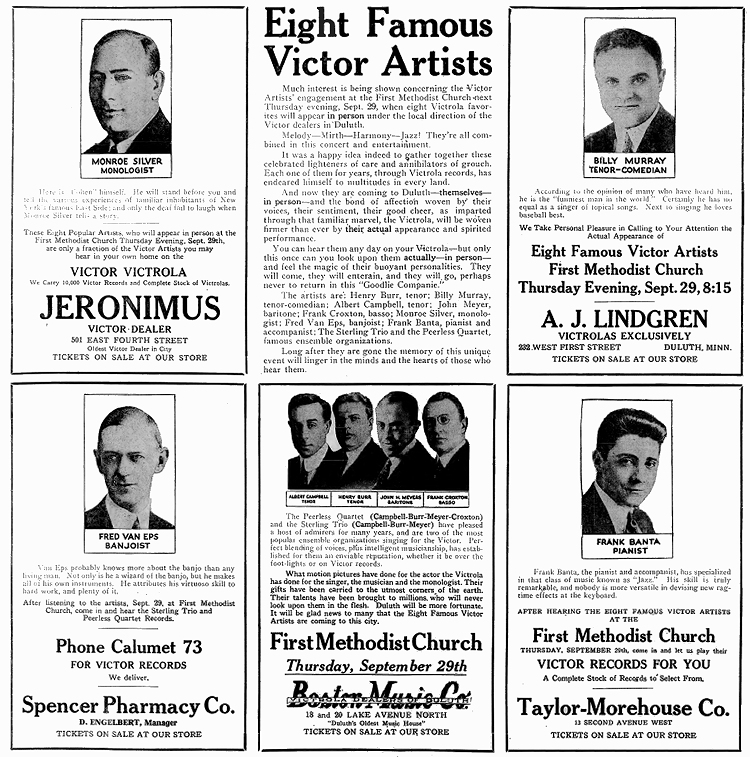

In 1915 singer Henry Burr (Harry H. McClaskey) helped to put together a power group of their top recording artists from the Victor other record companies, sending them on an annual tour around the United States to present concerts in a variety of venues, all to promote their records. They even played records at some of the presentations to show how clean and clear they were, such demonstrations being common amongst both recording companies and phonograph manufacturers. For the first two seasons of the tour the star banjo attraction was Vess Ossman. However, in 1917, he not only quit recording altogether (according to some sources being either threatened by or tired of being compared to Van Eps), but owing to "creative differences" with the group's leader and manager Burr, quit the group as well. Van Eps was asked to replace Ossman almost immediately in May of 1917, and thus began his run with "The Record Makers" or the "Eight Famous Record Artists," two of the many names given the touring group.

Among the participating artists, of which there only a couple of minor rotations from 1917 through 1922, was manager Henry Burr; singer Billy Murray, whose popularity on disc rivaled and at times eclipsed that of Al Jolson; singer Albert Campbell (a.k.a. Frank Howard) from the famous Peerless Quartet; singer John H. Meyer, who with Campbell had been a part of the Sterling Trio;

basso singer Frank Croxton, also a part of the Peerless Quartet; Jewish comedian and monologist Monroe Silver; and, at Van Eps insistence, Frank E. Banta, who was now coming into his own as a gifted performer and composer. He replaced composer/pianist Theodore Morse, who was, according to Fred, "was a swell fellow and one of the greatest writers of popular songs this country has known, but he simply couldn't play the piano the way Frank Banta could." The group was heavily advertised wherever they went, and their performances well-attended. At prices from .50 cents to $2.00 per seat, they were also affordable and accessible to most of the public. By 1920, when they all had contracts with Victor, they became Victor's "Eight Famous Phonograph Artists." The tours, which included stints in Canada where Van Eps recorded on HMV, were typically three to four months each spring into the early summer.

|

Differences with the sometimes volatile Burr appeared to be commonplace during the group's history, as the comedy singing team of Arthur Collins and Byron Harlan were among those who also left the troupe due to constant bickering with the leader. But for a time, Van Eps got along well during his travels, noting that they usually had first-class accommodations wherever they went, and made sure they were always well-dressed. At one point, Fred was accidentally handed a check for the group's take for a performance, and found the number to be at least double what he would have expected, even accounting for Murray being the top-paid artist in the group. He and some of his peers decided to comically strike on the boss, storming him with fake beards like anarchists. The joke continued for some time, and they formed their own internal group, the Order of Beards.

