George Gershwin (George Bruskin Gershvin) (September 26, 1898 to July 11, 1937) | |

Instrumental Compositions Instrumental Compositions | |

|

c.1914

TangoRagging the Traumeri 1917

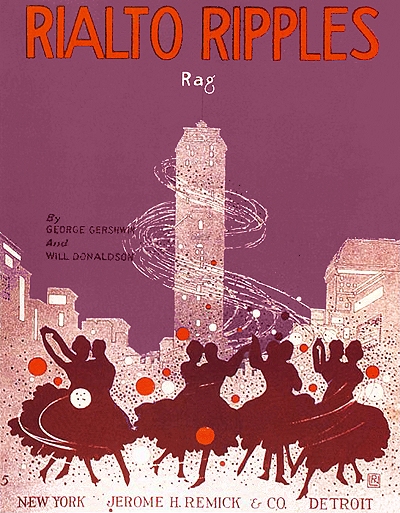

Rialto Ripples [1]1919

Lullaby (A String Quartet)Novelette in Fourths c. mid-1920s

Three Quarter Blues (Irish Waltz)1923

Rubato (Novelette-Prelude)1924

Rhapsody in Blue1925

Short Story (Novelette)Sleepless Night Concerto in F 1. Allegro 2. Adagio - Andante con moto 3. Allegro Agitato 1926

Three Preludes for Piano1. Bbm - Allegro 2. C#m - Andante (Blue Lullaby) 3. Ebm - Allegro (Spanish Prelude) 1928

An American in ParisMerry Andrew 1929

Impromptu in Two Keys (Yellow Blues)1931

Second Rhapsody |

1932

Cuban Overture (a.k.a. Rumba)Piano Transcriptions of Eighteen Songs 1. Swanee 2. Somebody Loves Me 3. My One and Only 4. Who Cares 5. I'll Build a Stairway to Paradise 6. The Man I Love 7. Strike Up the Band 8. Sweet and Low Down 9. Do It Again 10. Fascinatin' Rhythm 11. 'S Wonderful 12. Oh, Lady Be Good 13. Do-Do-Do 14. Nobody But You 15. That Ceratin Feeling 16. Clap Yo' Hands 17. Liza 18. I Got Rhythm 1933

Two Waltzes in C1934

Variations on "I Got Rhythm"1936

Catfish Row Suite from Porgy and Bess1. Catfish Row 2. Porgy Sings 3. Fugue 4. Hurrican 5. Good Morning, Brother 1937

Promenade (a.k.a. Walking the Dog) |

Popular Songs/Broadway Shows Popular Songs/Broadway Shows | |

|

1916

When You Want 'Em, You Can't Get 'Em(When You've Got 'Em, You Don't Want 'Em) [2] The Passing Show of 1916: Revue The Making of a Girl [3,4] My Runaway Girl [2] 1917

Gush-Gush-Gushing [5]When There's a Chance to Dance [5] When the Armies Disband [6] A Good Little Tune [6] Beautiful Bird [7] We're Six Little Nieces of our Uncle Sam [7] 1918

Hitchy-Koo of 1918You-oo, Just You [6] Ladies First: Musical The Real American Folk Song Is a Rag [5] Some Wonderful Sort of Someone [8] Half Past Eight: Musical There's Magic in The Air [5] The Ten Commandments of Love [9] Cupid [9] Hong Kong [9] 1919

Oh Land of Mine, America [12]Good Morning Judge: Musical I Was So Young (You Were So Beautiful) [6,13] Lady in Red: Musical Something About Love [7] Capitol Revue: Musical Swanee [6] Come to the Moon [7,14] La, La, Lucille 1919: Musical [10,11] Kindly Pay Us When You Live in a Furnished Flat The Best of Everything From Now On Money, Money, Money! Tee-Oodle-Um-Bum-Bo Nobody But You Hotel Life (Oo, How) I Love to Be Loved By You [7] It's Great to Be in Love There's More to the Kiss than the Sound [X-X-X] [6] Somehow It Seldom Comes True The Ten Commandments of Love Our Little Kitchenette † The Love of a Wife † Kisses † Morris Gest's Midnight Whirl: Revue [10,15] I'll Show You a Wonderful World The League of Nations (Depends on Beautiful Clothes) Doughnuts Poppyland Limehouse Nights Aphronightie (Parody on Fokine's Bacchanal from Aphrodite) Let Cutie Cut your Cuticle Baby Dolls East Indian Maid Dere Mabel: Musical [6] We're Pals Back Home I Don't Know Why (When I Dance with You) 1920

Yan-Kee [6]George White's Scandals of 1920: Revue [11] My Lady Everybody Swat the Profiteer On My Mind the Whole Night long Scandal Walk Tum On and Tiss Me The Songs of Long Ago Idle Dreams The Lattice Room Number My Old Love is My New Love The Sweetheart Shop: Musical Waiting for the Sun to Come Out [5] Broadway Brevities of 1920: Musical Spanish Love [6] Love Me While the Snowflakes Fall [11] I'm a Dancing Fool [11] Lu-Lu [11] Ed Wynn's Carnival: Musical Oo, How I Love You to be Loved by You [7] 1921

Molly on the Shore [5]Phoebe [5,7] [Unpublished] Swanee Rose (a.k.a. Dixie Rose) [6,10] Tamalé (I'm Hot for You) [10] In the Heart of a Geisha (Nippo San of Japan) [16] Blue Eyes: Musical Wanting You [6] From Piccadilly to Broadway: Revue Something Peculiar [5,7] Snapshots of 1921: Revue On the Brim of Her Old-Fashioned Bonnet [17] Baby Blues [17] Futuristic Melody [17] The Broadway Whirl: Musical [10,15,18,19,20] From the Plaza to Madison Square Button Me Up the Back Three Little Maids Poppy Land [10,15] Lime House Nights [10,15] Stars of Broadway The Husband, The Wife and Lover A Dangerous Maid Boy Wanted [5] Just to Know You are Mine [5] Some Rain Must Fall [5] The Simple Life [5] The Sirens † George White's Scandals of 1921: Revue [11] I Love You South Sea Isles (Sunny South Sea Islands) Mother Eve Where East Meets West Drifting Along with the Tide (She's) Just a Baby The Perfect Fool: Musical No One Else But that Girl of Mine [6] My Log Cabin Home [6,10] For Goodness Sake: Musical Someone [21] Tra-La-La [21] 1922

The Flapper [10,22]The French Doll: Musical Do it Again [10] For Goodness Sake: Musical Someone [21] Tra-La-La [21] All To Myself [21] George White's Scandals of 1922: Revue [10,17] Little Cinderlatives (Oh, See What) She Hangs Out in Our Alley (My Heart Will Sail) Across the Seas I Found a Four Leaf Clover I'll Build a Stairway to Paradise Argentina Little Cinderlatives I Can't Tell Where They're From When They Dance Just a Tiny Cup of Tea Where is the Man of My Dreams? You Can Tell Who We Are by the Things That We Have Done Blue Monday (Miniature Opera) [10] Overture Prologue: Ladies and Gentlemen Blue Monday Blues (a.k.a. 135th Street Blues) Has Anyone Seen My Joe? Monday's the Day That All the Earthquakes Quiver I'll Tell the World I Did I'm Gonna See My Mother Spice of 1922: Revue The Yankee Doodle Blues [6,10] Our Nell: Musical [22,23,24] Gol-Durn! Innocent Ingenue Baby Old New England Home The Cooney County Fair Names I Love to Hear By and By Madrigal We Go to Church on Sunday Walking Home with Angeline Oh, You Lady! (All the) Little Villages The Custody of the Child † 1923

The Dancing Girl: MusicalThat American Boy of Mine [6] Why Am I So Sad [3] Cuddle Up [3] Pango Pango [3] The Rainbow: Musical [25] Sweetheart (I'm So Glad I Met You) Good-Night, My Dear Any Little Tune Moonlight in Versailles In the Rain Innocent Lonesome Blue Baby [22,24,25] Beneath the Eastern Moon Oh! Nina Strut Lady with Me Sunday in London Town George White's Scandals of 1923: Revue [10] Little Scandal Dolls You and I [26] Katrinka There is Nothing Too Good for You [10,17] Throw Her in High [10,17] Let's Be Lonesome Together [10,17] Lo-La-Lo The Life of a Rose Look in the Looking Glass Where is She? (On the Beach) How've You Been? Laugh Your Cares Away Little Miss Bluebeard: Musical I Won't Say I Will (But I Won't Say I Won't) [5,10] The Sunshine Trail: Musical The Sunshine Trail [5] Nifties of 1923: Musical Nashville Nightingale [6] At Half-Past Seven [10] 1924

