Robert Walter Jacobs was one of three siblings born to German dry goods merchant Arland Jacobs and his Ohio-born wife Harriet in Oberlin, Ohio, the others being Emma (1865) and Harry A. (1871). Arland died in the late 1870s, and the 1880 census showed the widowed Emma and her family still living in Oberlin, but with no occupation listed for any of them.

According to a short profile published in Contributions to the Art of Music in America by the Music Industries of Boston, 1640-1936, when Jacobs was ten he heard a group of Negro street guitarists, and was intrigued enough by their playing that he obtained a guitar and taught himself how to perform on it. With diligence Walter became a highly skilled player, and was able to formulate his own teaching method. He left Oberlin around 1890, and by 1891 he was listed as both living and working in Boston as a plucked string player and teacher. His focus was on banjo and guitar, as noted in city directories from 1892 and later. He also placed advertisements in the Boston Globe that read: "Banjo, Guitar and Mandolin, $5 course, R. Walter Jacobs, 297 Tremont st., Suite 1." Ads from 1893 showed him to be a member of the Euterpe Club, a branch of a national music organization, and as a merchant in banjos, guitars, and now mandolins.

He also placed advertisements in the Boston Globe that read: "Banjo, Guitar and Mandolin, $5 course, R. Walter Jacobs, 297 Tremont st., Suite 1." Ads from 1893 showed him to be a member of the Euterpe Club, a branch of a national music organization, and as a merchant in banjos, guitars, and now mandolins.

He also placed advertisements in the Boston Globe that read: "Banjo, Guitar and Mandolin, $5 course, R. Walter Jacobs, 297 Tremont st., Suite 1." Ads from 1893 showed him to be a member of the Euterpe Club, a branch of a national music organization, and as a merchant in banjos, guitars, and now mandolins.

He also placed advertisements in the Boston Globe that read: "Banjo, Guitar and Mandolin, $5 course, R. Walter Jacobs, 297 Tremont st., Suite 1." Ads from 1893 showed him to be a member of the Euterpe Club, a branch of a national music organization, and as a merchant in banjos, guitars, and now mandolins.Around 1894 Walter, who had already self-issued a couple of his own works was persuaded by violinist Tommy Allen to purchased ten of his numbers for a total of $5. This formed the basis of the Walter Jacobs publishing company, and he soon expanded his enterprise to a suite of studios and was selling a booklet of Jacobs; Banjo Studies for beginners at 25 cents each. Starting at 167 Tremont street, then moving to 169 Tremont, Jacobs would occupy various suites and buildings on that block for the next two decades. Boston city directory references after 1893 read as Walter Jacobs, as he had dropped the first initial for Robert. Advertisements and mentions from 1895 and later refer to him as "Professor Walter Jacobs," although this was at times an adornment or self-appointed title in the late nineteenth century, rather than an academic title.

Throughout the late 1890s Walter played at concerts of various sizes, as per some notices in the Boston newspapers, and occasionally with plucked string groups, which were increasingly in vogue around this time. In the January 27, 1900, edition of the Music Trade Review, he endorsed the Bay State Guitar Company (sold by a couple of other Boston dealers), saying, "I use them constantly in my concert work, and find them all that the most exacting critic could desire." As early as 1898 he was listed in Boston city directories as a music publisher. However, In the July 14, 1900, edition of the MTR, he was shown as a contributor to a folio of Superb Banjo Solos published by the rival White-Smith Music Publishing Company, perhaps acquired prior to his entry into his own enterprise. Jacobs was not located in the 1900 Federal census, but he was clearly living and working in Boston at that time.

