Shelton Leroy Brooks (May 4, 1886 to September 6, 1975) | |

Compositions Compositions | |

|

1909

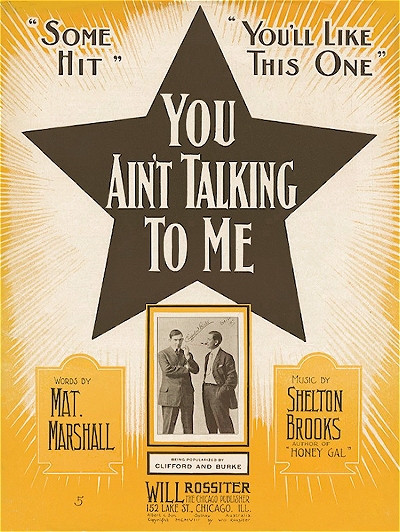

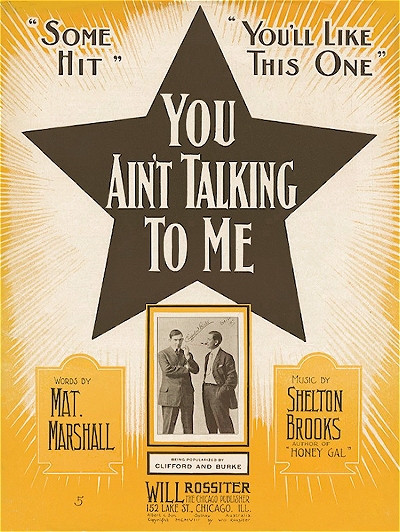

Honey GalYou Ain't Talking to Me [1] 1910

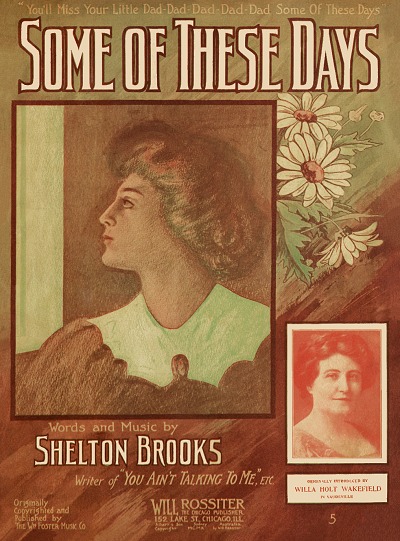

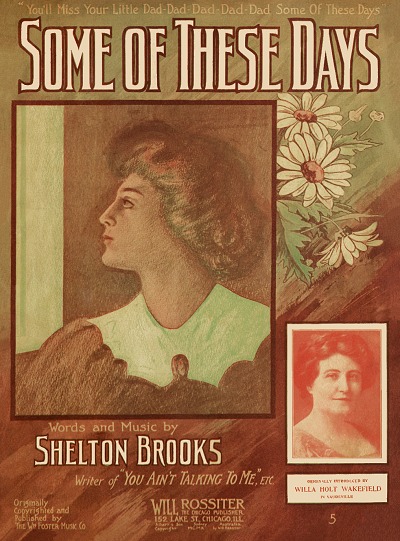

Some of These DaysYou Go In Mister Friend of Mine, I'll Stay Out Here Rufe Johnson's Harmony Band [2] 1911

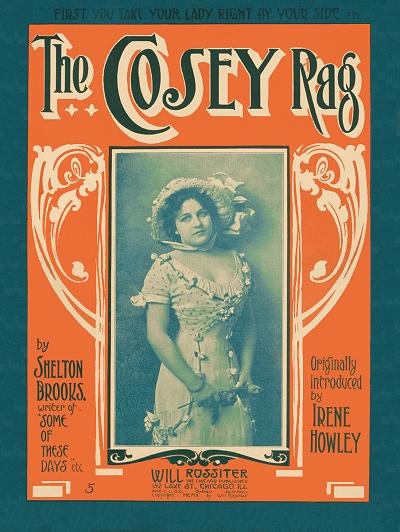

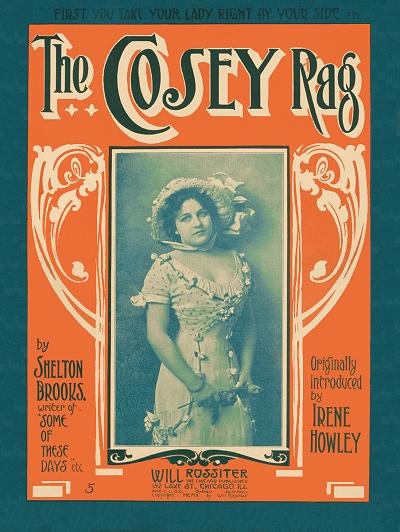

The Cosey RagThere'll Come a Time When You'll Feel Lonely That Humming Tune Just for You, Babe [3] It's Awf'ly Hard to Say Good-Bye to Someone You Love 1912

All Night LongA Beautiful Man You Ain't No Place But Down South [3] Oh! You Georgia Rose [4] 1913

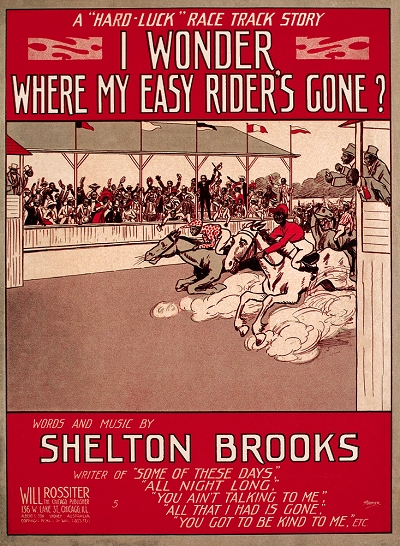

I Wonder Where My Easy Rider's GoneI Want to Do the Bearcat Dance At an Old-Time Ball 1914

Lonesome for YouYo' Got to Be Kind to Me I Cert'ny Wish He Would Come Back Give Me One More Chance Down on the Levee Ruff Johnson's Harmony Band [2] All That I Had is Gone [4] 1915

Kentucky RoseI'm Sorry the Day I Laid My Eyes on You You Can't Mend a Broken Heart If I Were a Bee and You Were a Red, Red Rose Since You Turned Me Down Since You Went Away [5] 1916

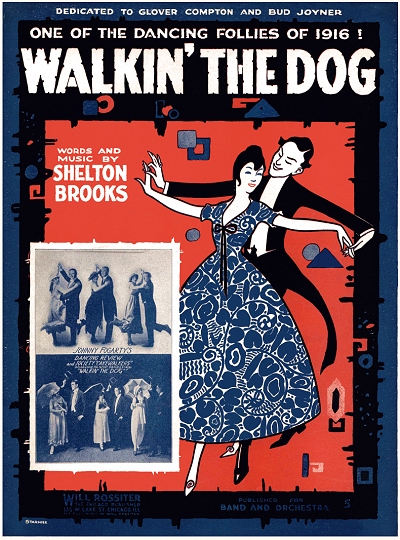

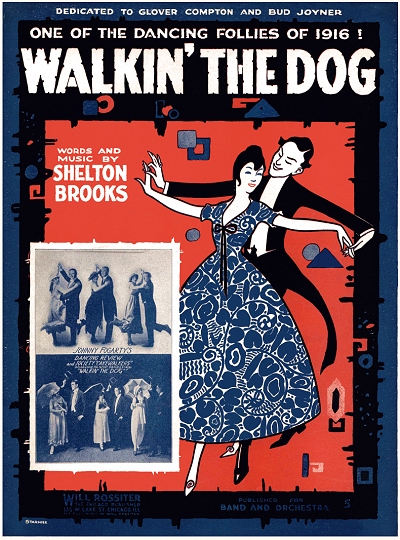

Walkin' the Dog1917

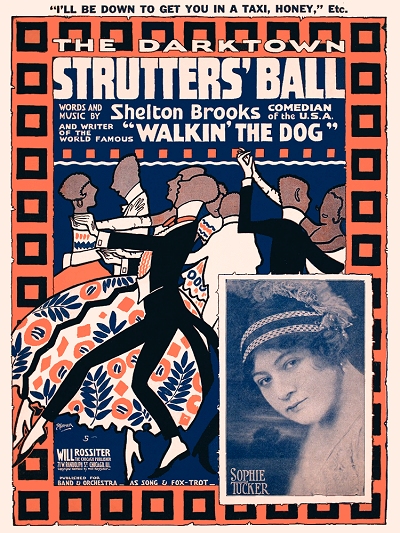

The Darktown Strutters' BallWhy Did You Make Me Love You? - Then Break My Heart Somewhere, Somewhere in France [6] That's What I Call Spreading Joy [7] The Faithful Rose [8] This Time Tomorrowm, Honey, You'll Be Mine [8] I Want My Wedding March Played in Jazz Time [8] 1918