Sweet Little Devil: Musical [10]Strike, Strike, Strike Virginia, (Don't Go Too Far) Someone Who Believes in You System The Jijibo Quite a Party Under a One-Man Top The Matrimonial Handicap Just Supposing Hey! Hey! (Let 'Er Go!) The Same Old Story Mah Jongg Hooray for the U.S.A. Pepita Be the Life of the Crowd † You're Might Lucky, My Little Ducky † Sweet Little Devil † George White's Scandals of 1924: Revue [10,27] Just Missed the Opening Chorus I'm Going Back (I Need) A Garden (Night Time in) Araby Somebody Loves Me Year After Year We're Together Tune in (to Station J.O.Y.) Rose of Madrid I Love You My Darling Kong Kate Lovers of Art Primrose [28] Leaving Town While We May The Countryside Boy Wanted [5,28] This Is the Life for a Man When Toby is Out of Town Some Far-Away Someone [5,10] The Mophams I'll Have a House in Berkely Square (Isn't It Terrible What they Did to) Mary Queen of Scots Wait a Bit, Susie [5,28] Naughty Baby [5,28] Primrose Ballet Till I Meet Someone Like You That New Fangled Mother of Mine I Make Hay when the Moon Shines Isn't it Wonderful! [5,28] Roses of France Berkely Square and Kew Can We Do Anything? [5,28] Four Little Sirens Beau Brummel Lady Be Good: Musical [5] Seeing Dickie Home Hang on to Me A Wonderful Party The End of a String We're Here Because Fascinating Rhythm The Robinson Hotel So Am I Oh, Lady Be Good The Half of it Dearie Blues Juanita Leave It to Love Little Jazz Bird Carnival Time Swiss Miss [5,11] The Man I Love † Evening Star † Will You Remember Me? † The Bad, Bad Men † Weatherman/Rainy Afternoon Girls † Singin' Pete † Laddie Daddie † 1925

Tell Me More: Musical [5,10]Tell Me More! Mr. and Mrs. Sipkin When the Debbies Go By Three Times a Day Why Do I Love You? How Can I Win You Now? Kickin' the Clouds Away Love Is in the Air My Fair Lady In Sardinia Baby! The Poetry of Motion Ukulele Lorelei Oh, So 'La' Mi Murderous Monty (and Light-Fingered Jane) [28] [London production only] Love, I Never Knew [28] [London production only] Shop Girls and Mannikins [sic] [Unusued] I'm Something on Avenue A [Unusued] The He-Man [Unusued] Tip-Toes: Musical [5] Waiting for the Train Nice Baby! (Come to Papa!) Looking for a Boy Lady Luck When Do We Dance? These Charming People That Certain Feeling Sweet and Low Down Our Little Captain Harbor of Dreams It's a Great Little World Nightie-Night Tip-Toes Harlem River Chanty † Gather Ye Rosebuds † We † Dancing Hour † Life's Too Short to Be Blue † Song of the Flame: Musical [29,30,31] Far Away Song of the Flame (Don't Forget Me) A Woman's Work is Never Done Great Big Bear The Signal Cossack Love Song (Don't Forget Me) Tar-Tar (You May) Wander Away Finaletto Vodka Finale I Want Two Husbands You Are You Midnight Bells The First Blossom Ballet Going Home on New Year's Morning Finale Ultimo 1926

Oh, Kay!: Musical [5]The Woman's Touch Don't Ask! Dear Little Girl (I Hope You've Missed Me) Maybe Clap Yo' Hands Do, Do, Do Bride and Groom Someone to Watch Over Me Fidgety Feet Heaven on Earth Oh, Kay! What's the Use † When Our Ship Comes Sailng In † Bring on the DIng Dong Bell † Guess Who † Isn't It Romantic † The Moon is on the Sea † The Sun is on the Sea † Americana: Revue That Lost Barber Shop Chord [5] Lady Be Good: Musical [London production only] I'd Rather Charleston [28] Buy a Little Button from Us [28] 1927

Strike Up the Band: Musical (Original) [5]* Denotes numbers cut or revised in 1930 Fletcher's American Cheese Choral Society * Seventeen and Twenty-One * A Typical Self-Made American Meadow Serenade * A Man of High Degree The Unofficial Spokesman Patriotic Rally * Three Cheers for the Union This Could Go On for Years The Man (Girl) I Love * Yankee Doodle Rhythm * Finaletto Act 1 |

1927 (Cont)

Strike Up the BandOh, This is Such a Lovely War * Hoping That Someday You'd Care * Military Dancing Drill How About A Boy? How About A Man Like Me? * Finaletto Act 2 Homeward Bound The Girl I Love * The War That Ended the War * Finale Funny Face: Musical [5] We're All A-Worry, All Agog When You're Single Those Eyes Birthday Party Once Funny Face High Hat 'S Wonderful Let's Kiss and Make Up Come Along, Let's Gamble If You Will Take Our Tip He Loves and She Loves Tell the Doc My One and Only (What Am I Gonna Do?) Sing a Little Song In the Swim The World Is Mine The Babbitt and the Bromide Dance Alone With You Acrobats † When You Smile † Aviator † Blue Hullabaloo † 1928

Rosalie: Musical [4,5,32]Show Me the Town Here They Are Entrace of the Hussars Hussar March Say So! Let Me Be a Friend to You West Point Bugle Oh Gee!-Oh Joy! Kingdom of Dreams New York Serenade The King Can Do No Wrong Ev'rybody Knows I Love Somebody [5] How Long Has This Been Going On? Setting-Up Exercises At the Ex-Kings' Club The Goddesses of Crystal The Ballet of the Flowers Rosalie † Beautiful Gypsy † When Cadets Parade † Follow the Dream † I Forgot What I Wanted to Say † You Know How it Is † Treasure Girl: Musical [5] Skull and Bones (I've Got a) Crush on You I Don't Think I'll Fall in Love Today Oh, So Nice According to Mr. Grimes Got a Rainbow Feeling I'm Falling Place in the Country K-ra-zy for You What Are We Here For? Where's the Boy? Here's the Girl! I Want to Marry a Marionette † This Particular Party † What Causes That? † Treasure Island † Dead Me Tell No Tales † Good-Bye to the Old Love, Hello to the New † A-Hunting We Will Go † 1929

Show Girl [5,33]Happy Birthday My Sunday Fella How Could I Forget Lolita? Lolita (My Love) Do What You Do! Spain One Man So Are You! I Must Be Home by Twelve O'Clock Black and White Harlem Serenade An American in Paris (Blues Ballet) Home Blues Follow the Minstrel Band Liza (All the Clouds'll Roll Away) Feeling Sentimental † Home Lovin' Gal/Man † Adored One † Tonight's the Night! † I'm Just a Bundle of Sunshine † At Mrs. Simpkin's Finishing School † Someone's Always Calling a Rehearsal † I Just Looked at You † I'm Out For No Good Reason Tonight † Minstrel Show † Somebody Stole My Heart Away † In the Mandarin's Orchid Garden [5] † 1930

Strike Up the Band: Musical (Revised) [5]* Denotes numbers added or revised from 1927 Fletcher's American Chocolate Choral Society Workers * Seventeen and Twenty-One (I Mean to Say) * A Typical Self-Made American Soon * A Typical Self-Made American A Man of High Degree The Unofficial Spokesman Three Cheers for the Union! This Could Go On for Years If I Became President * (What's the Use) Hangin' Around with You?* He Knows Milk * Strike Up the Band In the Rattle of the Battle * Military Dancing Drill Mademoiselle from New Rochelle * I've Got a Crush on You * (How About a Boy) Like Me? * I Want to Be a War Bride * The Unofficial March of General Holmes * Official Resume: First There Was Fletcher * Ring a Ding Dong Bell (Ding Dong) * Finale Girl Crazy: Musical [5] Bidin' My Time The Lonesome Cowboy Could You Use Me? Broncho Busters Barbary Coast Embraceable You Goldfarb, That's I'm! Sam and Delilah I Got Rhythm Land of the Gay Caballero But Not for Me Treat Me Rough Boy! What Love Has Done to Me (When It's) Cactus Time in Arizona The Gambler of the West † And I Have You † You Can't Unscramble Scrambled Eggs † Nine-Fifteen Revue: Revue Toddlin' Along [5] 1931

Delicious: Musical Film [5]Delishious Welcome to the Melting Pot Somebody from Somewhere Katinkitschka You Started It Dream Sequence Blah, Blah, Blah Rhapsody in Rivets (Manhattan Rhapsody) Thanks to You † Mischa, Yascha, Toscha, Sascha [21] † Of Thee I Sing: Musical [5] Wintergreen for President Who is the Lucky Girl to Be? The Dimple on My Knee Because, Because As the Chairman of the Committee How Beautiful Never Was There a Girl So Fair Some Girls Can Bake a Pie Love is Sweeping the Country Of Thee I Sing (Here's) A Kiss for Cinderella I Was the Most Beautiful Blossom Hello, Good Morning Who Cares? (So Long as You Care for Me) Garcon, S'il vous plait The Illegitimate Daughter The Senatorial Roll Call Jilted We'll Impeach Him I'm About to Be a Mother (Who Could Ask for Anything More?) Posterity is Just Around the Corner Trumpter, Blow Your Golden Horn On That Matter No One Budges Call Me Whate'er You Will † 1932

