See a need and fill that need. That is what at least one young entrepreneur who knew something about the travails of self-publishing attempted to do. While there were a handful of other companies that worked in a manner similar to H. Kirkus Dugdale, his case brought notoriety due to its national scope.

Horace Kirkus Dugdale was born in Baltimore, Maryland on November 24, 1890, to Horace Cleveland Dugdale and his English bride Edith Mary Kirkus. His brother George was born on March 7, 1892. The 1900 enumeration showed the family living in Washington, DC, with Horace C. working as a caterer.

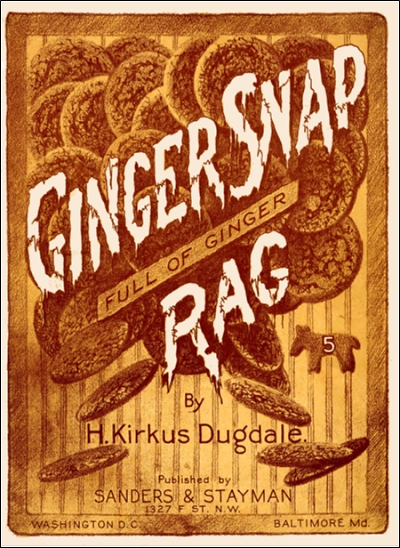

Horace K. showed musical promise and ambition as a teenager. In the fall of 1905 he started attending Business High School in Washington, and by the time he was 17 was already playing his compositions at school events. He received further training in the Virgil Clavier Piano School, from which he graduated in the summer of 1907. Horace managed to get one rag published by Sanders & Stayman (a music company doing business in both Washington and nearby Baltimore, Maryland), which was the somewhat quirky but passable Ginger Snap Rag. The 1908 and 1909 Washington city directories showed him working as a librarian, but a specific library was not listed.

He received further training in the Virgil Clavier Piano School, from which he graduated in the summer of 1907. Horace managed to get one rag published by Sanders & Stayman (a music company doing business in both Washington and nearby Baltimore, Maryland), which was the somewhat quirky but passable Ginger Snap Rag. The 1908 and 1909 Washington city directories showed him working as a librarian, but a specific library was not listed.

He received further training in the Virgil Clavier Piano School, from which he graduated in the summer of 1907. Horace managed to get one rag published by Sanders & Stayman (a music company doing business in both Washington and nearby Baltimore, Maryland), which was the somewhat quirky but passable Ginger Snap Rag. The 1908 and 1909 Washington city directories showed him working as a librarian, but a specific library was not listed.

He received further training in the Virgil Clavier Piano School, from which he graduated in the summer of 1907. Horace managed to get one rag published by Sanders & Stayman (a music company doing business in both Washington and nearby Baltimore, Maryland), which was the somewhat quirky but passable Ginger Snap Rag. The 1908 and 1909 Washington city directories showed him working as a librarian, but a specific library was not listed.In the summer of 1909 Dugdale wrote a show called The Dress Rehearsal which played for the summer at the casino in Ocean City, Maryland to some acclaim in the press. By that time, although still working as a librarian, Horace had already started his own music firm with a friend called Dugdale and Corbett which apparently specialized in music transcriptions and custom compositions, and had also copyrighted Ginger Snap Rag and his show. Horace continued to compose stage works, and appeared on stage in Washington performing his own works with an ensemble. He proudly composed the Alumni March as the official march of the Alumni Association of Business High School.

In 1910, now going as H. Kirkus Dugdale, Horace saw an opportunity to be of help to those looking to publish without overinvesting himself. Listed as a musician in the Washington, DC, city directory, he became one of a handful of entrepreneurs who had the idea that the fledging songwriter should pay to produce their own product, but that he would facilitate the process. In other words, he would act as a go-between for the composer and the printer.

Dugdale's earliest solicitations were curious to some degree, as they were done by mail to people evidently recommended to him by some other source. This caused somewhat of a laugh for New York's largest publisher at that time, no less than Jerome H. Remick, when the boss himself, who was a businessman and not a musician by any stretch, received this letter in late August 1910 at his Chicago, Illinois, manuscript department:

Washington, D. C, Aug. 22, 1910.

Mr. J. Remick, Chicago, Ill.:

Dear Friend—You have been recommended to us by one of our writers as a song writer of talent and ability, and we take pleasure in writing you to request that you submit some of your work to our manuscript department.

If available for our catalog we will be glad to arrange it for publication, composing music to your verses, or properly arranging your own music (if you are a composer), and will publish whatever work we accept on our excellent plan, paying you 50 per cent., or one-half the profits on each copy we sell.

