Considered by many to be one of the "big three" of boogie woogie players of the late 1930s into the 1940s, Pete Johnson was actually, in some ways, the odd man out, but perhaps the most versatile of that group, which included Meade "Lux" Lewis and Albert Ammons. He actually joined forces with them more than a decade after they had been working together with their own careers, and was instrumental in helping them climb to the top for a short burst of time just before World War II. But his beginnings were quite a bit different from his Chicago compatriots. While there are still some missing elements in his story, the best possible effort has been made here to get facts pinned down and provide a relatively stable timeline for the first three decades of Pete's life.

He was born in or near Kansas City, Missouri, as Kermit Holden, although it is unclear how long that last name would stay with him. His father was Nathan Anderson Holden, a saloon porter, and his mother Lucille Johnson, both Missouri natives. It was said he was actually born in a room above the saloon at 19th and Holmes in Kansas City. Although Kermit was difficult to find in the 1910 Federal census, the 1904 year of birth is widely accepted as being accurate, despite some of his peers born around the same time having trimmed years off their age even in their teens. The 1910 census also revealed that Nathan Holden had just been remarried, having left Bertha and Kermit when the boy was around three years old. While the March 25 date has been widely accepted, his Social Security death record shows it as March 24, so even that has a bit of a question mark on it. Lucille, already impoverished even before her husband abandoned her, chose to send Kermit to an orphanage when he was three,

according to some sources, although he may have been slightly older. The conditions there were not much better, and he quickly became ill and homesick. Kermit longed for his mother and his home such as it was, and ran away on one or more occasions, eventually ending up with Bertha again. She abandoned the orphanage idea and somehow managed to raise him as best she could in their one room lodging either in or near McClure Flats, one of the poorest areas of Kansas City. His early bed was said to be a dresser drawer.

|

Kermit had already been given his mother's last name of Johnson by the early 1910s (evidently retaining Holden for a middle name). Around 1916, having filled out as a twelve-year-old who could pass for sixteen, Pete quit school and went to work in order to help his mother out. This included shining shoes, working in a china packing plant, as a theater usher, in a slaughterhouse, and as an apprentice or gopher in a print shop. By the time of the 1920 enumeration he was shown still living with his mother and working as a porter in a barber shop. Lucille had managed to raise their standard of living in a better location at 85 Garfield Avenue north of downtown, and helped to keep a roof over their heads by running her home as a boarding house, with seven lodgers shown as residing there in January of 1920.

For his initial foray into music, Kermit showed in interest in marching bands, sometimes getting lost while following them through the streets. In his early teens took up playing drums. He took lessons from drummer Charles T. Watts and gained enough skill that he was able to play for pay with bands around Kansas City for some four years. However, the piano also had some allure for him, particularly since there was no work involved in setting up and breaking down for gigs as there was with a drum kit. During a stint working as a water boy for a construction firm rebuilding a church, Kermit had access to building's piano on which he started to experiment after work. He took this new-found passion out into the world, trying to play in area bars, but more often to derision rather than applause, being ridiculed to the point of humiliation. One incident was recounted in The Pete Johnson Story in Jazz Report Magazine of April 1962:

…there was a card playing place on 18th in Kansas City which had an old beat-up piano. The manager used to let Pete practice there. Apparently, this one time, it got on the nerves of one card player. He asked Pete, "Do you know 'The Silent Rag'? Pete was eager to learn, and asked him how it went. "First you take your foot off the pedal." That seemed reasonable. "Then you take your hands off the keys." Well, what kind of rag is this? "Then you take your ass off the seat and get out of here!" Everyone roared with laughter; not Pete, he felt about so big.

After stepping back from the instrument for a time, he was instructed in piano by Louis "Bootie" Johnson. The lessons may have been for free, as Louis was looking for somebody to fill in for him at his playing gigs when he was unable to fulfill the contract having been on an alcoholic bender. It was enough to whet Kermit's interest again, and this time he stuck with it.

Another one of his mentors was his uncle, Charles "Smash" Johnson, who gave him more even-handed and in depth instruction in piano, allowing him to learn how to play ragtime and popular music properly. Other influences he cited were Myrtle Hawkins, "Slam Foot" Brown, Udall Wilson and Stacey LaGuardia. The latter played in a club at the storied corner of 12th and Vine in Kansas City. Johnson also took in some theory from Buster Smith, followed by Bill Steven, who was a keen improvisor known by other musicians as "The Harmony King."

