Vess Ossman, though not a composer of ragtime, was one of its earliest white proponents who helped to spread it around the United States through his performances and popular recordings. He was born in Hyde Park, New York, to German immigrant Frederick Ossman and his Irish bride Anna Hindsley, and was the third of five children, including Augustus (1865), Annie (1866), Ellen (1871) and Elizabeth (1875). The 1870 and 1880 Federal censuses along with the 1875 New York State census all showed Frederick working as a baker in nearby Hudson. During his childhood, which included some basic music lessons, Sylvester, who eventually took on the unique nickname reduction of Vess, took a shine to either the four string or five string plectrum banjo at around age twelve, actually constructing one of his own out of a peck measuring device. Interested in learning all he could about manipulating strings, Vess took lessons from violinist Fidell Wise, during which time he learned more about fingerings and tunings. He soon developed some of his own unique techniques for playing the instrument, playing both styles, but doing much of his work on five string instruments.

As he became more of a virtuoso in his mid-to-late teens, Vess widened his repertoire to virtually any form of music he came across, from Chopin to Stephen Foster. He started to win awards in several contests he had entered, and before he was twenty was an acknowledged champion of banjo playing. One typical review of his performance skills was found in the Hudson Republican of September 22, 1887:

Vess Ossman, the champion banjoist, held forth with H.T. Rider's orchestra. The Professor had the audience spell bound. That forty dollar Dobson banjo in Vess's hands just catches them.

By the late 1880s there were several mentions of him in the Chatham [New York] Republican, not only telling of his prowess at the instrument, but noting that he was working as an instructor in banjo playing in Hudson and other Hudson River Valley towns. He also ventured to New York City in early 1888 for an appearance at the first annual United States Banjo Contest held at Chickering Hall, as noted in the New York Evening Telegram of February 28, 1888:

Chickering Hall was packed last evening with an audience of cultured people, who came to hear the twanging of banjos for two hours at the banjo tournament organized by Messrs. [theater managers Charles E.] Phipps and [James V.] Gottschalk. There was plenty of enthusiasm, and the audience was unsparing in applause. Among the well-known players were "Ruby" Brooks, R.W. Brailsford, H.N. Denton and Vess Ossman. The Columbia College Banjo Club was present to play against any other college boys, but they were the only collegiate banjoists present, and collared the prize by default. Ruby Brooks won first prize in general contest and Mr. Ossman the second. A general concert followed.

In January of 1890 Vess ventured to Poughkeepsie, New York, for a contest against his rival Ruby Brooks, taking a prize of $500 and the title of Banjo Champion of America. Then two months later, at just 21, he married 15-year-old Eunice Annie Smith in Manhattan, New York, in March of 1890. The circumstances of the event were not known for sure, but it appears that she had either a miscarriage or lost a child within the next year or so. The couple would ultimately lose four of eight children born to them over the next eighteen years.

Leaving his home town behind in the early 1890s, Ossman ventured southeast to a permanent presence New York City just as the first stirrings of what would become ragtime were being performed, usually by musicians for each other.

In 1891, he finally took the gold medal at the United States Banjo Contest held at Chickering Hall in New York. That same year had him playing solo concerts at several events throughout the city. The following year, in 1892, Vess became a member of the Dunham Quartette, a vaudeville act comprised of banjo, piano, a vocalist, and a humorist. However, it soon became clear that his virtuoso performances warranted him working as a solo act, accompanied at times by a piano, so much of his career was spent giving concerts with the occasional singer. He was easily able to hold an audience in a venue as large as the Madison Square Garden concert hall, where more than one review of the mid-1890s made it clear that he was "rapturously received." Ossman's son Sylvester Louis, Jr., was born in February of 1893.

|

From 1893 to 1896, Ossman continued to win gold medals at various contests, and quickly became a favorite performer everywhere he went. He traveled on vaudeville circuits throughout the Northeast and occasionally into the Midwest, sometimes getting the coveted spot of next-to-last on the show, usually reserved for the most popular entertainers. His playing style was unique among many banjoists. Some treated it as an accompaniment instrument, quickly strumming while changing chords underneath a melodic line, which made for a good show, but could wear on the listener after a while. Vess had his own technique, now referred to as "classical banjo style," where he finger-picked virtually everything in the same manner as a classical guitarist. Instead of steel strings, he preferred using gut, which was what most banjos used into the early 20th century, and they were plucked with his fingers rather than with a pick or plectrum. They did not have quite the same volume as steel, but with a higher resonance on a properly-tuned and calibrated banjo head, every pluck could be heard at the back of most concert halls, even the cavernous Madison Square Garden. His prowess at an instrument with such bright tone and clarity would soon reap benefits and increase his world-wide fame.

