Thomas Wright "Fats" Waller (May 21, 1904 - December 15, 1943) | |

Selected Compositions Selected Compositions | |

|

1922

Wild Cat Blues [1]1923

All AloneIt Seems To Me Done Gone Mad Don't Want You No More Blues Never Die 1924

Friendless BluesOriental Tones Slaving [1] Flat Tire Papa, Mama's Gonna Give You the Air [1] Old Fashioned Susie's Blues [1,3] Sweet Baby [1] Mandy, I'm Just Wild About You [1,5] Hello Atlanta Town [1,5] Ramblin' Papa Blues [2] Bloody Razor Blues [2] Bullet Wound Blues [2] That Blue Strain [2] I May Be a Little Green But I Ain't No Fool [2] An Awful Lot My Gal Ain't Got, But What She's Got, She's Got an Awful Lot [2] My Sweet Baby Irene [2,3] Ice Cold Papa, Mama's Gonna Melt You Down [3] Call the Plumber In [3] My Jamaica Love [3] Shut Yo' Mouf [3] The Short Trail Became A Long Trail [3] When You're Tired of Me Just Let Me Know [3] Rock Me Just as a Sweet Daddy Should [3] Any Day the Sun Don't Shine [3] In The Springtime [5] That's My Man [5] My Man Cures the Blues [5] Strollin' Round the Town [5] What Can Be Wrong With Me? [5] In My Baby's Eyes [5] I'm Going Right Along [5] Please Take Me Back [5] In Harlem's Araby [5] My Baby's Coming Back Home [5] Sweetie Don't Grow Sour on Me [w/Charles O'Flynn] Strivers Row [w/Jack Moore] Please Tell Me Why [w/Ed Adams] 1925

Camp Meetin' StompWallerin' Around House Party Stomp [Alligator Crawl?] Kiss Me Again [1] The Heart That Once Belonged To Me Now Belongs to Somebody Else [1] Squeeze Me (The Boy in the Boat) [1] Brother Ben [2] Workin' Woman Blues [2] Ball and Chain Blues [3] Anybody Here Want to Try My Cabbage? [3] Home Alone Blues [w/John Homes] 1926

Chinese BluesLevee Land Beethoven's Sangwattni Congo Lou Henderson Stomp Harlem Black Dispatch (c.1926) Old Folks Shuffle [1] Crazy 'Bout the Man I Love [1,2] Lonesome One [1,3] Midnight Stomp: The Stomp of Stomps[1,7] That Struttin' Eddie of Mine [1,2,9] Señorita Mine [1,2,9] Charleston Hound [1,2,9] Georgia Bo-Bo [5] That Florida Low Down [5] [w/J. Fred Coots] Great Scott [w/Henry Troy] 1927

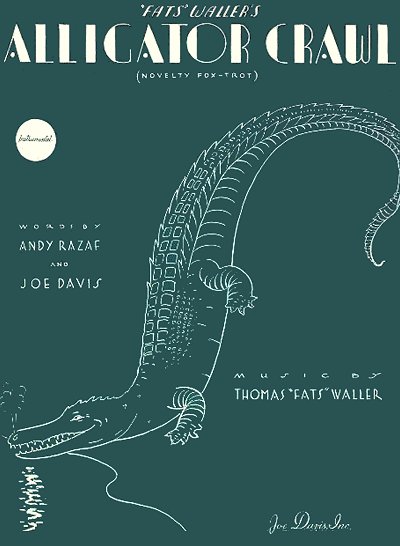

Blue Black BottomMeditation Fat Man Blues The Digah's Stomp Alligator Crawl Sloppy Water Blues Soothin' Syrup Stomp A Darkie's Lament Lenox Avenue Blues Long, Deep and Wide Florence Fats Waller Stomp [10] [w/Charlie Irvis] The Rusty Pail Blues Messin' Around with the Blues [w/Phil Worde] Shake Your Feet [11] Wringin' and Twistin' [5] [w/Frank Trumbauer] I'm More Than Satisfied [w/Raymond Klages] White Man Stomp [1] I'm Goin' Huntin' [w/James C. Johnson] Nobody Knows [12] [w/Bennett Carter] Please Take Me Out of Jail [10] Savannah Blues [10] Come On and Stomp, Stomp, Stomp [11] [w/Chris Smith] St. Louis Shuffle [13] Hop Off [1,7] (c.1927) 1928

Monkey TalkHog Maw Stomp Lion's Roar Whiteman Stomp [1] I Hope You're Satisified [1] If You Like Me, I Like You [1,2] Lovie Lee [3] Willow Tree [3] Got Myself Another Jockey Now [3] One O'Clock Blues [12] [w/Walter Bishop] Candied Sweets [13] From Keep Shufflin': Musical Cho'late Bar [3] Washboard Ballet [3] [w/Henry Creamer] How Jazz Was Born [3] 1929

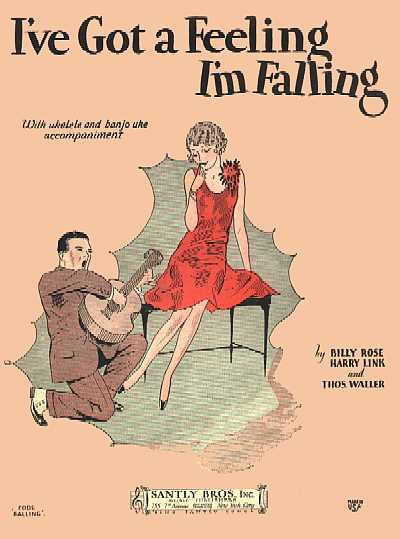

Goin' AboutWaiting at the End of the Road Ridin' But Walkin' No Wonder Minor Drag A Handful of Keys Smashing Thirds Numb Fumblin' I Need Someone Like You Gladyse Trouble Touchdown Valentine Stomp Harlem Fuss Freeze Out Won't You Get Off It, Please? I'm Not Worrying [1] Why Am I Alone with No One to Love? [2,3] Waltz Divine [3,4] Laughing Water [3,4] Alone and Blue [3,4] My Man is Good for Nothin' But Love [3,4] Lookin' Good But Feelin' Bad [8] Lookin' For Another Sweetie [8] Six or Seven Times [11] I've Got A Feeling I'm Falling [14] [w/Billy Rose] That Was My Own Idea [w/Billy Moll] Load of Coal: Musical [3] Honeysuckle Rose [3,4] Load of Coal My Fate is In Your Hands Zonky Heavy Sugar Find Out What They Like My Man Is Good for Nothing But Love [3,4] Connie's Hot Chocolates: Musical [3,4] Song of the Cotton Fields Sweet Savannah Sue Say It With Your Feet [3] Ain't Misbehavin' Goddess of Rain Dixie Cinderella Black and Blue (What Did I Do to Be So) That Rhythm Man Can't We Get Together? Redskinland Jazzlips Snakes Hips (Snake Hip Dance) Off Time Jungle Jamboree 1930