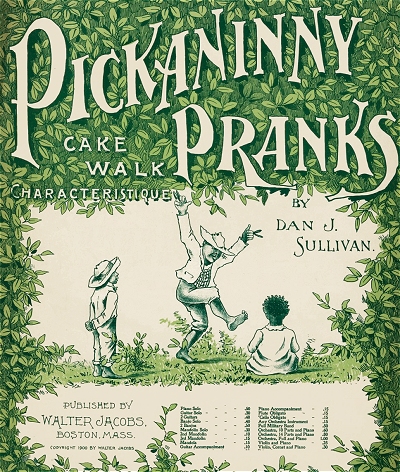

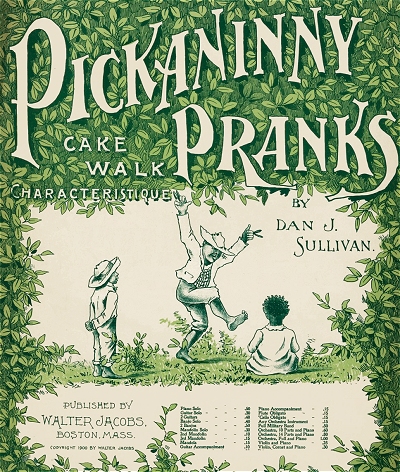

Although he was putting out syncopated piano works as early as 1898, many of Walter's early publications were string band-oriented, and therefore instrumentals. In fact, it was notable enough in 1903 when he first published a song that the MTR commented on the event. The song was Mr. Moon, Kindly Come Out and Shine by Smith & Bowman, who are well known to ragtime fans as the composers of Good Morning Carrie. He also put out a Grand Orchestra Folio for 23 different standard orchestral instruments, including arrangements of some current ragtime favorites and marches. One of the standouts which gave his company more visibility was an arrangement of Thomas S. Allen's hit Any Rags?, purchased from publisher George Krey. A more standard piano repertoire was close at hand, although Jacobs continued to arrange and publish for plucked string ensembles as well. Several pieces from 1903 to 1905 were either published for piano or intended for full mandolin orchestra with piano accompaniment, although songs were still a rarity under his imprint.

The song was Mr. Moon, Kindly Come Out and Shine by Smith & Bowman, who are well known to ragtime fans as the composers of Good Morning Carrie. He also put out a Grand Orchestra Folio for 23 different standard orchestral instruments, including arrangements of some current ragtime favorites and marches. One of the standouts which gave his company more visibility was an arrangement of Thomas S. Allen's hit Any Rags?, purchased from publisher George Krey. A more standard piano repertoire was close at hand, although Jacobs continued to arrange and publish for plucked string ensembles as well. Several pieces from 1903 to 1905 were either published for piano or intended for full mandolin orchestra with piano accompaniment, although songs were still a rarity under his imprint.

The song was Mr. Moon, Kindly Come Out and Shine by Smith & Bowman, who are well known to ragtime fans as the composers of Good Morning Carrie. He also put out a Grand Orchestra Folio for 23 different standard orchestral instruments, including arrangements of some current ragtime favorites and marches. One of the standouts which gave his company more visibility was an arrangement of Thomas S. Allen's hit Any Rags?, purchased from publisher George Krey. A more standard piano repertoire was close at hand, although Jacobs continued to arrange and publish for plucked string ensembles as well. Several pieces from 1903 to 1905 were either published for piano or intended for full mandolin orchestra with piano accompaniment, although songs were still a rarity under his imprint.