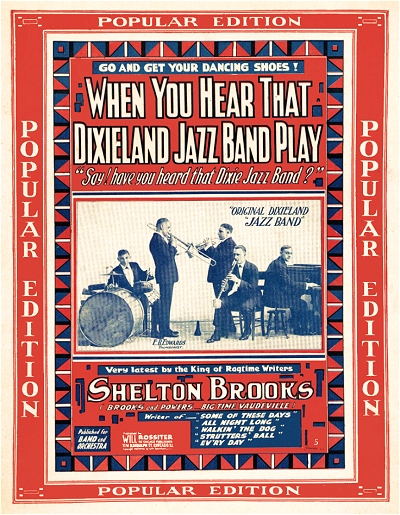

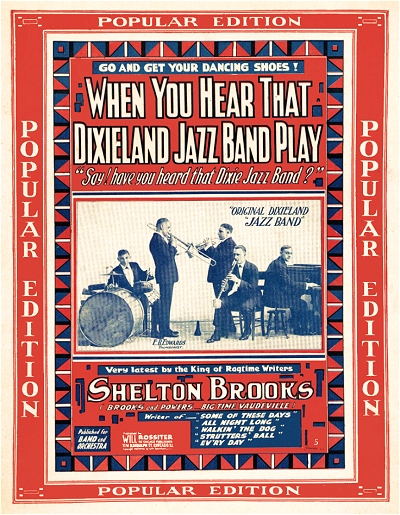

When You Hear That Dixie Jazz Band PlayLove-sick Blues At the Cotton Picker's Jubilee (I Want You) Ev'ry Day [4] After All These Years [9] 1919

JeanTell Me Why You Want to Go to Paree (You Can Get the Same Sweet Loving Here at Home) When the War is Over I'll Return to You [10] I Want to Shimmie [11] Wake Me Up Cooin' the Blues [12] Stop That Band [13] 1920

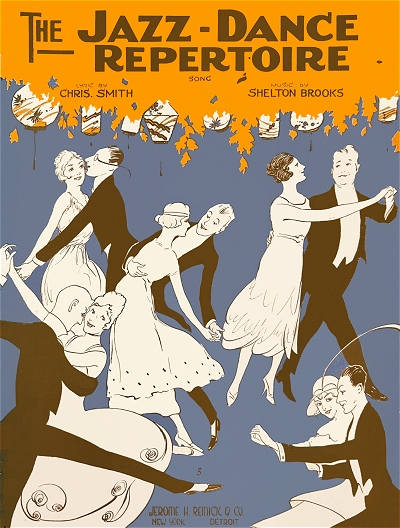

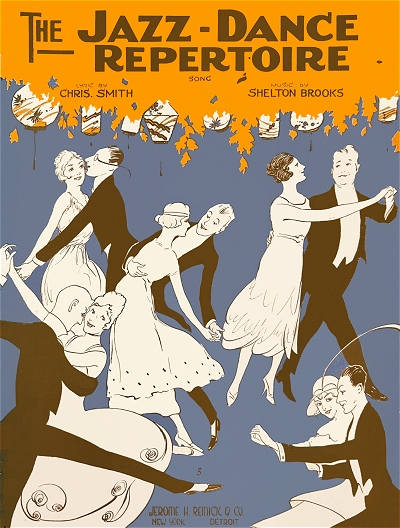

The Jazz Dance Repertoire [3]1921

Everybody's Going to See Mary Now [3]Mighty Day [3] Don't Talk About Me [14] 1922

Keep My Honey Here Just One Day MoreDaddy O'Mine Charleston Cutout [3,15] |

1923

Darktown Has a Gay White WayHouse Rent Ball You Better Build Love's Fire, or Your Sweet Mama's Gone Jazzbo Jenkins (She Stays Loved) From Then On (If Anybody Here Wants a Real Kind Mama) Here's Your Opportunity Original Blues I've Got What it Takes to Bring You Back Parisienne [16] 1924

Hoola Boola DanceWalk That Thing Ryelander Blues [17] Home Bound for Charleston, South Carolina [18] 1925

After All These Years [rewrite]A Fool and A Butterfly Your Jelly Roll is Good, But it Ain't As Good as Mine 1926

Smile Your Bluesies AwayBring Your Greenbacks When You Call Don't Drive Me Honey, From Your Door Steal My Man, I'll Throw Dirt in Your Face 1927

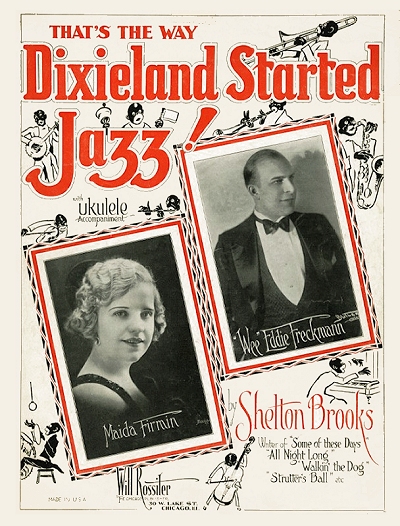

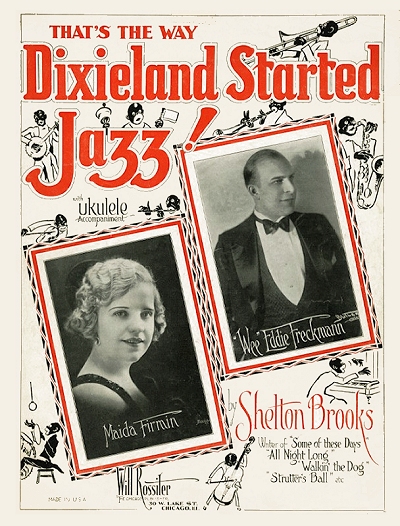

That's the Way Dixieland Started Jazz!Meditation Stop Dat Band [19] 1928

The Hole in the Wall1930

Don't Leave Your Little Blackbird Blue [20]1931

The Levy Low Down [21,22]1933

Swing That Thing1934

Happy-Go-Lucky Sam1935

She Can't Do That to Me1936

I Can't Carry On Without YouRomping on Rampart Rhythm Train [23] 1939

Jitterbugs Cuttin' RugsThru the Day and All Night Long [24] 1940

Two Hearts to Beat [23]

1. w/Matthew Marshall

2. w/Maruice Abrahams 3. w/Chris Smith 4. w/W.R. Williams 5. w/Lew Berk 6. w/William Vaughan Dunham 7. w/Howard Johnson 8. w/Harry T. Bunce 9. w/Sidney D. Mitchell 10. w/Fredric Watson 11. w/Grant Clarke 12. w/J. Russel Robinson 13. w/Casper Nathan 14. w/Gus Butler 15. w/Tim Brymn 16. w/Sam M. Lewis & Joe Young 17. w/Henry Troy 18. w/Nelson L. Kincaid 19. w/Perry Bradford 20. w/Porter Grainger & Joseph J. Jordan 21. w/Irving Mills 22. w/Benny Carter 23. w/Shelton Brooks, Jr. 24. w/Jo Trent |

Selected Discography Selected Discography | |

|

1921

Lost Your Mind [1]Darktown Court Room Murder in the First Degree [1] 1922

The Chicken TheivesCollecting the Rents Back Biting 1923

Not To-nightThe Family Quarrel The Third Degree When the Dixie Sun Goes Down It Takes Money to Cure My Blues I Got What it Takes to Bring You Back [2] Original Blues [2] New Darktown Judge Then I'll Go Into the Lion Cage 1924

Old VeteransBuddies You Got to Go That's Enough Pot of Gold You'll Be a Cousin Shy 1925

After All These Years [3]A Fool and a Butterfly [3] The Barber Shop Four Work Don't Bother Me The Spritualist The Lodge Meeting The New Professor Jail Birds 1926

After All These Years [4]Satisfyin' Papa [4] The Fortune Teller Domestic Troubles In My Southern Harem I Was Marching Through Georgia When You're Really Blue You Sure Am One Sick Man 1927

Who's Who in a Barber's Shop (1 & 2) [5]1928

Hard TimesLast Night

1. w/Regal Orchestra

2. w/Sara Martin [vcl] 3. w/Ollie Powers [vcl] |

Matrix and Date

[OKeh S-7870] 04/??/1921[OKeh S-7874] 04/??/1921 [OKeh S-7878] 04/??/1921 [OKeh S-70813] 08/??/1922 [OKeh S-70845] 09/??/1922 [OKeh S-71269] 02/??/1923 [OKeh S-71270] 02/??/1923 [OKeh S-71320] 03/??/1923 [OKeh S-71321] 03/??/1923 [OKeh S-71400] 04/??/1923 [OKeh S-71401] 04/??/1923 [OKeh S-72042] 11/??/1923 [OKeh S-72043] 11/??/1923 [OKeh S-72528] 05/??/1924 [OKeh S-72956] 11/05/1924 [OKeh S-72957] 11/05/1924 [OKeh S-72976] 11/??/1924 [OKeh S-72977] 11/??/1924 [Columbia 140248] 01/14/1925 [OKeh S-73167] 02/??/1925 [OKeh S-73168] 02/??/1925 [OKeh S-73212] 03/??/1925 [OKeh S-73215] 03/??/1925 [OKeh 73824] 12/10/1925 [OKeh 73825] 12/10/1925 [Columbia 141706] 02/17/1926 [OKeh 74053] 03/??/1926 [OKeh 74054] 03/??/1926 [OKeh 80133] 09/23/1926 [OKeh 80134] 09/23/1926 [OKeh 80135] 09/23/1926 [OKeh 80136] 09/23/1926 [OKeh 400791] 06/15/1928

4. w/Ethel Waters [vcl]

5. w/Ham & Sam [comics] |

While there has been plenty written on Shelton Brooks over the decades since he became famous, very little seems to have survived beyond contemporary accounts, and that which survives has often been in dribs and drabs, largely focused on his compositions (none of them instrumental piano rags). A deeper dive into his career and, in some ways, pioneering breakthroughs as a black entertainer AND songwriter reveals a variegated individual who accomplished more underneath the surface than may have been previously surmised. Known largely for his two most famous tunes and an association through one of them to Sophie Tucker, "Last of the Red Hot Mamas," there is much more to be discovered, especially concerning the regard he was given in many corners of the entertainment industry in its sophomore period. Hopefully this essay will give better context to Mister Brooks, both the good and the not so good, and raise his overall profile a bit when assessing popular music of the early 20th century.