Asbestos (c.1930)Blue Turning Grey Over You [3] Prisoner of Love [3] Gone [3,14] Rollin' Down the River [9] Keep a Song in Your Soul [15] 1931

My Feelin's Are HurtAfrican Ripples That's All Old Yazoo Take It From Me (I'm Takin' To You) [9] I'm Crazy 'Bout My Baby [15] Little Brown Betty [15] Heart of Stone [15] The Ice Man Lives in an Ice House [w/R. Duromo & Elmer S. Hughes] 1932

Glorie's Good Mornin'Where the Dew Drops Kiss the Morning Glories Good Mornin' [2] The Blowin' of the Breeze Blew You Into My Arms [2] You're My Ideal [2] Do Me a Favor, Lend Me a Kiss [2,3] Oh, You Sweet Thing [3] It's You [3] Concentratin' (On You) [3] Buddie [3] When Gabriel Blows His Horn [3] How Can You Face Me? [3] Strange As It Seems [3] Oh! You Sweet Thing [3] I'm Now Prepared to Tell the World It's You [3] Gotta Be, Gonna Be Mine [3] Keepin' Out of Mischief Now [3] |

1932 (Cont)

Radio Papa, Broadcastin' Mama [3,14]Lonesome Me [3,16] If It Ain't Love [3] [w/Donald Redman] I Didn't Dream it was Love [16] [w/Elliot Grennard] Only Sometimes [17] My Heart's At Ease [17] The Apple of My Eye [17] Sheltered by the Stars, Cradled by the Moon, Covered by the Night [17] That's Where the South Begins [18] Since Won Long Hop Took One Long Hop to China [19] 1933

Down on the Delta: Fox Trot [2]You're Breakin' My Heart [2] Doin' What I Please [3] Tall Timber [3] A Handful of Keyas (Song) [3] Slower Than Molasses [3] Sittin' Up, Waitin' for You [3] Ain'tcha Glad? [3] On Sunday When We Gathered Around the Organ [3,15] 1934

Swing On, Mississippi [20]Clothes Line Ballet Dream Man Viper's Drag Russian Fantasy Effervescent Your Feet's Too Big Ace in the Hole [21] 1935

When Somebody Thinks You're Wonderful [22]The Panic Is On [23] Harlem Living Room Suite [11] Corn Whiskey Cocktail Functionizin' Scrimmage 1936

I Can See You All Over the Place [2]Shakin' It All Night Long [2] Wait and See [3] Stealin' Apples [3] Sugar Rose [24] 1937

Swingin' Hound (Charleston Hound) [1,2,6]Benny Sent Me [2] Lost Love [3] John Henry [3] The Joint is [was] Jumping [3,26] Our Love Was Meant To Be [15,25] 1938

I'm Savin' Up My PenniesUndercurrent I Got Love [2] What A Pretty Miss [2] I'm Gonna Fall In Love and Marry You [2] A Cottage in the Rain [2] Not There, Right Here [2] Bluer Than the Ocean Blues [2,33] I Had to Do It [3] Jealous of Me [3] Hopeless Love Affair [3] On Rainy Days [3] Patty Cake, Patty Cake [3,26] The Spider and The Fly, Poor Fly, Bye Bye [3,26] Hold My Hand [26] How Can I With You In My Heart [26] How Ya Baby? [26] I Can't Forgive You [26] If I Meant Something To You [26] Inside This Heart of Mine [26] Moonlight Mood [26] What Will I Do in the Morning? [26] What's Your Name? [26] Solid Eclipse [26] Yacht Club Swing [27] Swincopations Bach Up to Me Black Raspberry Jam Fractious Fingering Latch On Lounging at the Waldorf Paswonky 1939

AnitaHold Tight Smother Me With Your Love You Can't Have Your Cake and Eat It [2] Walkin' the Floor [3] Say Yes [3,26] Choo Choo [3,28] Honey Hush [29] 1940

Happy FeelingWinter Weather Old Grand Dad Original E Flat Blues [1] Mighty Fine [3] Stayin' At Home [3] London Suite Picadilly Chelsea Soho Bond Street Limehouse Whitechapel 1941

Oh, Baby, Sweet BabyI Repent All Nothin' To It (aka Gettin' Much Lately?) Rumpsteak Serenade You Must Be Losin' Your Mind Blue Velvet [2] Sad Sap Sucker Am I [29] Come and Get It [29] All That Meat and No Potatoes [29] Mamacita [30] Piano Antics China Jumps Sneakin' Home (or Sneakin' Around) Palm Garden Wan'rin' Around Falling Castle 1942

Up Jumped You With LoveYou Gotta Swing It Sing Out Fats Waller et le Swing Really Fine Breezin' (c.1942) The Jitterbug Waltz [3] We Need a Little Love [29] Cash for Your Trash [29] My Song of Hate [3] 1943

MartiniqueBouncin' on a V-Disc Swing Out to Victory Onion Time Moppin' and Boppin' [29,31] Early to Bed: Musical [32] A Girl Should Never Ripple When She Bends There's A Man [Gal] In My Life Me and my Old World Charm Supple Couple Slightly Less Than Wonderful This Is So Nice (It Must Be Illegal) Hi-De-Ho High in Harlem The Ladies Who Sing With the Band There's "Yes" In the Air Get Away Young Man Long Time, No Song Early to Bed On Your Mark When the Nylons Bloom Again c.1940s (Posth)

Look-A-HerePeek N' Seek Blues Idiom Paraphernalia The March of the Spades Boogie Woogie Suite Boogie Woogie Blues Boogie Woogie Stomp Boogie Woogie Rag Boogie Woogie Jump 1952/1953 (Posth)

An Armful of YouNever Heard of Such Stuff If You Can't Be Good, Be Careful [3] There'll Come a Time When You'll Need Me [11]

1. w/Clarence Williams

2. w/Spencer Williams 3. w/Andy Razaf 4. w/Harry Brooks 5. w/Joseph (Jo) Trent 6. w/Eddie Rector 7. w/Joe Jordan 8. w/Lester Santly 9. w/Stanley Adams 10. w/Thomas Morris 11. w/Irving Mills 12. w/Bud Allen 13. w/Jack Pettis 14. w/Harry Link 15. w/Alex Hill 16. w/Con Conrad 17. w/Joe Young 18. w/George Brown 19. w/Jack Meskill 20. w/Ned Washington 21. w/Frank Crumit & Bartley Costello 22. w/Harry Woods 23. w/George & Bert Clarke & Winston Tharp 24. w/Phil Ponce 25. w/Joe Davis 26. w/J.C. Johnson 27. w/Autrey & Johnson 28. w/Eugene Seebic 29. w/Ed Kirkeby 30. w/Anita Waller 31. w/Benny Carter 32. w/George Marion Jr. 33. w/Tommie Connor |