A fortune awaits the man or woman who can write the words to a successful song or compose a successful melody, and if you have any talent whatsoever you owe it to yourself to submit your work to us, as we are able to advertise it among music buyers and musical people throughout the country. You do not have to be an expert or a professional, nor do you have to have a literary or musical education, as our experts criticize and rearrange your work thoroughly. Our excellent staff of well-known composers and arrangers is at your service.

We trust you will send us some of your work by return mail. Our criticism and frank advice are free. Very respectfully yours,

(Signed) THE H. KIRKUS DUGDALE CO.

Dictated, J. Intro.

The retort to the humorous incident from the Music Trade Review staff writer was more of a harbinger of things to come than he might have anticipated: "Needless to say, such letters, if genuine, cause endless trouble to real, professional song writers. They cause men to attempt songs who would [do] better [to] stick to the rake and the plow."

By 1911, Dugdale had added on the extra service of composing music to submitted lyrics or poems, part of a mini-music industry creating song poems. Advertisements appeared around the country under the title "SONG POEMS and Musical Compositions," asking prospective clients to write for the free particulars, and the publication was guaranteed. The terms of that guarantee were not specified in the ad, however. During that same year he was married to Margaret D. Lindale, three years his senior, in a ceremony held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

While Horace was seemingly a capable composer, at barely 21 he was running a quickly growing business, so hired other people, some evidently less capable than himself, to do the music writing. He also contracted with a local printer, Allyn B. Hayworth, to do the lion's share of the work with the engraving, cover art, printing, etc. With this infrastructure in place and allegedly a few happy customers in the wind, Horace incorporated the four-year-old company as per this notice in the Washington papers in February, 1912:

The H. Kirkus Dugdale Company, which was established four years ago for the publication and promotion of music, recently has been incorporated with nonassessable stock amounting to $250,000, under the laws of Delaware. The officers are H. Kirkus Dugdale, president; M.D. Dugdale, vice president, and M.E. De Voll, secretary-treasurer. The home office is at Fourteenth and U streets northwest.

At the U Street location, Dugdale had a building erected that on the lowest floor contained a theater of an estimated 300 to 400 seats (not specified, but based on descriptions and drawings). Above it was his two-story-high office building, which he regarded as state of the art at that time. A brochure that Dugdale released in 1913 spent a great deal of ink lauding the light and ventilation qualities of his organization, but virtually none on the quality of the output, other than the phrase: "Isn't it natural that under such fine working conditions we simply must produce our best work?"

Dugdale's was not the only firm in the country soliciting works from fledgling or, to be honest, vain or desperate composers and lyricists, but by 1913 he was certainly the most prolific of the firms, advertising in almost all of the 48 states of the union and into Canada. A typical advertisement is shown here:

