John Stillwell Stark (April 11, 1841 to October 21, 1927) | ||

Published Composers Published Composers | ||

|

Louise Allen

Willie Anderson Minnie Berger Arthur F. Beyer Kenneth W. Bradshaw Clarence E. Brandon Fred Brownold Carrie Brugerman (Mrs. William Stark) (as Cal Stark) Ernie Burnett Jerry Cammack Millie Carew E. L. Catlin J. W. Cole Louis Chauvin Rubey Cowan Marietta Cranston Ella Uhrig Cummins Clyde D. Douglass E. Edwards Harry E. Ellman Ebon Gay Lucian Porter Gibson Jesse G. M. Glick |

Maxwell Gordon

Walter G. Haenschen Homer A. Hall Edward A. Hallway Robert Hampton Scott Hayden Will Held Edward Hudson Charles Humfeld Charles H. Hunter Robert George Ingraham Elijah W. Jamerson Scott Joplin F. B. Kirwin Maurice Kirwin Joseph Francis Lamb Charles H. Lewis Arthur Marshall Bertha Mathews Artie Matthews Joe McGrade Edward J. Mellinger Fred L. Moreland Fay Parker |

Paul Charles Pratt

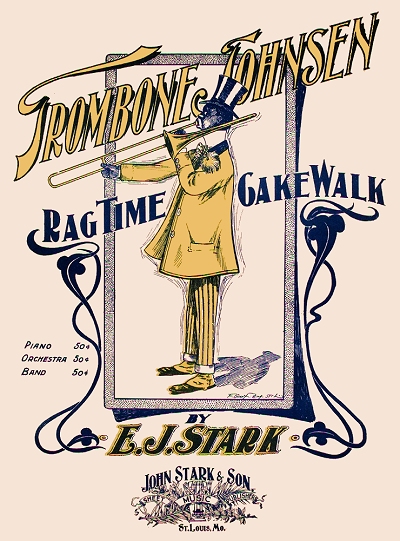

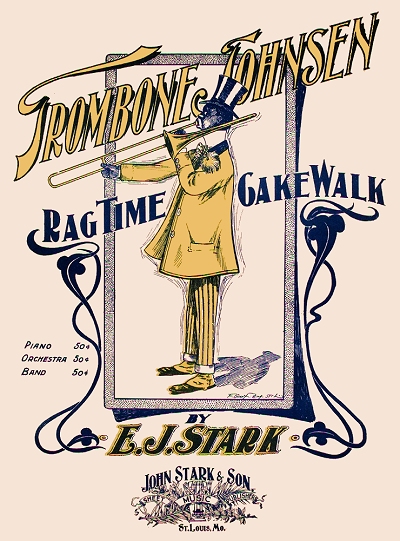

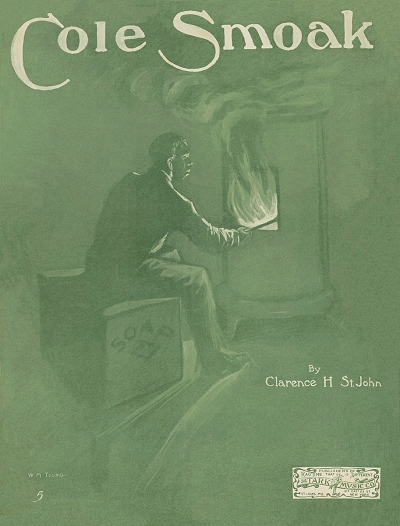

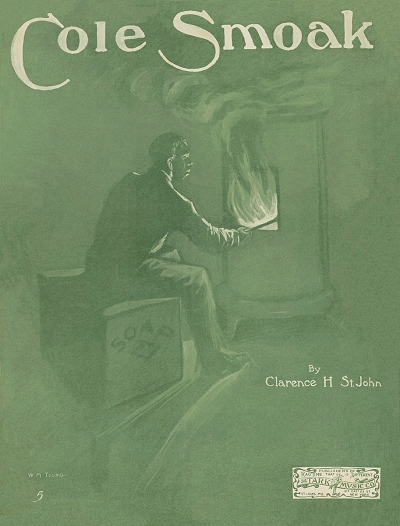

S. G. Rhodes J. Russel Robinson Charles E. Royal Clarence H. St. John James Sylvester Scott S. Lew Schwab Charles E. Shafer Arthur L. Sizemore Billy Smythe Nat E. Solomons Etilmon J. Stark (as E.J. Stark & Bud Manchester) John S. Stark Jack Steele Robert B. Stirling Clarence W. B. Sykes F. W. Westhoff B. R. Whitlow Herbert W. Willett Irving M. Wilson Sam Wishnuff Frank Wooster Milner M. York |

More than any other Midwest publisher in the ragtime era, John Stark was responsible for not only the labeling of the genre of Classic Ragtime but for recognizing and promoting the musicality of virtually every piece that was published by his firm. Yet he was also one of the oldest ragtime publishers in the beginning, and certainly the oldest who grounded the fame of his publishing house on the still-new ragtime genre.