Rollography Rollography | |

|

1923

Got to Cool My Doggies NowLaughin' Cryin' Blues Your Time Now Snakes Hips Tain't Nobody's Biz-ness If I Do Papa Better Watch Your Step Haitian Blues Mama's Got the Blues Midnight Blues Last Go Round Blues 1924

You Can't Do What My Last Man DidThe Clearing House Blues Jail House Blues Do It Mr. So-and-So Don't Try to Take My Man Away A New Kind of Man With a New Kind of Love For Me 1926

Squeeze Me (A Boy in a Boat)18th Street Strut 1927

Cryin' for My Used To BeIf I Could Be With You [w/James P. Johnson] Nobody But My Baby (Is Getting My Love) I'm Coming Virginia 1928

Wild Cat Blues [Disputed as to Artist]1931

I'm Crazy 'Bout My Baby[w/J. Lawrence Cook] |

[QRS 2213] 05/1923 [QRS 2245] 05/1923 [QRS 2256] 06/1923 [QRS 2270] 06/1923 [QRS 2286] 07/1923 [QRS 2304] 08/1923 [QRS 2322] 08/1923 [QRS 2331] 08/1923 [QRS 2363] 09/1923 [QRS 2661] 06/1924 [QRS 2670] 06/1924 [QRS 2708] 06/1924 [QRS 2711] 06/1924 [Standard Play-a-Roll 0677] 08/1924 [QRS 3377] 03/1926 [QRS 3818] 03/1927 [QRS 3997] 08/1927 [QRS 4073] 11/1927 |

Although not a prominent figure of the ragtime era, Fats Waller eventually turned out to be a prominent figure in music in general. He embodied in so many ways the sheer joy of music, which for him was necessary to transcend his many personal struggles. Waller's overall success came from expansion of both ragtime formats and... well, himself. His sense of humor would certainly support such friendly jabs, but his life was not as easy going as his stage persona let on.

Early Years

Thomas Wright Waller was born to Edward Martin Waller and Adeline Lockett in New York City. He had two older brothers, Edward Lawson and William R., one older sister, Naomi, and one younger sister, Edith, the only five siblings of twelve who survived infancy. The 1900 census listed Robert (1894) and Alfred (1895), but they are found in no subsequent records and Adeline claims only four out of eleven children having survived as of 1910. While Waller at times mentioned his eleven brothers and sisters, it is clear that he sadly never even had the opportunity to meet some of them. It is also not clear if he knew his grandfather, Adolph Waller, who was a somewhat famous violinist in Virginia and the South.

The church was the primary focus of the household by the time he arrived, as Edward was a sometimes minister with the Abyssinian Baptist Church. The family had migrated from Virginia to New York City before Thomas was born in order to join that church, and followed when it moved from Greenwich Village to Harlem just after the turn of the 20th century. He was also involved with the Kings Chapel Assembly on E. 134th Street. Given this environment, it was natural that young Thomas was exposed to both traditional hymns as well as Negro spirituals and gospel. But he also soaked in the influences of secular music forms found throughout Harlem, and syncopation inevitably worked its way into his hymn playing, much to Edward's disapproval. His father even took the youth to a performance by pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski, but it seemed only to push him more towards syncopation. Edward's work with the church may not have paid the bills all that well, as the 1910 census shows Edward and his oldest son, Edward, working as truck drivers, and William as an office boy for an art gallery.

In later interviews Waller noted that his mother was very heavy, often weighing over 300 pounds, while his father was a mere 110 pounds (questionable, but still an indication that he was trim).

|

Thomas still studied classical piano and organ with the musical director of the church, Mrs. Edna Perrin, who made certain the boy learned the traditional organ works of Johann Sebastian Bach, an influence that would surface in later Waller compositions. He took additional piano instruction from Mrs. Alice Perry and Mrs. Frances Murphy. At ten years old Tom was able to play harmonium and organ proficiently. At Public School 89, he was deeply invested in the music program, learning to play the violin and upright bass quite proficiently, as well as playing piano with the school orchestra. In his early teens Waller attempted to pursue a musical career with some frustration. The family had moved to Lenox Avenue in Harlem in 1918, and Tom had left Wadley High School in order to work (some sources have cited DeWitt Clinton High School). He was helping to pay the bills and finance his continuing piano lessons.

It was after many visits to the local movie house, the integrated Lincoln Theater, and with some persistence that he ended up as their theater organist before he was even sixteen years old. There are reports, hard to validate, that they installed a $10,000 Wurlitzer organ just for him to play. It is more likely it was installed while he was in residence at the Lincoln. (The building is now the Metropolitan AME Church.) In order to increase his skill set with the complex instrument, Tom took lessons from Edward V. Thomas and German-born instructor Carl Bohn. In later interviews, Waller made sure it was known that both teachers were white. (Violinist Leopold Godowsky is also mentioned as a teacher during a stay by Thomas in Vienna, Austria, but a time line for that is difficult to confirm.) Performing was still a sideline even then, as he is listed as out of school and working for an upholstery company in the January 1920 census. His older brother was still working as a truck driver, and his mother, evidently growing more ill, had no position.

At that time the family was living at 44 East 133 Street in Harlem. One of the first tragedies in his life occurred that same year when his mother died soon after he turned sixteen.

|

Burying his sorrow in his music, Waller got a job as the organist playing a California=built Robert Morton theater model for the desegregated Lafayette Theater in Harlem in 1921 for $50 a week. He felt a need to escape his domineering father and soon left home, staying with friends in exchange for a sunny disposition and good entertainment at rent parties. The first of these was the home of Russell Brooks, where he had temporarily moved in order to escape his father. Brooks introduced Thomas to the music of James P. Johnson through Johnson's piano rolls. The teen, who was still tied to organ playing more than piano, tried to emulate Johnson's playing by learning from the rolls pumped one chord at a time. It turns out that fans of Johnson were also friends of Johnson, and through Brooks the thrilled youngster and the stride master soon met. Waller became a musical apprentice to Johnson from that point on, and would eventually overtake him in popularity and overall performance ability.

Development of Stride Style

As hard as it is to fathom, Johnson pinpointed Waller's biggest weakness as his left hand. Since Thomas had spent most of his musical life in front of an organ, he had developed a dependence on foot pedals for the lower notes that would normally be played by the left hand on the piano. This was soon overcome through diligence on the part of Johnson, and Waller's mighty strident left hand skills soon emerged. Jimmy managed to get him a job working at Leroy's Cabaret (cabarets having, in theory, replaced saloons during prohibition). By this time, Thomas was a hard-drinking bawdy diamond in the rough teen who was able to endear himself to nearly any audience, but had difficulty managing his own life, as others who attempted to do the same were able to attest to.

Jimmy managed to get him a job working at Leroy's Cabaret (cabarets having, in theory, replaced saloons during prohibition). By this time, Thomas was a hard-drinking bawdy diamond in the rough teen who was able to endear himself to nearly any audience, but had difficulty managing his own life, as others who attempted to do the same were able to attest to.