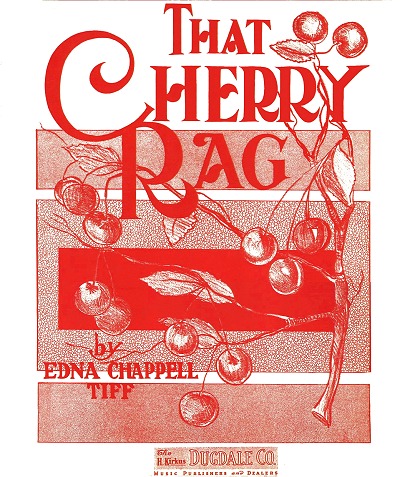

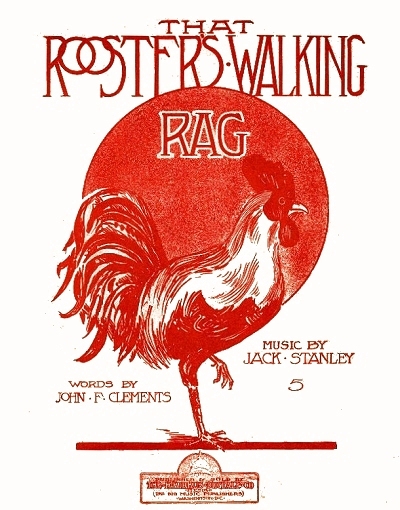

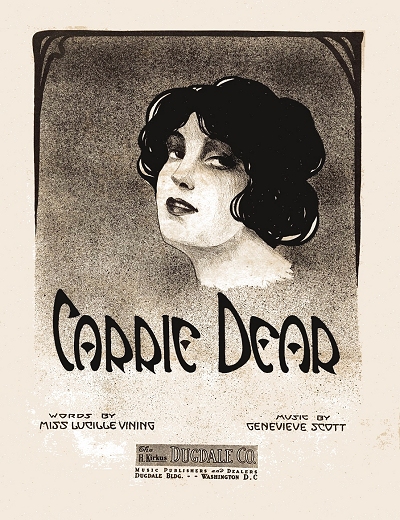

In 1912 and 1913 the company received tens of thousands of requests for information which turned into more than 1,000 contracts to either return 200 or more copies of an engraved piece, or, for a little extra, to write music to go along with a poem and return the same package. Among those female composers who took the bait were Vivian Valrie Bray of Texas, Irma Hult of Nebraska, Thelma Kay of California, Anna Lang and Pearle Liddell of Iowa, Harriet Reynolds Marchant of Virginia, M. Mae Serviss of Ontario, Canada, and, at least one minor success story, Edna Chappell Tiff of Kansas City, Missouri, with That Cherry Rag. Most of these women got what they paid for, and perhaps a little less than they should have. Their rags or other works were, for the most part, properly engraved and came with a nominally attractive original cover, a Dugdale imprint, and 200 copies with a vague promise of distribution of the rest. These were the most legitimate of the transactions.

Most of these women got what they paid for, and perhaps a little less than they should have. Their rags or other works were, for the most part, properly engraved and came with a nominally attractive original cover, a Dugdale imprint, and 200 copies with a vague promise of distribution of the rest. These were the most legitimate of the transactions.

Most of these women got what they paid for, and perhaps a little less than they should have. Their rags or other works were, for the most part, properly engraved and came with a nominally attractive original cover, a Dugdale imprint, and 200 copies with a vague promise of distribution of the rest. These were the most legitimate of the transactions.

Most of these women got what they paid for, and perhaps a little less than they should have. Their rags or other works were, for the most part, properly engraved and came with a nominally attractive original cover, a Dugdale imprint, and 200 copies with a vague promise of distribution of the rest. These were the most legitimate of the transactions.However, for whatever unknown reason, the staff of the Dugdale Company used some blind pseudonyms, no matter who was composing, for the copyright of any music put to poetry. Among the more prevalent of these names, which have not been found to be real people, were Don Loring, Vivian Brooks, Jack Stanley, Franz Hoffman, Genevieve Scott, Charles J.W. Jerreld and Ned Harvey. For Scott alone, some 150 copyright were issued in less than 16 months, and Brooks had more than 120, something that even a dedicated songwriter would be virtually incapable of with any level of consistency. Dugdale also supposedly had a promotion department that shopped the music around to prospective entertainers and music stores. The scope of this part of the operation remains somewhat obscure.

The Dugdale firm was across the street from a post office, which made them allegedly quicker to respond to correspondence and to ship the "finished" product. They were also less than fifteen minutes from the copyright office in Washington at the Library of Congress. This latter point is made clear by the sheer volume of copyrights under the five primary names in 1913 and 1914 alone, with a variety of dates, which appear to have been issued on a nearly weekly basis. They charged for this service as well, of course.

Given that even poets with little musical ability had at least some inkling of how they thought their song should sound, there were obviously some parties who were disappointed when their piece was returned and they found somebody in town who could play it for them. Others felt that Dugdale was not in the least bit interested in distributing their works, and many also wondered why the royalty checks weren't coming as promised. This resulted in letters to Dugdale and his staff, as well as copies sent to the United States Postal Service.

and many also wondered why the royalty checks weren't coming as promised. This resulted in letters to Dugdale and his staff, as well as copies sent to the United States Postal Service.

and many also wondered why the royalty checks weren't coming as promised. This resulted in letters to Dugdale and his staff, as well as copies sent to the United States Postal Service.

and many also wondered why the royalty checks weren't coming as promised. This resulted in letters to Dugdale and his staff, as well as copies sent to the United States Postal Service.On September 26, 1913, as part of a sting operation regarding several such outfits around the United States, the Dugdale offices were raided by three postal inspectors and three police sergeants. Horace, George, and their administrative assistant Marie DeVoll were taken into custody and held on a $2,000 joint bond for hearings in October. They were charged with using the mail to defraud individuals, a violation of section 215 in the criminal code, citing letters to three separate individuals as evidence. In court, Dugdale testified that he had either refunded money in the case of objections, or obtained a note of satisfaction from them.

We have always been absolutely square with our clients... We make a contract to publish music, and to give one-half of the sales to the customer, if there are any sales. Any mail order business is bound to have a few disgruntled customers.