The 1920 census caught Van Eps in Plainfield, New Jersey, residing once more with his parents. He was clearly separated from his wife and sons, who had been living on Long Island since the mid-1910s. They both showed as still married, so Fred was clearly not yet with his second wife Florence, in spite of a later accounting of his time line. Much as Vess L. Ossman's son had continued on in his father's name as his own, especially after the senior Ossman's death in 1923, and with little separation except for dropping the middle initial, Fred, Jr., would also be known as a capable performer, but more so as a cornetist than any other instrument. His other sons all enjoyed some measure of fame. Several advertisements were placed in Freeport newspapers in the early-to-mid 1920s touting the Van Eps Brothers' Orchestra, with Robert (15) at the piano and Fred (17) on the cornet. Before the decade was out, George would be playing guitar and banjo with several orchestras, and John would take up the saxophone.

In spite of issues with the prickly Burr, Van Eps decided to go into business with him around 1921, forming the Van Eps-Burr Corporation, with the intent of building and marketing the Van Eps Recording Banjo, modeled after his own favorite instrument. Instead of the more common steel back, it had an aluminum resonator and a sound hole in the calfskin head, giving it sufficient volume in spite of his practice of finger picking the strings instead of using ivory or steel picks. After a year or so of great success, Burr and Van Eps began to butt heads concerning their respective roles in the company and the handling of finances. By July of 1922, Fred left the Victor Eight to pursue other leads, including the growing of his banjo business. The official statement to the world through the July, 1922 issue of Talking Machine World was that an increasing level of engagements in New York City kept Fred from touring with the group any longer. He was replaced by saxophonist Rudy Wiedoeft, and the touring group continued until 1928, when they finally disbanded, having served their purpose for more than a decade. For Fred, however, he was already forging ahead on his own. Frank Banta had also chosen to stay with Burr, which nearly terminated his professional relationship with the mentor who had given him his big break, although they did record a few more tracks into 1923.

The Banjo is Dead - Long Live the Banjo

It was around 1922 when Fred married Florence "Flossie" Schoffstall, with whom he remained until her death. By that time, after Fred had left the tour, he was done working for most of the record labels, including Victor, OKeh and Columbia, and made only a few more discs for Edison, Pathé and Emerson.

One of the issues that faced recording engineers to that time was the limited frequency range that the recording horn could capture, or that the playback horn could reproduce. There remains to this day, however, the element of a startling presence when hearing what is essentially a direct-to-disc performance from an acoustically-cut record, which is not altered by electronic components in any way. In this, tenors, trumpets and banjos seemed to have the best chance for adequate tone on the older players, particularly the vertically cut Pathé and Edison records.

|

This changed in 1925, both for better and worse, when electronic recording through a microphone and reproduction through amplified loudspeakers spread throughout the industry. Part of the sound of the 1920s had been driven by tubas taking the bass parts and banjos taking the rhythms. While they were still present, particularly in film scores, into the early 1930s, the ability to better capture and reproduce the much richer piano put the banjo out of favor within a few years. Fred's last recordings for Edison were made in 1926, and then, aside from radio, he took a nearly 30-year break from the studios. He experienced a personal blow that year when both of his parents died with twelve days of each other, after having lived together for so many decades. That stayed with him for the rest of his days. As the Great Depression set in around 1931, it became clear that the loud but joyous banjo was not an appropriate instrument to echo the blues-tinged feeling of the country.