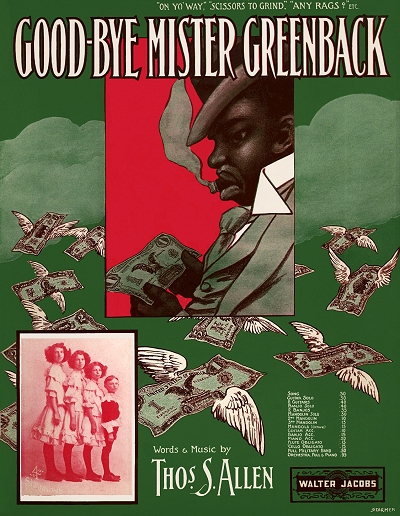

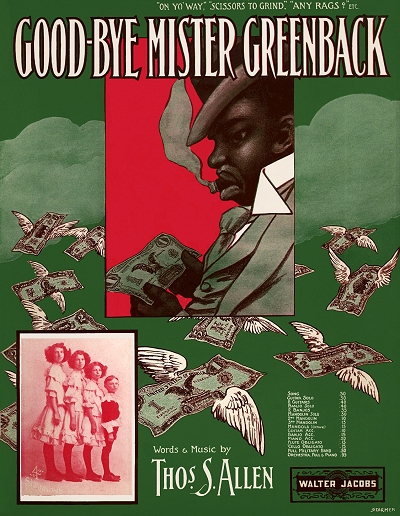

The song was Mr. Moon, Kindly Come Out and Shine by Smith & Bowman, who are well known to ragtime fans as the composers of Good Morning Carrie. He also put out a Grand Orchestra Folio for 23 different standard orchestral instruments, including arrangements of some current ragtime favorites and marches. One of the standouts which gave his company more visibility was an arrangement of Thomas S. Allen's hit Any Rags?, purchased from publisher George Krey. A more standard piano repertoire was close at hand, although Jacobs continued to arrange and publish for plucked string ensembles as well. Several pieces from 1903 to 1905 were either published for piano or intended for full mandolin orchestra with piano accompaniment, although songs were still a rarity under his imprint.Walter's enterprise grew steadily over the next few years, as he also opened a store at his Tremont Street location. Addresses in directories of the period show that he occupied 169, 167 and 165 Tremont at various times, perhaps all three by 1908. Along with his publishing he was selling music and offering lessons, likely with additional teachers, and focused on plucked strings. In 1906 he published a song that got him into some legal trouble, at least concerning his method of advertising it. The piece was Good-bye Mister Greenback by Thomas S. Allen, a "coon" song lamenting the constant flow of money out of one's hands rather than into them. His method of advertising was to circulate a relatively accurate, if clearly fake representation of a $5 bill with the title lyric inscribed on it, "Good-bye, Mr. Greenback, I hate to see you go." His clever ploy landed him in a municipal court in short order, where he was arraigned, then fined a total of three authentic $5 bills and warning to not try even counterfeit counterfeiting again. Publicity is still publicity, and the song sold and recorded quite well.

In a town where most publishers, including stalwart Oliver Ditson, continued to stick with more artful or classical works, Jacobs was quickly becoming known as one of the lead publishers of popular music in Boston. By 1907 Jacobs had pieces distributed throughout most of the United States and southern Canada, and even across the pond into England. Jacobs suffered a minor setback in December of 1907 when a warehouse fire destroyed some $4,000 of his stock. However, insurance covered the loss and he immediately was able to recover the lost stock, keeping Walter's supply flow of new music circulating with little hesitation.

Trade advertisements from 1908 showed a rather impressive catalog, which included some current ragtime hits such as Persian Lamb Rag by Percy Wenrich, plus a number of vocal ballads, popular songs, and instrumentals for both piano and string ensembles. In July of that year he followed a trend among publishers of the time, issuing his own periodical, The Cadenza. Actually, he purchased an existing paper, then revamped it in his image, featuring some of his publications, stories on composers and music, and instructional material as well, focused largely on banjo, mandolin and guitar. Jacobs edited the tome, along with well-known writer Erastus Osgood, whom he hired as his associate. Jacobs also became a bit more active in the legal affairs of publishers, making the occasional trip to Washington, DC, for discussions on changes to vague copyright laws, and other fiscal issues faced by those in his profession.

In July of that year he followed a trend among publishers of the time, issuing his own periodical, The Cadenza. Actually, he purchased an existing paper, then revamped it in his image, featuring some of his publications, stories on composers and music, and instructional material as well, focused largely on banjo, mandolin and guitar. Jacobs edited the tome, along with well-known writer Erastus Osgood, whom he hired as his associate. Jacobs also became a bit more active in the legal affairs of publishers, making the occasional trip to Washington, DC, for discussions on changes to vague copyright laws, and other fiscal issues faced by those in his profession.

In July of that year he followed a trend among publishers of the time, issuing his own periodical, The Cadenza. Actually, he purchased an existing paper, then revamped it in his image, featuring some of his publications, stories on composers and music, and instructional material as well, focused largely on banjo, mandolin and guitar. Jacobs edited the tome, along with well-known writer Erastus Osgood, whom he hired as his associate. Jacobs also became a bit more active in the legal affairs of publishers, making the occasional trip to Washington, DC, for discussions on changes to vague copyright laws, and other fiscal issues faced by those in his profession.