Girl Crazy: Musical Film (Added Song)You've Got What Gets Me [5] 1933

Till Then [5]Pardon My English: Musical [5] In Three Quarter Time Lorelei Pardon My English Dancing in the Streets So What? Isn't It a Pity Drink, Drink, Drink My Cousin in Milwaukee Hail the Happy Couple The Dresden Northwest Mounted Luckiest Man in the World What Wort of Wedding is This? Tonight Where You Go, I Go I've Got to Be There He's Not Himself Fatherland, Mother of the Band † Freud and Jung and Adler † Together at Last † Bauer's House † Poor Michael, Poor Golo † Let 'Em Eat Cake: Musical [5] Wintergreen for President Tweedledee for President Union Square Down With Everyone That's Up Shirts by the Millions Comes the Revolution Mine Climb Up the Social Ladder Cloistered from the Noisy City What More Can a General Do On and On and On Double Dummy Drill I've Brushed My Teeth The General's Gone to a Party All the Mothers of the Nation Yes, He's a Bachelor There's Something We're Worried About What's the Proletariat Let 'Em Eat Cake Blue, Blue, Blue Who's the Greatest No Comprenez, No Capish, No Versteh! Why Speak of Money? No Better Way to Start a Case Up and At 'Em! On to Victory Oyez, Oyez, Oyez Play Ball When the Judges Doff the Ermine That's What He Did I Know a Foul Ball Throttle Throttlebottom A Hell of a Hole (A Hell of a Fix) Down With Everyone Who's Up It Isn't What You Did Let 'Em Eat Caviar Hang Throttlebottom in the Morning First Lady and First Gent † 1935

Porgy and Bess: Musical/Opera [5,34]Prelude - Catfish Row Summertime A Woman is a Sometime Thing Street Cry (Honey Man) They Pass By Singing Crap Game Fugue (Oh Little Stars) Crown and Robbins' Fight Gone, Gone, Gone Overflow My Man's Gone Now Leavin' 'fo' de Promis' Lan' It Takes a Long Pull to Get There I Got Plenty O' Nuttin' Woman to Lady Bess, You Is My Woman Now Oh I Can't Sit Down It Ain't Necessarily So What You Want With Bess? Time and Time Again Street Cries (Strawberry Woman, Crab Man) I Loves You, Porgy Hurricane Oh de Lawd Shake de Heaven A Red Headed Woman Oh, Doctor Jesus Clara, Don't You Be Downhearted There's a Boat That's Leavin' Soon for New York Oh Bess, Where's My Bess I'm On My Way Buzzard Song † Lonesome Boy † I Ain't Got No Shame † Jazzbo Brown Blues † I Hate's Yo' Struttin' Style † Oh, Heavn'ly Father (Six Prayers) † Occupational Humoresque † 1936

The King of Swing [35]Doubting Thomas [35] Strike Up the Band for UCLA [5] The Show is On: Musical By Strauss [5] 1937

Shall We Dance: Musical Film [5]Shall We Dance? (I've Got) Beginner's Luck Watch Your Step Let's Call the Whole Thing Off Walking the Dog (a.k.a. Promenade) They Can't Take That Away From Me Slap That Bass They All Laughed Wake Up, Brother, and Dance † Hi-Ho! At Last † A Damsel in Distress: Musical Film [5] A Foggy Day (In London Town) I Can't Be Bothered Now Put Me to the Test Stiff Upper Lip Nice Work if You Can Get It Things Are Looking Up The Jolly Tar and the Milkmaid Sing of Spring Pay Some Attention to Me † 1938 (Posth)

Dawn of a New Day [5] (Song of the 1939New York World's Fair) The Goldwyn Follies: Musical Film [5] Love Is Here to Stay I Was Doing All Right Spring Again Love Walked In I Love to Rhyme Just Another Rhumba † Exposition: Idea for a Ballet † [5,36] 1946 (Posth)

The Shocking Miss Pilgrim: Musical Film [5]Changing My Tune Stand Up and Fight Aren't You Kind of Glad We Did? The Back Bay Polka One, Two, Three Waltzing is Better Sitting Down Demon Rum For You, For Me, For Evermore Sweet Packard Welcome Song Tour of the Town † 1964 (Posth)

Kiss Me Stupid: Musical Film [5]I'm a Poached Egg All the Livelong Day (and the Long, Long Night) Sophia

1. w/Will Donaldson

2. w/Murray Roth 3. w/Harold Atteridge 4. w/Sigmund Romberg 5. w/Ira Gershwin 6. w/Irving Caesar 7. w/Lou Paley 8. w/Schuyler Greene 9. w/Edward B. Perkins 10. w/Buddy Gard (B.G.) DeSylva 11. w/Arthur J. Jackson 12. w/Michael E. Rourke 13. w/Alfred Bryan 14. w/Ned Wayburn 15. w/John Henry Mears 16. w/Fred Fischer 17. w/E. Ray Goetz 18. w/Harry Tierney 19. w/Joseph McCarthy 20. w/Richard Carle 21. w/Ira Gershwin as Arthur Francis 22. w/William Daly 23. w/A.E. Thomas 24. w/Brian Hooker 25. w/Clifford Grey 26. w/Jack Green 27. w/Ballard Macdonald 28. w/Desmond Carter 29. w/Herbert P. Stothart 30. w/Otto Harbach 31. w/Oscar Hammerstein II 32. w/Pelham Grenville (P.G.) Wodehouse 33. w/Gus Kahn 34. w/DuBose Heyward 35. w/Al Stillman 36. w/George Balanchine † Dropped from or Unused in a Show |

Few composers of any century, much less the 20th century, were as productive or creative as George Gershwin, a true American treasure. While his semi-meteoric rise was not quite an overnight success, it was well deserved and was achieved with determination, talent, and little hesitation. Within a life span only a little longer than that of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Gershwin revolutionized and even codified the relationship between popular songs and the Broadway stage, carrying along with him his friends Irving Berlin and Cole Porter in the process. In fact, given the spread of styles he covered, it is hard to pigeonhole Gershwin's music into any predefined genre, suggesting in some cases that his style was a genre unto itself. His was also a similar story to some of his composer peers who came out of the immigrant neighborhoods to rise to the pinnacle of fame in the growing entertainment industry.

Early Years

George was the second of four children born to Russian immigrants Morris Gershovitz (arrived 1891) and Rose (Bruskin) Gershovitz (arrived 1892), who were married on July 21, 1895. Also in the family were his older brother and eventual lyricist Isadore (12/6/1896), younger brother Arthur (3/14/1900), and younger sister Frances (12/6/1906), born exactly a decade after her oldest brother. Morris' brother Aaron had also immigrated around the same time and was living nearby. Most available sources claim that George was born as Jacob Gershovitz on September 26, 1898. There are a couple of official documents that challenge those points and explanations to support the likely circumstances.

Gershwin's birth certificate (#14691) has a date of September 26 and the name Jacob Bruskin Gershwine, but with the correct parents listed so it is his. George's 1917 draft record claims a birth date of September 25, which is written in his own hand.

Was he misinformed as a child or did the attending doctor write the wrong date as well as a misspelled last name? It could also be due to the Jewish tradition of not recognizing the new day until sunset, and George was born mid-day. What seems less of an error is that on the 1900 Census taken June 7, 1900, when he was less than 21 months old, he is clearly listed as George Gershvin (could be Gershwin), not Jacob Gershovitz or Gershwine. The same goes for his older brother Ira, shown as Israel Gershovitz on his birth certificate (#53973), but who was consistently referred to after his birth variously as Ysidore, Isidore or Isadore.

|

One possible explanation of the variance goes to poor communication between the doctor or staff and the parents when the birth certificate was filled out. Another more viable explanation is that many American immigrant Jewish families had two different names for their children - one in Yiddish, and the other an Anglicized version. This may be the case with George whose Yiddish name may well have been Jacob, as much as Isadore's was Israel. However, it appears that George is the only name he ever knew or went by. On the family name: Isadore was born with the name Gershovitz. Therefore Morris or his brother Aaron simplified or Anglicized the family name sometime between the births of their first two boys. On most available sources it appears variously as Gershvin or Gershwin throughout the early 1900s. In any case, he was never George Gershovitz.

The Gershwin household was a mobile one, sometimes moving as many as three times in a year, as Morris evidently liked to live near his constantly changing place of business. When George was born he was said to have been in leather. By 1900 he was listed as a shoemaker, which may have been an offshoot of the leather business. He dabbled in other areas of clothing, retail, bookmaking, and even running a Turkish bath, as more of his immigrant peers were flooding the lower East Side of Manhattan and over into Brooklyn, the family bouncing back and forth between each borough. This instability may have affected George, even more so than his brother Izzy, as the youth did not fare well in school. While capable, he was distracted and showed little interest in sitting in class much less learning. In spite of his slight build, George was athletic and preferred to be out roller skating or playing at some other sport. It was clear that Izzy would be the studious one who would achieve the American dream. That is, if not for Max Rosenzweig.

Maxie was one of George's younger school friends and at ten years old becoming a fine violinist as well (he had a fine career with the instrument as virtuoso Max Rosen).