|

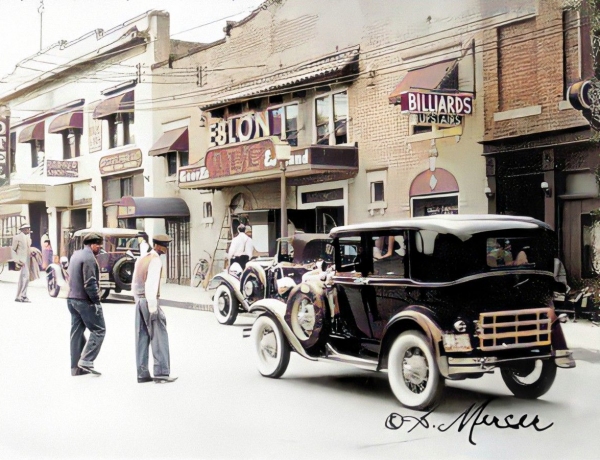

Even though he was listed as Kermit in the 1920 enumeration, at some point during this instruction, while he was also starting to earn a living, Kermit took on the name "Pete," and continued to use it for the remainder of his life, although apparently never as a legal name change. With his developing skills he found work playing at rent parties and some more formal events in his late teens and into his twenties. Accompanying him to many of these events as a drummer was his friend "Mud" Johnson. After sitting in for a few other pianists, Pete secured a gig at the Backbiter's Club, a speakeasy in north Kansas City in the section known as Little Italy. Other locations that followed including the Grey Goose, the Spinning Wheel, the Yellow Front Club, and the Peacock Inn, working for low wages but good tips, depending on the crowd. Many of these low-paying gigs, most often at $3 per night, involved hours stretching into dawn, and the players either accepted the conditions or were not employed. Unlike many other cities like Detroit, Chicago and New York, union representation for musicians was weak or nonexistent in Kansas City, which allowed the exploitation by club owners. While Pete was working at the Hawaiian Gardens in the late 1920s, the speakeasy was raided by the J. Edgar Hoover's squad for prohibition violations. He was given the option to take the piano from the club, but could not afford to. He was also asked to appear in court and identify the owners of the place, but the owners were a bit more "persuasive" in insisting that he just stay home, which he did.

Pete had not only learned enough popular styles to be relevant throughout the 1920s, working in both cabarets and speakeasys, but gained skills as an accompanist and as a band member, also necessary for maintaining even a paltry working wage for a musician in his position. He also absorbed what he could by other pianists through their recordings. In the late 1920s, one of his favorites was Thomas "Fats" Waller, who had been born in the same year, but had managed to record for Victor Records as early as 1922. He quickly picked up stride piano style from listening to the records by Waller and some of his peers. Once records were made available by Chicago boogie woogie player Clarence "Pine Top" Smith in 1929, released posthumously owing to his tragic death from a stray bullet early in the year, Pete quickly took up that style. He would soon make it his own, applying an even more aggressive approach as the 1930s approached.

Pete quickly took up that style. He would soon make it his own, applying an even more aggressive approach as the 1930s approached.

Pete quickly took up that style. He would soon make it his own, applying an even more aggressive approach as the 1930s approached.

Pete quickly took up that style. He would soon make it his own, applying an even more aggressive approach as the 1930s approached.In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Pete was often found working with traveling orchestras when not in Kansas City clubs. One of those was the Rockette Swing Unit fronted by Pete's early school mate Herman Walder on alto saxophone. The 1930 census showed him lodging in a St. Joseph, Missouri, home, likely that of drummer Abie Price. It also indicated that he had been married and now divorced, although to whom was difficult to ascertain. However, he would soon form his own small group around 1932. One of the members was Joe Turner, who was a few years younger than Pete, but was quickly becoming a talented vocalist. Turner was underage when he started to sneak into the Backbiter's Club, using a fake drawn-on moustache and fedora pulled down low on his head. He longed to be on stage and made several requests of Pete to sit in and sing a few songs. Pete finally gave in, and their long association was started. When Pete moved his group to the Black and Tan Club, Turner would work part time as a bartender, coming up on stage to take a few vocals before returning to his duties. By the 1933, Pete and his group were working for "Piney" Brown who managed the Sunset Crystal Palace. He was more sympathetic to working musicians than the exploitative club owners, and was highly regarded by Pete and Joe who later dedicated the Piney Brown Blues to him. Another amiable employer was Ellis Burton, who generously made sure his musicians had enough food to eat and some kind of lodging if it was needed.

Another amiable employer was Ellis Burton, who generously made sure his musicians had enough food to eat and some kind of lodging if it was needed.

Another amiable employer was Ellis Burton, who generously made sure his musicians had enough food to eat and some kind of lodging if it was needed.