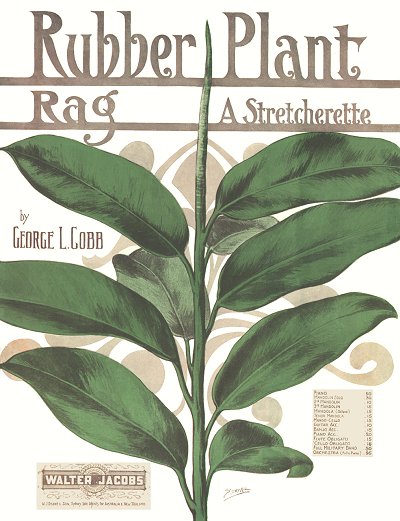

In July of that year he followed a trend among publishers of the time, issuing his own periodical, The Cadenza. Actually, he purchased an existing paper, then revamped it in his image, featuring some of his publications, stories on composers and music, and instructional material as well, focused largely on banjo, mandolin and guitar. Jacobs edited the tome, along with well-known writer Erastus Osgood, whom he hired as his associate. Jacobs also became a bit more active in the legal affairs of publishers, making the occasional trip to Washington, DC, for discussions on changes to vague copyright laws, and other fiscal issues faced by those in his profession.The year 1909 marked Walter's initial association with composer George L. Cobb, who would eventually become a star of sorts in the Jacobs universe. Emboldened by a prize he had recently won for a composition in Buffalo, New York, the talented Cobb set forth with the ambitious Rubber Plant Rag, published by Jacobs late in the year. It gave the composer national exposure, and the publisher a first rate piano rag. It would be a few more years before Cobb worked regularly for Walter, but the latter did publish a handful of his songs and instrumentals over the next several years. He also snagged the eclectic catalog of New York composer and publisher Theodore Bendix in 1909, further expanding his massive repertoire of works, including method books for clarinet and violoncello.

The 1910 census showed Walter lodging with another family, as he appeared to have done during most of his life, likely given that he had little time or inclination to maintain a home of his own. His profession was listed as music publisher for that enumeration. His Jacobs' Orchestra Monthly was making a splash that year, and had a new fully orchestrated work in it each month, including a number of piano rags for band or string ensemble, all promoting his catalog, of course. This monthly, which debuted with a run of 75,000 copies, was one of his most earnest projects in which he materially participated, and by 1913 it was expanded to over 100 pages per issue.

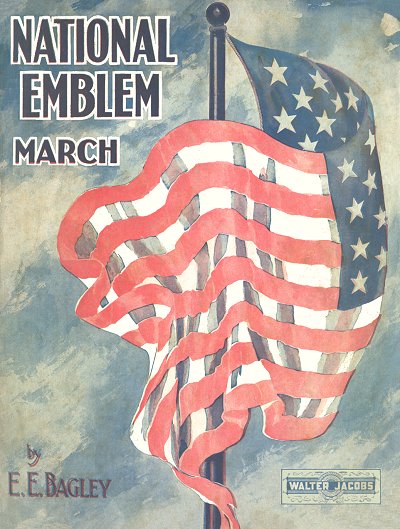

One of Walter's best acquisitions of 1911 was the Ernest S. Williams catalog of band, orchestra, vocal and instrumental music. It included the soon-to-be overplayed, frequently recorded and often lampooned National Emblem March by Edwin Eugene (E.E.) Bagley. Even stalwart march composer John Philip Sousa cited National Emblem as one of the three most effective street marches ever written. It would remain a staple in the Jacobs catalog into the 1920s. In the late 1910s, Jacobs had lyrics added to the work to renew interest in it as a march song titled That's What the Red, White and Blue Means (To Ev'ry True Heart in the U.S.A.). These were taken from the winning entry of a $100 competition that yielded over 400 entries, many of them referring to the war in Europe, giving them less longevity.

In the late 1910s, Jacobs had lyrics added to the work to renew interest in it as a march song titled That's What the Red, White and Blue Means (To Ev'ry True Heart in the U.S.A.). These were taken from the winning entry of a $100 competition that yielded over 400 entries, many of them referring to the war in Europe, giving them less longevity.

In the late 1910s, Jacobs had lyrics added to the work to renew interest in it as a march song titled That's What the Red, White and Blue Means (To Ev'ry True Heart in the U.S.A.). These were taken from the winning entry of a $100 competition that yielded over 400 entries, many of them referring to the war in Europe, giving them less longevity.

In the late 1910s, Jacobs had lyrics added to the work to renew interest in it as a march song titled That's What the Red, White and Blue Means (To Ev'ry True Heart in the U.S.A.). These were taken from the winning entry of a $100 competition that yielded over 400 entries, many of them referring to the war in Europe, giving them less longevity.In addition to his publishing enterprise, Walter served for a while in the early 1910s as the secretary and treasurer of the American Guild of Banjoists, Guitarists and Mandolinists, of which he had been a member since its inception 1902. The Cadenza was adopted as their official magazine in January of 1913. Walter was also on a number of committees in local musical organizations, and remained active in influencing Federal legislation of copyright protections. Jacobs was frequently cited as one of the hardest workers in the business in editions of the MTR, Boston newspapers, and New York music trade papers. As to his success, Walters was quoted in the MTR of September 10, 1910, as having "modestly replied," that it was due to "Unswerving honesty and square dealing, systematic attention to the smallest details, prompt payment of bills and a big slice of downright hard work."