Jimmy managed to get him a job working at Leroy's Cabaret (cabarets having, in theory, replaced saloons during prohibition). By this time, Thomas was a hard-drinking bawdy diamond in the rough teen who was able to endear himself to nearly any audience, but had difficulty managing his own life, as others who attempted to do the same were able to attest to.

Jimmy managed to get him a job working at Leroy's Cabaret (cabarets having, in theory, replaced saloons during prohibition). By this time, Thomas was a hard-drinking bawdy diamond in the rough teen who was able to endear himself to nearly any audience, but had difficulty managing his own life, as others who attempted to do the same were able to attest to.Waller was first married to Edith Hatchet at 17 but soon was less than a full participant in that marriage, at least in practice. In spite of his ability to make money, his appetite for life and consumables in general left him constantly broke, although usually still in good humor as long as booze and ladies were available. His charming demeanor usually saw to that. The first major challenge to the marriage was when Thomas was offered a position with a touring vaudeville company, Liza and Her Shufflin' Six. Life on the road required less accountability, and afforded him an opportunity to grow in audience appeal as well as stature. They traveled at least one season on the aging black-run TOBA (Theater Owner's Booking Association) circuit.

In 1922, Edith gave birth to Thomas W. Waller Jr. A year later, the couple divorced. Thomas Sr., now nicknamed "Fats" due to his considerable height and girth, was starting to compose. He would continue to use Thomas professionally through the early 1930s for rolls, radio and recording sessions. His earliest recording sessions were arranged by composer Clarence Williams. He followed with some sides accompanying a young blues singer named Sarah Martin, then moved to QRS in 1923 thanks to the company's manager J. Lawrence Cook who utilized the teen's talents for a series of popular music piano rolls. Thomas Waller started appearing in QRS advertisements as early as mid-1923, albeit without photographs, as was the case with the other black QRS artists such as Jimmy Johnson, Clarence Johnson and Clarence Williams.

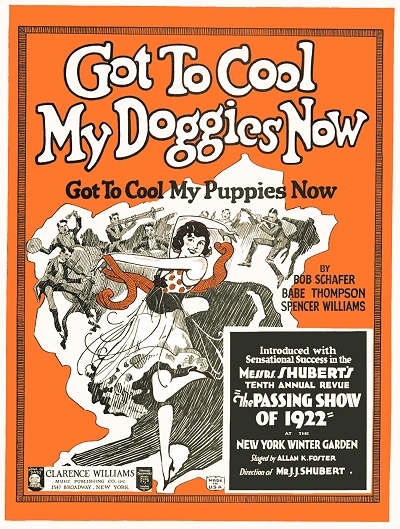

It was an interesting 1922 piece by Spencer Williams, originally titled Got to Cool My Puppies Now, but soon more widely known as Got to Cool My Doggies Now, that presented a mutual opportunity for both Spencer and Waller. It had been included in the Shubert's annual Passing Show of 1922, and within a few months it became one of the first piano rolls cut by Fats, along with a few other choice Williams numbers from the same year, including Snakes' Hips and Haitian Blues. Waller's exemplary interpretations rife with musical humor, held tenths and clever fills won him an instant friend and collaborator, and they would continue a fruitful and warm relationship through the end of Fats' all-too-short life. The 18-year-old was able to carve out a niche with his unique piano roll stylings, and later into a dynamic recording and radio career, often with Spencer right there with him. He likely helped Thomas get his first official recording session with OKeh Records in the spring of 1923, where he cut two fine early blues works, Birmingham Blues and Muscle Shoals Blues. While not fully developed as stride piano, these acoustically recorded sides certainly gave a glimpse of what was yet to come.

It had been included in the Shubert's annual Passing Show of 1922, and within a few months it became one of the first piano rolls cut by Fats, along with a few other choice Williams numbers from the same year, including Snakes' Hips and Haitian Blues. Waller's exemplary interpretations rife with musical humor, held tenths and clever fills won him an instant friend and collaborator, and they would continue a fruitful and warm relationship through the end of Fats' all-too-short life. The 18-year-old was able to carve out a niche with his unique piano roll stylings, and later into a dynamic recording and radio career, often with Spencer right there with him. He likely helped Thomas get his first official recording session with OKeh Records in the spring of 1923, where he cut two fine early blues works, Birmingham Blues and Muscle Shoals Blues. While not fully developed as stride piano, these acoustically recorded sides certainly gave a glimpse of what was yet to come.

It had been included in the Shubert's annual Passing Show of 1922, and within a few months it became one of the first piano rolls cut by Fats, along with a few other choice Williams numbers from the same year, including Snakes' Hips and Haitian Blues. Waller's exemplary interpretations rife with musical humor, held tenths and clever fills won him an instant friend and collaborator, and they would continue a fruitful and warm relationship through the end of Fats' all-too-short life. The 18-year-old was able to carve out a niche with his unique piano roll stylings, and later into a dynamic recording and radio career, often with Spencer right there with him. He likely helped Thomas get his first official recording session with OKeh Records in the spring of 1923, where he cut two fine early blues works, Birmingham Blues and Muscle Shoals Blues. While not fully developed as stride piano, these acoustically recorded sides certainly gave a glimpse of what was yet to come.

It had been included in the Shubert's annual Passing Show of 1922, and within a few months it became one of the first piano rolls cut by Fats, along with a few other choice Williams numbers from the same year, including Snakes' Hips and Haitian Blues. Waller's exemplary interpretations rife with musical humor, held tenths and clever fills won him an instant friend and collaborator, and they would continue a fruitful and warm relationship through the end of Fats' all-too-short life. The 18-year-old was able to carve out a niche with his unique piano roll stylings, and later into a dynamic recording and radio career, often with Spencer right there with him. He likely helped Thomas get his first official recording session with OKeh Records in the spring of 1923, where he cut two fine early blues works, Birmingham Blues and Muscle Shoals Blues. While not fully developed as stride piano, these acoustically recorded sides certainly gave a glimpse of what was yet to come.Around the same time as the piano rolls were being cut, and soon after his OKeh session, Thomas started doing live radio broadcasts on station WDT in Manhattan. One example from the July 30, 1923, Brooklyn Eagle shows him playing ten minutes at 12:10 p.m., the selections being Two A.M. Blues, Man, Man, Don't Do That To Me, and Don't Let Me Find You Here When I Get Back. Another from August 24 at 12:20 p.m. had him playing Farewell Blues and Mo'lasses. It is unclear if Fats had started singing on the radio at this time, conveying his ebullient personality across the airwaves, but that more likely came later on. In 1924 he was spotted doing 30 minute spots on WGCP with pianist Roy Banks.

In most of his songs, starting in the early 1920s, Waller did not do too much lyrically, although some of the words he wrote were rather bawdy in nature. For example, many know Squeeze Me as a gentle ballad. However the original melody had ribald lyrics along the lines of, "Have you ever seen the boy in the boat, he doesn't wear a hat or a coat," which is rife with lewd sexual references. They were great for rent parties but had to be refined or replaced for the purpose of piano song rolls. Along with new lyrics by Clarence Williams, and taking no credit himself, a reworking of the melody by Spencer Williams, the song emerged as Squeeze Me and became another enduring Waller success on stage and on record and roll.