The family also had a piano (some sources report it was a player piano, but this is hard to verify), for which George quickly discovered his aptitude and learned to play a few popular ragtime melodies over a period of perhaps two years from 1909 to 1910. Then one day at the Gershwin household, it was decided that Izzy was to receive a piano and lessons for his 12th birthday, given the potential for his musical talent from the perspective of Rose. His parents bought a new Knabe upright piano from dealer George Hochman on time payments. After it was lifted up several floors and through a window into their flat, it is possible that Izzy reluctantly picked at it a bit, and then George sat down and amazed the family at what he already knew on the instrument. (In fact, it is likely that Rose had already heard him play at Max's house.) While both took lessons for a while, it was George who continued with the lessons while a relieved Izzy looked in other directions for something to fit his talents. Frances also received some musical training in voice at an early age. In general, Frances and Arthur were in many ways removed from their older siblings, and shared only a passing relationship according to some biographies. As of the 1910 Census the family is shown living in Manhattan with Morris running an unspecified business. The family also had a live-in servant, Ida Beckowitz, so business must have been good.

|

School was tough enough on George. Being surrounded by ragtime and popular songs while taking lessons in classical music was even more frustrating. His first two teachers were Miss Green and an unnamed Hungarian band director. However, after more than two years George had outgrown their patience and skills, and needed something more. Having been playing in a few public locations, he was befriended by pianist Jack Miller who in turn introduced George to Charles Hambitzer. The instructor would become George's mentor over the next four or so years (he died in 1918), and would go beyond technique, giving Gershwin a new perspective on European composers including contemporaries such as Ravel and Debussy. He also encouraged George to attend symphonic concerts featuring piano, which must have given the boy a taste for the stage as well as some excitement about the scope of such works. Hambitzer further directed George to Edward Kilenyi for additional lessons in theory and composition as time and money permitted. Around the same time, determined to pursue a music career, George quit high school with his mother's blessing and understanding, and tried to find work either playing or working for a publisher. Sister Frances was also becoming adept at singing and dance, and actually may have preceded her older brother in earning money through music. However, she married very young and gave up music and dance for painting and motherhood.

From Tin Pan Alley to Broadway

After searching around a bit, George managed to get hired by Mose Gumble as a song plugger at the publishing house of Jerome H. Remick for $15.00 per week.  This meant that he would play new songs for potential customers, often producers or stage singers, in poorly insulated cubicles amidst a sea of other pianos. However, it did earn him some income, and it inspired George to write some as well. He also found some work arranging and playing piano rolls of ragtime and popular songs for Standard Music Rolls at Perfection Studios in East Orange, New Jersey. With another friend, Murray Roth, George composed When You Want 'Em, You Can't Get 'Em (When You've Got 'Em, You Don't Want 'Em), a clever ragtime tune with an unwieldy title. Gumble and others at Remick showed no interest, with Gumble having to admonish Gershwin, saying "You're here as a pianist, not a writer. We've got plenty of writers under contract." The pair ended up selling it to Harry Von Tilzer based on some urging by singer Sophie Tucker, with Roth accepting $15 up front, but George holding out for royalties. He eventually received a mere $5 from Von Tilzer after asking for at least something. George also committed to piano roll for Standard at one of his Saturday recording sessions, becoming only a moderate seller. But George Gershwin was now a song writer at only seventeen.

This meant that he would play new songs for potential customers, often producers or stage singers, in poorly insulated cubicles amidst a sea of other pianos. However, it did earn him some income, and it inspired George to write some as well. He also found some work arranging and playing piano rolls of ragtime and popular songs for Standard Music Rolls at Perfection Studios in East Orange, New Jersey. With another friend, Murray Roth, George composed When You Want 'Em, You Can't Get 'Em (When You've Got 'Em, You Don't Want 'Em), a clever ragtime tune with an unwieldy title. Gumble and others at Remick showed no interest, with Gumble having to admonish Gershwin, saying "You're here as a pianist, not a writer. We've got plenty of writers under contract." The pair ended up selling it to Harry Von Tilzer based on some urging by singer Sophie Tucker, with Roth accepting $15 up front, but George holding out for royalties. He eventually received a mere $5 from Von Tilzer after asking for at least something. George also committed to piano roll for Standard at one of his Saturday recording sessions, becoming only a moderate seller. But George Gershwin was now a song writer at only seventeen.

This meant that he would play new songs for potential customers, often producers or stage singers, in poorly insulated cubicles amidst a sea of other pianos. However, it did earn him some income, and it inspired George to write some as well. He also found some work arranging and playing piano rolls of ragtime and popular songs for Standard Music Rolls at Perfection Studios in East Orange, New Jersey. With another friend, Murray Roth, George composed When You Want 'Em, You Can't Get 'Em (When You've Got 'Em, You Don't Want 'Em), a clever ragtime tune with an unwieldy title. Gumble and others at Remick showed no interest, with Gumble having to admonish Gershwin, saying "You're here as a pianist, not a writer. We've got plenty of writers under contract." The pair ended up selling it to Harry Von Tilzer based on some urging by singer Sophie Tucker, with Roth accepting $15 up front, but George holding out for royalties. He eventually received a mere $5 from Von Tilzer after asking for at least something. George also committed to piano roll for Standard at one of his Saturday recording sessions, becoming only a moderate seller. But George Gershwin was now a song writer at only seventeen.

This meant that he would play new songs for potential customers, often producers or stage singers, in poorly insulated cubicles amidst a sea of other pianos. However, it did earn him some income, and it inspired George to write some as well. He also found some work arranging and playing piano rolls of ragtime and popular songs for Standard Music Rolls at Perfection Studios in East Orange, New Jersey. With another friend, Murray Roth, George composed When You Want 'Em, You Can't Get 'Em (When You've Got 'Em, You Don't Want 'Em), a clever ragtime tune with an unwieldy title. Gumble and others at Remick showed no interest, with Gumble having to admonish Gershwin, saying "You're here as a pianist, not a writer. We've got plenty of writers under contract." The pair ended up selling it to Harry Von Tilzer based on some urging by singer Sophie Tucker, with Roth accepting $15 up front, but George holding out for royalties. He eventually received a mere $5 from Von Tilzer after asking for at least something. George also committed to piano roll for Standard at one of his Saturday recording sessions, becoming only a moderate seller. But George Gershwin was now a song writer at only seventeen.In spite of the setbacks, Gershwin penned another tune with Roth, My Runaway Girl. It somehow caught the interest of composer Sigmund Romberg as it made the rounds, and was interpolated into the Passing Show of 1916, the first Gershwin tune to make it to the Broadway stage. As it turns out, Romberg had more interest in the composer and player than he did for the song, which more or less ended Roth's career, but started George's. Even better, Gershwin was employed as a rehearsal pianist for the show, and wrote the music for another tune, The Making of a Girl, with lyrics by Romberg and seasoned writer Harold Atteridge. He also made a step up in the piano roll business, working for Aeolian by late 1916. Over the next several years George would record over 100 piano rolls of popular tunes, including some of his own compositions. He was known to have worked under pseudonyms as well, including Fred Murtha and Bert Wynn.

Hoping to make his way as a composer of any genre, perhaps even improving on that genre or successfully merging popular forms with the classical ones he had been learning from Hambitzer and Kilenyi,  Gershwin teamed up with Will Donaldson, a somewhat older peer at Remick, for the rag Rialto Ripples. In reality, Donaldson may have applied his name to the piece, perhaps lightly arranging it, to give it more of a shot at publication. In fact, composer Felix Arndt, another mentor to George, may have had more influence on Rialto Ripples than anyone else. It was not immediately accepted, but by the time George got frustrated and either quit or was discharged from Remick in mid-March of 1917, it became the only Gershwin tune that the publisher took in. Ironically, Rialto Ripples was, in the short term, quite a sensation for Remick, but it was too late for them to capitalize on it and request more from George, who was now working as a rehearsal and performance pianist. One of the shows he worked for starting in July was Miss 1917 by Jerome Kern and Victor Herbert.

Gershwin teamed up with Will Donaldson, a somewhat older peer at Remick, for the rag Rialto Ripples. In reality, Donaldson may have applied his name to the piece, perhaps lightly arranging it, to give it more of a shot at publication. In fact, composer Felix Arndt, another mentor to George, may have had more influence on Rialto Ripples than anyone else. It was not immediately accepted, but by the time George got frustrated and either quit or was discharged from Remick in mid-March of 1917, it became the only Gershwin tune that the publisher took in. Ironically, Rialto Ripples was, in the short term, quite a sensation for Remick, but it was too late for them to capitalize on it and request more from George, who was now working as a rehearsal and performance pianist. One of the shows he worked for starting in July was Miss 1917 by Jerome Kern and Victor Herbert.

Gershwin teamed up with Will Donaldson, a somewhat older peer at Remick, for the rag Rialto Ripples. In reality, Donaldson may have applied his name to the piece, perhaps lightly arranging it, to give it more of a shot at publication. In fact, composer Felix Arndt, another mentor to George, may have had more influence on Rialto Ripples than anyone else. It was not immediately accepted, but by the time George got frustrated and either quit or was discharged from Remick in mid-March of 1917, it became the only Gershwin tune that the publisher took in. Ironically, Rialto Ripples was, in the short term, quite a sensation for Remick, but it was too late for them to capitalize on it and request more from George, who was now working as a rehearsal and performance pianist. One of the shows he worked for starting in July was Miss 1917 by Jerome Kern and Victor Herbert.