That hard work, including his catalog of popular songs, arrangements for all types of ensembles, and multiple monthly magazines, translated into a need for more space. So in late February of 1914, Walter moved his company away from Tremont Street after two decades in the same block, over to 8 Bosworth Street, quadrupling his floor space. He also continued to hold warehouse space on Albany Street. His staff by that time consisted of nearly fifty people in a number of departments, including arrangers, engravers, printers, and clerical staff. By 1915 his catalog was so large that he put out a massive catalog, which was essentially index to over 100,000 alphabetically ordered arrangements of works for orchestra and band only, separate from his popular songs and piano instrumentals. He also expanded The Cadenza to include material for piano as well, and added the Jacobs Band Monthly to his list of periodicals published by the company. Circulation went beyond the United States, into Canada, England, Australia and New Zealand.

One interesting aspect of how widespread the effect of Jacobs' folios was around the country is mentioned in the autobiography of New Orleans traditional jazz bass player George Murphy "Pops" Foster. Written or dictated while in his final two years of life, there is some confusion evident in his memory, but some that can be rectified as well. One of those confusions may have been with a pianist named Walter Jacobs (there was also a blues harmonica player in later years), which is possibly a misidentification. He further remembered composer Tom Turpin as thin and not overly tall, which is hardly an apt description of the burly Saint Louis legend.

One of those confusions may have been with a pianist named Walter Jacobs (there was also a blues harmonica player in later years), which is possibly a misidentification. He further remembered composer Tom Turpin as thin and not overly tall, which is hardly an apt description of the burly Saint Louis legend.

One of those confusions may have been with a pianist named Walter Jacobs (there was also a blues harmonica player in later years), which is possibly a misidentification. He further remembered composer Tom Turpin as thin and not overly tall, which is hardly an apt description of the burly Saint Louis legend.

One of those confusions may have been with a pianist named Walter Jacobs (there was also a blues harmonica player in later years), which is possibly a misidentification. He further remembered composer Tom Turpin as thin and not overly tall, which is hardly an apt description of the burly Saint Louis legend.However, in context, Foster remembered that during the ragtime era in the 1910s, bandleaders such as Freddie Keppard and Joe "King" Oliver would "write away for numbers by Scott Joplin, Tom Turpin or Walter Jacobs. For a dollar you got four numbers. When we got a number nobody had, we'd cut the title off the sheet and write 'Some Stuff' up there and put a number on it to keep track of them. If a guy would ask what it was we'd say 'Some Stuff.' and that way he couldn't order a copy of it." From this description it is clear that Foster was remembering some of the many band arrangements put out in the Walter Jacobs folios, some of which were jazz oriented, or could easily be improvised upon.