For example, many know Squeeze Me as a gentle ballad. However the original melody had ribald lyrics along the lines of, "Have you ever seen the boy in the boat, he doesn't wear a hat or a coat," which is rife with lewd sexual references. They were great for rent parties but had to be refined or replaced for the purpose of piano song rolls. Along with new lyrics by Clarence Williams, and taking no credit himself, a reworking of the melody by Spencer Williams, the song emerged as Squeeze Me and became another enduring Waller success on stage and on record and roll.

For example, many know Squeeze Me as a gentle ballad. However the original melody had ribald lyrics along the lines of, "Have you ever seen the boy in the boat, he doesn't wear a hat or a coat," which is rife with lewd sexual references. They were great for rent parties but had to be refined or replaced for the purpose of piano song rolls. Along with new lyrics by Clarence Williams, and taking no credit himself, a reworking of the melody by Spencer Williams, the song emerged as Squeeze Me and became another enduring Waller success on stage and on record and roll.

For example, many know Squeeze Me as a gentle ballad. However the original melody had ribald lyrics along the lines of, "Have you ever seen the boy in the boat, he doesn't wear a hat or a coat," which is rife with lewd sexual references. They were great for rent parties but had to be refined or replaced for the purpose of piano song rolls. Along with new lyrics by Clarence Williams, and taking no credit himself, a reworking of the melody by Spencer Williams, the song emerged as Squeeze Me and became another enduring Waller success on stage and on record and roll.The talented lyricists he hooked up with early on in his composing career helped to further refine his talents be presenting him with appropriate lyrics to compose to, or in the case of some of his earlier songs, fit better lyrics to them, as they had to for the roll of Squeeze Me. Among those talents were blues publishers Clarence Williams, and lyricists Jo Trent and Andy Razaf (birth name Andrea Menentania Razafinkeriefo). In 1924, Spencer Williams, after having written padded his own catalog with blues of every kind, such as Chain Gang Blues, Poor House Blues, Tombstone Blues, Western Union Blues, and many more, sat down with Waller and went even deeper into the world of blues by composing pieces that may never have been published, but were at least copyrighted and probably performed at some point. These included Bloody Razor Blues, Bullet Wound Blues, and Ramblin' Papa Blues. One of the most whimsical titles they came up was Flat Tire Papa, Mama's Gonna Give You Air, a phrase which undoubtedly raised eyebrows and conjured up a number of profane images. Just the same, Waller would end up composing most of his best works with Razaf, but both would usually be equally destitute as a result of bad business decisions concerning their music and lyrics. Waller and Razaf were first seen working together as a piano and vocal team on radio WGCP in 1925, with Razaf billed as "The Yodeling Kid."

Waller and Razaf were first seen working together as a piano and vocal team on radio WGCP in 1925, with Razaf billed as "The Yodeling Kid."

Waller and Razaf were first seen working together as a piano and vocal team on radio WGCP in 1925, with Razaf billed as "The Yodeling Kid."

Waller and Razaf were first seen working together as a piano and vocal team on radio WGCP in 1925, with Razaf billed as "The Yodeling Kid."Throughout the 1920s Waller and company composed a number of lesser blues pieces and songs that either saw publication or were committed to piano roll. Many of his pieces composed in 1924 and 1925 with a variety of lyricists remained unpublished for decades, and some never even recorded, so prolific were his melodies. It was clear on both the early recordings and even the piano rolls that Waller's touch had a wide range and his chord choices and execution were revolutionary for their time. His sense of timing, and even how long to hold notes, was studied by many up and coming Harlem pianists through both rolls and records. Yet he was still constantly broke.

As a result of his financial woes, some of his earlier songs or piano rolls were sold hastily and anonymously, so some have been lost to us through obscurity. Publishers routinely bought songs outright for low prices, claiming that they couldn't be sure of sales potential that early on. A few pieces from this era have been attributed to him based on remembrances of his peers and colleagues. One of those was legendary stride pianist Willie "The Lion" Smith, who gave Thomas the nickname "Filthy." Smith's preference for late 19th Century impressionistic composers influenced Waller's use of classical pianistic devices in many of his solo compositions and performances. Some of his peers, and indeed mentions in newspaper interviews, claim that he may have composed the melodies for such songs as On the Sunny Side of the Street or I Can't Give You Anything but Love, pieces attributed to him largely through performance.

One probable incident happened before he reached his wider fame. It was in Chicago in 1926 when Waller was working on a regular basis with bandleader Erskine Tate. He was leaving a performance when he was reportedly "kidnapped" at gunpoint by four men who subsequently delivered him to the Hawthorne Inn, a hangout of the notorious gangster "Scarface" Al Capone. Fats was led inside in the midst of a raucous party, then pushed to a piano and ordered to play with guns pointed at him.

As it turns out, he was a "surprise guest" for the mobster's birthday party, and he knew as long as he played ball - or piano - he would likely live through the event. Rumor has it that it lasted for three days, but given Waller's occasional propensity for stretching actual circumstances, it is hard to confirm this as fact. Just the same, he evidently left drunk but much richer due to thousands of dollars in tips. It was also around this time that he met and married his second wife, Anita Rutherford. They would eventually have two sons, Maurice and Ronald.

|

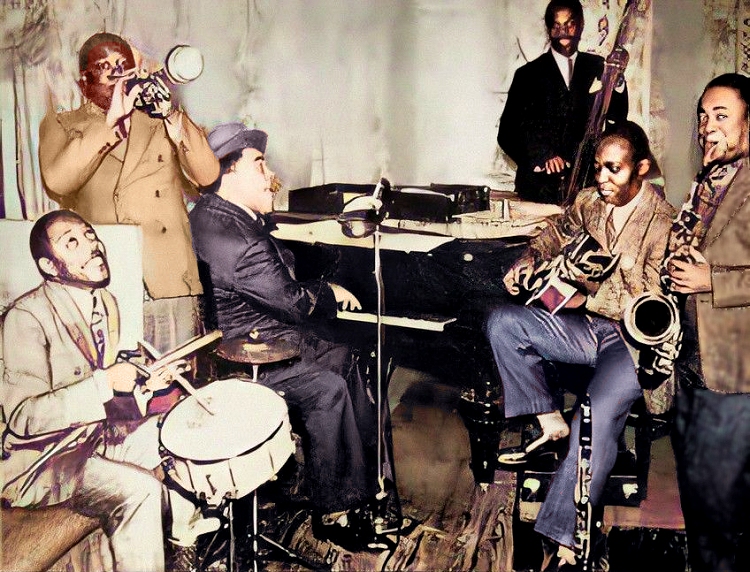

Waller started recording for Victor Records in 1926, turning out passable sides of his own tunes as well as some popular ones of the day. Many of these were done on their custom Estey organ, including the tune Sugar, which was sung in fine style by Alberta Hunter. This was a challenge that many artists did not enjoy, given that the organ and the sounding pipes were in separate chambers, and there was a delay between pressing the keys and the sound production. However, Thomas managed to find his own percussive style that allowed him to also record some organ tracks with small ensembles. He kept the songs coming, writing with Razaf, Trent and Thomas Morris, but most of them that were not committed to piano roll were being recorded by others. One good example was his Alligator Crawl (originally House Party Stomp then Charleston Stomp) of 1927 which was recorded by no less than Louis Armstrong, became a popular piano roll, and, later, a sheet music number with lyrics added. Yet he would not record it for another seven years. In 1927 he recorded a number of hot pipe organ tracks with a group led by cornetist Thomas Morris. The tracks with Morris' Hot Babies were cut by Victor either on their studio Estey, or in a Camden, New Jersey church in May and December, and are quite predictive of the swinging style that Waller would soon bring to his piano tracks.