The Boy from Canada

Shelton Brooks was the offspring of American parents, although he was born in Amherstburg, Ontario, Canada, a suburb of Windsor across the river from Detroit, Michigan. He was the seventh of eleven siblings born to Methodist minister Peter Brooks of Kentucky and Laura Ann Smith of Indiana. The other brothers and sisters included Peter, Jr. (2/4/1881), Lulu (1873), Daniel (1876), Ardena (1873), Evaline (12/22/1880), Peter Houston (1884), Ruby Kersey (1/19/1888), Kennetha (1/18/1889), Elizur (12/26/1894), and Claud (9/14/1897). The 1891 Canadian census showed the family living in St. Johns Ward in Toronto, Ontario. It is not clear if the Brooks had moved to Canada to escape the issues common to Southern blacks during the reconstruction years of the 1870s, but Peter and Laura were married in Colchester, Ontario in 1873. Peter's primary pulpit was at the Nazery African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church

According to a biographical sketch curated by Floyd G. Snelson from an interview in 1938 as part of the Federal Writer's Project:

[Shelton] began to play the organ before he could stretch his small legs to the bellows. With an elder brother to pump, he would sit for hours at the keyboard, learning instinctively to play even before he learned his alphabet. In his early youth [at least 15] when his family removed from Canada to Detroit, he had become so proficient at the piano that he was able to earn his living playing in cafés and parties…

His parents shared richly in this traditional fondness of the Negro for music, giving musical expression to their emotions through an organ of ancient vintage…

Years later, Brooks learned the fundamentals of music, mostly through the means of self-instruction, but he was considered a successful piano player, and was in great demand, long before he attempted to penetrate the mystery of written music. His playing was in the rhythmic pattern that came into vogue early in the Twentieth Century hailed as "ragtime", and eventually adopted by hosts of musicians, white and colored. He is generally known as one of the genuine leaders in the "ragtime"--"jazz" movement.

The 1901 Canadian census taken in Raleigh, Kent, Ontario, showed the family back near Windsor, with Peter, Sr., still working as a minister. Within a few months the family would relocate across the river to Detroit and remain in the United States. It is unclear if Shelton ever sought United States of America citizenship despite his parent's native status, as he was listed as a resident alien as late as the 1950 Federal census, and no other documents were found to contradict that status. There are also conflicting reports as to whether or not he learned the rudimentary elements of music notation, but there are indicators that he could at least read some aspect of scores, even if he did not write them. That he gained notoriety in later years for his work as an arranger further reinforces the probability of at least some musical literacy.

It is unclear if Shelton ever sought United States of America citizenship despite his parent's native status, as he was listed as a resident alien as late as the 1950 Federal census, and no other documents were found to contradict that status. There are also conflicting reports as to whether or not he learned the rudimentary elements of music notation, but there are indicators that he could at least read some aspect of scores, even if he did not write them. That he gained notoriety in later years for his work as an arranger further reinforces the probability of at least some musical literacy.

It is unclear if Shelton ever sought United States of America citizenship despite his parent's native status, as he was listed as a resident alien as late as the 1950 Federal census, and no other documents were found to contradict that status. There are also conflicting reports as to whether or not he learned the rudimentary elements of music notation, but there are indicators that he could at least read some aspect of scores, even if he did not write them. That he gained notoriety in later years for his work as an arranger further reinforces the probability of at least some musical literacy.

It is unclear if Shelton ever sought United States of America citizenship despite his parent's native status, as he was listed as a resident alien as late as the 1950 Federal census, and no other documents were found to contradict that status. There are also conflicting reports as to whether or not he learned the rudimentary elements of music notation, but there are indicators that he could at least read some aspect of scores, even if he did not write them. That he gained notoriety in later years for his work as an arranger further reinforces the probability of at least some musical literacy.After knocking around playing in bars and dance halls in Detroit, Shelton, who was now often going by the nickname "Shell," ended up in Chicago by mid-decade. By early 1907 he became part of the Pekin Theatre stock company, working as a comedian and an end man (a vaudeville term for two comedians who flanked the interlocutor and provided punch lines). Among his skills were his piano, dancing, comedy pianologues, and imitative singing. Part of his act was an imitation of famed Ziegfeld Follies and vaudeville comedian/singer Bert Williams. Shelton's tribute imitation was often commented about in reviews of shows he was in, to the point that when Williams and his partner George Walker were touring in the area, they stopped in to experience the act. While this could sometimes have less than amicable results, it was reported that Bert complimented the young comedian and commented with a laugh, "If I'm as funny as he is, I'm all right." Williams would continue to follow and comment on Brooks' career until his death in the early 1920s.

Williams would continue to follow and comment on Brooks' career until his death in the early 1920s.

Williams would continue to follow and comment on Brooks' career until his death in the early 1920s.

Williams would continue to follow and comment on Brooks' career until his death in the early 1920s.Shelton decided to try his hand at songwriting while at the Pekin, and finally landed a couple of pieces with Chicago publisher Will Rossiter in 1909. You Ain't Talking to Me, composed to lyrics by Matthew Marshall was advertised as a "hit" for the white vaudeville team of Clifford and Burke. That and Honey Gal soon became minor hits on the vaudeville circuit. Both songs were also taken up by Al Jolson early in his career just before he became a sensation on Broadway. That same year, Shelton was married to Lena Malinda Boyd on June 11 with good reason. Five months later she gave birth to a baby girl who died very soon after. Despite this tragedy, Shelton moved forward with bigger ideas in his head for both performing and writing.

The mild success of his prior tunes resulted in an invitation from Chicago publisher Harold Rossiter, Will's brother, to sign a contract for both Shelton and fellow songwriter Chris Smith in late 1910. They would eventually pen a few numbers together, including two in 1911 and 1912. However, Brooks had a tune rolling about in his brain that did not have any set lyrics. While working in Cincinnati, Ohio, (he also claimed it was on Beale Street in Memphis at times), he caught part of a lover's quarrel in a restaurant near the theater. As he later recalled, the angry and likely wronged girl stood up to leave and clearly told her beau, "Better not walk out on me, man!, for some of these days you're going to miss me honey." (In 1943, Brooks further elaborated on the tale, saying that the same woman made the papers when she shot the scoundrel who had wronged her in front of the same saloon, and that she didn't miss HIM!) Shelton quickly realized that this phrase would fit his melody, and going back to the theater he worked out most of the rest of the chorus within an hour, followed by two verses. Including it in his act it got a good response, and within a week it had been picked up by the Hodges Brothers for their vaudeville set at the Majestic Theatre in Chicago. However, publishers that he submitted the piece to did not have nearly the same reaction, and Shelton received several rejections, including, evidently, from Rossiter. Undaunted, he spent $35 to have 1,000 copies printed by the William Foster publishing firm, and started selling them wherever he could.

However, publishers that he submitted the piece to did not have nearly the same reaction, and Shelton received several rejections, including, evidently, from Rossiter. Undaunted, he spent $35 to have 1,000 copies printed by the William Foster publishing firm, and started selling them wherever he could.

However, publishers that he submitted the piece to did not have nearly the same reaction, and Shelton received several rejections, including, evidently, from Rossiter. Undaunted, he spent $35 to have 1,000 copies printed by the William Foster publishing firm, and started selling them wherever he could.

However, publishers that he submitted the piece to did not have nearly the same reaction, and Shelton received several rejections, including, evidently, from Rossiter. Undaunted, he spent $35 to have 1,000 copies printed by the William Foster publishing firm, and started selling them wherever he could.Among Shelton's acquaintances was a maid working for Ukrainian immigrant singer Sophie Tucker in her Chicago home. Encouraged by his publisher to initiate contact with Tucker, an introduction was made, and Brooks asked Tucker to consider the piece. He later mentioned that,

I was scared to death. There I was just starting out, and to me, Miss Tucker was even then a big star. I got up all my courage and saw her. She liked the song right away.

The tune appeared in her act at the White City Amusement Park within a day or so. Some of These Days became a staple for Sophie Tucker, and the eventual title of her autobiography, such was the association. It took her little effort to convince Rossiter, who had turned down the piece initially, to not only buy the copyright for $250, but promote it heavily, given the provision that it would exclusively be her stage property for a while. Based on her saucy performances of Some of These Days, it became a giant career boost for both Tucker and Brooks, and helped to cement his reputation as a composer.