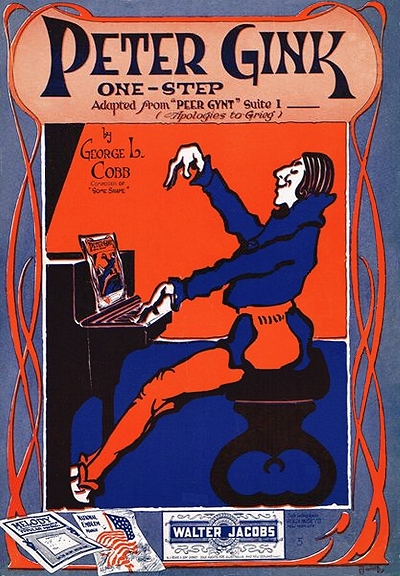

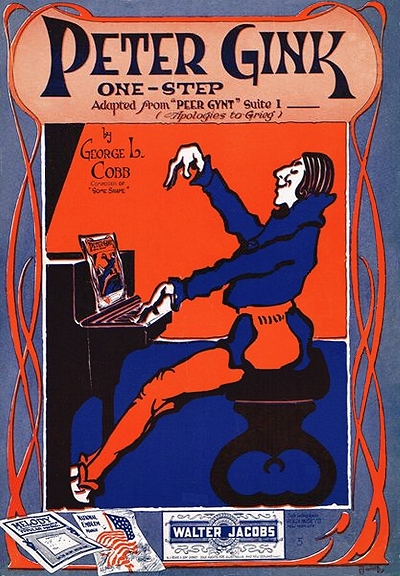

By the late summer of 1916 the need for more professional help to run the company resulted in Walter hiring banjoist C.V. Buttelman to oversee and edit his three existing magazines, and composer George L. Cobb, who had been doing very well with New York City and Chicago publishers, to both compose and edit publications. In that regard, Cobb, who had already enjoyed a number of fine hits, particularly "Dixie" numbers like Are You From Dixie and Alabama Jubilee, and a good piano rag output as well, would shine in his new position following his relocation to Boston. He would remain there for the remainder of his life, and worked for Jacobs for at least the next decade. In terms of hits for Jacobs, Cobb and his lyricist Jack Yellen turned the famous Our Director march by F.E. Bigelow, which had been acquired by Jacobs some years prior, into a rallying song for World War I. His Russian Rag (published in Chicago by Will Rossiter) would make waves throughout vaudeville and the country for some time, still performed frequently nearly a century later, as did his Peer Gynt parody, Peter Gink, published by Jacobs.