Born in Kentucky to Adin Stark (John's death certificate offers the alternate of Aaron) and Eleanor Stillwell, John was the 11th of 12 children, the last of them dying at birth along with his mother when he was not yet three. His siblings are listed in the Stark family Bible as Norborn Perry (2/5/1819), Etilmon Justus (5/5/1820), Mary Ann (5/5/1822), Dorothy Colin (5/14/1824), Arbelia Tyrene (7/4/1826), Effie Arcada (4/11/1828), Canadasa Ellen (4/25/1830), Atlantas America Livada (11/21/1833), Nancy Sardinia (7/10/1835), Thomas P. Dudley (8/15/1838), and Lucinda C.J. (1/2/1844) who died at birth. John ended up living with Effie for three years. The family's primary existence was that of survival, as they made their own clothes and lived largely off whatever they could grow or hunt for food. By the time of the 1850 census he was living on a farm in Bean Blossom, Indiana, (reported to be Gosport, Indiana in many sources) with Etilmon. He was still there as of the 1860 census, listed as a laborer on the farm.

After having endured a hardscrabble childhood, John enlisted in the Union Army artillery in Indiana at the height of the Civil War in late 1863, serving as a bugler, and saw service in New Orleans. It was there he met British born Sarah Ann Casey, just 13½ to his 23, and they were married in a parish church in 1865 after the war ended. She went up to Etilmon's farm to wait for John, who was finally discharged in January 1866. His first post-war career was as a farmer back with his brother in Indiana, then in Missouri where he moved the new family in 1868. The 1870 census lists John and Sarah as farmers on their homestead in Camden, Missouri along with children Etilmon Justus (March 1867) and William Paris (May 30, 1869).

It was there he met British born Sarah Ann Casey, just 13½ to his 23, and they were married in a parish church in 1865 after the war ended. She went up to Etilmon's farm to wait for John, who was finally discharged in January 1866. His first post-war career was as a farmer back with his brother in Indiana, then in Missouri where he moved the new family in 1868. The 1870 census lists John and Sarah as farmers on their homestead in Camden, Missouri along with children Etilmon Justus (March 1867) and William Paris (May 30, 1869).

It was there he met British born Sarah Ann Casey, just 13½ to his 23, and they were married in a parish church in 1865 after the war ended. She went up to Etilmon's farm to wait for John, who was finally discharged in January 1866. His first post-war career was as a farmer back with his brother in Indiana, then in Missouri where he moved the new family in 1868. The 1870 census lists John and Sarah as farmers on their homestead in Camden, Missouri along with children Etilmon Justus (March 1867) and William Paris (May 30, 1869).

It was there he met British born Sarah Ann Casey, just 13½ to his 23, and they were married in a parish church in 1865 after the war ended. She went up to Etilmon's farm to wait for John, who was finally discharged in January 1866. His first post-war career was as a farmer back with his brother in Indiana, then in Missouri where he moved the new family in 1868. The 1870 census lists John and Sarah as farmers on their homestead in Camden, Missouri along with children Etilmon Justus (March 1867) and William Paris (May 30, 1869).His next career change came as he found farming not suited to his gifts, and he took up ice cream, still a fairly specialized business given the seasonal availability of ice and absence of mechanical refrigeration in the 1870s. The formula for his ice cream must have been tasty, as he actually did very well, wandering through northwest Missouri in a Conestoga wagon and selling ice cream to any farmer or small town resident he could find. After basing himself in Cameron for a time he moved the family, now including daughter Eleanor S. (May 1871), (one other child did not make it through infancy) to Chillicothe, Missouri in the late 1870s. It was there that Stark became a salesman for the Jesse French Piano Company, offering ice cream along with the musical instruments that he readily convinced rural farmers to purchase for home entertainment and culture. In the 1880 census the Stark family is shown in Chillicothe, with John selling pianos and organs. He also took up tuning to provide an added incentive for follow-up business. However, carting pianos around got tiresome and Stark, now in his mid-40s, decided he wanted the customers to come to him. Finding an opportunity in Sedalia, MO, he bought the floundering J.W. Truxel music store in 1886, and set up shop at 516 South Ohio Street in what was to become the "cradle of ragtime."