Shelton and Lena, the latter who was involved on stage in his act with the Pekin touring company in 1910, were not located in that year's census, having been on the road in Cincinnati about the time of the enumeration. There were no mentions of Mrs. Brooks on stage after 1910. In March 1911, the same year that he introduced The Cosey Rag, Shelton became part of the My Friend from Dixie company in Chicago, working with actor John Leubrie Hill who had written the production. Leubrie would go on to form the Colored Vaudeville Exchange, and write At the Ball, That's All. Brooks was on the road with this company and other vaudeville troupes over the next several months. However, he had to leave the stage for a short while in 1912 due to "an attack of rheumatism." He would resume activity and touring later in the year. His composition All Night Long saw some traction with the public and on records and the stage.

Riding the Wave of Fame

The year 1913 would be more eventful for Shelton. Lena gave birth to Shelton Leroy, Jr., on September 23, 1913. Prior to that, the teaming of Brooks with fellow comedian and singer Clarence Bowen, formerly of the Georgia Campers troupe and at times referred to as "The Black Caruso," was announced in the New York Age, which noted that, "there is much genuine merit to their offering." However, this was followed up with a tepid review of their work in progress in the same paper on August 28, 1913:

The year 1913 would be more eventful for Shelton. Lena gave birth to Shelton Leroy, Jr., on September 23, 1913. Prior to that, the teaming of Brooks with fellow comedian and singer Clarence Bowen, formerly of the Georgia Campers troupe and at times referred to as "The Black Caruso," was announced in the New York Age, which noted that, "there is much genuine merit to their offering." However, this was followed up with a tepid review of their work in progress in the same paper on August 28, 1913:Messrs. Brooks and Bowen would have a big-time act if they inaugurated a number of important changes. As their skit now stands they make a heroic attempt to be comedians, when, as a matter of fact they are strong at piano playing, singing and dancing. Were they to appear in neat attire, without cork [blackface], play the piano sing and dance in their refreshing, way, their act would be highly entertaining from start to finish.

However, for some reason they try to be funny and waste a lot of valuable time. Shelton Brooks does some clever work at the piano and has a good singing voice. Clarence Bowen is still a sweet tenor singer, but does not sing enough. He has not lost any of his skill as a dancer. "Some of These Days" would be a better number for the orchestra to use when Brooks and Bowen make their first entrance. "The [Honky Tonky] Monkey Rag" has been used repeatedly by [the composer] Chris Smith in these parts.

Shelton composed another piece in 1913 that was less of an immediate hit, but found steady supporters through a variety of performers over the next several decades. I Wonder Where My Easy Rider's Gone told the story of "Miss Susan Johnson" who put her trust into a horse race jockey, betting all she had based on his tips. On that particular day "Jockey Lee" did not race a horse, but instead raced off into the sunset with her money, begging the question asked in the title. The song made enough of a ripple that it warranted an eventual direct answer by Shelton's acquaintance, W.C. Handy, who, in his own Yellow Dog Blues of 1914 noted that "He's gone where the Southern cross' the Yellow Dog," the reference to the "Southern" being the Southern Railway and the "Yellow Dog" being the much smaller Yazoo Delta Railroad, with their junction located in Moorhead, Mississippi. It wasn't long before both pieces were performed back to back in a variety of white and black vaudeville theaters.

I Wonder Where My Easy Rider's Gone told the story of "Miss Susan Johnson" who put her trust into a horse race jockey, betting all she had based on his tips. On that particular day "Jockey Lee" did not race a horse, but instead raced off into the sunset with her money, begging the question asked in the title. The song made enough of a ripple that it warranted an eventual direct answer by Shelton's acquaintance, W.C. Handy, who, in his own Yellow Dog Blues of 1914 noted that "He's gone where the Southern cross' the Yellow Dog," the reference to the "Southern" being the Southern Railway and the "Yellow Dog" being the much smaller Yazoo Delta Railroad, with their junction located in Moorhead, Mississippi. It wasn't long before both pieces were performed back to back in a variety of white and black vaudeville theaters.

I Wonder Where My Easy Rider's Gone told the story of "Miss Susan Johnson" who put her trust into a horse race jockey, betting all she had based on his tips. On that particular day "Jockey Lee" did not race a horse, but instead raced off into the sunset with her money, begging the question asked in the title. The song made enough of a ripple that it warranted an eventual direct answer by Shelton's acquaintance, W.C. Handy, who, in his own Yellow Dog Blues of 1914 noted that "He's gone where the Southern cross' the Yellow Dog," the reference to the "Southern" being the Southern Railway and the "Yellow Dog" being the much smaller Yazoo Delta Railroad, with their junction located in Moorhead, Mississippi. It wasn't long before both pieces were performed back to back in a variety of white and black vaudeville theaters.

I Wonder Where My Easy Rider's Gone told the story of "Miss Susan Johnson" who put her trust into a horse race jockey, betting all she had based on his tips. On that particular day "Jockey Lee" did not race a horse, but instead raced off into the sunset with her money, begging the question asked in the title. The song made enough of a ripple that it warranted an eventual direct answer by Shelton's acquaintance, W.C. Handy, who, in his own Yellow Dog Blues of 1914 noted that "He's gone where the Southern cross' the Yellow Dog," the reference to the "Southern" being the Southern Railway and the "Yellow Dog" being the much smaller Yazoo Delta Railroad, with their junction located in Moorhead, Mississippi. It wasn't long before both pieces were performed back to back in a variety of white and black vaudeville theaters.Brooks and Bowen would ply the boards on vaudeville circuits around the country from 1913 into 1917, appearing on the same bills as many well-known black entertainers, and occasional white ones as well. In most reviews, Brooks was called out for his comedic takes and imitations, as well as his fine playing and singing, while Bowen was noted for his singing and dancing. Shelton was still composing now and then, always a time-consuming endeavor when traveling around on a tour. He later recalled that he believed he was the first black performer to appear on the main stage at the storied Palace Theater vaudeville house in Manhattan. By 1915 he had moved from Chicago, settling the family in Queens, New York, across the river from the Manhattan theaters. The 1915 New York census showed him as an author rather than entertainer or actor, with he and Lena hosting her widowed mother Alice Boyd, who would remain with the couple into the 1940s.

The 1915 New York census showed him as an author rather than entertainer or actor, with he and Lena hosting her widowed mother Alice Boyd, who would remain with the couple into the 1940s.

The 1915 New York census showed him as an author rather than entertainer or actor, with he and Lena hosting her widowed mother Alice Boyd, who would remain with the couple into the 1940s.

The 1915 New York census showed him as an author rather than entertainer or actor, with he and Lena hosting her widowed mother Alice Boyd, who would remain with the couple into the 1940s.Shelton's next hit number was based on a popular dance during a time when a new animal dance would appear every month or so, often invented by the lyricist with instructions in the lyrics. In this case, it was Walkin' the Dog that made a splash during 1916. It was quickly adopted by many of his peers on the vaudeville circuits. The front cover dedication included one of his Chicago friends, Glover Compton, who evidently had later provided a theme used in the enduring hit Canadian Capers. But his next big standard would appear in 1917, and cemented Brook's fame for good.

While performing for and attending the Panama-Pacific Exposition on Treasure Island in San Francisco, California, in 1915, an event at which several attendees were first exposed to the music of Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton, Shelton was working in a theater when he was invited to a social gathering. It was held in the Chinatown section of San Francisco, but most of the attendees were reportedly "dark strutters," or black dancers. The events of that evening stuck with him, and by 1917 he had come up with the right tune and the right lyrics describing the dance. The result was The Darktown Strutters' Ball, and it was soon a jazz hit, one of the early pieces adopted and recorded by the all-white bands The Six Brown Brothers saxophone ensemble, and the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, both recordings released in May 1917. Despite it being an enormous success soon after its introduction, it was reportedly not an easy sell at first, according to this mention in the New York Dramatic Mirror of February 8, 1919:

Despite it being an enormous success soon after its introduction, it was reportedly not an easy sell at first, according to this mention in the New York Dramatic Mirror of February 8, 1919:

Despite it being an enormous success soon after its introduction, it was reportedly not an easy sell at first, according to this mention in the New York Dramatic Mirror of February 8, 1919:

Despite it being an enormous success soon after its introduction, it was reportedly not an easy sell at first, according to this mention in the New York Dramatic Mirror of February 8, 1919:After Leo. Feist had purchased the "Darktown Strutters' Ball," a report gained circulation to the effect that Phil Kornheiser could have acquired the number in manuscript form for a small advance. When quizzed about it, Phil replied:

"Whoever started that report got it all wrong. I never rejected the song. Shelton Brooks came in here one day to play the number for a woman headliner. He was trying to get her to introduce it. She listened to it, while I was in the room, and when Brooks had finished playing it she puckered up her lips as much as to say that she thought it was a piece of junk. Brooks' playing of it didn't impress me very much, and with the woman not being able to see anything in it. I didn't think much of it. I knew Brooks was looking for a publisher and I suppose if I had offered him a hundred in advance he would have let me have the song. That's all there was to the thing."