After recording less than two dozen fine piano rolls, Waller found himself too much in demand to continue this practice and no rolls that can be definitively identified as played by him appeared after 1927. Cook managed to supply the roll market with a number of fine cuts over the next fifteen years that were highly imitative of Waller, many pulled from his subsequent recorded tracks. Waller himself spent much of 1927 through mid-1928 on the road in vaudeville, and briefly with a stage show.

The Rise to Fame

Even before he had made waves with the general public, Waller appeared in Carnegie hall for the first time just over a month before his 24th birthday. In 1927, his mentor and champion, Jimmy Johnson, had compiled/composed a major symphonic work, Yamekraw - A Negro Rhapsody, a mix of spirituals and folk pieces. It was named after a black community in Savannah, Georgia. In April 1928, W.C. Handy hosted a concert at Carnegie Hall in Manhattan which included Johnson and his new work. According to The Music Trade Review of May 12, 1928: "W.C. Handy, pioneer composer of many varieties of 'blues' and author of several books on the subject, gave a successful concert in Carnegie Hall, New York, recently, assisted by an orchestra and a group of Jubilee Singers.

The program included a negro [sic] rhapsody entitled 'Yamecraw,' [sic - Yamekraw] composed by James P. Johnson, in which Thomas Waller played the piano solos." A two piano presentation had been planned, but Johnson had a contractual obligation elsewhere that evening, so Waller had to wing it on his own.

|

Fats got involved with a 1928 production called Keep Shufflin' in which he contributed some pieces to and played in the pit orchestra conducted by Johnson. He left that show for a solo gig at the organ playing at the Royal Theatre in Philadelphia during June and July. Having been ordered by the courts in 1926 by pay $35 per week in child support to Edith and son Thomas Jr., failure to do so for much of that two year period resulted in a prison stay. According to the Afro American of September 15, 1928 (around three weeks after the sentence was pronounced), his failure to pay "has landed Fats Waller, popular blues writer, behind the bars to serve a term of from 6 months to 3 years, in the county penitentiary." His stay was ultimately less than five months.

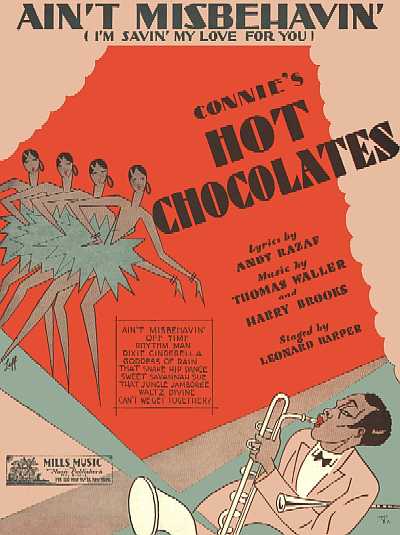

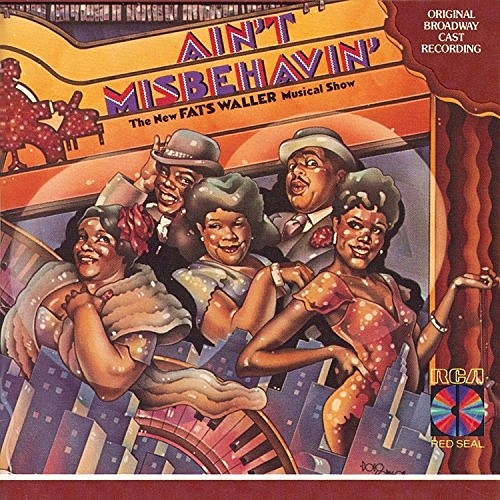

After he was released in mid-December, Fats was lured back to the stage to assist with another show in early 1929, this time hosted by the notorious Connie's Inn in Harlem, right next to the Lafayette Theater in Harlem, which was owned and operated by New York gangsters, the most notable of them being brothers Connie and George Immerman and Dutch Schultz. The show was Connie's Hot Chocolates starring the "Hi-De-Ho Man", singer Cab Calloway, with lyrics by Andy Razaf and Harry Brooks. It featured a boy/girl number titled Ain't Misbehavin' which was an instant hit and recorded almost immediately, including one memorably hot session by a member of the original stage band, Louis Armstrong. The song was so popular that the pit band had to play extended encores of it during the intermission. Another hit for the duo was Black and Blue, a thinly veiled criticism of the racist treatment of blacks by his white benefactors and the white population in general. Unfortunately all of the songs from the musical, which played for over 200 performances from June through December, were sold to Mills Music for a paltry $500, which Waller could soon have made every day from royalties had he held on to them.

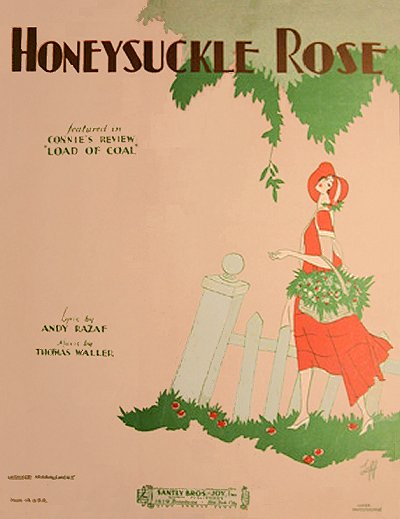

The writer's insistent hosts, who the composers had trouble refusing, asked for more, and the team turned out Load of Coal Some chronologies suggest that Load of Coal may have actually been staged before Connie's Hot Chocolates given contemporary accounts of the various collaborations. The bulk of the song list of Load of Coal has been largely lost to history, making that chronology hard to confirm. Just the same, the featured tune of that show was Honeysuckle Rose, a song that Fats would play almost daily during the last decade of his life. In fact, nine years Honeysuckle Rose reached immortal status with an 18 minute rendition played and recorded at Carnegie Hall by the Benny Goodman orchestra featuring Count Basie at the piano.