Given their close proximity to music now that the family owned a store, Eleanor took up the violin, eventually becoming a traveling concert artist after training in Europe in the mid-1890s, and Etilmon became a music teacher, as well as an arranger once his father established the publishing house. It was his less musically inclined son William who became most helpful as a business partner for the music company, which became known as John Stark & Son. When he had acquired the store he had also acquired seven copyrights in publication, and decided to continue them as well as adding a few more from local writers of the music he preferred, classically styled instrumentals. Not owning his own press, the pieces were typically printed by a jobber in St. Louis. By 1899 it appears likely that Stark was not printing anything. That was the year that life took an abrupt turn in direction for John Stark as he met head on with his future.

Not owning his own press, the pieces were typically printed by a jobber in St. Louis. By 1899 it appears likely that Stark was not printing anything. That was the year that life took an abrupt turn in direction for John Stark as he met head on with his future.

Not owning his own press, the pieces were typically printed by a jobber in St. Louis. By 1899 it appears likely that Stark was not printing anything. That was the year that life took an abrupt turn in direction for John Stark as he met head on with his future.

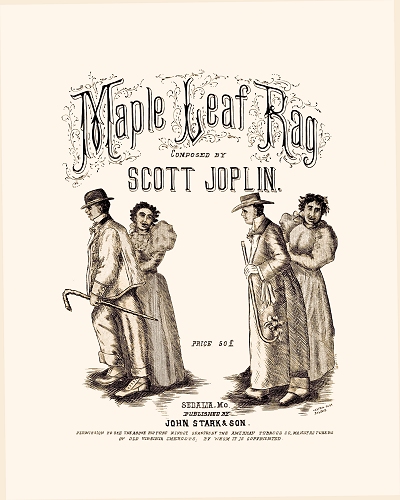

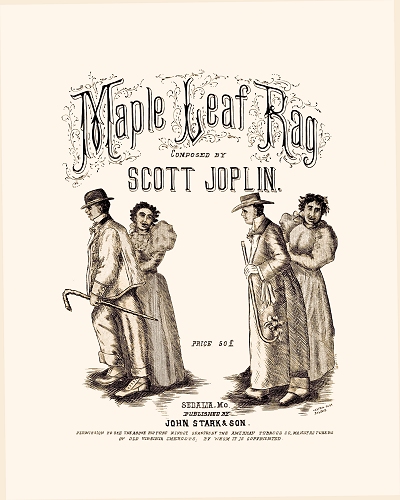

Not owning his own press, the pieces were typically printed by a jobber in St. Louis. By 1899 it appears likely that Stark was not printing anything. That was the year that life took an abrupt turn in direction for John Stark as he met head on with his future.There are varying stories on how Stark and Scott Joplin met. However, this represents a likely amalgamation in which the truth exists somewhere. Joplin had been living in Sedalia for around three years, during which he attended school for further music and general education, and published only one piece in early 1899, Original Rags, through the Carl Hoffman firm in Kansas City. Joplin believed in his new signature piece, named after a short-lived Sedalia club for black performers and associates, that he sought out a lawyer who had previously had contact with Joplin to formulate some paperwork. According to historian Ed Berlin in King of Ragtime, it is highly possible that Joplin already had the paperwork in hand when he went to visit Stark to demonstrate the piece, accompanied by, according to some stories, a little boy whose job it was to demonstrate how danceable the piece was. However that August, 1899 afternoon transpired in Stark's office, Stark was intrigued enough to look over the paperwork, accept a few alterations, and agree not only to publish Maple Leaf Rag (a bold move for a classical-loving musician) but to accept the contention of Joplin or his lawyer that a royalty be paid on sales of the piece. Four hundred were printed in St. Louis, and they sold relatively quickly - actually in about a year from the September debut.