The original issuance was from Will Rossiter in Chicago, who had been a supporter of Shelton since 1909. However, the potential for this song to take off caused New York publisher Leo Feist to procure the rights for a rather tidy sum, releasing it with a similar but unfortunately more stereotyped cover. Subsequent sales of over three million copies warranted Feist's faith in the Brooks tune, and he made it back several times over. Since customers enjoyed it and the writer and publisher profited from it, everybody went away happy. Everybody except, perhaps, that lady who referred to it as a "piece of junk."

releasing it with a similar but unfortunately more stereotyped cover. Subsequent sales of over three million copies warranted Feist's faith in the Brooks tune, and he made it back several times over. Since customers enjoyed it and the writer and publisher profited from it, everybody went away happy. Everybody except, perhaps, that lady who referred to it as a "piece of junk."

releasing it with a similar but unfortunately more stereotyped cover. Subsequent sales of over three million copies warranted Feist's faith in the Brooks tune, and he made it back several times over. Since customers enjoyed it and the writer and publisher profited from it, everybody went away happy. Everybody except, perhaps, that lady who referred to it as a "piece of junk."

releasing it with a similar but unfortunately more stereotyped cover. Subsequent sales of over three million copies warranted Feist's faith in the Brooks tune, and he made it back several times over. Since customers enjoyed it and the writer and publisher profited from it, everybody went away happy. Everybody except, perhaps, that lady who referred to it as a "piece of junk."Bowen took ill in the fall of 1917, so Shelton continued for a time as a single. Clarence Bowen died on November 16, 1917, leaving Brooks without a partner. By 1918 he was working with Ollie Powers on the vaudeville circuits doing a blackface routine. (Ironically, many black entertainers, most notably Bert Williams during his time at the Ziegfeld Follies, worked on stage in blackface despite the obvious irony of the situation.) Shelton was not writing prolifically, but he got some numbers out into the public and on stage, including two written with white lyricists, I Want to Shimmie with Grant Clarke and Wake Me Up Cooin' the Blues with J. Russel Robinson. He also had a decent success with the song Jean from 1919, which would soon be popularized by bandleader Isham Jones. One further potential hit had the oversized title of Tell Me Why You Want to Go to Paree When You Can Get the Same Sweet Loving Here at Home. In the Music Trade Review of April 19, 1919, publisher Jack Glogau insisted that:

Shelton never wrote a bad one and you can bank all you've got that this one is a pip. This number is going to put all the 'parlez vous' songs in the shade.

In the fall of 1919 Shelton found a new partner in clarinetist Horace George, and they hit some of the theaters in New York, but appear to have done little in the way of touring in this post-war year. The New York Dramatic Mirror vaudeville critic made clear the nature of the act, singling out its star:

The New York Dramatic Mirror vaudeville critic made clear the nature of the act, singling out its star:

The New York Dramatic Mirror vaudeville critic made clear the nature of the act, singling out its star:

The New York Dramatic Mirror vaudeville critic made clear the nature of the act, singling out its star:Shelton Brooks, the clever negro song writer and singing comedian, has as a team mate one Horace George, a clarinet player, who blows a mean tune. Brooks is, however, the whole act, which is as it should be. It is a distinct pleasure to witness his work. He sings, accompanying himself on the piano, two of the best comedy songs we have heard in a long time. The act's climax is a medley of songs written by Brooks, among which was [Darktown] Strutters' Ball, played by the composer on the piano and George on his clarinet.

Their partnership would dissolve by June 1920. On his 1918 draft record, Shelton indicated that he was living in the Jamaica Estates section of Queens, and employed by the Keith vaudeville circuit. The 1920 enumeration showed much of the same information, and that his brother-in-law Ancil had joined the household. However, Shelton was the only one gainfully employed, listed as an actor and comedian rather than as a songwriter. That summer Brooks was out in his own again, but he would soon team up with singer and drummer Ollie Powers in a company that included blues singer Alberta Hunter. Working as the leading man opposite Hunter, Shelton and company toured with great success in a production of Canary Cottage well into 1921, and occasionally appeared with Powers as a duo in theaters like Proctor's in New York City.

In 1922, Lew Leslie's Plantation Revue, the first all-colored stage musical written by white composers Roy Turk and J. Russell Robinson, toured around the East and Midwest to great acclaim. In its cast was singer Florence Mills, the "Queen of Happiness." She and Shelton would do quite a bit of work together over the next few years until her death from tuberculosis in 1927. As her sometimes accompanist, it is possible he did some recording with Florence. It is known tha Brooks embarked on his own brief recording career with OKeh records starting in 1921. Most of the records he turned out over the next seven years would be pianologues or comedy sketches with some of his friends or colleagues. However, there were a few songs tucked in there as well. Two sides were cut for Columbia in 1925 with Shelton as the accompanist for Ollie Powers, and another pair on the same label the following year with him accompanying singer Ethel Waters but the rest were all on OKeh, including two blues songs with Sara Martin cut in 1923.

However, there were a few songs tucked in there as well. Two sides were cut for Columbia in 1925 with Shelton as the accompanist for Ollie Powers, and another pair on the same label the following year with him accompanying singer Ethel Waters but the rest were all on OKeh, including two blues songs with Sara Martin cut in 1923.

However, there were a few songs tucked in there as well. Two sides were cut for Columbia in 1925 with Shelton as the accompanist for Ollie Powers, and another pair on the same label the following year with him accompanying singer Ethel Waters but the rest were all on OKeh, including two blues songs with Sara Martin cut in 1923.

However, there were a few songs tucked in there as well. Two sides were cut for Columbia in 1925 with Shelton as the accompanist for Ollie Powers, and another pair on the same label the following year with him accompanying singer Ethel Waters but the rest were all on OKeh, including two blues songs with Sara Martin cut in 1923.Given the struggles that many African American composers and musicians had with publishing and getting a fair deal, despite the success of their music with the public, Shelton decided to pursue an avenue that some of his predecessors such as Will Marion Cook and W.C. Handy had attempted with some success. In late 1922 he teamed up with his peers Henry Creamer, a successful stage composer, and Will H. Vodery, who had worked with Shell as the orchestra leader for the Plantation Revue and was also a successful composer and arranger, to open a publishing concern in the Gayety Theater Building in Manhattan. Their first release was When the Sun Goes Down to Dixie, followed by a few others. However, other obligations including family and touring, in addition to the obstacles faced by black entrepreneurs of the time, made this enterprise a challenge to maintain at the very least. Beyond the announcement in The Billboard of December 16, 1922, virtually nothing was seen about this firm, which was short-lived. The plight of black composers had been underscored in that same publication on August 5, 1922 under the heading, A Dozen Colored Composers:

The Jack Mills Music Company is one concern that seems to measure merit rather than more personal elements [race] when considering a number offered for publication. The current catalog of that house contains compositions by no less than a dozen different musical geniuses of the race. It is only fair to the buying public among us that the identity of these artists and the concern that provides their opportunity should be known. The list of… composers follow:

Donald Heywood, Babe Thompson, Spencer Williams… [Henry] Creamer and [Turner] Layton… Dave Peyton… Shelton Brooks, Tim Brymn, Chris Smith… Lionel Belasco… Will Vodery… Maceo Pinkard… Alex Balledna… Cal Cornelius. [Note that there are 14 listed, not 12]

While the colored composers' work is to be found in practically every publishing house of note in the country, there are few houses with so large a representation of the race.

In July 1923, Shelton signed an exclusive contract with Mills, who would publish most of his works over the next few years. The year of 1923 further saw a tour of the Plantation Revue across the pond to England over the spring. After a brief return in July, some of the company returned to the United Kingdom and on continent. While there, Shelton was able to do a few singles on British vaudeville stages. He also wrote more material for his act, and a good amount of it was published throughout the year. Once back home in November, he went single again to great acclaim, with many comments such as, "There are few singers of darkey songs who can compete with Brooks and none who excel him on the vaudeville stage," and "His stories and his shuffling feet won great applause." By May 1924, he was ready to try publishing again, leasing another office in the Gayety building. It is unclear how long that concern lasted or what publications were issued from it. The only known piece he composed that year was the Hoola Boola Dance, which was a rather substantial for Perry Bradford and his Jazz Phools in early 1924, but appears to have not materialized in print.

After a brief return in July, some of the company returned to the United Kingdom and on continent. While there, Shelton was able to do a few singles on British vaudeville stages. He also wrote more material for his act, and a good amount of it was published throughout the year. Once back home in November, he went single again to great acclaim, with many comments such as, "There are few singers of darkey songs who can compete with Brooks and none who excel him on the vaudeville stage," and "His stories and his shuffling feet won great applause." By May 1924, he was ready to try publishing again, leasing another office in the Gayety building. It is unclear how long that concern lasted or what publications were issued from it. The only known piece he composed that year was the Hoola Boola Dance, which was a rather substantial for Perry Bradford and his Jazz Phools in early 1924, but appears to have not materialized in print.

After a brief return in July, some of the company returned to the United Kingdom and on continent. While there, Shelton was able to do a few singles on British vaudeville stages. He also wrote more material for his act, and a good amount of it was published throughout the year. Once back home in November, he went single again to great acclaim, with many comments such as, "There are few singers of darkey songs who can compete with Brooks and none who excel him on the vaudeville stage," and "His stories and his shuffling feet won great applause." By May 1924, he was ready to try publishing again, leasing another office in the Gayety building. It is unclear how long that concern lasted or what publications were issued from it. The only known piece he composed that year was the Hoola Boola Dance, which was a rather substantial for Perry Bradford and his Jazz Phools in early 1924, but appears to have not materialized in print.