When Thomas Edison first invented what would become known as the phonograph, his intention was that it would be an ideal instrument for dictation and the capture of oration. Similar inventors, including Alexander Graham Bell, saw it as a means for capturing telephone conversations or even telegraphy. Edison eschewed the idea that his invention should be used for the reproduction of music. However, other inventors sought to improve the acoustical capture and playback properties of phonographs, and by the mid-1890s both Berliner flat discs and Columbia cylinders were being sold to the public with the idea that they could bring great performances into their homes. Both formats had inherent flaws. Cylinders retained a constant speed for either two or four minutes (depending on how the machine was geared), but until around 1902 or so could not be produced in mass, requiring performers to cut ten or so at a time in a day-long session of dozens of performances of the same piece. Those in turn could be copied via a tube to more cylinders, but with a significant loss in fidelity. As for the Berliner-style records, as the needle got closer to the center of the disc the rate of speed through the groove was significantly reduced, changing the fidelity. However, they were easy to reproduce from a single master, allowing for tens of thousands of copies of a single performance.

Both, however, were not all that friendly to instruments like the guitar, double bass, or piano, as early recording horns and studio techniques simply could not capture the full breadth or nuances of these instruments.

|

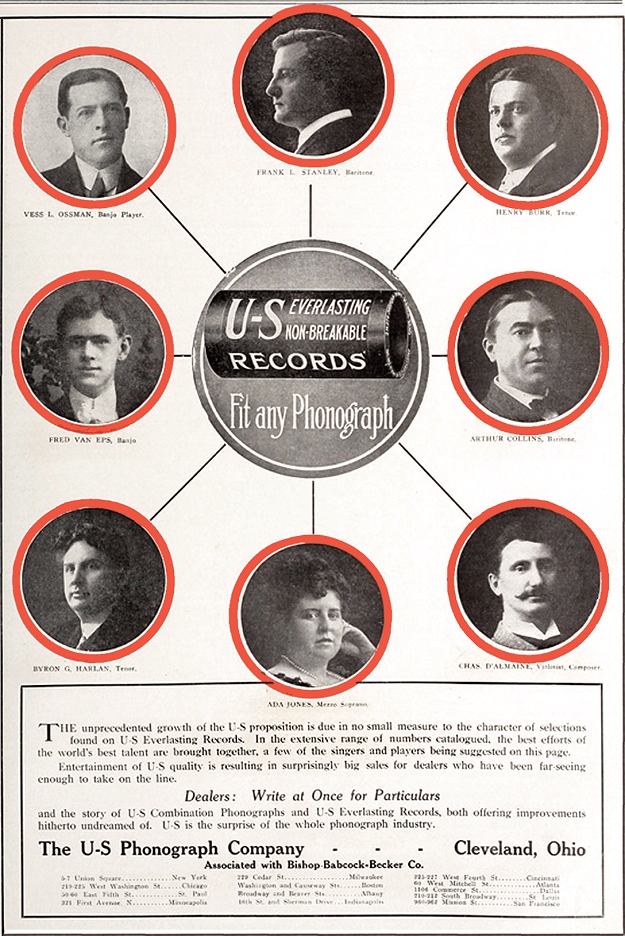

When record companies started looking for material for the public to take home with them, vocalists were at the top of the list, usually with a small but loud ensemble. However, for instrumental pieces of popular songs, the banjo had a clear advantage over other instruments in the late 1890s, as it was not only easy to capture by most recording horns, but would carry further on the average playback horn as well. This property, a knowledge of current popular works, and a name that the public knew, made Vess Ossman and his peers valuable commodities in the mid-to-late-1890s. A little late to the game, Edison started issuing music discs in 1896. Although Edison himself was not a big proponent of popular music, he eventually put others in charge of the recording end of his enterprise, stipulating that fine classical works would always be available on his label.