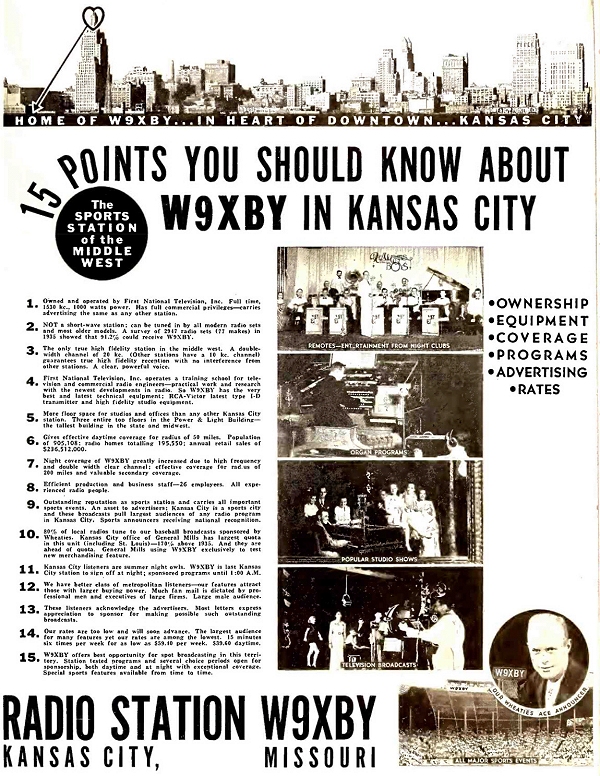

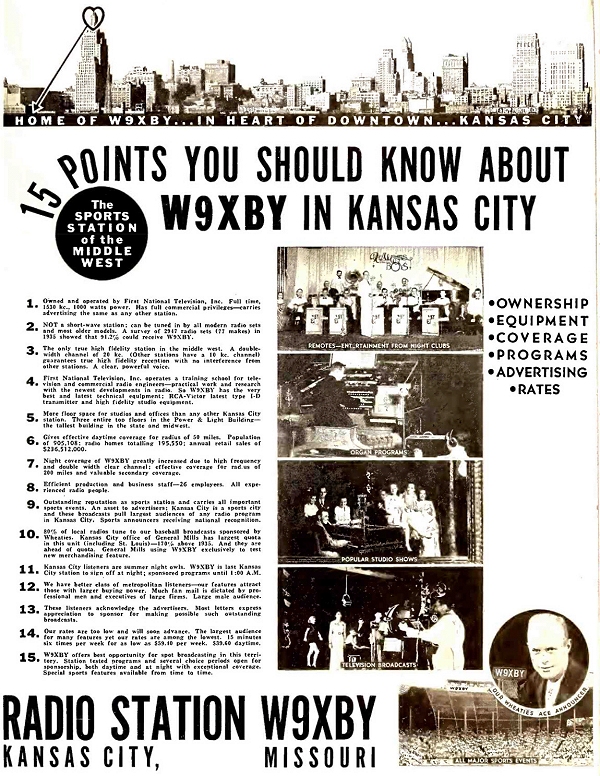

Another amiable employer was Ellis Burton, who generously made sure his musicians had enough food to eat and some kind of lodging if it was needed.Johnson and Turner's band not only played for dances and shows, but they were offered the opportunity to broadcast over experimental high-fidelity station W9XBY in the early afternoon hours and occasional evenings starting in 1935 into 1936. The station, which also had some early television broadcasts, was above the usual AM band frequency with a wider bandwidth than standard stations, which also gave it a relatively long range from Kansas City, reaching at times from Los Angeles to New York and even parts of Canada. This gave national exposure, depending on the time of broadcast, to several Kansas City groups, primarily the black musicians. (When the experiment was scuttled in 1941 by the FCC, the station became KITE at 1590 AM.) It was in 1936 that New York music entrepreneur John Hammond, who was in Chicago at that time, heard a W9XBY broadcast of the Count Basie Orchestra that clued him in to the music scene in that city. (Some reports also credit Benny Goodman with turning Hammond on this music scene.) This led him not only to Basie, but to Johnson and Turner, and a few other Kansas City musicians. Visiting them with agent Willard Alexander at his side, Hammond invited the duo and their band to play at the Famous Door on 52nd Street in New York City, and the Apollo Theatre in nearby Harlem. It is possible that the musical style they brought with them was too foreign for East Coast ears, or because they decided to go more mainstream with a ballad rather than their usual boogie woogie and blues. The group was ultimately not well-received, returning home after only two performances. But that was hardly the end of the story. In the interim, Pete was married to Margaret Johnson (evidently her maiden name as per the certificate) on May 24, 1938. Their daughter, also named Margaret (Lucille), had been born some months prior to the official wedding.

Whether it was Hammond, Goodman or Alexander, after Count Basie and his orchestra scored a big success in New York in January, 1938 at both Carnegie Hall and in Harlem, and with the "discovery" of Chicago boogie woogie musicians Albert Ammons, Meade "Lux" Lewis and others by Hammond around the same time as he found Johnson, Alexander extended another offer to the group to return to New York and play for Benny Goodman's radio show sponsored by Camel cigarettes. They accepted, and playing more in their accustomed style, scored well with audiences. This led to the now famous grouping of Johnson with Ammons and Lewis by Hammond for the December 23, 1938, concert From Spirituals to Swing, also held at Carnegie Hall. Almost immediately after their historic appearance in the storied venue, playing six-handed boogie woogie on two pianos to vocals by Joe Turner, a whole new fascination with the genre exploded into the world and cultivated the boogie woogie craze of the early 1940s.

Alexander extended another offer to the group to return to New York and play for Benny Goodman's radio show sponsored by Camel cigarettes. They accepted, and playing more in their accustomed style, scored well with audiences. This led to the now famous grouping of Johnson with Ammons and Lewis by Hammond for the December 23, 1938, concert From Spirituals to Swing, also held at Carnegie Hall. Almost immediately after their historic appearance in the storied venue, playing six-handed boogie woogie on two pianos to vocals by Joe Turner, a whole new fascination with the genre exploded into the world and cultivated the boogie woogie craze of the early 1940s.

Alexander extended another offer to the group to return to New York and play for Benny Goodman's radio show sponsored by Camel cigarettes. They accepted, and playing more in their accustomed style, scored well with audiences. This led to the now famous grouping of Johnson with Ammons and Lewis by Hammond for the December 23, 1938, concert From Spirituals to Swing, also held at Carnegie Hall. Almost immediately after their historic appearance in the storied venue, playing six-handed boogie woogie on two pianos to vocals by Joe Turner, a whole new fascination with the genre exploded into the world and cultivated the boogie woogie craze of the early 1940s.