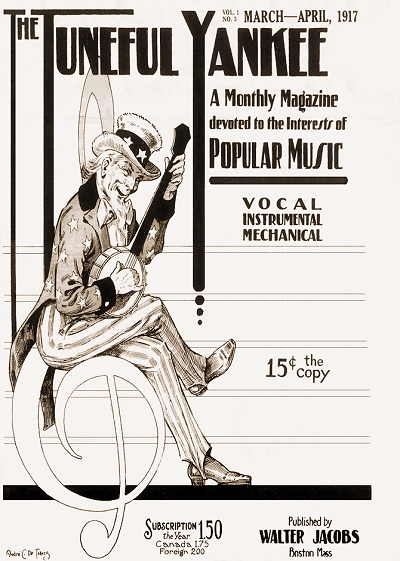

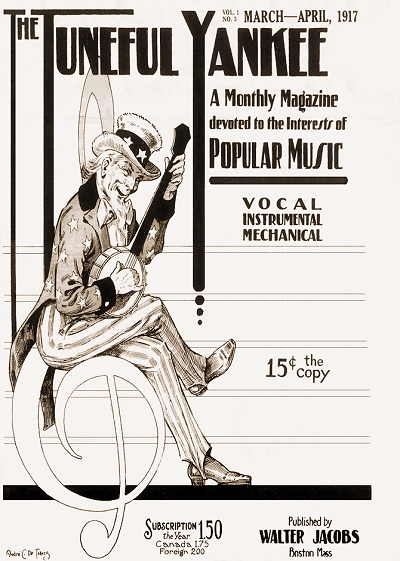

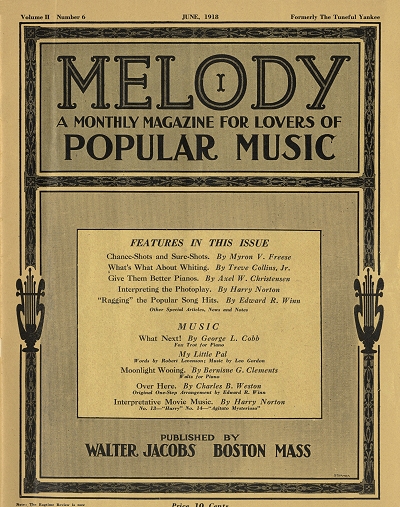

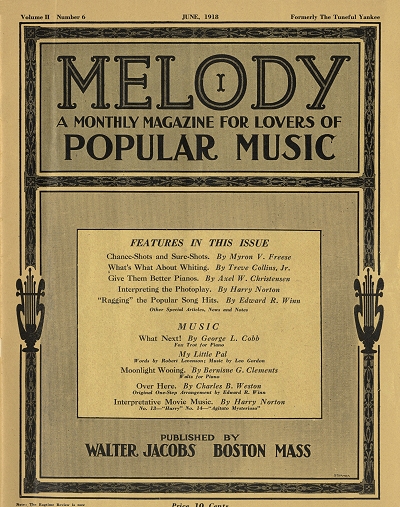

One of the important contributions that Cobb made to the Jacobs empire was the launching of a fourth periodical, The Tuneful Yankee, of which George was the primary editor and contributor. Premiering in January of 1917, its focus was more on the popular music output of the Jacobs organization than his other magazines. Cobb would comment, often times somewhat acerbic wit, on submissions made to the company, and some of his compositions plus entries he edited by others also made it into the monthly. In March of 1918, The Tuneful Yankee, which had enjoyed good circulation in the northeast, was recast as Melody Magazine, after having absorbed The Ragtime Review, which had been published by Chicago entrepreneur Axel S. Christensen. In reality, they appear to have bought the Review's mailing list, and went forward using essentially the same Jacobs staff, but expanded and with a new look. Cobb's most visible contribution to Melody Magazine was his column title "Just Between You and Me," which ironically was often a not-so-private venue for the occasional evisceration of amateur composers. If he thought something submitted to the magazine for analysis was tripe, Cobb had little trouble saying so. In spite of the sometimes negative vibe, Melody did quite well, particularly after the war, and the Jacobs company thrived.

Premiering in January of 1917, its focus was more on the popular music output of the Jacobs organization than his other magazines. Cobb would comment, often times somewhat acerbic wit, on submissions made to the company, and some of his compositions plus entries he edited by others also made it into the monthly. In March of 1918, The Tuneful Yankee, which had enjoyed good circulation in the northeast, was recast as Melody Magazine, after having absorbed The Ragtime Review, which had been published by Chicago entrepreneur Axel S. Christensen. In reality, they appear to have bought the Review's mailing list, and went forward using essentially the same Jacobs staff, but expanded and with a new look. Cobb's most visible contribution to Melody Magazine was his column title "Just Between You and Me," which ironically was often a not-so-private venue for the occasional evisceration of amateur composers. If he thought something submitted to the magazine for analysis was tripe, Cobb had little trouble saying so. In spite of the sometimes negative vibe, Melody did quite well, particularly after the war, and the Jacobs company thrived.

Premiering in January of 1917, its focus was more on the popular music output of the Jacobs organization than his other magazines. Cobb would comment, often times somewhat acerbic wit, on submissions made to the company, and some of his compositions plus entries he edited by others also made it into the monthly. In March of 1918, The Tuneful Yankee, which had enjoyed good circulation in the northeast, was recast as Melody Magazine, after having absorbed The Ragtime Review, which had been published by Chicago entrepreneur Axel S. Christensen. In reality, they appear to have bought the Review's mailing list, and went forward using essentially the same Jacobs staff, but expanded and with a new look. Cobb's most visible contribution to Melody Magazine was his column title "Just Between You and Me," which ironically was often a not-so-private venue for the occasional evisceration of amateur composers. If he thought something submitted to the magazine for analysis was tripe, Cobb had little trouble saying so. In spite of the sometimes negative vibe, Melody did quite well, particularly after the war, and the Jacobs company thrived.

Premiering in January of 1917, its focus was more on the popular music output of the Jacobs organization than his other magazines. Cobb would comment, often times somewhat acerbic wit, on submissions made to the company, and some of his compositions plus entries he edited by others also made it into the monthly. In March of 1918, The Tuneful Yankee, which had enjoyed good circulation in the northeast, was recast as Melody Magazine, after having absorbed The Ragtime Review, which had been published by Chicago entrepreneur Axel S. Christensen. In reality, they appear to have bought the Review's mailing list, and went forward using essentially the same Jacobs staff, but expanded and with a new look. Cobb's most visible contribution to Melody Magazine was his column title "Just Between You and Me," which ironically was often a not-so-private venue for the occasional evisceration of amateur composers. If he thought something submitted to the magazine for analysis was tripe, Cobb had little trouble saying so. In spite of the sometimes negative vibe, Melody did quite well, particularly after the war, and the Jacobs company thrived.Part of the period during World War I was a bit problematic for Jacobs, as he lost some of his leading employees to the war effort, including the head of his shipping department, somewhat lessening the efficiency of his company's output while others worked to learn his duties. He returned just after the war. He also hired publishing assistant Louis Zuker in late 1918 to assist with the growing scope of the Jacobs magazine publications. Around the same time, in December of 1918, Walter was elected as the secretary and treasurer of the Boston Music Publishers' Association. He held that position for a year, but resigned at the annual meeting in December of 1919, "entirely due to the pressure of work," according to the MTR of December 27.