Gershwin teamed up with Will Donaldson, a somewhat older peer at Remick, for the rag Rialto Ripples. In reality, Donaldson may have applied his name to the piece, perhaps lightly arranging it, to give it more of a shot at publication. In fact, composer Felix Arndt, another mentor to George, may have had more influence on Rialto Ripples than anyone else. It was not immediately accepted, but by the time George got frustrated and either quit or was discharged from Remick in mid-March of 1917, it became the only Gershwin tune that the publisher took in. Ironically, Rialto Ripples was, in the short term, quite a sensation for Remick, but it was too late for them to capitalize on it and request more from George, who was now working as a rehearsal and performance pianist. One of the shows he worked for starting in July was Miss 1917 by Jerome Kern and Victor Herbert.By late 1917 George had worked out a few more tunes with another lyricist he met while making the rounds, Irving Caesar. Three years his senior, Irving already had some connections in the theater world which would soon pay off. But George found another writing partner as well, one Arthur Francis. They gave the partnership a try, and eventually found their stride, working together for the next 20 years. In truth, the name was a pseudonym from Ira Gershwin derived from the names of their younger siblings. It was supposedly to keep Ira's own identity and not capitalize on George's growing reputation, but in 1917 that was not fully realized yet. After Miss 1917 opened in November, George remained at the Century Theater as an organizer of and accompanist for a series of popular concerts they had each Sunday evening.  Through this gig word of his talents both as a pianist and composer spread, and very soon in early 1918 he was offered a regular position as a staff pianist and composer by Max Dreyfus, a manager at T.B. Harms Publishing Company. This included a fairly decent weekly salary in exchange for rights on any future compositions he would produce, a forward looking move on the part of Dreyfus.

Through this gig word of his talents both as a pianist and composer spread, and very soon in early 1918 he was offered a regular position as a staff pianist and composer by Max Dreyfus, a manager at T.B. Harms Publishing Company. This included a fairly decent weekly salary in exchange for rights on any future compositions he would produce, a forward looking move on the part of Dreyfus.

Through this gig word of his talents both as a pianist and composer spread, and very soon in early 1918 he was offered a regular position as a staff pianist and composer by Max Dreyfus, a manager at T.B. Harms Publishing Company. This included a fairly decent weekly salary in exchange for rights on any future compositions he would produce, a forward looking move on the part of Dreyfus.

Through this gig word of his talents both as a pianist and composer spread, and very soon in early 1918 he was offered a regular position as a staff pianist and composer by Max Dreyfus, a manager at T.B. Harms Publishing Company. This included a fairly decent weekly salary in exchange for rights on any future compositions he would produce, a forward looking move on the part of Dreyfus.On his 1918 draft record George is listed as an actor composer for the Nora Bayes Theatrical Company, and as being employed by the T.B. Harmes [sic] Publishing Company. For a short while he worked on the vaudeville stage as an accompanist for the more famous Bayes, as well as singer Louise Dresser. The listed address on the draft record is different than that of his parents. On Ira's draft record he is listed under the name Isidore, not as a lyricist however, but rather as an employee of his fathers at the St. Nicholas Bath. George lists his mother Rose as a reference and Ira lists his father Morris. There is a bittersweet irony in this as a few years later, around the time that George was receiving great acclaim for his symphonic works, Rose credited Ira for their overall success, a contention she held to the end of her life, and a frustration for the composing half of the Gershwin team. Indeed, one of their first songs written together, The Real American Folk Song is a Rag, was getting some notice in the music Ladies First, and There's Magic in the Air would find its way into Half Past Eight later in the year. But George was working with other lyricists as well, mostly in short term relationships. By the end of 1918 his songs would be in three Broadway shows. Still a fresh talent, even as a veteran at age 19, George Gershwin would not see his first real hit until the following year.

The Rise to Fame

From this point on nearly every song that came from Gershwin would either find its way into a Broadway show, or be specifically composed as part of one. (Note that this does not include his famous instrumental works.) In 1919 various Gershwin songs found their way into three Broadway musicals, and he would write the scores for two others. La, La, Lucille, a show composed with prolific lyricist Buddy G. DeSylva and associate Arthur J. Jackson, would be his first full-fledged assignment. It ran for 104 performances, not bad for a first attempt. He was also charged with Morris Gest's Midnight Whirl, a revue comprised of Gershwin music to lyrics by DeSylva and John Henry Mears. It ran for a less impressive 68 performances before closing. But in the interim, George and Irving Caesar had dashed off a little ragtime song, supposedly in a mere 15 minutes, that was interpolated into the unimpressive Capitol Revue. A three part song titled Swanee, it did not go far until Caesar asked an acquaintance to give it a try. That acquaintance heard Gershwin's dynamic performance of it at a party and decided to give it a new home. Thus it was that Swanee was interpolated into the decidedly non-Southern show Sinbad by singer Al Jolson who ran with it and never stopped. To think that Jolie made George famous, and that at some point Gershwin's fame would handily eclipse that of the bombastic stage star. It was further a hit in London when injected into Jig Saw, and within a year George , also establishing a fan base for the composer in England. By the end of 1920, both Irving and George would be overwhelmed by a reported $10,000 each in performance and sales royalties. As it turned out, this would be his biggest song hit during his lifetime, and one of his biggest breaks. It was also featured in the first audio recording with Gershwin at the piano, albeit with the trio of famed banjoist Fred Van Eps. Given the nature of acoustic recording, the banjo dominated this track so Gershwin is difficult to hear, but glimpses of his genius are still present.

In 1919 various Gershwin songs found their way into three Broadway musicals, and he would write the scores for two others. La, La, Lucille, a show composed with prolific lyricist Buddy G. DeSylva and associate Arthur J. Jackson, would be his first full-fledged assignment. It ran for 104 performances, not bad for a first attempt. He was also charged with Morris Gest's Midnight Whirl, a revue comprised of Gershwin music to lyrics by DeSylva and John Henry Mears. It ran for a less impressive 68 performances before closing. But in the interim, George and Irving Caesar had dashed off a little ragtime song, supposedly in a mere 15 minutes, that was interpolated into the unimpressive Capitol Revue. A three part song titled Swanee, it did not go far until Caesar asked an acquaintance to give it a try. That acquaintance heard Gershwin's dynamic performance of it at a party and decided to give it a new home. Thus it was that Swanee was interpolated into the decidedly non-Southern show Sinbad by singer Al Jolson who ran with it and never stopped. To think that Jolie made George famous, and that at some point Gershwin's fame would handily eclipse that of the bombastic stage star. It was further a hit in London when injected into Jig Saw, and within a year George , also establishing a fan base for the composer in England. By the end of 1920, both Irving and George would be overwhelmed by a reported $10,000 each in performance and sales royalties. As it turned out, this would be his biggest song hit during his lifetime, and one of his biggest breaks. It was also featured in the first audio recording with Gershwin at the piano, albeit with the trio of famed banjoist Fred Van Eps. Given the nature of acoustic recording, the banjo dominated this track so Gershwin is difficult to hear, but glimpses of his genius are still present.

In 1919 various Gershwin songs found their way into three Broadway musicals, and he would write the scores for two others. La, La, Lucille, a show composed with prolific lyricist Buddy G. DeSylva and associate Arthur J. Jackson, would be his first full-fledged assignment. It ran for 104 performances, not bad for a first attempt. He was also charged with Morris Gest's Midnight Whirl, a revue comprised of Gershwin music to lyrics by DeSylva and John Henry Mears. It ran for a less impressive 68 performances before closing. But in the interim, George and Irving Caesar had dashed off a little ragtime song, supposedly in a mere 15 minutes, that was interpolated into the unimpressive Capitol Revue. A three part song titled Swanee, it did not go far until Caesar asked an acquaintance to give it a try. That acquaintance heard Gershwin's dynamic performance of it at a party and decided to give it a new home. Thus it was that Swanee was interpolated into the decidedly non-Southern show Sinbad by singer Al Jolson who ran with it and never stopped. To think that Jolie made George famous, and that at some point Gershwin's fame would handily eclipse that of the bombastic stage star. It was further a hit in London when injected into Jig Saw, and within a year George , also establishing a fan base for the composer in England. By the end of 1920, both Irving and George would be overwhelmed by a reported $10,000 each in performance and sales royalties. As it turned out, this would be his biggest song hit during his lifetime, and one of his biggest breaks. It was also featured in the first audio recording with Gershwin at the piano, albeit with the trio of famed banjoist Fred Van Eps. Given the nature of acoustic recording, the banjo dominated this track so Gershwin is difficult to hear, but glimpses of his genius are still present.

In 1919 various Gershwin songs found their way into three Broadway musicals, and he would write the scores for two others. La, La, Lucille, a show composed with prolific lyricist Buddy G. DeSylva and associate Arthur J. Jackson, would be his first full-fledged assignment. It ran for 104 performances, not bad for a first attempt. He was also charged with Morris Gest's Midnight Whirl, a revue comprised of Gershwin music to lyrics by DeSylva and John Henry Mears. It ran for a less impressive 68 performances before closing. But in the interim, George and Irving Caesar had dashed off a little ragtime song, supposedly in a mere 15 minutes, that was interpolated into the unimpressive Capitol Revue. A three part song titled Swanee, it did not go far until Caesar asked an acquaintance to give it a try. That acquaintance heard Gershwin's dynamic performance of it at a party and decided to give it a new home. Thus it was that Swanee was interpolated into the decidedly non-Southern show Sinbad by singer Al Jolson who ran with it and never stopped. To think that Jolie made George famous, and that at some point Gershwin's fame would handily eclipse that of the bombastic stage star. It was further a hit in London when injected into Jig Saw, and within a year George , also establishing a fan base for the composer in England. By the end of 1920, both Irving and George would be overwhelmed by a reported $10,000 each in performance and sales royalties. As it turned out, this would be his biggest song hit during his lifetime, and one of his biggest breaks. It was also featured in the first audio recording with Gershwin at the piano, albeit with the trio of famed banjoist Fred Van Eps. Given the nature of acoustic recording, the banjo dominated this track so Gershwin is difficult to hear, but glimpses of his genius are still present.Fortunately for fans with reproducing pianos and for future preservation, Gershwin also recorded some reproducing rolls starting in 1919 for both the Welte-Mignon and Duo-Art formats. His most celebrated series of rolls were still a few years off, but these demonstrated his forward thinking as a pianist brought up on ragtime and popular song, and advancing it through complex rhythms and chord progressions. Where Swanee was a fine example of a contemporary tune, George was already looking to advancing his classical training into new forms of music that in some cases forecast what was to com. Having lost Hambitzer as an instructor, George soon moved on to classical Rubin Goldmark, and for an alternate point of view, composer and music theory teacher Henry Cowell, known for some rather avant garde material. Even in advance of Zez Confrey's series of novelties of the 1920s, in 1919 George managed his Novelette in Fourths, which actually has some kinship with Confrey's Kitten on the Keys and My Pet, pieces that would emerge within two years. In pursuit of advancing the classical form, he also composed Lullaby for a string quartet, part of his training with Kilenyi.