Alexander extended another offer to the group to return to New York and play for Benny Goodman's radio show sponsored by Camel cigarettes. They accepted, and playing more in their accustomed style, scored well with audiences. This led to the now famous grouping of Johnson with Ammons and Lewis by Hammond for the December 23, 1938, concert From Spirituals to Swing, also held at Carnegie Hall. Almost immediately after their historic appearance in the storied venue, playing six-handed boogie woogie on two pianos to vocals by Joe Turner, a whole new fascination with the genre exploded into the world and cultivated the boogie woogie craze of the early 1940s.Shortly after the concert, Alan Lomax, who had recently completed the now-famous cycle of recordings by Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton on his life and music, interviewed the trio of Johnson, Ammons and Lewis for the Library of Congress, along with some recordings of their playing. All three of them were further tapped for new records, including the double-sided Boogie Woogie Prayer released on the OKeh and Vocalion labels (and later on Columbia). Both Albert and Meade had already been recorded prior to this date, so it was ostensibly Pete's first time in a commercial recording studio, along with Turner. One of their first cuts for Vocalion yielded Roll 'Em Pete, which is considered by many music historians as a template for rhythm and blues, and ultimately rock and roll, which would fully develop around eight and sixteen years off in the future respectively.

Separately, Johnson, Ammons and Lewis were also the first artists to record tracks for the newly minted Solo Art label. For Blue Note, a label formed by European enthusiast and performer Alfred Lion on the heels of that Carnegie Hall appearance, Pete recorded six sides, most of them hard-hitting Kansas City style boogie woogie and blues.

|

Pete was then invited again to play at the Famous Door, but when asked to come down to Café Society, a Greenwich Village nightclub in lower Manhattan where Ammons and Lewis had been engaged along with Turner, in order to give Albert some hints on how he accompanied Joe's vocals, Hammond immediately realized that Pete would be a great addition to that venue instead. So it was that the three boogie woogie pianists found themselves featured at the Café Society, working as the Boogie Woogie Trio, sometimes billed as the Boogie Woogie Boys when Turner was singing. They collectively ended up playing there regularly for at least two years, and their performances were occasionally broadcast on the air from the club. They would occasionally take time off from New York to play at the Sherman Hotel in Chicago. In both cities they were joined by prominent jazz musicians of the day, both black and white. During this period of 1939 into 1941, Pete managed to snag several recording dates, both as a soloist and with various groups, including his own ensemble and that of trumpeter Oran "Hot Lips" Page. He and his cohorts were also featured on a number of radio broadcasts from Chicago, including shortwave shows on CBS intended for the United Kingdom. The 1940 census showed Johnson residing in Manhattan with Margaret and their like-named daughter, working as a musician in a night club.

The 1940 census showed Johnson residing in Manhattan with Margaret and their like-named daughter, working as a musician in a night club.

The 1940 census showed Johnson residing in Manhattan with Margaret and their like-named daughter, working as a musician in a night club.

The 1940 census showed Johnson residing in Manhattan with Margaret and their like-named daughter, working as a musician in a night club.The group broke up at some point in 1941 due to a variety of factors. Lewis, who appears to have been tired of sharing the spotlight with the dynamic powerhouse Johnson, made his way to Los Angeles where he would stay for the remainder of his life, commuting at times to Chicago for gigs. Turner went back to Kansas City, although he would record several more times with Pete. Albert continued to play with Pete for a while longer, including a set of eight sides for Victor in May of 1941. However, at some point late in the year Ammons reportedly sliced off part of a fingertip with a kitchen knife. Albert suffered complications from the injury, as well as some potential mini-strokes, which resulted in the loss of use of his hands for a time due to pain and paralysis. He managed to recover within a couple of years, playing once again with Pete in Chicago and Saint Louis. By early 1944, the craze for boogie woogie, and even swing music, was dying down for a public that was already looking forward to a life beyond the war which would soon come to an end. Fortunately, some of Pete's performance style, along with Albert's, was captured by the camera in the short film Boogie Woogie Dream, which featured singer Lena Horne and the orchestra of pianist Teddy Wilson. However, Albert decided to go back on the road, leaving Pete as a soloist once again.

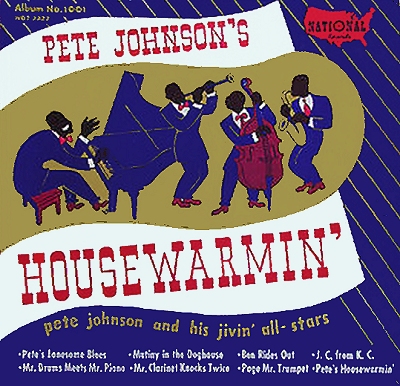

In February of 1944, with the war heading toward a crescendo in Europe, Pete went into the Decca studio to record eight solo sides that transcended his prior work, even his relentless Death Ray Boogie from 1941. These cuts showed a growing nuance and range that set him apart from many of his peers. Four more sides were cut with Turner late in the year. Then, from early 1945 to late 1946, Johnson appears to have recorded exclusively for the National Record Company, at least under his own name. He may have accompanied other artists on other labels or on the radio outside of his four National sessions, but this appeared to be his label of choice during that time. The four February 1945 sides were as part of the Hot Lips Page Band with Turner providing his characteristic vocals. The three 1946 sessions were with a similar group of musicians, but this time as Pete Johnson's All Stars. Among the memorable standouts was the driving Atomic Boogie, probably a reference to the dropping of the two atomic bombs the prior August, and a long point of controversy.