Having first recorded a solo of John Philip Sousa's Washington Post March to North American Phonograph Company cylinder in 1893, and several more pieces into 1894, by late 1895 Ossman was often engaged in the demonstration of phonographs. This was usually an event in which an artist actually recorded something live on stage to a clean disc, then that disc was played back on an expensive phonograph in an effort to amaze the crowd, and, of course, sell phonographs. It was not long before Ossman started recording discs for the Berliner Company. His 1897 disc of a Ragtime Medley is considered to be the first ragtime-styled commercial recording. While Ossman would record several cylinders for Edison and Columbia over the next decade, a number of these would be done in 1902 or later, once the methodology had been perfected for mass reproduction of that media. The necessity of playing the same banjo solo fifty times in a day to reproduce 500 cylinders was simply not a appealing option. Given the tone of his instrument, the reproduction in the inner grooves of a disc were less of a problem than for many other instruments or certain timbres of voices. It also was part of why he was used for live stage demonstrations, of which one was described in the November 26, 1898 edition of the Music Trade Review:

On the afternoon of Nov. 23d, a private exhibition was give by the American Graphophone Co. to a few newspaper men and scientists in the Bowling Green Building. A new [G]raphophone [cylinder] grand, a marvelous invention, which embodies a new discovery in acoustics, was the reason for the assembling...

First the exhibitor gave a test of an ordinary phonograph. It was followed immediately by the grand. The qualities of this new instrument are marvelous. With the [G]raphophone [G]rand it is possible to fill the Metropolitan Opera House or the Madison Square Garden... One hundred feet away from the horn the tunes were marvelously distinct, though the acoustic properties of the room were not favorable for the transmission of sound...

A record was made before the audience, Vess L. Ossman, the well-known banjoist, making the record which was afterward reproduced, and it was almost impossible to distinguish the real player's effect and that made by the reproduction at the [G]raphaphoe [G]rand... The exhibition was given to thoroughly establish in the minds of those interested in the art what a phenomenal advance has been made in the development of sound reproduction.

From 1896 to 1899, the majority of Ossman's recordings were of his solo banjo playing. The repertoire consisted largely of popular tunes of the day, which included some of the first recordings of ragtime pieces weeks after they were first published. Stirring marches were also popular, as were pieces of Americana. As his records grew in popularity, Vess would record with a pianist, accompany a vocalist (primarily baritone Len Spencer in the beginning), and eventually fronted bands for marches. While his earliest recordings were primarily for Berliner and Edison, Ossman did not have an exclusive contract, and was soon heard on Columbia cylinders and discs. Publishers often sent him advance copies of what they felt would be a future hit, and touted his recording of a piece in their advertising for that work. By 1900, his name was quite well-known, and he was making allegedly black-originated ragtime [which is actually a more complex combination of influences] more palatable to white audiences.

The 1900 census, taken in Manhattan, showed Vess and Eunice with Vess, Jr., and their next surviving son, Raymond (1/1899). (Three other children had died at birth or in infancy during the 1890s.) Ossman was listed in that record as a banjoist.

|

In mid-1900, shortly after Victor Records of Camden, New Jersey, had been established, that management for that label started signing on top artists. With the combination of their low-cost mass-produced phonographs, good music content on their house brand, and a wide distribution network, Victor quickly became one of the top record companies of the country, competing largely with Columbia in the disc sector of the market, having chosen to not create cylinders. Columbia had gained an edge over Edison in the cylinder market owing to a similar paradigm of good distribution and fine music content. For Victor, Ossman re-recorded many of his previous pieces done for Berliner and Edison, and at that, even in multiple formats. Records in the form of 7" discs had just over a two minute play time, while around three and a half minutes could be rendered on a 10" disc, and even an additional minute on a 12" record. So many of the Ossman's recordings from 1900 to 1904 could be heard in two or three different renditions, and at that, he even re-recorded some of his Victor material as new masters became necessary to keep up with sales. Some of the same material was recorded on other labels as well, but with different arrangements or configurations.

Ossman's celebrity as a banjoist was enough to warrant the creation of a special banjo manufactured under his name. The Ossman Special Banjo was advertised in the trades for $75.00 in 1901. Bolstered by his recordings and a demand for more of the new American ragtime music and cakewalks, Ossman's reputation had spread internationally, so in the late spring of 1900 he went on his first overseas tour to England and Paris, opening at St. James Hall in London on May 10. While in London he did some additional recordings for Columbia Records. A second British and European tour was launched in 1903, which included even more Columbia Records recording dates in London. While there, he played his favorite White Ladye banjo for the King, as described in an endorsement letter published in the Music Trade Review of September 19, 1903:

Isle of Wight, England, August 5, 1903.