Ultimately, it was an amazing recording session on March 1, 1929, at Victor in Camden, New Jersey, that yielded a landmark stride piano rag, A Handful of Keys, the nicely understated Numb Fumblin', The Minor Drag and Harlem Fuss. Guitarist Eddie Condon, who played on the latter two tunes as part of Fats Waller and His Buddies, had been tasked the day before with making sure that Waller showed up at the recording session on time, which required shadowing him throughout a busy night. They got up with only two hours to go, and Waller started calling whoever he could find to join him. They did make it on time, and Waller instructed the ensemble in the two improvised tunes. When Minor Drag and Harlem Fuss were initially released the labels were reversed causing some confusion among other musicians. They have since been correctly identified in compilations.

By the end of the landmark year of 1929, with several more recordings to his credit, including Ain't Misbehavin', Honeysuckle Rose, Gladyse and Smashing Thirds, Waller had proven himself as viable popular pianist and was on his way. An even better prospect for his career was that he did not have to be cast as a race pianist on radio or elsewhere, yet his image was no longer hidden from view. Many of his sides from that point on were featured on the mainstream Victor label or their secondary Bluebird label, yet he would not have a full contract with Victor for another five years.

The fame brought by Ain't Misbehavin' and Honeysuckle Rose, plus other assorted pieces well known to Tin Pan Alley publishers by this time, also favored Waller in a rather mysterious way. It has been noted that some days when he and Razaf needed some extra dough that they would write a song, make several copies, then walk it around 42nd to 46th Street where most of the publishers were situated, sometimes selling it to several of them in a day. Many of them bought it simply because it was a Waller tune, and they ended up sorting out the legal issues later, usually forgiving the entrepreneurial zeal of the composer.

By 1930 Ain't Misbehavin' had become a popular national hit. In an interview with William I. Gibson of the Afro American of February 8, 1930, Fats revealed the inspiration for the piece:

Pianist-Organist, only 25, Called "Rachmaninoff of Jazz," finds Inspiration for Songs in Commonplace Happenings... 300,000 copies of "Ain't Misbehavin'" Sold.

"Say Boy, you goin' to that dance tonight?"

"Ain't misbehavin', poducer, ain't misbehavin'."

The scene was Gary, Indiana, during the summer of 1928, and the characters in this little snatch of conversation were just two of the town's roustabouts.

Thomas (Fats) Waller, styled today as "the Rachmaninoff of Jazz," spending a few days in the Hoosier city, heard it. And as he rambled about the town, he heard this bit of slang again and again. "Some day," says "Fats" to himself, "I'm going to write a piece around that bit of slang." And for a while he forgot that he ever heard it.

Back in New York, however, the memory of the phrase seemed to haunt him, so much so, that four days before Christmas, 1928, the rotund ivory tickler sat down and made a rough draft of the song. He called in Andy Razaf the lyric writer, and in four days the pair had completed the song.

But like the line in the song, they kept it "on the shelf" until February 1929. One day when Connie Immerman was head over heels with plans to put his floor show on Broadway as "Hot Chocolates," "Fats," who was working at Connie's Inn then, took the piece to him and played it over.

The voluble Connie threw up his hands in despair. "Take it away," he cried, "I can't us it."

But "Fats" was not so easily discouraged. He called in Andy and the two insisted that Connie hear the number again. After much persuasion the producer decided to give the piece a trial. What has happened since is familiar history to most of us who have either heard the number in "Hot Chocolates," over the radio, on phonograph records or otherwise. Today the sales have passed the 3000,000 mark...

With Andy Razaf, "Fats" is the composer of "My Fate Is In Your Hands," which, by the way, has passed the 750,000 mark since it came out in November. "The way that piece got its name is funny," said the genial pianist-organist as he reminisced a while. "Andy Razaf, Al Poindexter, violinist, and myself were speeding through Asbury Park on our way to Bradley Beach about 1:30 on morning when a constable stopped us.

"He soaked a $50 fine on us, and the three of us did not have the necessary dough. Razaf said, 'Give me a break, Mr. Constable. My fate is in your hands, you know.' And whether it was those words or not, the constable softened and accepted the money we had, about $24, in payment of the fine.

"The next day, Andy, reciting the incident, sad, 'Fats, let's write a piece with the title "My Fate is in Your Hands".' We did and you know the rest."

The next few years found Waller doing nearly any job for money. He and Razaf often performed on the road when not at Connie's, with both of them singing their songs on stage. Along with Razaf, Waller started writing with fellow stride pianist and bandleader Alex Hill, who has also cut some extraordinary solos in 1929. In early 1931 they turned out another great Waller hit, I'm Crazy 'Bout My Baby. Hill also wrote tunes with Razaf, but went on to a short-lived career as an orchestra leader and arranger, dying in early 1937.

Thomas occasionally wrote songs for musicals, or his songs were interpolated into revues. While he and Razaf together with Spencer Williams were still contributing songs to Connie Immerman's shows, by 1931 they were no longer participating in them on a regular basis, except for a brief period when Waller took over orchestra duties from composer/arranger Fletcher Henderson.

In 1932 Connie Immerman wrote to the Afro American noting that he was opening a new downtown office in order to find and cultivate "colored talent for the amusement of New York City's elite." Waller, Razaf and Jimmy Johnson were mentioned as still being staff composers for his organization.

|

In the late summer of 1932 Spencer William, who had spent nearly three years in France and Europe with Josephine Baker from 1925 to 1928, wanted to return to his favored city of Paris, this time bringing Waller in tow. Having recently contributed a show to Connie's Inn with the help of Andy Razaf, the two were in tune with each other as collaborators. In order to gain passage, they reportedly locked themselves in Spencer's apartment for a weekend and turned out 27 songs, of which only a handful were published and none were worthy of hit status. However, with their names attached, the songs quickly sold, and the boys boarded the Ille de France for Le Havre. Both were immediately well-received, and Spencer went back to his old haunts and played at some new ones throughout August. The lure of not only diminished racial discrimination, but of free-flowing alcohol, which was still "prohibited" in the U.S., was undeniable to Spencer and many of his fellow American musicians. One of the new locations in which he performed was Bricktop's latest venture, her Monico nightclub at 66 Rue Pigalle. Waller made a splash as well, and both were remembered some decades later by French pianist Alain Romains in an interview:

Spencer had a big round face like sunshine. He was always smiling and had a little cigar. He and Fats were very funny people. They used to call us white musicians "ofays" and they called themselves "spade." And when they didn't want us to know what they were talking about they would use jive. … A lot of the white musicians—Americans—wouldn't play with them. They recognized that they were good musicians, but they wouldn't play with them.

After less than a month, Waller longed for home, a worry exacerbated by his not having a confirmed return ticket. So one late August evening, as later recalled by Williams, Fats simply disappeared from the café they were in and abandoned France without a word, returning to New York on the Paris. While he was rumored as being destined also for London, England, to record for HMB records there, he ended up returning to New York directly. Fats would eventually return to Europe and finally get to London, but there was still work to do at home.