These cuts showed a growing nuance and range that set him apart from many of his peers. Four more sides were cut with Turner late in the year. Then, from early 1945 to late 1946, Johnson appears to have recorded exclusively for the National Record Company, at least under his own name. He may have accompanied other artists on other labels or on the radio outside of his four National sessions, but this appeared to be his label of choice during that time. The four February 1945 sides were as part of the Hot Lips Page Band with Turner providing his characteristic vocals. The three 1946 sessions were with a similar group of musicians, but this time as Pete Johnson's All Stars. Among the memorable standouts was the driving Atomic Boogie, probably a reference to the dropping of the two atomic bombs the prior August, and a long point of controversy.

These cuts showed a growing nuance and range that set him apart from many of his peers. Four more sides were cut with Turner late in the year. Then, from early 1945 to late 1946, Johnson appears to have recorded exclusively for the National Record Company, at least under his own name. He may have accompanied other artists on other labels or on the radio outside of his four National sessions, but this appeared to be his label of choice during that time. The four February 1945 sides were as part of the Hot Lips Page Band with Turner providing his characteristic vocals. The three 1946 sessions were with a similar group of musicians, but this time as Pete Johnson's All Stars. Among the memorable standouts was the driving Atomic Boogie, probably a reference to the dropping of the two atomic bombs the prior August, and a long point of controversy.

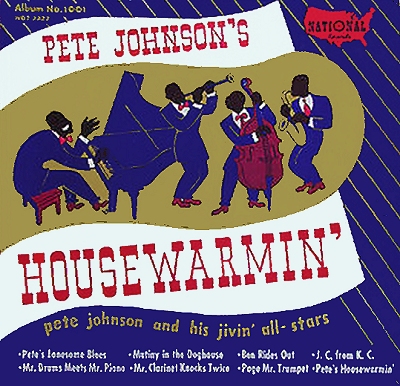

These cuts showed a growing nuance and range that set him apart from many of his peers. Four more sides were cut with Turner late in the year. Then, from early 1945 to late 1946, Johnson appears to have recorded exclusively for the National Record Company, at least under his own name. He may have accompanied other artists on other labels or on the radio outside of his four National sessions, but this appeared to be his label of choice during that time. The four February 1945 sides were as part of the Hot Lips Page Band with Turner providing his characteristic vocals. The three 1946 sessions were with a similar group of musicians, but this time as Pete Johnson's All Stars. Among the memorable standouts was the driving Atomic Boogie, probably a reference to the dropping of the two atomic bombs the prior August, and a long point of controversy.Eight of the January 26, 1946, sessions became part of an early informal concept record album, Pete Johnson's Housewarmin' on the National label, their first album release. Starting on the first disc, Pete is heard playing solo, allegedly in a new empty house (that needs rent money to sustain). Then several soloists from Kansas City bands in particular join him. Among them are J. C. Heard on drums, along with a bass and guitar, J. C. Higginbotham on trombone, Albert Nicholas on clarinet, Ben Webster on tenor saxophone, and his old friend Page on the trumpet. Each of them has a solo side backed by Johnson, and then for the last discs entire group jams together. The effect is very much like how rent parties of the 1920s and 1930s probably sounded, as exemplified in the Fats Waller tune, This Joint is Jumpin, and highlights the talent that was cultivated in his home town. This album, released on LP and CD as House Rent Party by the Savoy label, is still available in its entirety on CD and digital download.

The effect is very much like how rent parties of the 1920s and 1930s probably sounded, as exemplified in the Fats Waller tune, This Joint is Jumpin, and highlights the talent that was cultivated in his home town. This album, released on LP and CD as House Rent Party by the Savoy label, is still available in its entirety on CD and digital download.

The effect is very much like how rent parties of the 1920s and 1930s probably sounded, as exemplified in the Fats Waller tune, This Joint is Jumpin, and highlights the talent that was cultivated in his home town. This album, released on LP and CD as House Rent Party by the Savoy label, is still available in its entirety on CD and digital download.

The effect is very much like how rent parties of the 1920s and 1930s probably sounded, as exemplified in the Fats Waller tune, This Joint is Jumpin, and highlights the talent that was cultivated in his home town. This album, released on LP and CD as House Rent Party by the Savoy label, is still available in its entirety on CD and digital download.In 1947, and 1948 into 1949, Pete, who was now apparently single again, ventured to California to test out the waters there. Hooking up once again in 1947 with Albert, who was at least partially active once again, they performed at a Hollywood Club, The Streets of Paris. Joe, who was also enjoying California, joined him for a while both in Los Angeles and San Francisco. Johnson also did solo work, including a stint at the Hotel Ambassador in Santa Monica and an appearance in a jazz concert at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles. A performance of Pete and numerous other artists staged in Pasadena in mid-1947 was produced and committed to disc by Gene Norman and eventually released on LP by Vogue Records.