During the mid-to-late 1920s, Fred took the helm of his Van Eps Banjo firm. Changes had to be made to his design, as the type of head he had been using in order to obtain extra volume was no longer necessary with microphones. So he went to a solid head design to complement the amplification. The business lasted until around 1930. The 1930 census showed Fred and Flossie residing in Fanwood, New Jersey, a neighborhood adjoining Plainfield, and Fred was listed as a musician, not as a manufacturer. Most of his gigs from the late 1920s into the 1930s were on radio in New York City, and even those were starting to wane due to a shift in popularity to piano-based music and the transition to swing. To fill in the gaps, Van Eps gave banjo lessons for a while, but the demand for that dropped to virtually nothing as well. He had been working on new techniques to finger the banjo, and was able to find one that allowed him to playas many as 14 individual notes per second. Some of his techniques are still in used decades later, but largely after the comeback of the instrument in the 1950s. He remained active in his life, however, and in 1935 penned an article about what he considered to be "America's Own" indigenous instrument, published in Hobbies magazines in the spring of 1935. There were several interesting revelations found within his essay:

...The earliest form of musical instrument was a tree stump hollowed out, with a vibrating string stretched across the top. If you sawed this off and put a handle on you would have a sort of banjo. Almost from man's first attempt to build an instrument, banjo-shaped affairs were used.

The banjo has been associated with the Negro, and while it is true that the slaves brought it from Africa in the form of the "banya," it took an Irishman, Joe Sweeney, to put it in its present form with its five strings and rim...

...Since the symphony orchestra is supposed to contain all musical colors, the time is not far distant when the banjo will be a part of these organizations. You can't get that certain timbre without the combination of catgut and calf skin... [The author would comment on this probability some eight decades out, but probably does not need to.]

...The banjo has been crossed with other fretted instruments. If you put a mandolin neck and strings on a banjo body, it becomes a banjo-mandolin. If you reverse the process and put a banjo neck and strings on a mandolin body it becomes a mandolin-banjo. In 1898 there appeared an automatic banjo housed in a glass case and operated with a perforated paper roll which controlled buttons for stopping the strings a vacuum bellows which operated still picks. This was a popular piece of saloon furniture.

...An extremely odd thing about the professional banjo players was their jealousy — not ordinary professional jealousy, but an ACUTE variety. If you were an advanced student and paid for tuition you would not be shown anything if there was danger of your becoming too good. During the first days of the phonograph the banjo was about the only instrument that recorded well and was used extensively. Violin records were out of the question — the sound went in so sweetly and came out so sour!

[Note that the following is mildly offensive, but is an exact quote by Van Eps] ...Practically everyone knows that the Stars and Stripes is our national emblem. Almost every moron knows the goldenrod is our national flower, but if you were to walk up the street and asked the first six men you met what our national instrument is you would probably get little information. If, after you told them what it is you asked what a banjo really is, you would be apt to get much less information.

Now less viable as a working musician, even though his sons were all succeeding in that field on different instruments and in different disciplines, Fred decided to put his life experience to work in other fields.