For his part, Dugdale, perhaps trying to fend off the inevitable based on official inquiries, spent much of the next year redoubling his efforts to appear legitimate. He wrote back to many concerned individuals trying to both address their concerns and defend his company's practices. After salutations and a show of concern for the conflict, Dugdale would insist on striking up a friendship, and noting that he was open to questions asked some of his own:

A matter which I consider of great importance to you and to hundreds of other song writers in this country as well as to myself has arisen which makes it absolutely necessary for me to know at once what you and others think of the publishing service we have rendered you, and the mutual business relations we have enjoyed.

I have therefore prepared the following questions which I ask you as a friend and a business associate to answer truthfully.

1. Did our literature and letters mailed to you make it plain that you were entering into a speculation in publishing your work, and that we did not guarantee to make it a success?

2. Did you understand when you signed our contract that it covered in full everything we agreed to do for you in return for your money; and do you after reading it over feel that we have fulfilled the contract?

3. Was our musical work satisfactory?

4. Were your 200 printed copies satisfactory?

5. Were you satisfied with the manner in which we secured the copyright in your name?

6. Are you satisfied that we advertised your work as we agreed to do?

7. Are you satisfied that we rendered royalty statements to you as agreed in the contract, (provided, of course, that there were sales to report)?

8. Are you satisfied that what we have given you in return for your money was actually worth what you paid us? (Remember we arranged music, designed title, engraved plates, read proofs, printed copies, sent you 200 copies, secured copyright in your name, advertised in thematic form and in our Bulletin or Catalog, carried copies of your work in stock, and have given you any advice and assistance we could throughout the transaction with us.)

In the end, Horace and George essentially got a slap on the wrist, and were forced to close their doors and liquidate their stock. The more serious indictment of fraud was on the printer, Allyn Hayworth, who may have been considered as more accountable for the sorry state of things, being nearly two decades older than Horace. He was also forced to close his doors.

who may have been considered as more accountable for the sorry state of things, being nearly two decades older than Horace. He was also forced to close his doors.

who may have been considered as more accountable for the sorry state of things, being nearly two decades older than Horace. He was also forced to close his doors.

who may have been considered as more accountable for the sorry state of things, being nearly two decades older than Horace. He was also forced to close his doors.The aftermath left many composers around the country several dollars poorer and with a nominal or inferior product gathering dust in their storage area or music room. Some may have simply handed out copies of the music to get rid of it. A select few, usually those who had sent in a refined and nearly finished product, had more success, and their works are still found today since they likely exceeded the standard 200 copy order. But these are rare. The Dugdale situation encouraged some to aspire to seek out better publishers, noting that they were already in print, and others to turn their back on music composition as a career.

As for Dugdale, his 1917 draft record showed him now working as the advertising manager for Talbert and Parker in Washington. In late 1918, Horace, his wife, and their two children, Horace Kirkus, Jr. (1/19/1912) and William M. (5/1915), moved back to Baltimore where he worked for, then later ran an advertising agency, which seems rather fitting. The 1920 enumeration, taken in Baltimore, listed him as an advertising specialist. By the time the 1930 census was taken, he was the vice president of a firm. The 1940 enumeration listed him as an advertiser, and on his 1942 draft record Horace noted that he was a partner in the advertising firm of Van Sant, Dugdale and Company, operating at Lexington and Calvert in Baltimore according to city directories of that decade. Overall, it seems that Dugdale likely wanted to forget the whole music affair, as he appears to have not engaged in any more publishing, although he did renew some earlier copyrights in the 1930s and wrote at least one song published by Boosey in 1932.

The 1950 enumeration showed the Dugdales in Pomona, Maryland, across the Chesapeake Bay from Baltimore, trying his hand at farming, after having evidently retired from advertising. Horace and Margaret subsequently moved to Seaford, Delaware, near their oldest son's home. Margaret passed on in Seaford in 1978. Horace Dugdale died exactly two years later to the month in December, 1980, at age 90.

The author's analysis based on accumulative records is that Horace Kirkus Dugdale was initially sincere and well-intentioned in his effort to help independent poets and composers, but that he was also misguided in some ways, perhaps by Hayworth who saw an opportunity for quick profit. In the end, Dugdale did provide hope for many prospective artists, a few of which were able to achieve even more once their work was in print.

Thanks to the Library of Congress for providing some of the printed material acquired from the Dugdale firm. The rest was researched by the author in public records, music copyright records, and newspaper notices of Dugdale.

Selected Published Composers

Selected Published Composers