Stark's decision in 1900 to move to St. Louis and expand was predicated largely on the basis that the Westover Printing Company in St. Louis was too busy to do a quick reprint of the piece when it was requested. So he set up shop with his own press - actually the Westover presses since he simply bought the company instead of arguing with them - and Stark & Son became a new St. Louis institution. In the 1900 census, John curiously still shows up as a piano tuner and William as a piano delivery truck driver. Joplin soon followed Stark, as did Scott Hayden, one of Joplin's pupils and the brother of his (possibly) bride Belle. Ragtime had been published in St. Louis since 1897 when Tom Turpin's Harlem Rag made the rounds, but the quality of compositions that Stark sought and accepted would be head and shoulders above most of what was published in the Midwest during the era. Whether he inspired those who wrote for him to a higher level, or was just very discerning in what he picked for publication matters less than how earnestly a 60 year-old man became involved in forwarding the cause of a young person's music of a different race than his, and how well he championed it in both actions and in print.

Whether he inspired those who wrote for him to a higher level, or was just very discerning in what he picked for publication matters less than how earnestly a 60 year-old man became involved in forwarding the cause of a young person's music of a different race than his, and how well he championed it in both actions and in print.

Whether he inspired those who wrote for him to a higher level, or was just very discerning in what he picked for publication matters less than how earnestly a 60 year-old man became involved in forwarding the cause of a young person's music of a different race than his, and how well he championed it in both actions and in print.

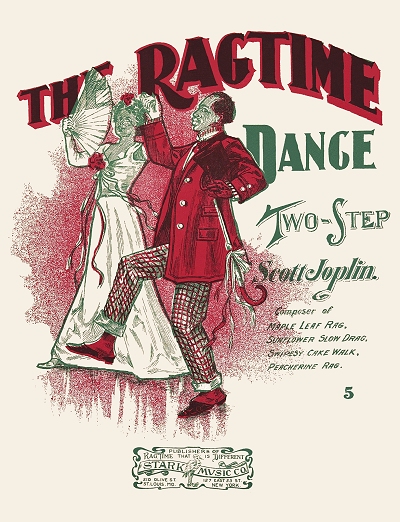

Whether he inspired those who wrote for him to a higher level, or was just very discerning in what he picked for publication matters less than how earnestly a 60 year-old man became involved in forwarding the cause of a young person's music of a different race than his, and how well he championed it in both actions and in print.The relationship between Stark and his star composer became contentious at times, with Joplin going to other firms to have one or another thing published, and Stark slowly taking on more ragtime composers. While Stark believed in the music that the composers were turning in to him, he had also developed enough business acumen to find the balance between art and viability, since two of Joplin's projects were turned down when first presented to him because of their scope. The Ragtime Dance was a ballet of sorts, a series of known dances intended for stage performance, and one that Stark deemed likely to fail in terms of sales. The second was Joplin's first opera, A Guest of Honor, likely based on the legendary 1901 visit of Booker T. Washington to the White House to meet and dine with President Theodore Roosevelt. Stark eventually conceded to the former, and his predictions of slow sales were correct. Joplin went on with the opera on his own, which is in part why no copies of it exist today. But it was simply good business that still regarded the art in the end.

While in St. Louis, the Stark store moved to four different locations, taking on more selected compositions during his tenure there. Oddly, while some St. Louis publishers tended to almost specialize in pieces that capitalized on the St. Louis Exposition of 1904, the best that Stark had to offer was Joplin's own The Cascades, albeit one of the only rags actually performed on the fairgrounds in the beautiful music hall that topped the very cascades pictured on the cover. Stark also had to press for other material since Joplin went through a slump following a series of personal tragedies in his life. By mid-1905, with the fair now gone, many of the pianists and composers were migrating to more profitable climates, Chicago and New York among the most prevalent of these. Stark hung on as best he could, offering more than just ragtime in his catalog, and even publishing his own monthly called The Intermezzo which centered around that catalog. However, he saw where the center of ragtime publishing was shifting, and in August of 1905 moved his renamed firm, Stark Music Company, to New York City.

John Stark was not well suited for the cutthroat competition and business practices of Manhattan's Tin Pan Alley. He did not associate professionally or socially with other publishers, and surprisingly with none of the many recording companies that were always looking for new popular material. But he also did not compete either, with little commercial advertising and only limited distribution despite being in the publishing center of the world. He ran his business more like an accountant than a promoter, and looked the part as well. In that vein, he made it clear that if anybody bought one of his publications for any discount off the asking price that they should report this practice to him at once! But it was in New York City that Stark started solidifying the genre of Classic Ragtime through his publications.

But he also did not compete either, with little commercial advertising and only limited distribution despite being in the publishing center of the world. He ran his business more like an accountant than a promoter, and looked the part as well. In that vein, he made it clear that if anybody bought one of his publications for any discount off the asking price that they should report this practice to him at once! But it was in New York City that Stark started solidifying the genre of Classic Ragtime through his publications.