The 1920s saw continued emphasis on the magazine output of the Jacobs company, and an increased presence in photoplay music, or folios geared toward film pianists. These important works, also put out by Jerome H. Remick and Sam Fox, contained a number of short to mid-sized musical strains for both piano and small ensembles, intended to cover all types of moods, ethnic cultures, historical scenes and specific incident types, so that less creative pianists, organists, or even various-sized ensembles who did not want to create custom scores for films twice a week would be able to quickly assemble something for whatever film was currently playing, or at least inspire ideas for it. Between 1909 and the late 1920s, the company ultimately put out more than 100 folios covering various instrumentations, some focused on certain genres. Some of the cues appeared in Melody Magazine into the mid-1920s. Cobb was a frequent contributor to these folios, along with another staff writer, British-born composer Richard E. Hildreth. Both had continued to write for Melody as well, using a variety of pseudonyms to imply a larger stable of composers as contributors.

Between 1909 and the late 1920s, the company ultimately put out more than 100 folios covering various instrumentations, some focused on certain genres. Some of the cues appeared in Melody Magazine into the mid-1920s. Cobb was a frequent contributor to these folios, along with another staff writer, British-born composer Richard E. Hildreth. Both had continued to write for Melody as well, using a variety of pseudonyms to imply a larger stable of composers as contributors.

Between 1909 and the late 1920s, the company ultimately put out more than 100 folios covering various instrumentations, some focused on certain genres. Some of the cues appeared in Melody Magazine into the mid-1920s. Cobb was a frequent contributor to these folios, along with another staff writer, British-born composer Richard E. Hildreth. Both had continued to write for Melody as well, using a variety of pseudonyms to imply a larger stable of composers as contributors.

Between 1909 and the late 1920s, the company ultimately put out more than 100 folios covering various instrumentations, some focused on certain genres. Some of the cues appeared in Melody Magazine into the mid-1920s. Cobb was a frequent contributor to these folios, along with another staff writer, British-born composer Richard E. Hildreth. Both had continued to write for Melody as well, using a variety of pseudonyms to imply a larger stable of composers as contributors.From the 1910s into the 1920s, Jacobs, now in his fifties, started to back off from his primary leadership role in the company, and of the duties were taken over by Buttelman, who became the face of the company, at least within the publishing industry. However, in 1924 Buttelman was lured away by the Gibson musical instrument company of Kalamazoo, Michigan, to become their advertising and sales manager for a time. He returned to Jacobs in late 1925, as the publisher relocated to new slightly larger quarters at 120 Boylston Street that September. He also subleased both space and services to a number of other publishers and music-related firms in the city. Buttelman continued to run the company into the early part of the Great Depression. Cobb also left the company around 1926 to pursue some of his own interests and care for his recently-widowed mother. Melody Magazine ceased publication not too long after Cobb's departure. Jacobs remained active in the publishing community, however, serving on the board of the Music Publishers' Association of the United States during the mid to late 1920s. He also never forgot how he got his start, continuing his supply of musical arrangements for plucked-string instruments, particularly the ukulele, which had experienced enormous popularity throughout the 1920s.

In late June of 1930, C.V. Buttelman announced his resignation from his post of vice president of the Jacobs company, this time for good. With him, and also due to the ongoing Great Depression that found many musicians lacking the funds necessary to subscribe, the Orchestra and Band monthlies all but died out in a short time. The 1930 census showed Walter lodging with his bookkeeper Sarah Daniels and her extended family in Somerville, Massachusetts, listed as the manager of his publishing company. In Somerville directories of the 1930s into the 1940s, as well as the 1940 Federal census, Walter listed himself as the general manager of his music publishing house, and continued to board with his bookkeeper Sarah Daniels in the David C. Smith family home. However, the company was a mere shadow of its former self by the mid-1930s, having been ravaged like much of the music industry by the financial hardships of the time. Much of their output from that period was in the form of folios and publications focused on school bands and orchestras, including works for stringed instruments, and some of their most successful copyrights, including the early marches he had acquired. However, Walter did bolster his catalog of that time by buying out both the Virtuoso School of Music of Buffalo, New York, in 1933, and the Mace Gay catalog in 1934, both comprised largely of method books and marches.

Jacobs' last listing as a publisher was found in the 1941 Boston city directory, after which it appears that his assets were sold off to other companies. Walter Jacobs passed on in Somerville, Massachusetts, in the spring of 1945, leaving behind a wealth of published music that is still played, and some of it even in print a century later.

Thanks to performer Todd Robbins for pointing out the interesting information in the Pops Foster autobiography, adding some color to the story.

Published Composers

Published Composers