Pete also made several lesser-known recordings in late 1947 as the 1948 American Federation of Musicians (AFM) strike against recording studios loomed, keeping the studios particularly busy in November and December just before the deadline. Among those tracks, most done on the new magnetic tape format, were his Sunset Romp and Johnson's Boogie, which were also released in alternate overdubbed versions. They collectively helped to influence the rise of rhythm and blues that was already becoming popular. It appears that he also did some recording in June of 1948 during the strike with black entrepreneur Jack Lauderdale's recently formed Down Beat/Swing Time records, probably a non-union shop. There were also some cuts on Capitol backing vocalist Crown Prince Waterford that were arguably laid down the prior December, but may have been recorded for radio broadcast (a strike workaround) in early-to-mid 1948 as well. A few tracks for MGM with Turner and some on the Modern label rounded out the year. In early 1949 Pete recorded two takes of his Rocket Boogie "88" for (and by, according to the Swing Time label) Lauderdale, the 88 actually designating the number of keys on the piano, commonly used on that label, rather than the Oldsmobile "Rocket 88" introduced a year later. This track would later inspire singer Ike Turner to record his song Rocket 88, which was a reference to the car, and is considered by some historians to be the first true "Rock and Roll" song.

They collectively helped to influence the rise of rhythm and blues that was already becoming popular. It appears that he also did some recording in June of 1948 during the strike with black entrepreneur Jack Lauderdale's recently formed Down Beat/Swing Time records, probably a non-union shop. There were also some cuts on Capitol backing vocalist Crown Prince Waterford that were arguably laid down the prior December, but may have been recorded for radio broadcast (a strike workaround) in early-to-mid 1948 as well. A few tracks for MGM with Turner and some on the Modern label rounded out the year. In early 1949 Pete recorded two takes of his Rocket Boogie "88" for (and by, according to the Swing Time label) Lauderdale, the 88 actually designating the number of keys on the piano, commonly used on that label, rather than the Oldsmobile "Rocket 88" introduced a year later. This track would later inspire singer Ike Turner to record his song Rocket 88, which was a reference to the car, and is considered by some historians to be the first true "Rock and Roll" song.

They collectively helped to influence the rise of rhythm and blues that was already becoming popular. It appears that he also did some recording in June of 1948 during the strike with black entrepreneur Jack Lauderdale's recently formed Down Beat/Swing Time records, probably a non-union shop. There were also some cuts on Capitol backing vocalist Crown Prince Waterford that were arguably laid down the prior December, but may have been recorded for radio broadcast (a strike workaround) in early-to-mid 1948 as well. A few tracks for MGM with Turner and some on the Modern label rounded out the year. In early 1949 Pete recorded two takes of his Rocket Boogie "88" for (and by, according to the Swing Time label) Lauderdale, the 88 actually designating the number of keys on the piano, commonly used on that label, rather than the Oldsmobile "Rocket 88" introduced a year later. This track would later inspire singer Ike Turner to record his song Rocket 88, which was a reference to the car, and is considered by some historians to be the first true "Rock and Roll" song.

They collectively helped to influence the rise of rhythm and blues that was already becoming popular. It appears that he also did some recording in June of 1948 during the strike with black entrepreneur Jack Lauderdale's recently formed Down Beat/Swing Time records, probably a non-union shop. There were also some cuts on Capitol backing vocalist Crown Prince Waterford that were arguably laid down the prior December, but may have been recorded for radio broadcast (a strike workaround) in early-to-mid 1948 as well. A few tracks for MGM with Turner and some on the Modern label rounded out the year. In early 1949 Pete recorded two takes of his Rocket Boogie "88" for (and by, according to the Swing Time label) Lauderdale, the 88 actually designating the number of keys on the piano, commonly used on that label, rather than the Oldsmobile "Rocket 88" introduced a year later. This track would later inspire singer Ike Turner to record his song Rocket 88, which was a reference to the car, and is considered by some historians to be the first true "Rock and Roll" song.However, his luck during this period in the eastern half of the country was not so good, perhaps due to a poor booking agent. Another factor was that while he had diversified into virtually all forms of modern music, he was still billed as a boogie woogie pianist, and like the swing music of the prior decade, this was a fad that had lost favor with the general public. It did not help that most of his records of this period had "boogie" in the title. So, Johnson was often stranded in one or another location after gig, not having a permanent home to go to, and needing to cover his basic expenses. Most of the stops were between Detroit, Michigan, and parts of New England. Among the locations he played was a unique bar on the American side of Niagara Falls where the piano was situated above the bar, requiring Pete to climb a ladder in order to perform.

Among the locations he played was a unique bar on the American side of Niagara Falls where the piano was situated above the bar, requiring Pete to climb a ladder in order to perform.

Among the locations he played was a unique bar on the American side of Niagara Falls where the piano was situated above the bar, requiring Pete to climb a ladder in order to perform.