After a brief return in July, some of the company returned to the United Kingdom and on continent. While there, Shelton was able to do a few singles on British vaudeville stages. He also wrote more material for his act, and a good amount of it was published throughout the year. Once back home in November, he went single again to great acclaim, with many comments such as, "There are few singers of darkey songs who can compete with Brooks and none who excel him on the vaudeville stage," and "His stories and his shuffling feet won great applause." By May 1924, he was ready to try publishing again, leasing another office in the Gayety building. It is unclear how long that concern lasted or what publications were issued from it. The only known piece he composed that year was the Hoola Boola Dance, which was a rather substantial for Perry Bradford and his Jazz Phools in early 1924, but appears to have not materialized in print.In late 1924, Shelton had a brief stint with the Lew Leslie show Dixie to Broadway, a rework to some extent of Plantation Revue. One reviewer of the production in November 1924, noted that Brooks was "perhaps the most keenly intelligent and one of the best Negro comedians living." However, he exited the production in December, noting that his salary was insufficient to his contributions. Brooks reconnected with Ollie Powers again, and they briefly went on the road across a vaudeville circuit. By February 1925 they became part of the repertoire company at the Club Alabam' in New York, playing there on and off over the next year or so. In 1926, Brooks wrote a few short revues that were sent out on the black TOBA (Theatre Owners Booking Association) circuit around the East and Midwest. He also did some condensed versions of the routines on Okeh Records with Ollie. Brooks and Powers would continue to make a splash in vaudeville houses well into late 1927. A review of one of his appearances in Syracuse, New York, by Franklin H. Chase in the Syracuse Journal of December 19, 1927, greatly lauded his performance acumen:

He also did some condensed versions of the routines on Okeh Records with Ollie. Brooks and Powers would continue to make a splash in vaudeville houses well into late 1927. A review of one of his appearances in Syracuse, New York, by Franklin H. Chase in the Syracuse Journal of December 19, 1927, greatly lauded his performance acumen:

He also did some condensed versions of the routines on Okeh Records with Ollie. Brooks and Powers would continue to make a splash in vaudeville houses well into late 1927. A review of one of his appearances in Syracuse, New York, by Franklin H. Chase in the Syracuse Journal of December 19, 1927, greatly lauded his performance acumen:

He also did some condensed versions of the routines on Okeh Records with Ollie. Brooks and Powers would continue to make a splash in vaudeville houses well into late 1927. A review of one of his appearances in Syracuse, New York, by Franklin H. Chase in the Syracuse Journal of December 19, 1927, greatly lauded his performance acumen:If I had been putting up the electric light in front of Keith's for this first half week, it is Shelton Brooks' name that would have stood out first. And the applause of the audience showed that it has a similar opinion. Shelton is only a minstrel monologist, and they are all supposed to be in graveyards or heading musical shows like [Al] Jolson's or [George] Jessel's. But Brooks has the real comedy darky looseness in movement and mirth, and he puts over a story without departing from his character. In that is his art.

Not long after the death of Florence Mills in 1927, Brooks lost yet another partner when Ollie Powers took ill in March 1928 while they were on the road with Billy King in Chicago. Powers died on April 14 at Cook County hospital following an operation for diabetes mellitus. The notice of his death in The Pittsburgh concluded that "Mr. Powers was the most gifted singer in the alto-tenor class of the

present day." After a brief hiatus, Shelton returned to his single act, but by September 1928 he turned to the role of producer with a show at the Lafayette theater New York. According to an announcement in the New York Age of September 15, 1928:

It is called "Nifties of 1928" and was produced by the world-famous musical composer and comedian Shelton Brooks.

"Nifties of 1928" is the answer of the colored theatre owners to the demand all over the country for a better type of show. From all reports, it is one of the finest shows ever organized. Supporting Shelton Brooks are Lena Wilson, Hunter and Warfield, St. Clair Dotson and Yvetter, Wilbur White and Chick Marguerite, Billy Hayes and King Hunter. Most of these artists have not been East in years. Then there is a chorus of twelve girls—recruited in Chicago and New York—said to be prettier and faster than anything Harlem has yet seen.

Surviving the Great Depression

|

As the economic downturn of the 1930s loomed, Shelton still had his focus set on expanding his work on stage, and produced the show Brown Buddies in the fall of 1930, sharing songwriting credit with Joe J. Jordan and Millard Thomas. Among the entertainers in that show was the dancer, Bill "Bojangles" Robinson and singer Adelaide Hall. Some of them had been part of Lew Leslie's Blackbirds company that produced several shows around that time. Shelton tagged along with them over the next few years, but mentions of him on stage were greatly diminished as the Great Depression grew deeper. With less spending money available, most Americans dropped entertainment outside of radio in favor of survival, and for a time, the black entertainers were hardest hit. However, as they historically did not all receive the same compensation as their white counterparts (with a few exceptions such as Thomas "Fats" Waller, they were able to still find some gigs based on their acceptance of a smaller cut of the overall take. It is unclear if Shelton actually got to the point of being destitute during this time, but a cryptic item found in a Walter Winchell column from August 1935 does suggest that possibility:

Sophie Tucker's theme song, "Some of These Days", was written 18 [sic] years ago by Shelton Brooks, a colored lad, whom Sophie had never met. In the old days. Brooks was as popular as Sophie. She met him on Broadway last week. and things were not too happy for him… So grateful is the star to the man who authored her famous encore arouser, she has taken him under her wing and will see to it that Shelton Brooks no longer worries about anything… It's big things like that that can get into this little column any time.

Whether or not that was Tucker embellishing the facts a little bit is unknown. However, things did start to pick up for the veteran performer in 1937, and he spent quite a bit of time working at the Little Harlem venue in Buffalo, New York during the winter and spring. His fame was enough that in 1938 as part of the Roosevelt administration's efforts to support the arts and employ more people, an article was written on Shelton for the Federal Writer's Project based on interviews conducted by its writer, Floyd G. Snelson. A distilled excerpt, from which some information was already used in this article, is included here, giving some clarity as to how Brooks navigated the economic issues of the decade:

Among the many unsung notables in the musical world who should be known by their works, or rather their works should be known along with then, is no other than the erstwhile pioneer Shelton Brooks…

In later years, "Shell" as he is familiarly known to his friends became a celebrated vaudeville entertainer, appearing in the finest and best theatres throughout the country and abroad.

With the passing of vaudeville he has devoted himself in more recent years to composition of music.

|

Brooks became a member of [ASCAP] in 1929, when sales of sheet music and phonograph records were beginning to decline with the expansion of the radio for musical entertainment. Throughout the machinery of this society, Brooks received a substantial revenue for use of his compositions in public performances for profit, it being the Society's prime object to protect its members' performance rights from infringement. [ASCAP]… has a limited number of Negro members, among whom is W. C. Handy, originator of "St. Louis Blues" which is perhaps the only song composed by a Negro to rival Brook's masterpieces. The Society has secured millions of its members, and it struggled for years against opposition until the rights of its members under the copyright law were thoroughly clarified by numerous Supreme Court decisions…

In recent years Brooks has made composition and musical arrangement his chief occupation and source of income, and is now enjoying a comfortable livelihood. He has done considerable travelling with the Irvin C. Mille productions as master of ceremonies and doing his old act of song and mimicry.…

He is married and lives with his wife and son Shelton Jr., the latter also a splendid musician, following the footsteps of his illustrious father. Owns his own home for many years, located at… Jamaica Long Island, New York City. He spends his evenings at a popular Broadway Hof brau at 60th and 8th Avenue, where he entertains the sporting fans of Madison Square Garden.

The younger Shelton was, indeed, now working in music, both as part of a swing band and as a composer. He co-composed at least two known works with his dad, including Rhythm Train in 1937 and Two Hearts to Beat in 1940. Another article that included more of the elder Shelton's point of view of current musical trends appeared in the Long Island Daily Press of February 11, 1939:

The "Father of Swing" is slightly bewildered by the antics of his offspring. Seated in his comfortable South Jamaica home, the almost middle-aged Negro composer… complained that what is called swing today isn't really swing.

"These new bands are so busy trying to put extra flourishes in the songs and make it sound 'hot' that they lose track of the melody," he objected. "You can tune in the middle of a song on the radio and never know the name of it until the announcer tells you what the band was playing.

Most of the new swing arrangements sound alike too. The bands use the same tricks, and then the melody is destroyed. It doesn't float through the way it used to when bands used sweet instruments like oboes, violins and cellos." …

|

Although many of the younger "jitterbugs" believe [Some of These Days] to be a new song, it has been consistently popular since it was written. Unlike other old songs, it never died out to return in the spotlight years later… Brooks remembers many exciting adventures in old-time vaudeville, but he's reluctant to discuss them. He can be persuaded to tell of his appearance with Charlie Chaplin in Hammerstein's Music Hall when Chaplin was rich on $60 a week. He'll also tell you of Joe E. Brown's juggling act and Douglas Fairbanks' capers.

… Brooks, whose latest appearances was only two months ago with Ted Lewis, doesn't believe vaudeville is dead.

"For one thing, if vaudeville dies, where will the radio comedians come from?" he demanded. "Every good radio comic was once in vaudeville. Vaudeville is the training ground for plenty of other things, too. It's the next generation that has me worried. Where will tomorrow's radio comics come from?" …

The younger Brooks, who plays in orchestras, reads music. Although he adds his own variations to the songs, his playing doesn't always satisfy his father. When Father is in another room and hears his son play a simple chord where he knows another would sound better, he can only call out, "Drop your hand, Junior," or "Raise your left hand, Junior." The world of notes remains a mystery. Melody, however, is something Brooks knows instinctively.