But he also did not compete either, with little commercial advertising and only limited distribution despite being in the publishing center of the world. He ran his business more like an accountant than a promoter, and looked the part as well. In that vein, he made it clear that if anybody bought one of his publications for any discount off the asking price that they should report this practice to him at once! But it was in New York City that Stark started solidifying the genre of Classic Ragtime through his publications.

But he also did not compete either, with little commercial advertising and only limited distribution despite being in the publishing center of the world. He ran his business more like an accountant than a promoter, and looked the part as well. In that vein, he made it clear that if anybody bought one of his publications for any discount off the asking price that they should report this practice to him at once! But it was in New York City that Stark started solidifying the genre of Classic Ragtime through his publications.His star composer followed Stark to New York in 1907. Joplin was recovering from the loss of his second wife, and some of his self-perceived failures as a composer to date. The move strengthened him personally and he started submitting pieces to publishers once again, including Stark, who was also now putting out virtually anything sent to him by the Missouri composer James Scott through the still functioning St. Louis office. There was one New Jersey composer who had also tried submitting to Stark with limited success in 1906. During a late 1907 visit to Stark's office to purchase music, Joseph F. Lamb commented to Mrs. Stark how much he would like to meet Joplin. As luck would have it, Joplin was also in the office, leg wrapped up from the gout, and after a short meeting Joplin agreed to listen to Lamb's works. Once Lamb demonstrated them at Joplin's home, the elder composer offered to intercede for him with Stark, a fortuitous choice that eventually solidified for all time Stark's firm as the top echelon of classic ragtime publishers. After the publication and success of Lamb's Sensation, Stark published anything the composer sent him.

A positive attribute that set Stark apart from other publishers had been, at least for a while, the financial arrangements with most of them. While some were satisfied with a simple sale of a piece, Stark's favored method became to pay a pittance for the piece initially, but as with Maple Leaf Rag, offer a penny royalty per copy, a better long-term gain for all involved. This changed in 1908 as Stark hardened his stance and started offering payment per each printing, not always following through. This soon alienated Joplin, who had become used to the regular checks, and incensed others as well who started heading towards other publishing houses. Lamb still remained on good terms with Stark, and even wrote Contentment Rag for John and Sarah as he thought they were such a loving couple. Often complaining about the practices of music retailers in New York City, Stark further alienated himself from the publishing and composing community, and in early 1910 finally retreated back to St. Louis with his ailing wife. They were in St. Louis by the time of the April 1910 census, boarding with Frank Call at 4147 Laclede Avenue. Sarah died on November 14, 1910. Contentment Rag would be issued later, but without any acknowledgment of Lamb's heartfelt dedication.

Often complaining about the practices of music retailers in New York City, Stark further alienated himself from the publishing and composing community, and in early 1910 finally retreated back to St. Louis with his ailing wife. They were in St. Louis by the time of the April 1910 census, boarding with Frank Call at 4147 Laclede Avenue. Sarah died on November 14, 1910. Contentment Rag would be issued later, but without any acknowledgment of Lamb's heartfelt dedication.

Often complaining about the practices of music retailers in New York City, Stark further alienated himself from the publishing and composing community, and in early 1910 finally retreated back to St. Louis with his ailing wife. They were in St. Louis by the time of the April 1910 census, boarding with Frank Call at 4147 Laclede Avenue. Sarah died on November 14, 1910. Contentment Rag would be issued later, but without any acknowledgment of Lamb's heartfelt dedication.