This is the place where they hold the great regatta. The King is here all week, and last night I played for him at the "Royal Squadron" — the most exclusive club in the world. The Prince of Wales was also there, besides all the royalty you ever read about, and you can safely say that never was a banjo played for so many of the nobility at one time. I am not the only American, but I am the only banjoist who ever played at the "Royal Squadron."

I used your "Whyte Ladye" banjo. There is a yacht lying outside in the bay called "Whyte Ladye." People looked at the banjo and expressed their delight at its beauty, and when they saw the name they wanted to know if there was any connection between the two. [A note after the article confirmed that the banjo was indeed named after that particular yacht.]

Have had a wonderful trip, and have done my best to make the banjo popular. Am coming home next week to get ready for the season, etc. Getting before the King is worth more to the young American banjoist than all the classical music could ever do. I have made a reputation I am proud of — one which will always live among banjoists — and I made it on popular music.

Wishing you success, I am, Sincerely, VESS L. OSSMAN

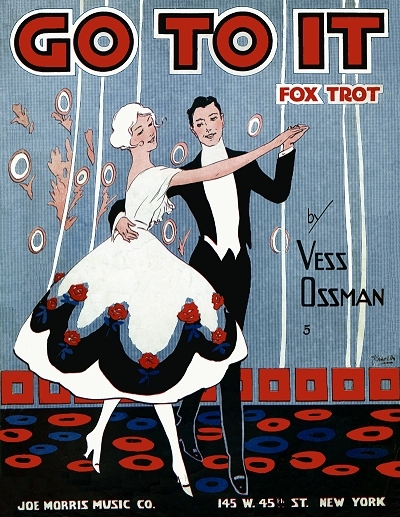

It is interesting to note that Vess was quite clear that his fame was built on interpreting the newer popular music, which was largely based on ragtime rhythms, as much as the classics. Up to that time the old saws of Stephen Foster had been the most played works among white banjoists. Ossman's fame had actually led to a rising popularity in the banjo during the late 1890s and into the early 1910s, both among black and white performers. Many plucked string ensembles to that time were made up of guitars and mandolins, but there was a proliferation of banjo ensembles as well, some of the touring in vaudeville, but many more of them local organizations found in small towns throughout the United States. Mandolin and banjo clubs were prominent during this time, and many of them were actually featured on the covers of sheet music, usually vanity publications. In spite of this, Ossman appears to have not garnered such attention, as it was difficult to find any sheet music covers with his visage, in spite of his publicized titles as either the "King" or "Czar of the Banjo."

Together with Audley F. Dudley (6/1880 to 9/4/1916) on mandolin and mandolin-banjo, and his older brother George Nabb Dudley (4/24/1875 to 4/28/1963) on a remarkable custom-built 36-string harp guitar (possibly substituted for on some dates by Roy Butin on a similar 24-string instrument), he formed in the Ossman-Dudley Trio which became somewhat of a sensation. The Dudley brothers also had similar groups on the side, but they were present on a number of Ossman's Victor, Columbia and Edison discs. As gifted as Ossman was with his banjo, George Dudley's command of the double-necked double-strung harp guitar added a richness and texture that was unusual for early acoustically rendered recordings.

he formed in the Ossman-Dudley Trio which became somewhat of a sensation. The Dudley brothers also had similar groups on the side, but they were present on a number of Ossman's Victor, Columbia and Edison discs. As gifted as Ossman was with his banjo, George Dudley's command of the double-necked double-strung harp guitar added a richness and texture that was unusual for early acoustically rendered recordings.

he formed in the Ossman-Dudley Trio which became somewhat of a sensation. The Dudley brothers also had similar groups on the side, but they were present on a number of Ossman's Victor, Columbia and Edison discs. As gifted as Ossman was with his banjo, George Dudley's command of the double-necked double-strung harp guitar added a richness and texture that was unusual for early acoustically rendered recordings.