"The new songs aren't like the old ones," he laments. "Nowadays a song writer sits down and says, 'I'm going to write a song.'. He lifts a bar from an old rag-time song, another from perhaps one of the Hungarian rhapsodies, and—well, he just steals music," he explained. "This swing of theirs is a lot of foolishness. There's no real body or rhythm to it." …

The seemingly grouchy old-timer went on to talk about liking gangster films because the gangsters always got what was coming to them [which was literally part of the motion picture code of the period], and that he wanted to get cracking on songwriting again. However, only one more copyright was found from 1940, so if he was writing, he wasn't getting them published. In fact, Brooks took a much different direction—one that was westward, and in the summer of 1939, he moved west to California to see about getting in with the motion picture crowd. The 1940 enumeration taken in Los Angeles on Hooper avenue showed him as an actor in motion pictures, and Shelton, Jr., as a musician playing for motion pictures. Movies would, indeed, be his next chapter, albeit brief and, within the black community, perhaps a bit controversial.

Hollywood, Race, Representation and Nostalgia

From the late 1930s forward, there were many efforts to have a better representation of race on celluloid, and some concessions from studios taking a new look at who their audiences were and the revenue they could provide. To that end, Hollywood made some advancement, as it were, when, at the 1940 Academy Awards, actress Hattie McDaniel won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress in Gone With the Wind, the first of her race not only to win, but to even be nominated. The NAACP had contributed to that success and some elevation of status by insisting that producers keep certain depictions from the book out of the film, and to eliminate the use of the offensive "nigger" epithet. That effort was pushed back a bit by the use of the term "darkie," but it was still a positive step in both portrayal and treatment of black Americans. This was the world into which a stage actor and singer who had engaged in vaudeville and minstrelsy while ironically wearing blackface tried to enter, but was met with only limited success.

Shelton's music had been used in sound films going back to Al Jolson's The Singing Fool (1928), with Some of These Days appearing in Scarface (1932) and additional music in the black-centric film Harlem is Heaven (1932).

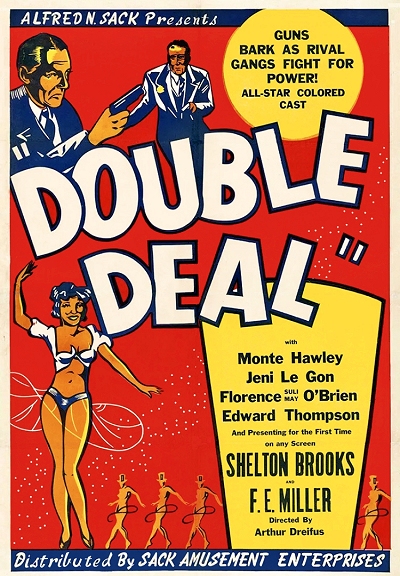

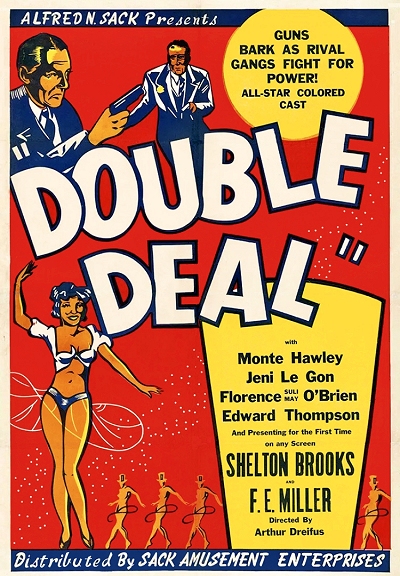

However, his considerable stage talent should have made him a natural for the camera, especially his Bert Williams impersonation. But the vaudeville style of acting often perpetuated the stereotypes that more socially conscious black Americans were trying to squelch. Double Deal was essentially a gangster melodrama with an all-black cast. Shelton's role was minor, playing a nightclub singer. As the story was played seriously, it was well-received overall and garnered many good reviews, as well as filling theater seats. Brooks, who had contributed two compositions to the soundtrack and performed one, Hole in the Wall from 1928, was not singled out given his minor role, but he was now in the movies.

|

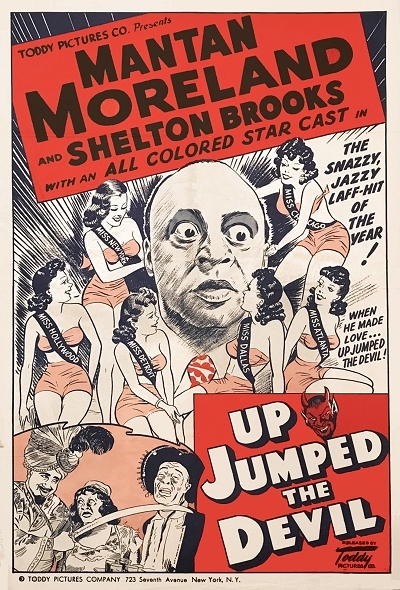

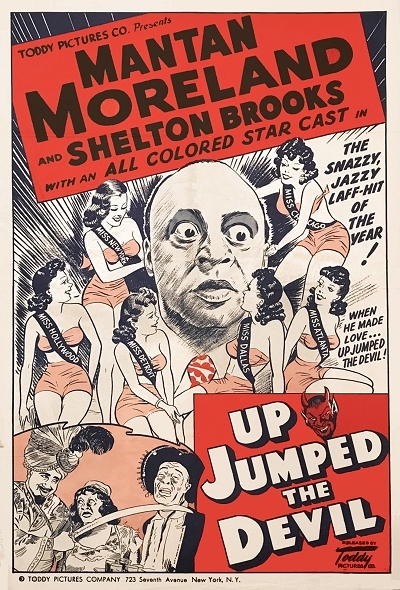

In early 1940 it was announced in the California Eagle, a Los Angeles-based black community newspaper, that Brooks was writing a screenplay based on his hit song The Darktown Strutters' Ball. The film never saw release, but a four-minute short of the piece performed by a vocal group, The Charioteers, was released in 1942. However, he did get his big chance in 1941 with Up Jumped the Devil. Starring in this film were Mantan Moreland and Shelton as two ex-convicts Washington and Jefferson, of which the names more or less forecast the tone of the story. They were just released from prison, scheming to find work to avoid going back to incarceration for vagrancy. One of the plot devices has them seeking work as a butler (Brooks) and maid (Jefferson in drag), and trying to thwart a con on their new employer by one of their former prison mates. The film was rife with stereotypical tropes and antics, along with dialect that many black leaders of the time were trying to avoid. A review by critic Almena Davis in the Pittsburgh Courier of September 19, 1941, gives a scathingly dim assessment of the end product.

Hollywood's Newest Film A Disgrace To The Race

Somewhere along the line, this reviewer got the idea that one of the purposes of all-colored movies is to get away from the stereotyped roles handed Negroes by the major studios, and show the race in a generally truer and more flattering light.

and show the race in a generally truer and more flattering light.

and show the race in a generally truer and more flattering light.

and show the race in a generally truer and more flattering light.After previewing the latest all-colored flicker to come off Sunset boulevard Monday night, I have arrived at the conclusion that I was dead wrong. Apparently, the purpose of all-colored movies is to allow some second rate Hollywood nabob with a few thousand dollars the opportunity of making capital (or more exactly, quadrupling said capital), out of the desire of the Negro to see his own in screen portrayals; out of the Negro's genuine talent for low comedy; and the white man's chortling delight in "Uncle Tom."

The picture previewed was a Jeb Bueil production, "Up Jumped the Devil." It was directed by William Xavier Crowley, who has to his discredit several such efforts, and written by white writers with a copy of Stephen Foster in one hand and "Uncle Tom's Cabin" in the other. The actors are several well known "names" that should have known better, but (I am resigned) will never learn now, namely: Mantan Moreland, Maceo Sheffield, Shelton Brooks, Clarence Brooks and Florence O'Brien…

Any Negro has the right to set the entire race back 60 years in 60 minutes of reeling film, and there's nothing we who resent it can do except stay away from the theaters where such pictures are shown, which we should certainly do droves!

Briefly, the film, criminally written, woefully directed, badly recorded and poorly photographed, concerns the efforts of two comedians (Shelton Brooks and Mantan Moreland) to get a job and stay out of jail. Moreland is an unregenerate sinner with a pair of loaded dice and an itch to use them. Brooks is his sorely tried foil.