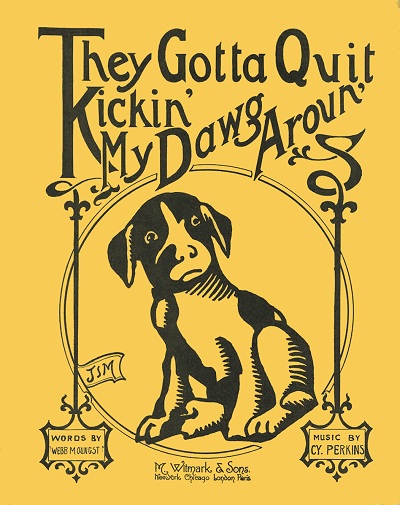

Often complaining about the practices of music retailers in New York City, Stark further alienated himself from the publishing and composing community, and in early 1910 finally retreated back to St. Louis with his ailing wife. They were in St. Louis by the time of the April 1910 census, boarding with Frank Call at 4147 Laclede Avenue. Sarah died on November 14, 1910. Contentment Rag would be issued later, but without any acknowledgment of Lamb's heartfelt dedication.Over the next couple of years the Stark firm would add both J. Russel Robinson and Artie Matthews to his ragtime cartel, and both would turn out hits for them. Among the first of these was a Matthews arrangement of the 1912 piece They Gotta Quit Kickin' My Dawg Aroun' composed (still disputed by some) in part by William Stark's wife, Carrie (Bruggerman) Stark for Missouri congressman and Democratic Presidential candidate Champ Clark. It rapidly gained momentum, and soon publisher M. Witmark offered $10,000 for the piece, which Stark, a bit stunned, accepted. The piece instantly lost favor when Clark lost his bid to Woodrow Wilson, but it helped Stark indulge in his growing passion for classic ragtime. Matthews also contributed a number of other significant arrangements for Stark and also Tom Turpin, most of the latter never having been published. Robinson, though often traveling, made some nice contributions to the catalog, including his That Eccentric Rag. James Scott and Joseph Lamb were also helping to feed his classic rag factory. One of his more significant contributions in 1912, an orchestra/band folio titled Standard High Class Rags which would more commonly known as the "Red Back Book" because of the rear cover. By offering fully formed orchestrations of rags in his catalog, he further promoted his works through the concerts given by those who played the 15 fine arrangements, including some of and by his most famous contributor, Scott Joplin.

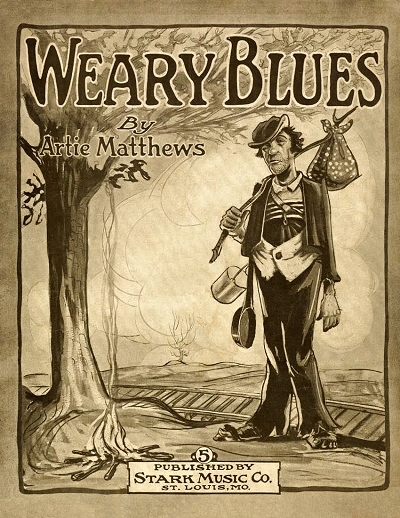

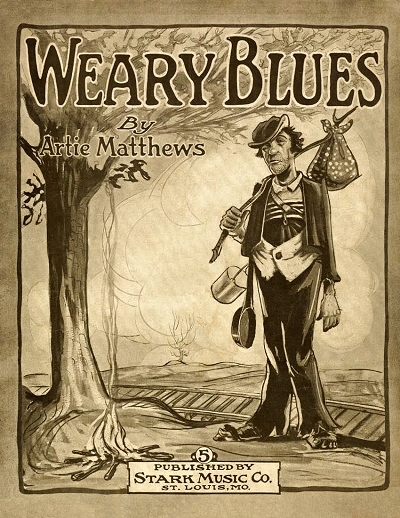

Also in 1912, in an effort to get rags into print, yet not directly acknowledge those he felt quite up to his high standards, Stark started the Syndicate Music Publishing Company. In the end, only eight rags were ever printed under this label, including the underrated Lily Rag by Charles Thompson, deftly arranged by Matthews. It was Artie who would raise the standard for Missouri ragtime with his five Pastime Rags, for which Stark offered $50 each in 1913. Some were so advanced that Stark would end up issuing the last three long after Matthews had left St. Louis. Matthews also made another pile of money for Stark based on a plea from the publisher for one of his composers to submit a blues that could compete with those by Handy. Artie quickly turned out Weary Blues, an enduring hit, for which he not only received payment, but some additional money for a new suit, uncharacteristic of the increasingly frugal publisher. Another fine composer, Paul Pratt from Indianapolis, Indiana, started contributing to Stark in 1914 after his previous publisher, John Aufderheide, closed up shop. His Springtime Rag represented a significant bump in the quality of Stark sheets in print, and Hot House Rag has been performed consistently since Stark first issued it.

Some were so advanced that Stark would end up issuing the last three long after Matthews had left St. Louis. Matthews also made another pile of money for Stark based on a plea from the publisher for one of his composers to submit a blues that could compete with those by Handy. Artie quickly turned out Weary Blues, an enduring hit, for which he not only received payment, but some additional money for a new suit, uncharacteristic of the increasingly frugal publisher. Another fine composer, Paul Pratt from Indianapolis, Indiana, started contributing to Stark in 1914 after his previous publisher, John Aufderheide, closed up shop. His Springtime Rag represented a significant bump in the quality of Stark sheets in print, and Hot House Rag has been performed consistently since Stark first issued it.