Among the locations he played was a unique bar on the American side of Niagara Falls where the piano was situated above the bar, requiring Pete to climb a ladder in order to perform.It was during this period in 1949 that Pete met and married his second wife, a competent pianist who was coincidentally named Margery, often short for Margaret, the name of both his first wife and daughter. Margery also played some boogie woogie piano, and would perform it and other styles at several New York recitals over the next few years. Given his apparent distaste for the West Coast, the geographical scope of his Midwest and Eastern gigs, and the need to have a home base with his wife, Pete chose to establish himself in Buffalo, New York around 1950. This allegedly put Pete in a good location to seek out work, but it was quickly apparent that such work would be hard to come by in Buffalo itself. In order to pay for lodging, Johnson had to take on manual labor, including a supermarket where as a receiving clerk he was responsible for driving trucks, as well as hanging and carrying meat, all for a reported $40 per week. The refrigerated environment helped to contribute to both arthritis and a bout with pneumonia, both maladies hampering his ability to play piano. Very few clubs in the area engaged him for any appreciable length of time, and he often had to work out of area, including as far away as Newport, Rhode Island; Detroit, Michigan; Binghamton, New York; and New York City.

There was a brief respite from worries in 1952 when Pete was teamed up with Meade Lux Lewis, Erroll Garner and Art Tatum as part of the Piano Parade. They toured from as far as Kansas City up into Canada, then back down to New York City where they ended with two weeks at Birdland on 52nd Street. He also did a Café Society concert at Carnegie Hall with Tatum, Albert Ammons, Lena Horne, John Kirby, Eddie South and Henry Red Allen, all for the Benefit of the Musician's Union Medical Fund. After a return to Buffalo, Pete did another stint with Meade in Detroit, then in August, Pete played for a few weeks in Kansas City before returning to his market job and two nights a week at Niagara Falls. While there, vocalist Crown Prince Waterford joined him for a bit in the fall. A new difficulty arose when after attending a concert to hear his hometown counterpart Count Basie play in Buffalo, his car got stuck in the snow. While trying to extract it he lost the tip of his left-hand little finger in a towrope, which sidelined him from any serious piano playing for the next several months, although he somehow managed with some heavy bandage cover.

A new difficulty arose when after attending a concert to hear his hometown counterpart Count Basie play in Buffalo, his car got stuck in the snow. While trying to extract it he lost the tip of his left-hand little finger in a towrope, which sidelined him from any serious piano playing for the next several months, although he somehow managed with some heavy bandage cover.

A new difficulty arose when after attending a concert to hear his hometown counterpart Count Basie play in Buffalo, his car got stuck in the snow. While trying to extract it he lost the tip of his left-hand little finger in a towrope, which sidelined him from any serious piano playing for the next several months, although he somehow managed with some heavy bandage cover.

A new difficulty arose when after attending a concert to hear his hometown counterpart Count Basie play in Buffalo, his car got stuck in the snow. While trying to extract it he lost the tip of his left-hand little finger in a towrope, which sidelined him from any serious piano playing for the next several months, although he somehow managed with some heavy bandage cover.In 1953 Pete toured less, mostly working for an ice cream company driving and washing trucks, while playing with small groups on the weekends as he recovered from his injury. He also worked several dives in Buffalo and Niagara, but as even the worst of these places liked to circulate through their already poorly paid musical acts, there was no steady employment. This spilled into the following year when he worked as a porter for a mortuary, again washing vehicles, and being dismissed on funeral days (race was still an issue in the mid-1950s, so a black man lingering near a white person's funeral may have seemed unsettling). All this was for around $25 per week, not exactly a living wage. However, in July of 1954 he was contracted for six weeks in Saint Louis, Missouri, where he not only played nightly, but for some radio broadcasts on Saturday at the Chase as well each weekend during his residency. During this time, on July 30 and August 1, at two house parties arranged by jazz entrepreneur John Phillips, Johnson and a couple of his peers were recorded performing some duets and trios. More importantly, he was able to stretch his stylistic muscles and play from his more contemporary repertoire, demonstrating his versatility and overall skill.

Then he returned to Buffalo, and worked for two apparently different venues that were both named The Ebony Room, one in Niagara Falls and one near his home. There was little work outside of Buffalo for him in from that time into 1955, but he did venture to the Berkshire Music Barn in Lenox, Massachusetts, for three different performances, including one with Joe Turner. He made scant recordings during this period, most of them private with no real distribution until after his death. There is very little known about his activities in 1956 or 1957, but they likely involved more menial day work along with weekends playing in unappreciative dives with few high points. His overall health also started to deteriorate with the lack of activity.

He made scant recordings during this period, most of them private with no real distribution until after his death. There is very little known about his activities in 1956 or 1957, but they likely involved more menial day work along with weekends playing in unappreciative dives with few high points. His overall health also started to deteriorate with the lack of activity.

He made scant recordings during this period, most of them private with no real distribution until after his death. There is very little known about his activities in 1956 or 1957, but they likely involved more menial day work along with weekends playing in unappreciative dives with few high points. His overall health also started to deteriorate with the lack of activity.