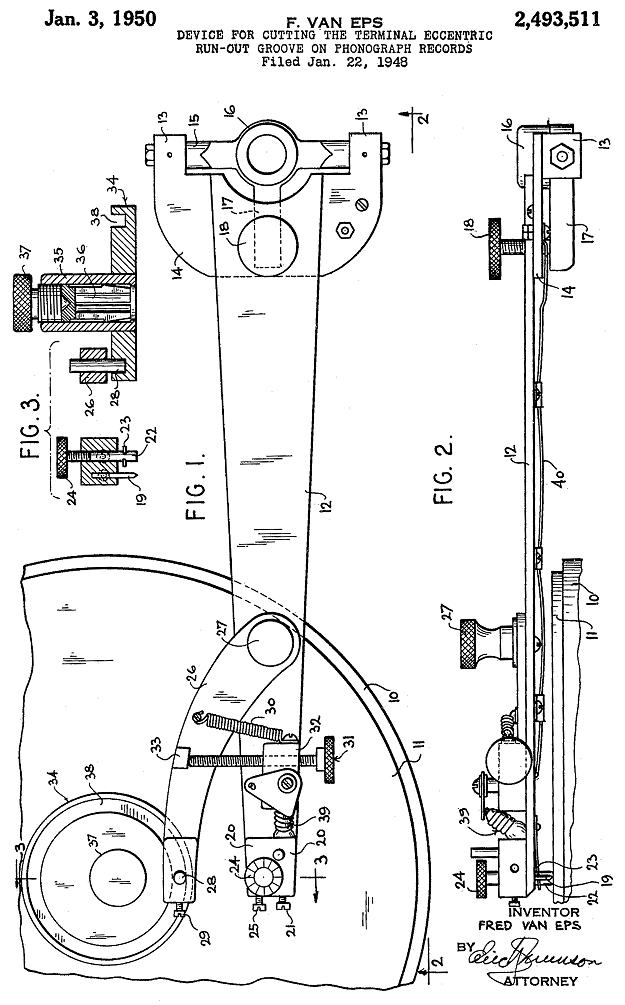

To that end he established his own laboratory near Plainfield around 1940. The 1940 enumeration taken in Fanwood showed his business as a sound recording service. Since he had first laid down recordings on his cylinder machine in the early 1890s, Fred had been fascinated by the process, and started to pursue advanced recording techniques. One of those was a vacuum system for record cutting lathes that was able to more completely suck off the threads and chips that were created by the cutting head as it laid the groove into the acetate master. He made it both efficient and quiet, as in the time before recording tape, the cutting lathe was usually just on the other side of the glass from the artists, and most records were done directly to disc. He also created a new method for cutting the ecentric inner groove of a disc that was used to activate automatic record changers. Both devices were adapted by the recording industry, and his patents made him very wealthy during the 1940s. Van Eps also created some new optic processes that allowed for special photographic effects which could be used both for art and cinema. He later noted that his laboratory business "has been a great success, and I've made most of my money in it. Luckily, I've done so well that if I should live to be 108 I'll still have more money than I'm likely to spend."

|

Thanks largely to the efforts of trumpeter Lu Watters and pianist Wally Rose in San Francisco, traditional jazz and ragtime made a comeback. Just months after the untimely 1941 death of pianist Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton in Los Angeles, they started making high-fidelity recordings of works originally recorded acoustically by Joseph "King" Oliver and Louis Armstrong in the early 1920s. Unfortunately, World War II intervened, and they had to settle for radio until 1946, when they finally assembled an early album of traditional jazz and ragtime piano pieces, the banjo being prevalent throughout. With the surprise hit of 1948 being an intended-for-radio recording of 12th Street Rag by the band of Pee Wee Hunt, ragtime and traditional jazz were both poised for comebacks. Once Capitol Records A&R director and pianist Lou Busch started producing albums of ragtime, labeled as Honky-Tonk, in 1950, followed by a group of Disney animators and professional musicians working as the Firehouse Five Plus Two at the same time, a full-fledged revival fueled by public interest and record sales was underway.

Fred was quite aware of this, and in 1952 laid down an album of his own on his self-produced Five String Banjo label, playing some tracks from his past, but using his new techniques. He was accompanied by his son Robert at that piano. Among the tracks were Ragtime Oriole, Maple Leaf Rag, Nola, The Smiler, Dell Oro, and Bolero by Moritz Moszowski (not the more famous Ravel composition). It did moderately well for a limited release, and is difficult to find in the 21st century. When asked his opinion on popular music of the mid-1950s, Fred managed an answer that historically should sound familiar when coming from any older musician, particularly a cranky 76-year-old, reflecting back on the evolution - or de-evolution - of music:

...I tune in "Hit Parade" programs and that sort of thing and listen as long as I can stand it, but I usually wind up turning the knob violently to shut the set off and muttering to myself. Popular music today is the worst in American history. When the disc jockeys play the so-called ten most popular songs of the week they select almost entirely the moronic junk picked by teen-agers who will fall for any new fad. This "rock and roll" and all that sort of rubbish is terrible beyond belief. In the old days music was for the whole family, but it was usually the grown-ups who did the buying. Nowadays it's the kids who bring home the records and tune in the radio and tv — and it's largely they who make eating in a restaurant a nightmare for a civilized person by dropping coins into juke boxes.

Flossie Van Eps had spent much of her life with a fascination for England, studying its history and customs. So in April of 1954, Fred took her on a trip to the United Kingdom. They had some issue in getting passports as Fred's birth certificate only had "boy" on it as his name, but an early recital program proved his age and existence with some extra effort. They sailed on the Queen Elizabeth, and spent nine weeks abroad, touring England and Scotland with a brief interruption for two of the weeks on the European continent. Still somewhat of a celebrity in the UK, Fred was invited to a number of private parties, and enjoyed some measure of recognition for his banjo work of the 1910s and 1920s. He even got a tour of Windsor Castle. The British magazine B.M.G. gave special tribute to Flossie, citing her charm and grace and "pleased to meet you" attitude as a great example of the "Hands Across the Sea" spirit.