Some were so advanced that Stark would end up issuing the last three long after Matthews had left St. Louis. Matthews also made another pile of money for Stark based on a plea from the publisher for one of his composers to submit a blues that could compete with those by Handy. Artie quickly turned out Weary Blues, an enduring hit, for which he not only received payment, but some additional money for a new suit, uncharacteristic of the increasingly frugal publisher. Another fine composer, Paul Pratt from Indianapolis, Indiana, started contributing to Stark in 1914 after his previous publisher, John Aufderheide, closed up shop. His Springtime Rag represented a significant bump in the quality of Stark sheets in print, and Hot House Rag has been performed consistently since Stark first issued it.

Some were so advanced that Stark would end up issuing the last three long after Matthews had left St. Louis. Matthews also made another pile of money for Stark based on a plea from the publisher for one of his composers to submit a blues that could compete with those by Handy. Artie quickly turned out Weary Blues, an enduring hit, for which he not only received payment, but some additional money for a new suit, uncharacteristic of the increasingly frugal publisher. Another fine composer, Paul Pratt from Indianapolis, Indiana, started contributing to Stark in 1914 after his previous publisher, John Aufderheide, closed up shop. His Springtime Rag represented a significant bump in the quality of Stark sheets in print, and Hot House Rag has been performed consistently since Stark first issued it.The backs and inside of Stark covers made clear his view on the quality of what he was publishing as well as how it should be played, and the same was true in his newspaper ads and brochures. For example, when touting a Joplin piece he insisted, "Play every note of this number just as it is written and don't add any notes or flourishes. There is a meaning in every hue, and faking kills it." There was endless hyperbole on any new number by James Scott, and he even took Joplin to task at times, lauding the drop in quality of some of his works compared to Maple Leaf Rag and other Stark issues. The material put out by others, in his view, was also sub-standard, silly, slush, or just plain inferior in his view. However, his reign was coming to an end in the mid-1910s. Between 1906, after the World's Fair traffic and many venues had dried up, and 1914, many of the St. Louis musicians migrated to Chicago or New York where there was more employment. When Matthews left for Chicago, then Cincinnati, he lost his best staff composer and arranger. Then came two nearly simultaneous crushing blows.

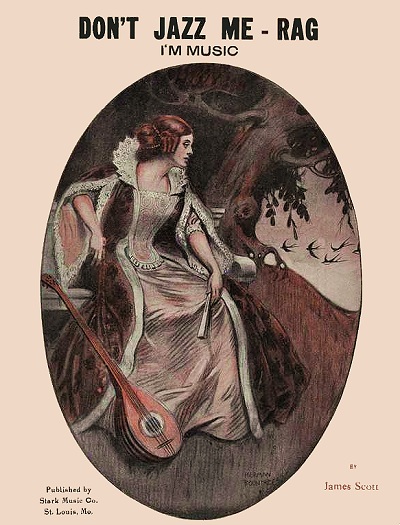

Scott Joplin died on April 1, 1917, and the Original Dixieland Jazz Band started issuing recordings about that same time. The two events became a symbolic indication that ragtime was nearly out of vogue, and jazz was taking over. Stark bristled at this very clearly in his writings, but after 1917 his publications quickly dwindled. He was pulling manuscripts out of the archives from years before, including Matthews' remaining rags, and even claimed to have a couple more Joplin manuscripts at the time he published Reflection Rag shortly after the composer's death. Even Joe Lamb had stopped contributing, and in the end, James Scott was one of the last to send anything down to St. Louis from his now Kansas City home. In order to both cut costs and honor the U.S. Government's call for paper conservation during World War One, the sheets were reduced in size and the printing made smaller as well. Some of the 1918 to 1921 rags represent material that used to be on four or more 10" x 13" pages, and now were crowded, sometimes without the traditional reiteration of the A section, on two 9" x 12" pages. Blues, jazz and novelty piano pieces did not require so much density, and further helped to crowd out ragtime publications. In frustration, he named one of his final publications of James Scott in 1921 Don't Jazz Me - Rag (I'm Music). But it was already too late, and even Scott had started to play some jazz styles with his Kansas City band. An effort to promote his older rags as possible B-sides on Edison Diamond Discs also fell flat. In 1920 at age 79, Stark was shown living in the Maplewood area of St. Louis with Etilmon and his family, still listed as a music publisher.