he formed in the Ossman-Dudley Trio which became somewhat of a sensation. The Dudley brothers also had similar groups on the side, but they were present on a number of Ossman's Victor, Columbia and Edison discs. As gifted as Ossman was with his banjo, George Dudley's command of the double-necked double-strung harp guitar added a richness and texture that was unusual for early acoustically rendered recordings.What Ossman was not aware of during this period of personal popularity was that he had a shadow which would eventually overtake him. Frederick Fletcher Van Eps was born in Somerville, New Jersey, in 1878, more than ten years after Vess. As a teen he became interested in the banjo, and his model for how to approach arrangements soon became Ossman. Fred listened incessantly to Ossman's North American Phonograph and Edison cylinders, trying to emulate his style of playing. He also recorded his own takes of the material to see how it would sound. In 1897 when he was around 18, Van Eps went to the Edison recording studio in East Orange, New Jersey, and secured a job based on his banjo playing and knowledge of the recording technology. Each Wednesday he recorded popular songs for $1 per cylinder, which was a decent wage at that time. One of his first accompanists was Edison staff pianist Frank P. Banta, father of future novelty piano composer Frank Edgar Banta, who had also worked with Vess. While Ossman was returning from his second European engagement, Van Eps was recreating some of his idol's performances for Edison and Columbia, while infusing his own particular originality. At times, when Ossman masters were worn out, Van Eps would re-record them nearly identically, enough that they were sometimes issued using the same catalog number as the original.

In 1903 and 1904 Vess did a vaudeville tour with fellow banjoist Parke Hunter, and had a performance residency for a while at the Metropolitan Hotel on Broadway in Manhattan. The 1905 New York State census taken in Manhattan showed him employed as a musician, and that he and Eunice had added a daughter to their family, Euphemia "Effie", born in 1902. Over the next couple of years, the Ossmans moved across the Hudson to Palisades Park, New Jersey. From 1905 forward, his recording sessions with all labels were less frequent, and by 1910 they would dissipate to nearly nothing. However, some of his most enduring work was also done then, particularly in 1906 and 1907 with recordings of Scott Joplin's Maple Leaf Rag, Tom Turpin's Buffalo Rag and St. Louis Rag, and the controversial but popular St. Louis Tickle by Theron C. Bennett.

As Ossman's star began to fade in 1908 and later, the younger Van Eps was building a following and getting more material on disc, much of it his own, although there were still the occasional cover sessions to recreate Ossman cuts. In late 1910, Fred was able to secure a position recording for Victor as well.

|

The live performances continued for some time. During the 1907 summer season Ossman and his quartet (personnel not established) played at the famous Manhattan Beach Hotel on Coney Island, New York. In 1908 he did another tour with pianist George McKelvey, humorist F.J. Rice, and the inimitable singer Billy Murray. Ossman was seen playing in a number of New York and Northeast theaters in 1909 as well, always receiving a warm reception in the press when he returned to Hudson to perform. But by 1910 the larger engagements started to drop off, in part because of competition from Broadway shows, but also due to the popularity of ragtime piano. For part of 1910 Vess was playing for dinner crowds at the Kaiserhoff restaurant and small venues like the Daly Theater, where he once cause several other musicians to walk out as he was not a union member. There were also advertisements in newspapers during the summer of 1910 for Ossman's appearances with a trio at McGown's Pass Tavern in Central Park. The 1910 census taken in Palisades Park had Vess interestingly listed as both a musician and a musical agent, although if the latter was on just his own behalf remains unclear. It also revealed the addition of one more Ossman daughter, Annadele (1907), further showing that only four of the eight children born to the couple were still living, the oldest being Vess, Jr., now 17.

Vess continued to record now and then for the next two years, but appears to have stopped doing so after 1912, either due to his own reasons or because he was no longer requested. As the popularity of Fred Van Eps was on the rise during this time, it was more likely the former, but even Van Eps did not quite rise to the level of fame that his mentor-by-proxy had enjoyed in the prior decade. Vess continued to play at restaurants, cabarets, intermissions of shows, and occasionally in the pit orchestra of a show. He was also said, without solid verification by newspaper sources, to have been the first performer to introduce the banjo into church, although they had likely been in black churches throughout the south for some time.

Perhaps it was by request, or simply an effort to regain his professional footing, but in 1915 resumed his recording career, cutting sides for both Victor and Columbia. In late 1916 the announcement was made in Variety that the Victor and other record companies were sending some of their top artists on a regional tour as "The Record Makers," and later as the "Eight Famous Record Artists." Among those mentioned were Ossman, Billy Murray, Arthur Collins, and composer/performer Theodore Morse. Ossman would be a part of this annual three-to-four month tour for the next two years, performing with his own orchestra and jazz band in various venues during the same period when not on the Victor ticket. He ultimately left the touring group in May of 1917 due to disagreements and personality conflicts with fellow performer and group manager Henry Burr (Harry H. McClaskey). He was replaced nearly instantly by Fred Van Eps, and Morse was likewise supplanted by Van Eps' regular pianist, Frank E. Banta.