Even in advance of Zez Confrey's series of novelties of the 1920s, in 1919 George managed his Novelette in Fourths, which actually has some kinship with Confrey's Kitten on the Keys and My Pet, pieces that would emerge within two years. In pursuit of advancing the classical form, he also composed Lullaby for a string quartet, part of his training with Kilenyi.

Even in advance of Zez Confrey's series of novelties of the 1920s, in 1919 George managed his Novelette in Fourths, which actually has some kinship with Confrey's Kitten on the Keys and My Pet, pieces that would emerge within two years. In pursuit of advancing the classical form, he also composed Lullaby for a string quartet, part of his training with Kilenyi.

Even in advance of Zez Confrey's series of novelties of the 1920s, in 1919 George managed his Novelette in Fourths, which actually has some kinship with Confrey's Kitten on the Keys and My Pet, pieces that would emerge within two years. In pursuit of advancing the classical form, he also composed Lullaby for a string quartet, part of his training with Kilenyi.But in spite of his ambition to be the great American classical or jazz composer, Broadway was calling, literally. It was another George who would keep Gershwin busy for the next several years. George White hoped to compete with Florenz Ziegfeld by putting on his own revue, giving it the salacious and enticing title of George White's Scandals. The first edition was in 1920, running for 134 performances, featuring songs composed by Gershwin and Arthur Jackson. There were no big hits, but a lot of notice of this new force on the great white way. They would repeat the feat in 1921, with the memorable Drifting Along with the Tide outlasting most of the rest of the songs. Meanwhile in 1920, George had another nine tunes interpolated into four more musicals, which got him even more work in 1921. The 1920 Census showed that he was once again living with his parents, as was Ira. George was listed as a composer and Isadore as a lyric writer. Morris was in the restaurant business at that time.

With Caesar and DeSylva he tried to recreate the success of Swanee with Swanee Rose (a.k.a.) Dixie Rose, but nothing happened with it. Slightly discouraged but moving forward, he teamed up with a cadre of young composers for The Broadway Whirl, and had pieces interpolated into or commissioned for no less than six other musicals. Among those requesting Gershwin's services was lyricist and producer E. Ray Goetz, who had high regard for the composer, and would work with him on a number of shows. Goetz and DeSylva replaced Jackson as the lyricists for 1922 edition of George White's Scandals, which ran 89 performances and yielded I'll Build a Stairway to Paradise. Another ambitious effort from that show ran only the first night before it was dropped. Titled Blue Monday it was a miniature opera co-composed with DeSylva, running around 25 minutes, with a format and plot that bears some similarity to the later Slaughter on Tenth Avenue by Richard Rodgers. There may be a variety of reasons why it was dropped, such as slowing down the second act of the show, or perhaps being too cerebral for the time. It generally demonstrates Gershwin's ambitions to move beyond mere popular music, but also shows that he needed a little more fine tuning in the execution of this form. The Blue Monday Blues from the work remained in the show. Another DeSylva/Gershwin piece included in The French Doll, Do It Again, would become another Gershwin standard over the next few years. Gershwin was also tapped for Our Nell with another trio of lyricist composers, which fell flat at 40 performances and yielded nothing memorable.

It generally demonstrates Gershwin's ambitions to move beyond mere popular music, but also shows that he needed a little more fine tuning in the execution of this form. The Blue Monday Blues from the work remained in the show. Another DeSylva/Gershwin piece included in The French Doll, Do It Again, would become another Gershwin standard over the next few years. Gershwin was also tapped for Our Nell with another trio of lyricist composers, which fell flat at 40 performances and yielded nothing memorable.

It generally demonstrates Gershwin's ambitions to move beyond mere popular music, but also shows that he needed a little more fine tuning in the execution of this form. The Blue Monday Blues from the work remained in the show. Another DeSylva/Gershwin piece included in The French Doll, Do It Again, would become another Gershwin standard over the next few years. Gershwin was also tapped for Our Nell with another trio of lyricist composers, which fell flat at 40 performances and yielded nothing memorable.

It generally demonstrates Gershwin's ambitions to move beyond mere popular music, but also shows that he needed a little more fine tuning in the execution of this form. The Blue Monday Blues from the work remained in the show. Another DeSylva/Gershwin piece included in The French Doll, Do It Again, would become another Gershwin standard over the next few years. Gershwin was also tapped for Our Nell with another trio of lyricist composers, which fell flat at 40 performances and yielded nothing memorable.The year 1923 was only a bit slower for the young composer, who may have taken pause after a few misfires in order to recharge and turn out better material. Fulfilling his agreement with White, Gershwin and DeSylva, with some help from Goetz, created a score for George White's Scandals of 1923, which improved over the previous year for a total of 168 performances. He also made contributions to The Dancing Girl and Little Miss Bluebird, both relatively successful productions. Earlier in the year Gershwin had met British lyricist Clifford Grey who asked him to collaborate on a new work for the London stage. George ended up visiting London and Paris for a while, becoming known to many there while he finished work on The Rainbow. Not a raging success, it still established his presence in the United Kingdom. At the end of the year, George and Buddy finished off Sweet Little Devil which played in 1924. In the meantime, the sometimes overworked Gershwin may have forgotten a meeting with one of his admirers, bandleader Paul Whiteman, who was impressed with much of what he had heard of Gershwin, particularly at a November 1, 1923 recital at Aeolian Hall where he performed with Canadian mezzo-soprano Eva Gauthier which featured some of his songs and those by contemporaries Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern and Walter Donaldson. Whiteman was planning on a concert in the same venue for early 1924 that would feature some of the best available jazz music of that time in a formal setting, and asked George if he might contribute a symphonic work of some kind to be featured in the program. The understanding was that George agreed to do so, but it may have been a handshake commitment because it was evidently forgotten.

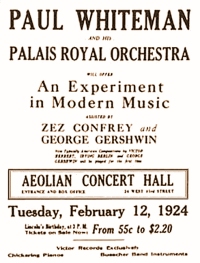

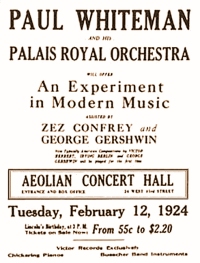

The Rhapsody and The Reaction

Just after the New Year started in 1924, Ira pointed out a blurb in a New York newspaper to George, claiming he had agreed to write a Jazz Concerto for Whiteman's orchestra. With just five weeks left before the concert, it was clear to Ira that George hadn't even started on it yet, and given that the piece was already generating buzz in the press it became paramount that work get underway.  The next day George was on his way to Boston and heard the rhythm of the train wheels, inspiring him towards at least one of the melodies in the concerto. Soon after this he improvised a placid and lush melody while playing at a party, and realized it was the main theme he had hoped for. So Gershwin quickly dashed off a two-piano score for the concerto, leaving some of the pages for his part of the piece blank. Whiteman handed it off to composer and arranger Ferdé Grofé, who turned it into a score for the Whiteman orchestra.

The next day George was on his way to Boston and heard the rhythm of the train wheels, inspiring him towards at least one of the melodies in the concerto. Soon after this he improvised a placid and lush melody while playing at a party, and realized it was the main theme he had hoped for. So Gershwin quickly dashed off a two-piano score for the concerto, leaving some of the pages for his part of the piece blank. Whiteman handed it off to composer and arranger Ferdé Grofé, who turned it into a score for the Whiteman orchestra.

The next day George was on his way to Boston and heard the rhythm of the train wheels, inspiring him towards at least one of the melodies in the concerto. Soon after this he improvised a placid and lush melody while playing at a party, and realized it was the main theme he had hoped for. So Gershwin quickly dashed off a two-piano score for the concerto, leaving some of the pages for his part of the piece blank. Whiteman handed it off to composer and arranger Ferdé Grofé, who turned it into a score for the Whiteman orchestra.