In order to both cut costs and honor the U.S. Government's call for paper conservation during World War One, the sheets were reduced in size and the printing made smaller as well. Some of the 1918 to 1921 rags represent material that used to be on four or more 10" x 13" pages, and now were crowded, sometimes without the traditional reiteration of the A section, on two 9" x 12" pages. Blues, jazz and novelty piano pieces did not require so much density, and further helped to crowd out ragtime publications. In frustration, he named one of his final publications of James Scott in 1921 Don't Jazz Me - Rag (I'm Music). But it was already too late, and even Scott had started to play some jazz styles with his Kansas City band. An effort to promote his older rags as possible B-sides on Edison Diamond Discs also fell flat. In 1920 at age 79, Stark was shown living in the Maplewood area of St. Louis with Etilmon and his family, still listed as a music publisher.

In order to both cut costs and honor the U.S. Government's call for paper conservation during World War One, the sheets were reduced in size and the printing made smaller as well. Some of the 1918 to 1921 rags represent material that used to be on four or more 10" x 13" pages, and now were crowded, sometimes without the traditional reiteration of the A section, on two 9" x 12" pages. Blues, jazz and novelty piano pieces did not require so much density, and further helped to crowd out ragtime publications. In frustration, he named one of his final publications of James Scott in 1921 Don't Jazz Me - Rag (I'm Music). But it was already too late, and even Scott had started to play some jazz styles with his Kansas City band. An effort to promote his older rags as possible B-sides on Edison Diamond Discs also fell flat. In 1920 at age 79, Stark was shown living in the Maplewood area of St. Louis with Etilmon and his family, still listed as a music publisher.

In order to both cut costs and honor the U.S. Government's call for paper conservation during World War One, the sheets were reduced in size and the printing made smaller as well. Some of the 1918 to 1921 rags represent material that used to be on four or more 10" x 13" pages, and now were crowded, sometimes without the traditional reiteration of the A section, on two 9" x 12" pages. Blues, jazz and novelty piano pieces did not require so much density, and further helped to crowd out ragtime publications. In frustration, he named one of his final publications of James Scott in 1921 Don't Jazz Me - Rag (I'm Music). But it was already too late, and even Scott had started to play some jazz styles with his Kansas City band. An effort to promote his older rags as possible B-sides on Edison Diamond Discs also fell flat. In 1920 at age 79, Stark was shown living in the Maplewood area of St. Louis with Etilmon and his family, still listed as a music publisher.In 1925 after three years of no new pieces, Stark sold the Standard High Class Rags folio to the Melrose Brothers in Chicago. He still went to work in his eighties, but had little to do except arrange for the occasional reprint of Maple Leaf Rag or Frog Legs Rag as scant orders came in. When Lottie (Stokes Joplin) Thomas, Scott Joplin's remarried widow, renewed the copyright for Maple Leaf Rag in 1925 she made sure that Stark maintained publication rights to the piece that started his empire. The old man finally wore out, and left the world behind in October 1927 at age 86, as a result of "chronic vascular cardiac condition," and was buried next to his beloved Sarah. While the date has long been shown to be November 20, 1927 in published and web sources, this is incorrect. It goes back to the publication of They All Played Ragtime in 1950, when the authors may have received faulty information from a family member. His death certificate clearly shows a date of death of October 21, and burial in St. Peter's Cemetery of St. Louis on October 23, 1927.

The family maintained the vestiges of the publishing house for a few years, but eventually sold off the properties and turned it back into a commercial printing house. Interviews by historian Rudi Blesh with the Stark family for They All Played Ragtime did not reveal what may have happened to the many unpublished works in the Stark archives, but there are indications that they were simply destroyed as the business changed purposes, since there seemed to be little interest in ragtime at that point in the 1940s. Today, Stark is remembered as a very important figure in the best of ragtime, having promoted the finest works by any race or gender, and even giving the genre of "classic ragtime" its name. Stark Music Company - Publishers of Music That is Different.

Some of the information in this biography, both correct and incorrect, can be found in several sources, including the book That American Rag by Dave Jasen and Gene Jones, which should be a staple in any ragtime library. Other facets were found or confirmed by the author, including a review of notes by Rudi Blesh when he was researching for They All Played Rag in 1949, and various public records and newspaper articles.