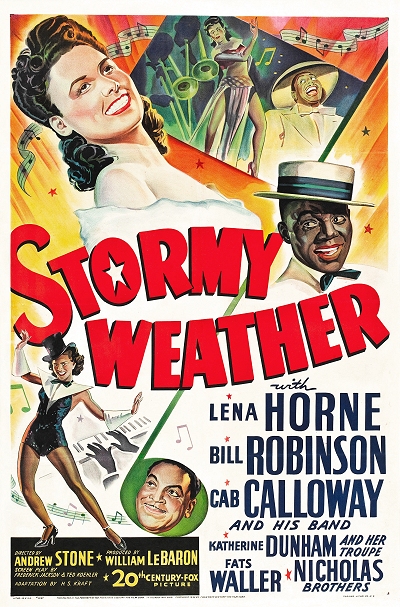

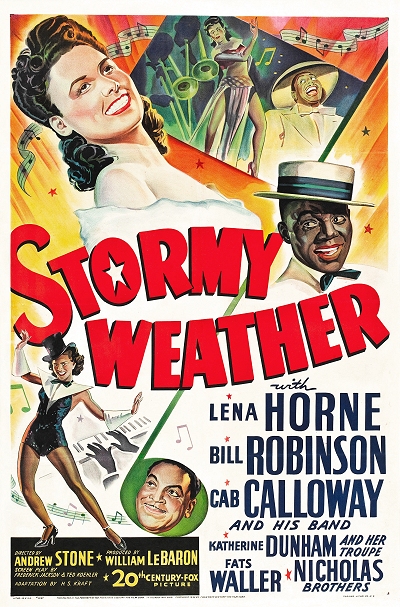

In the interim, Shelton had traveled to both San Francisco and New York World's Fairs in 1940, where he was honored for his contributions to American music. While in New York City in 1942 he appeared at the now-legendary Apollo Theatre in Harlem. Back in Hollywood, Brooks had a much smaller role in the subsequent Mantan Moreland film, Professor Creeps from 1942. However, the next film project that initially involved Shelton would fare much better, and become a classic, albeit without him. It was announced in January 1943 that Brooks was cast in the upcoming 20th Century Fox film Stormy Weather, a story which recounted many famous characters of the black show business community going back to James Reese Europe in the late 1910s. The vehicle was greatly successful due to the star power of Bill Robinson, Cab Calloway, Thomas "Fats" Waller, who would die within a few months, and Lena Horne, who did a lovely take on the centerpiece production of the title tune. Shelton was tapped to play the part that helped put him on the show business map, namely that of Bert Williams. Whether or not he actually went in front of the cameras for the production is unclear, but neither Bert nor Shelton were seen in the end product, although his piece The Darktown Strutters' Ball did make the cut for one scene.

However, the next film project that initially involved Shelton would fare much better, and become a classic, albeit without him. It was announced in January 1943 that Brooks was cast in the upcoming 20th Century Fox film Stormy Weather, a story which recounted many famous characters of the black show business community going back to James Reese Europe in the late 1910s. The vehicle was greatly successful due to the star power of Bill Robinson, Cab Calloway, Thomas "Fats" Waller, who would die within a few months, and Lena Horne, who did a lovely take on the centerpiece production of the title tune. Shelton was tapped to play the part that helped put him on the show business map, namely that of Bert Williams. Whether or not he actually went in front of the cameras for the production is unclear, but neither Bert nor Shelton were seen in the end product, although his piece The Darktown Strutters' Ball did make the cut for one scene.

However, the next film project that initially involved Shelton would fare much better, and become a classic, albeit without him. It was announced in January 1943 that Brooks was cast in the upcoming 20th Century Fox film Stormy Weather, a story which recounted many famous characters of the black show business community going back to James Reese Europe in the late 1910s. The vehicle was greatly successful due to the star power of Bill Robinson, Cab Calloway, Thomas "Fats" Waller, who would die within a few months, and Lena Horne, who did a lovely take on the centerpiece production of the title tune. Shelton was tapped to play the part that helped put him on the show business map, namely that of Bert Williams. Whether or not he actually went in front of the cameras for the production is unclear, but neither Bert nor Shelton were seen in the end product, although his piece The Darktown Strutters' Ball did make the cut for one scene.

However, the next film project that initially involved Shelton would fare much better, and become a classic, albeit without him. It was announced in January 1943 that Brooks was cast in the upcoming 20th Century Fox film Stormy Weather, a story which recounted many famous characters of the black show business community going back to James Reese Europe in the late 1910s. The vehicle was greatly successful due to the star power of Bill Robinson, Cab Calloway, Thomas "Fats" Waller, who would die within a few months, and Lena Horne, who did a lovely take on the centerpiece production of the title tune. Shelton was tapped to play the part that helped put him on the show business map, namely that of Bert Williams. Whether or not he actually went in front of the cameras for the production is unclear, but neither Bert nor Shelton were seen in the end product, although his piece The Darktown Strutters' Ball did make the cut for one scene.Shelton was seen in one more feature in 1945, Adventures of Kitty O'Day, but it was more of a token black character role with a white cast. Then he more or less dropped off the cinema map for a time during and after World War II. However, prior to that, in 1942, Shelton had been brought into Ken Murray's Blackouts which was based at the Hollywood Playhouse (a.k.a. the El Capitan) in Hollywood. It was an old fashioned revue reminiscent of vaudeville shows, and featured a number of Hollywood actors and performers, both black and white (and even Desi Arnaz), when they were not otherwise engaged in films. Brooks was a stock mainstay of the company through around 1949. There was one engagement of the Blackbirds company in New York City for seven weeks after the war, but for the most part they stayed in Los Angeles. The group was occasionally seen on early television broadcasting, but it is unclear if Shelton was any part of that. In 1949, he worked briefly with Shelton, Jr. in a skit at the theater.

Struttin' Into the Sunset

The 1950 census found Shelton and Lena residing in Fontana, San Bernardino County, just east of Los Angeles, listed as an actor and songwriter for movies and stage, a minor exaggeration at best. He would make a small screen appearance on May 16, 1950, featured on the Ralph Edwards show This is Your Life, a celebration of his history in the entertainment world. There was also a plan announced in late 1952 to feature his character, played by Billy Daniels, in a film based on the life of Sophie Tucker, Some of These Days, a project that was ultimately shelved. In 1953, Sophie Tucker appeared on the Ed Sullivan variety show and gave a heartfelt shout out to her musical benefactor, as relayed in the Pittsburgh Courier of December 12:

Many years ago the dynamic Sophie Tucker hitched her wagon to a star—a star in the form of a song, "Some of These Days," that showcased her act and in later years mirrored her philosophy of life. The "last of the red hot mamas" is still going strong and she still thinks so much of "Some of These Days" that she wants it played at her funeral.

In a rousing tribute to Composer Shelton Brooks on Ed Sullivan's "Toast of the Town" television show last week, Sophie Tucker called upon all her showmanship to give credit to the composer of "Some of These Days" and she socked it over in her own inimitable style. The great entertainer, whose career has spanned several eras of show business, including vaudeville, movies, radio and television (and today all three), virtually stole the show and by so doing revived the name of Shelton Brooks, who gave her "Some of These Days," a song Miss Tucker has kept alive since 1910, or thereabouts.

In most cases, singers gain more fame than composers of the songs they project. The same, in a sense, is true of Shelton Brooks… At last report, Mr. Brooks is living in Fontana, Calif., and doesn't seek the limelight he once enjoyed.

Somewhere in these United States "Some of These Days" is played every night, because as long as Sophie Tucker is around, it will be played—and people will remember Shelton Brooks as the man who gave the world a song that meant a lot of things to a lot of people, according to what they read into the lyrics…

For the most part, Brooks was retired and living off his royalties by the early 1950s. He made occasional appearances for old-time music gatherings,

which were not uncommon during the decade when honky-tonk piano and old-time music was readily found in record stores and heard on the radio and television shows. The 1960s had no overt mentions of the composer, but an event in 1971 put him back in the news, however briefly, as recounted in the [New York] Amsterdam News of Jun 29:

|

Three surviving members of a fast-disappearing generation, EUBIE. BLAKE-88; SHELTON BROOKS-84 and IVAN HAROLD BROWNING-80, were recently reunited in Canoga Park, California. The composers, who have long occupied a prominent spot in the world of entertainment since the early l900’s, took turns at the piano, sang favorite songs and did a lot of reminiscing. Mr. Brooks, composer of "Dark Town Strutters' Ball" and "Some of These Days," wrote much of A1 Jolson’s material as well as special material for various Ziegfield "Follies." His "Easy Rider," written 50 years ago, will be featured on a forthcoming Tom Jones television special.

The trio also headlined a ragtime concert at the Wilshire Ebell Theater in Los Angeles around that same time, which this author was fortunate enough to attend at a young age, ultimately meeting Eubie Blake, but not Brooks. This brought Shelton to the attention of Tonight Show host Johnny Carson who hosted a television special highlighting what he called the "Social Security Bracket" group of performers. Featured along with Brooks on the Sun City Scandals were such well-known names as Eddie Foy, Jr., Ethel Waters, Gene Sheldon, Bette Davis, Harry Ruby and Irving Caesar. It was his last known public appearance.

Living at that time with his son in Winnetka in the southwest corner of the San Fernando Valley, California, Shelton passed away on September 6, 1975, at the age of 89, and was laid to rest at Rose Hills Memorial Park. At his funeral a 13-piece second line-style jazz band played the traditional New Orleans spiritual Just a Closer Walk With Thee in a dirge-like fashion, then concluded with Some of These Days and The Darktown Strutters' Ball as full on raucous celebratory jazz. Brooks was largely remembered for his two biggest hits in the few obituaries that were printed, then seemingly all but forgotten except for his name. Two generations later his music is still being performed and recorded on a regular basis, rediscovered by a new batch of ragtime music artists and fans. Ultimately, the Boy from Canada made a difference in the world of entertainment on at least some of these days, if not most.

The majority of information for this essay came from hundreds of newspaper articles from 1905 to the early 2000s, most of them during Shelton's active career. The rest is from Canadian and United States government sources such as enumerations, marriage, birth and draft records, plus scant information from IMDB.com.