The next day George was on his way to Boston and heard the rhythm of the train wheels, inspiring him towards at least one of the melodies in the concerto. Soon after this he improvised a placid and lush melody while playing at a party, and realized it was the main theme he had hoped for. So Gershwin quickly dashed off a two-piano score for the concerto, leaving some of the pages for his part of the piece blank. Whiteman handed it off to composer and arranger Ferdé Grofé, who turned it into a score for the Whiteman orchestra.Thus it was that on February 12th, in a concert titled An Experiment in Modern Music, that featured works by Victor Herbert, Edward Elgar and Zez Confrey, a less than confident Gershwin took his seat at the piano near the end of the concert. The clarinet started on what would become a famous slide up to a high Bb, and the first performance of Rhapsody in Blue was underway. Gershwin himself ended up improvising in some sections of the score that he had not yet filled in, but the orchestra managed to stay in synch with him. At one point, by his own account, he started crying he was so moved by the experience - or perhaps intimidated - and came to his senses several pages later, not knowing how he had conducted that far. The final chords brought a standing ovation and noisy acclaim from an audience that included violinists Fritz Kreisler and Jascha Heifitz, conductor Leopold Stokowski, and composers Serge Rachmaninov and Igor Stravinsky. This was the moment that set in stone George Gershwin's place in American and world music history and development, and redefined him as a musician as well as composer. The critics weren't sure how to categorize the piece in their reviews, either as classical or jazz, or even a hybrid. But they could not ignore that it was popular with the general public, as well as with his peers.

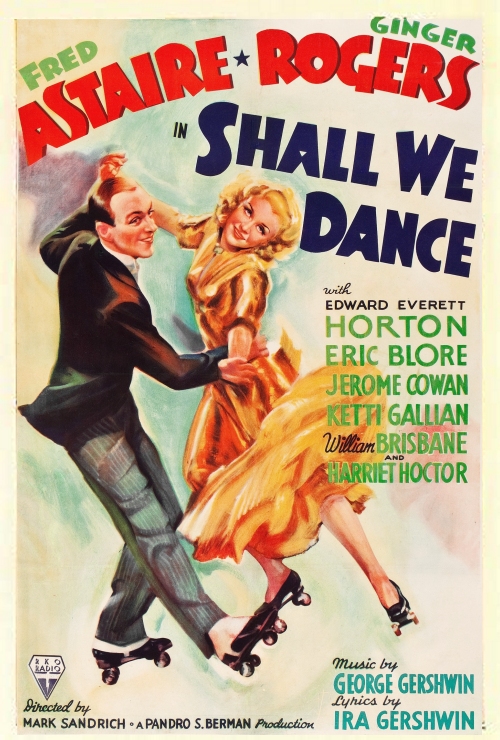

That was just the beginning of 1924. Soon after the concert Gershwin recorded an abridged version of the work with Whiteman's orchestra on an acoustic recording. He also embarked on his most ambitious Broadway shows to date. With DeSylva and Goetz, the trio wrote the annual score for George White's Scandals, lasting 196 performances. It would the last Scandals he would be directly involved in. Following that, George turned to Ira, with whom he had already composed several songs, for a purely Gershwin show. Lady Be Good was immensely successful, playing for 330 performances in its original run. Among the memorable tunes were the title song, Oh, Lady Be Good, and Fascinatin' Rhythm. The show opened in December and featured the brother/sister dance team of Fred and Adele Astaire, who had also been making a splash in London around that time. It also served as some evidence that perhaps Ira was the best possible fit as a lyricist for George's music. Even before Lady Be Good, the brothers had also co-composed the score for Primrose with British lyricist Desmond Carter, a show which like The Rainbow was produced exclusively for the London stage, and not performed in the United States until sixty-three years after its British debut.

Broadway, Carnegie Hall, London and Paris

At some point in 1925, now flush with money and fame, George was able to move uptown to the upper West Side of Manhattan, providing a much more fashionable and comfortable home for his parents there as well. He also put his money to use engaging more in art, attempting to paint to a degree (Ira turned out to be a fairly accomplished oil canvas artist),  and collecting a number of pieces of art as well. Being that Gershwin was in vogue, he was frequently invited to parties given within the theatrical or literary circles of New York, and was implored to play at virtually all of them. It has been said that sometimes it was a little hard to push George towards the piano, but once there he dominated the evening with his repertoire and repartee. George was also traveling a bit more in 1925, overseeing productions in England as well as visits to Paris. Among those that he developed a close social relationship with was Fred Astaire, with whom George would remain friends to the end of his life.

and collecting a number of pieces of art as well. Being that Gershwin was in vogue, he was frequently invited to parties given within the theatrical or literary circles of New York, and was implored to play at virtually all of them. It has been said that sometimes it was a little hard to push George towards the piano, but once there he dominated the evening with his repertoire and repartee. George was also traveling a bit more in 1925, overseeing productions in England as well as visits to Paris. Among those that he developed a close social relationship with was Fred Astaire, with whom George would remain friends to the end of his life.

and collecting a number of pieces of art as well. Being that Gershwin was in vogue, he was frequently invited to parties given within the theatrical or literary circles of New York, and was implored to play at virtually all of them. It has been said that sometimes it was a little hard to push George towards the piano, but once there he dominated the evening with his repertoire and repartee. George was also traveling a bit more in 1925, overseeing productions in England as well as visits to Paris. Among those that he developed a close social relationship with was Fred Astaire, with whom George would remain friends to the end of his life.

and collecting a number of pieces of art as well. Being that Gershwin was in vogue, he was frequently invited to parties given within the theatrical or literary circles of New York, and was implored to play at virtually all of them. It has been said that sometimes it was a little hard to push George towards the piano, but once there he dominated the evening with his repertoire and repartee. George was also traveling a bit more in 1925, overseeing productions in England as well as visits to Paris. Among those that he developed a close social relationship with was Fred Astaire, with whom George would remain friends to the end of his life.While Gershwin had recorded countless rolls from the late 1910s on, most of them to date had been standard non-expression piano rolls with a few reproducing rolls done along the way. Duo-Art managed to get him exclusively in 1925, as announced in the February 7 edition of The Music Trade Review: "George Gershwin, the young American composer who leaped into sudden fame with his jazz-classic, the 'Rhapsody in Blue,' has recorded that composition for the Duo-Art. Gershwin has been known on Broadway for several years as a writer of popular song hits, and as a pianist of much ability. It was but a year ago, however, that his 'Rhapsody in Blue,' first performed by Paul Whiteman's Orchestra in Aeolian Hall, stamped him as something more than a jazz composer. He is now hailed as the one composer capable of translating the true spirit of American jazz into classic composition. In future he will record exclusively for the Duo-Art... The 'Rhapsody' is written for augmented jazz orchestra with solo piano. For the Duo-Art Gershwin has recorded his own arrangement of the work for piano alone, a clever combination of the brilliant and difficult solo part and the rich orchestration. The composition will be published in two rolls." Indeed, it required two passes at the very least to create the arranged rolls of the large-scope work. In recent times, many fine recordings of Rhapsody in Blue with Gershwin at the piano have been achieved by using edited versions of this fine roll set.

The first musical of that year was Tell Me More co-written with Ira and Bud DeSylva. It fared moderately well on Broadway at 100 performances, but was also taken to London with three additional tunes composed with Desmond Carter, and did a little better there.  Tip-Toes was next, lasting for an admirable 192 performances over half the year. Among the great tunes that came from it were Looking for a Boy, That Certain Feeling and Sweet and Low Down. With the unusual combination of Herbert Stothart, Otto Harbach and Oscar Hammerstein Jr., Gershwin stepped a bit closer to classic theater with Song of the Flame. Even though it lasted into 1926 at 219 performances, he would not team with them again.

Tip-Toes was next, lasting for an admirable 192 performances over half the year. Among the great tunes that came from it were Looking for a Boy, That Certain Feeling and Sweet and Low Down. With the unusual combination of Herbert Stothart, Otto Harbach and Oscar Hammerstein Jr., Gershwin stepped a bit closer to classic theater with Song of the Flame. Even though it lasted into 1926 at 219 performances, he would not team with them again.

Tip-Toes was next, lasting for an admirable 192 performances over half the year. Among the great tunes that came from it were Looking for a Boy, That Certain Feeling and Sweet and Low Down. With the unusual combination of Herbert Stothart, Otto Harbach and Oscar Hammerstein Jr., Gershwin stepped a bit closer to classic theater with Song of the Flame. Even though it lasted into 1926 at 219 performances, he would not team with them again.

Tip-Toes was next, lasting for an admirable 192 performances over half the year. Among the great tunes that came from it were Looking for a Boy, That Certain Feeling and Sweet and Low Down. With the unusual combination of Herbert Stothart, Otto Harbach and Oscar Hammerstein Jr., Gershwin stepped a bit closer to classic theater with Song of the Flame. Even though it lasted into 1926 at 219 performances, he would not team with them again.George also had a lot on his plate, having been commissioned to write another symphonic work by conductor Walter Damrosch and the New York Symphony Orchestra, who had attended the premiere of Rhapsody in Blue. He spent most of the summer and early fall of 1925 focusing on the work. Still lacking some of the necessary theory and orchestration skills he needed, Gershwin hit the books to become self-taught in these to a degree. The experience also prompted to later seek out training from Wallingford Riegger and Henry Cowell to help fill out his musical knowledge base. Originally titled New York Concerto, it emerged in November as Concerto in F. Unlike Rhapsody in Blue, this was a full-fledged three section concerto, and it was orchestrated completely by Gershwin with a little advice from Damrosch dispensed during early run-throughs. Premiering at Carnegie Hall on December 3rd, it was well attended and well received by most. Stravinsky was there once again and thought the difficult work to be brilliant. Sergei Prokofiev had no use for it, making it clear that he did not like Gershwin's work at all. Some thought it to be too classical in the same vein as French impressionist Claude Debussy, and not more closely associated with American jazz. Just the same, it further cemented George's reputation as a contemporary American classicist at age 27, a worthy accomplishment. A lasting impression has been left by this piece, with one of the most ambitious and eclectic performances by Gershwin's admirer and slightly younger peer Oscar Levant, who performed the third movement (with himself shown on screen as all of the members of the orchestra) in the all-Gershwin MGM film An American in Paris.