In spite of the Victor publicity, Ossman was still recording for Columbia. Many artists of that time were able to record for competing labels because some like Indestructible and Edison produced cylinders, some made lateral-cut (left to right) discs, and some like Edison and Pathé made vertical-cut (hill and dale groove) discs. Ossman's last sides for Columbia would be cut in mid-December of 1917. Earlier in the year, Sylvester, Jr., noted on his draft record that he was a musician at age 24. In fact, he had become quite an adept banjoist like his father, was a talented pianist, and dabbled in composition as well. He chose to go by Vess Ossman without the middle initial, using that difference to distinguish himself from his famous father, while still riding on the coattails of his highly-regarded name. The piece Go To It published in 1917 is most likely by the younger Vess Ossman rather than his father, given some of the data associated with it, but that is a probable and not definitive assertion. It would, however, better explain why no earlier compositions by the older Ossman were found between the 1890s and 1917.

Looking for a change of pace in addition to a change of venue, and reportedly to find new audiences as Van Eps was dominating the East Coast with his banjo act, Vess headed to western Ohio in 1919. The Ossman family, with the exception of Vess, Jr., were found in Dayton, Ohio, for the January 1920 census. In addition to Vess being listed as an orchestra musician, Euphemia, now 17, was also shown plying the family trade as a musician working in a hospital.

It was not uncommon during this time period for hospitals to have a musician on staff to entertain and relax patients, an early form of music therapy. His oldest son was also residing in Dayton, already married and divorced, and similarly working as a musician. Vess, Sr., was now working with his own Ossman's Singing and Playing Orchestra, a moderately-sized dance band, in Dayton as well as in Indianapolis, Indiana and other regional metropolitan areas, playing primarily in dance halls and in cinemas between reels and or for special occasions. In 1921 and 1922 there were notices for appearances by the Ossman group throughout the Midwest, including Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, and Indianapolis. Vess, Jr., who had joined with his father, and in April of 1922 he was advertising in The Billboard for a number of musicians to form a new ensemble based in that city. The younger Ossman was soon the musical director of the Miami Hotel in Dayton.

|

There seemed to be a smooth transition between father and son in the early 1920s as Vess, Jr., appeared to have taken over the title of "World's Greatest Banjo Player" under the same name, in spite of the popularity of Fred Van Eps. The younger Sylvester formed another two-banjo act initially with his father, then later with other players, which was called The Ossmans no matter who the identity of other banjoist was. In 1923, father and son took their act on the road as part of the B.F. Keith's Vaudeville circuit. Now nearing 55 as the tour started, Vess L. Ossman was no longer able to withstand the rigors of constant travel and performance. In late November at a show in Minneapolis, Minnesota, Sylvester suffered a minor heart attack. He was sent to the hospital to be checked out, then returned to the show within a couple of days. A week later while in Fairmont, Minnesota, he suffered a major heart attack just after what turned out to his last performance on stage, and died shortly afterwards. For reasons difficult to discern, Vess was not interred in Hudson, or even Dayton, but was laid to rest in Valhalla Cemetery in Saint Louis, Missouri. It is possible that the family was relocating there, as it would be the home base for his son by the mid-1920s.

Vess, Jr., continued to work throughout the 1920s, and managed to live up to his father's reputation as a banjoist, in addition to select other instruments. As the banjo lost favor with the public during the Great Depression, Vess switched to guitar for a time, and then either worked for or ran his own theatrical agency, as noted in Saint Louis directories and the 1940 enumeration. At the beginning of World War II he secured a position in a small arms plant, but managed to work there for only a few weeks. The younger Ossman did not live even as long as his father, dying in Saint Louis of coronary thrombosis fron angina on January 22, 1942, just short of his 49th year. Today, the legacy of the original Vess Ossman lives on in compilations of his early cylinders and discs, and should be highly regarded for its role in bring the originally black music form of ragtime into the homes of white music lovers everywhere, helping to create an appreciation and generate increased popularity of this unique American genre.

Recordings on North American Phonograph

Recordings on North American Phonograph  Recordings on Berliner

Recordings on Berliner