He made scant recordings during this period, most of them private with no real distribution until after his death. There is very little known about his activities in 1956 or 1957, but they likely involved more menial day work along with weekends playing in unappreciative dives with few high points. His overall health also started to deteriorate with the lack of activity.Then, in 1958, Pete was put back into the spotlight. Entrepreneur Norman Granz endeavored to include the now historic figure in his Jazz at the Philharmonic series. This entailed a European tour through many major cities, and also involved his old friend Joe Turner, along with more recent jazz figures such as Dizzy Gillispie and Stan Getz. Most of the shows were in front of capacity crowds in large venues. According to Marge, "They played Brussels, Amsterdam, Milan, Rome, Zurich, Munich, Frankfort, Hamburg, Berlin, Copenhagen, Oslo, Stockholm, Gothenburg and Paris." Some musicians suggested to Johnson that he consider remaining in France, due to their long love affair with jazz and plenty of club dates to go around. But not knowing the lay of the land and given his recent disappointments, the possibility of this not panning out as expected kept him from considering this possibility. Even as he was already on his way to the tour, an offer came in for Pete to appear at the 1958 Newport, Rhode Island, jazz festival. Accepting while still in Europe, Pete traveled to Newport shortly after returning to the US, and in addition to solo work accompanied Turner, rhythm and blues singers Ray Charles and Big Maybelle (Mabel Louis Smith), and rock and roller Chuck Berry. Also present for that legendary weekend were the Dave Brubeck Quartet, Duke Ellington Orchestra, Benny Goodman Orchestra, George Shearing Quintet, Billy Taylor Trio, Louis Armstrong, and Harlem stride pianist Willie "The Lion" Smith, so Pete was mingling with jazz royalty. There is a possibility that Pete was requested as a last-minute replacement for pianist Ray Bryant by Turner, as his name was not listed in the official program.

Pete returned to Buffalo, and after having not fell well for pretty much of the time during his recent travels, he decided to get a medical opinion. The diagnosis was that he had heart issues and the onset of diabetes. Not soon after this, he suffered a series of strokes of varying degrees, which created motor coordination issues in his hands, and almost disabling his previously powerful left hand. The proceeds from the trip could only sustain him for so long, and he and Marge struggled over the next four years to make ends meet. Poor eyesight compounded his condition even more.

Not soon after this, he suffered a series of strokes of varying degrees, which created motor coordination issues in his hands, and almost disabling his previously powerful left hand. The proceeds from the trip could only sustain him for so long, and he and Marge struggled over the next four years to make ends meet. Poor eyesight compounded his condition even more.

Not soon after this, he suffered a series of strokes of varying degrees, which created motor coordination issues in his hands, and almost disabling his previously powerful left hand. The proceeds from the trip could only sustain him for so long, and he and Marge struggled over the next four years to make ends meet. Poor eyesight compounded his condition even more.

Not soon after this, he suffered a series of strokes of varying degrees, which created motor coordination issues in his hands, and almost disabling his previously powerful left hand. The proceeds from the trip could only sustain him for so long, and he and Marge struggled over the next four years to make ends meet. Poor eyesight compounded his condition even more.Then around 1962, Jazz Report magazine published a series of articles written by Pete's wife Margery, more or less constituting a biography. Many readers and musicians who remembered Pete took up his cause and raised money through auctions, donations, and even musician's union leverage, to help him cover medical and living expenses. Hans Mauerer of Germany, a distant friend of many years, wrote a more extensive biography, The Pete Johnson Story, which was published in 1964, and from which the proceeds were sent directly to the Johnsons. Another helpful boost was Pete's acceptance to ASCAP in June, which assured him some income from publications and use of his work, including recordings. This was in part due to an article in Blues Unlimited that called out some of the record companies that had been stingy in allowing him royalties from continued sales of his work, now mostly compiled on LPs.

The end of 1964 into early 1965 was spent in the hospital to facilitate the operation and recovery on one of Pete's legs due to complications from the diabetes. Recovering from this and the strokes, he was able to perform nominally, mostly with his right hand. After having done this at a few smaller gatherings, Pete was invited to what constituted his eighth appearance at the 1967 Spirituals to Swing concert, still held at Carnegie Hall, the event that he had appeared at when the series was launched. While there, emcee Goddard Lieberson helped him onto the stage where he was reunited with Joe Turner for a brief moment. Turner dedicated a performance of Roll 'Em Pete to his long-time partner. Then as he was exiting the stage, Pete seated himself next to pianist Ray Bryant, and proceeded to play the treble line of the piece while Bryant handled the lower half of the piano. Johnson improved to a high level of confidence as the piece progressed, and was eventually rewarded with vibrant applause.

Two months later, in late March of 1967, shortly after having suffered another stroke, Kermit "Pete" Johnson died at Meyer Hospital in Buffalo, just two days before his 63rd birthday. He was laid to rest at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo with a very simple grave marker. It would still be many years before he was recognized for much beyond his role in the boogie woogie piano craze of the late 1930s, but as more compilations of his recorded body of work, including private issues, became available, Pete got his due and more. He is now remembered as perhaps the most versatile and dynamic of the cadre of black boogie woogie pianists that found their way into the ears of white society in the 1930s and 1940s, helping to slow sway opinions on their music, and enhancing the unique American songbook along the way. And that was perhaps helped to answer their boogie woogie prayer.

There were a number of disparate sources used to compile this article, including multiple discographies and overall disc listings, public and government records, several newspaper articles and periodicals, and a couple of books. Among the more useful sources which are highly recommended were the biographical article by Marge Johnson on her husband published in Jazz Report Magazine in the April, May and June 1962 issues, and The Story of Boogie Woogie by Peter J. Silvester in 2009.

Selected Discography

Selected Discography