One happy event in Gershwin's life was an ongoing relationship with composer Kay Swift, who had met in 1925. This made Swift's husband Jimmy Warburg rather unhappy, but he tolerated it for a time trying to compete with Gershwin for her attention. In the end, their marriage collapsed. Kay was involved with Gershwin nearly to the end of his life. One rather blatant show of affection on George's part was naming his next show, Oh, Kay!, for her. With lyrics by Ira it opened in 1926 and turned out to be a very inspired and romantic turn for the brothers, running an impressive 256 performances, and yielding the lasting hit Someone to Watch Over Me. Surprisingly, in its original form that song was not the slow ballad we know today, but more of lilting swinging tune, performed on piano roll by George the same year in that manner. He would also contribute a couple of pieces to the London production of Lady Be Good, including the memorable I'd Rather Charleston.

While in London, George met again up with Fred and Adele Astaire. Taking advantage of the advanced electronic recording technology in studios there, the trio recorded some tracks together. They represent some of the finest audio recordings of Gershwin's playing, as well as some of Fred's dancing. Yet George still pursued his desire to compose classically infused jazz pieces, still somewhat influenced by the French impressionists.  Now taking some instruction in advanced composition, he penned a set of preludes that year, and by some reports was planning a series of etudes as well. Even though there may have been as many as six composed, George performed his Three Preludes for Piano in December of 1926 as part of a recital where he also accompanied contralto Marguerite d'Alvarez. Historians have further extrapolated that the unpublished pieces found in the archives titled Sleepless Nights and Novelette (restructured as Short Story may have also been intended as part of the prelude set.

Now taking some instruction in advanced composition, he penned a set of preludes that year, and by some reports was planning a series of etudes as well. Even though there may have been as many as six composed, George performed his Three Preludes for Piano in December of 1926 as part of a recital where he also accompanied contralto Marguerite d'Alvarez. Historians have further extrapolated that the unpublished pieces found in the archives titled Sleepless Nights and Novelette (restructured as Short Story may have also been intended as part of the prelude set.

Now taking some instruction in advanced composition, he penned a set of preludes that year, and by some reports was planning a series of etudes as well. Even though there may have been as many as six composed, George performed his Three Preludes for Piano in December of 1926 as part of a recital where he also accompanied contralto Marguerite d'Alvarez. Historians have further extrapolated that the unpublished pieces found in the archives titled Sleepless Nights and Novelette (restructured as Short Story may have also been intended as part of the prelude set.

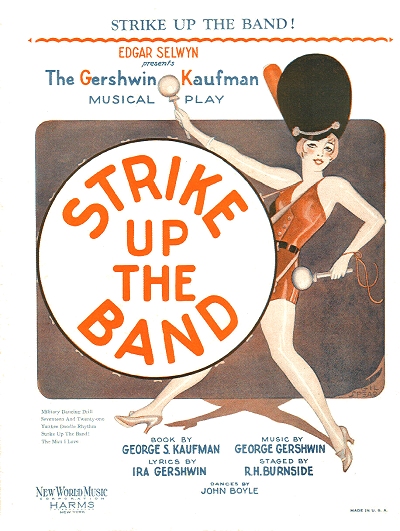

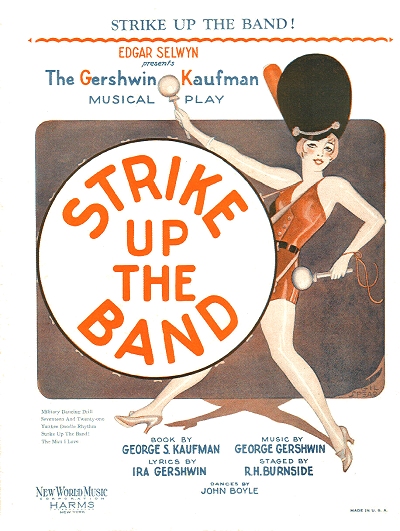

Now taking some instruction in advanced composition, he penned a set of preludes that year, and by some reports was planning a series of etudes as well. Even though there may have been as many as six composed, George performed his Three Preludes for Piano in December of 1926 as part of a recital where he also accompanied contralto Marguerite d'Alvarez. Historians have further extrapolated that the unpublished pieces found in the archives titled Sleepless Nights and Novelette (restructured as Short Story may have also been intended as part of the prelude set.The next Gershwin musical would leave a sour taste in the mouth of many, including the Gershwin brothers. Teaming up with playwright George S. Kaufman, who had recently scored with the Marx Brothers' musicals The Cocoanuts (with Irving Berlin), he teamed with the Gershwins to write and produce the political satire Strike up the Band in early 1927. In spite of a fine score in which Ira took Kaufman's libretto and turned it into workable lyrics, the show did not make it to Broadway, closing in Philadelphia after only a few performances. While this somewhat expensive proposition was not too much of a burden for the brothers, the loss to them musically after the effort put into it was disheartening. One of the pieces included had already been dropped from a show in 1924. The Man I Love ended up being dropped once again, as was the entire show soon after. However, it has become one of the most enduring ballads composed in the 20th century, and sold very well on its own once it was heard on recordings. The show was simply set aside and they moved on to other projects. Among those was Funny Face, which at 244 performances was far from a disappointment for the brothers. Among the memorable pieces from that production was the enduring 'S Wonderful and the clever The Babbitt and the Bromide.

While George had recorded Rhapsody in Blue with the Whiteman orchestra in 1924, it was an acoustic recording of only moderate quality. So in 1927 he joined the orchestra again for another take at an abbreviated version of the piece recorded electronically by Victor. However, even with the composer present and at the piano, Paul Whiteman had some issues with how the piece was to be interpreted and ended up leaving the session. In order to get a take while the musicians were still present, Nathan Shilkret, a staff conductor who was on hand that day, took over to finish the recording. In spite of this, Whiteman would still long be associated with the piece in two different guises. The original orchestration by Grofé was for jazz band, but a later orchestration had many string elements added, making the piece more symphonic in presentation. This later version would be included in the 1930 Whiteman movie, King of Jazz, with the piano in that interpretation played by the very capable novelty pianist Roy Bargy. While Gershwin did not perform in the film, he still performed at the premiere of the picture on May 2, 1930. Whiteman was not the only who capitalized on the work. It was incorporated into George White's Scandals of 1926 even though Gershwin was no longer composing for the leader, in Americana also in 1926, the musical Lucky in 1927, and George White's Musical Hall Varieties of 1932). It would eventually be utilized in a number of other movies as well, the most iconic being Woody Allen's Manhattan, and one of the finest renditions featured in the Disney Studio's Fantasia 2000, both of which starred New York City as their logical background, and even as the star. So it was that even by the late 1920s Rhapsody in Blue was deeply associated with Gershwin, New York, and Whiteman.

The following year was quite eventful for the Gershwins as well. The brothers debuted two ambitious musicals that year - one a hit and one a near-miss. Rosalie was first, including some input from Sigmund Romberg and writer P.G. Wodehouse.  While it did not yield any lasting hits, it ran for nearly a year at 335 performances, a worthy run even in those pre-Depression times. They followed this up with Treasure Girl, which lasted for a mere 68 performances before the final curtain. One nice piece came out of this, albeit as more of a jaunty dance tune than the ballad most are familiar with today. (I've Got a) Crush on You rose above the rest, and has been frequently recorded over the decades since. But after all this writing for Broadway, George needed a break, and had a desire to explore more of the fusion of jazz and classical forms, hoping to fuse them into something that would eclipse even his Rhapsody in Blue

While it did not yield any lasting hits, it ran for nearly a year at 335 performances, a worthy run even in those pre-Depression times. They followed this up with Treasure Girl, which lasted for a mere 68 performances before the final curtain. One nice piece came out of this, albeit as more of a jaunty dance tune than the ballad most are familiar with today. (I've Got a) Crush on You rose above the rest, and has been frequently recorded over the decades since. But after all this writing for Broadway, George needed a break, and had a desire to explore more of the fusion of jazz and classical forms, hoping to fuse them into something that would eclipse even his Rhapsody in Blue

While it did not yield any lasting hits, it ran for nearly a year at 335 performances, a worthy run even in those pre-Depression times. They followed this up with Treasure Girl, which lasted for a mere 68 performances before the final curtain. One nice piece came out of this, albeit as more of a jaunty dance tune than the ballad most are familiar with today. (I've Got a) Crush on You rose above the rest, and has been frequently recorded over the decades since. But after all this writing for Broadway, George needed a break, and had a desire to explore more of the fusion of jazz and classical forms, hoping to fuse them into something that would eclipse even his Rhapsody in Blue