They had some issue in getting passports as Fred's birth certificate only had "boy" on it as his name, but an early recital program proved his age and existence with some extra effort. They sailed on the Queen Elizabeth, and spent nine weeks abroad, touring England and Scotland with a brief interruption for two of the weeks on the European continent. Still somewhat of a celebrity in the UK, Fred was invited to a number of private parties, and enjoyed some measure of recognition for his banjo work of the 1910s and 1920s. He even got a tour of Windsor Castle. The British magazine B.M.G. gave special tribute to Flossie, citing her charm and grace and "pleased to meet you" attitude as a great example of the "Hands Across the Sea" spirit.

They had some issue in getting passports as Fred's birth certificate only had "boy" on it as his name, but an early recital program proved his age and existence with some extra effort. They sailed on the Queen Elizabeth, and spent nine weeks abroad, touring England and Scotland with a brief interruption for two of the weeks on the European continent. Still somewhat of a celebrity in the UK, Fred was invited to a number of private parties, and enjoyed some measure of recognition for his banjo work of the 1910s and 1920s. He even got a tour of Windsor Castle. The British magazine B.M.G. gave special tribute to Flossie, citing her charm and grace and "pleased to meet you" attitude as a great example of the "Hands Across the Sea" spirit.

They had some issue in getting passports as Fred's birth certificate only had "boy" on it as his name, but an early recital program proved his age and existence with some extra effort. They sailed on the Queen Elizabeth, and spent nine weeks abroad, touring England and Scotland with a brief interruption for two of the weeks on the European continent. Still somewhat of a celebrity in the UK, Fred was invited to a number of private parties, and enjoyed some measure of recognition for his banjo work of the 1910s and 1920s. He even got a tour of Windsor Castle. The British magazine B.M.G. gave special tribute to Flossie, citing her charm and grace and "pleased to meet you" attitude as a great example of the "Hands Across the Sea" spirit.The Van Eps returned on the Queen Mary in early June, and spent an evening with some New Jersey friends who had picked them up from the ship. As Van Eps told Walsh over a year later, "We went into our home. Flossie sat down, said 'Our trip was the most wonderful experience of my life, but it's good to be back' — and was dead within just a few minutes. It seems that her strength held together just long enough for her to take the trip she had dreamed of all her life." She had died literally within an hour of her arrival home from a long-standing heart ailment. Fred was nearly inconsolable for several weeks, but chose to resume an active life in her honor before the year was out.

Shortly after the 1955 interview with Walsh, Fred moved to Burbank, California, to be near a his sons Robert and George who had been working in the film industry as composers, arrangers and musicians. Fred, Jr., who had worked with Paul Whiteman as an arranger in 1930s, was then working on Raymond Scott's television show Hit Parade. John had been killed in an automobile accident in 1945, which had given Fred a view of life as a precious commodity to be lived to its fullest, underscored by Flossie's death. He spent his last few years with them, experimenting with recordings, telling tales of his life and friends, and sometimes pulling out the banjo to play the old tunes. One of his late quotes from the 1955 article, in which he hoped to live to 108 and beyond, and which he attributed to his old boss Thomas Edison, was, "I'd rather wear out than rust out." Fred Van Eps died in late 1960 just short of age 82, just after having taken a driving test at the DMV office. His son George told the press that he was probably very excited by the test, and the strain on his system simply took him to his death. He left behind a legacy of recordings, stories, inventions, and three talented sons who continued to make their mark in music for the next three decades.

More than half of the information on the life of Fred Van Eps was pulled from a remarkable multi-part interview by Jim Walsh in Hobbies Magazine published from January through April, 1956, and viewable at this linked page. Confirmation or corrections on some points were applied through the remaining information discovered by the author, which was found in public records, newspapers, magazines, and record company logs and discographies.

Recordings on Edison Cylinders

Recordings on Edison Cylinders  Recordings on Victor

Recordings on Victor