Radio, Records and Film

Upon his return Waller once again hit the American airwaves, although this time from Cincinnati, Ohio.Station WLW was one of the most powerful radio stations in the eastern part of the United States, run by the Crosley Radio Corporation.

Owners Powell and Lewis Crosley also manufactured radios and, for a brief period, automobiles and major home appliances. At one point in the mid-1930s they boosted their power so much that they were causing interference with Canadian stations and received mail from Europe. In order to increase their on-air visibility and therefore their advertiser base, the management sought out the best possible entertainment. Fats had hired Phil Ponce as his manager, and Ponce in turn got Waller his own show on WLW. So the pianist briefly took up residence in Cincinnati. Fat's Waller's Rhythm Club not only featured his playing, but a vocal group called The Southern Suns as well as white studio band, making this a landmark mixed race broadcast. The show remained on the air from November 1932 until January 1934, with brief interruptions so Waller could fulfill other engagements. In the interim, as it was received for free by listeners from the Deep South to southern Canada and New York to Omaha, Nebraska, it made Waller an even more popular personality, again transcending racial barriers through his affable and laughable good nature.

|

Waller did not leave WLW under favorable circumstances. While his show garnered excellent ratings and high listenership, they let him go with the unofficial story being that he drank too much in the studio and was leaving gin bottles scattered about. While this seems plausible, even though many similar concerns put up with such behavior from popular musicians, there was a more likely reason revealed by a friend of Lewis Crosley. It appears that Waller was either attempting to or successfully engaged with a white female secretary at the station, and the owners of the nearly all-white company found this to be unacceptable. For Waller this was merely a bump in the road as he had no trouble finding other radio work nearly immediately.

It appears that Waller was either attempting to or successfully engaged with a white female secretary at the station, and the owners of the nearly all-white company found this to be unacceptable. For Waller this was merely a bump in the road as he had no trouble finding other radio work nearly immediately.

It appears that Waller was either attempting to or successfully engaged with a white female secretary at the station, and the owners of the nearly all-white company found this to be unacceptable. For Waller this was merely a bump in the road as he had no trouble finding other radio work nearly immediately.

It appears that Waller was either attempting to or successfully engaged with a white female secretary at the station, and the owners of the nearly all-white company found this to be unacceptable. For Waller this was merely a bump in the road as he had no trouble finding other radio work nearly immediately.Fats turned out a large number of fabulous recordings for RCA Victor with a fairly consistent frequency. Many times he would find music waiting for him in the studio, and after a couple of read throughs and a rehearsal would knock out another classic by Carmichael or Kalmar and Ruby or whatever the flavor of the month was, creating an indelible imprint on acetate. This is how many classics like Stardust and Old Rocking Chair found their way into the hearts of other jazz musicians and listeners. The same was true of his increasingly frequent radio broadcasts, which feature a mix of his vocals or those of Andy's with a fair smattering of his dynamic piano solos.

It was the recordings of his own pieces, such as Alligator Crawl and Valentine Stomp, that made the biggest impact on the buying public. In November 1934, on the same day he finally signed a new (non-exclusive) long-term contract with Victor, Fats cut an incredible set of solo piano tracks. They included an earlier composition, Alligator Crawl, the somewhat risqué Viper's Drag, and his experimental Clothesline Ballet and African Ripples. These solos in particular highlighted the technical skill of Waller's playing and composition that was often lost beneath the humor he presented on stage or his new best love, radio.

Four months later he would lay down another fine set of tracks for The Associated Programming Service, an ancestor of the Muzak Company, which provided custom discs for controlled environments such as offices. These included his Russian Fantasy and the somewhat improvised E-Flat Blues.

|

Fats Waller and radio were a perfect combination, as his humorous asides and lyrical alterations were both hip and smarmy, creating a multi-ethnic audience that simply enjoyed good music and tawdry humor. It was during his early radio days that Waller began to gain a reputation for his vocal performances of popular tunes. Many great sessions were heard with Fats and his Rhythm from the mid-1930s through the early 1940s, most recorded for posterity. The first sessions of this group were also in 1934 for Victor. Most times the group was assembled at the last notice, and they would record as many as ten different tracks in a day, rarely knowing in advance what the pieces would be. From that point on he did less piano solo work, preferring to record with ensembles.

Waller's songs had already been featured in films, particularly I've Got A Feeling I'm Falling composed with Billy Rose and sung by his wife at the time Fannie Brice. Yet it was not until 1935 that Waller himself would appear on screen. Hooray For Love (originally titled Four Stars for Love) was a familiar plot to Waller, dealing with the behind the scenes trauma and drama of stage musicals with financial woes and gangsters, etc. He was one of a number of artists who essentially did cameo work in this film, among them being Bill "Bojangles" Robinson. One extended sequence featuring Harlem musicians was excised before the release, a disappointment to Waller and his peers. But they were still up there in a feature motion picture. One scene with Bojangles and Fats performing Livin' in a Great Big Way was memorable enough that many caricatures of the two, Waller in particular, appeared in cartoons of the late 1930s through early 1940s.

While Tom was down in Hollywood for the filming his agent took advantage of the untapped coast and booked him in several places around Los Angeles. In April, 1935, he and singer Pinky Tomlin were featured at the Paramount Theater, and both got glowing reviews in the Los Angeles Times of April 12:

|

Two gentlemen of widely different extraction stole most of the glory on the Paramount's new bill... One was Pinky Tomlin known as "The Oklahoma Flash" and "the hog-callin' crooner"... The other was Thomas (Fats) Waller, a short, [at 5'11" this was not the case] squat Negro with a pale complexion, a cream-colored bowler and a touch like dapple sunlight at the keyboard...

The audience was on tenterhooks, waiting first for Pinky and then Fats...

Fats talk-sings at the piano. He skimmed through "Honeysuckle Rose," which he wrote, and "St. Louis Blues," which he didn't. Also, "Believe it, Beloved." And man! is he good. Missing was the orchestra with which he used to bat out the fastest "scat" music on the air. Rube Wolf substituted.

Later in the year he would go back to the East Coast doing a tour with the Columbia Broadcasting Orchestra, the group he had been playing with since leaving WLW and moving to the CBS network in New York. While he was in Philadelphia in May to perform at the Lincoln Theater, Fats ended up gaining a bit of a victory over some hoodlums who had taken to extracting, or extorting funds from black musicians. As reported in Philadelphia newspapers and the Afro-American, he had been approached by members of a gang offering "protection" from theft by the South Street and Fifteenth Street gangs on the night he drew his earnings. [Note that a decade later comedian Bill Cosby would grow up in the same area, and he sometimes mentioned such gangs in his remembrances.] Refusing their services, Waller was threatened by the chief of the gang, saying the "something would happen if he was not able to be seen" the next night after the payroll draw. The Department of Justice, CBS and the Philadelphia Police Department assigned a Federal guard detail to Waller. The threat was very credible as the gangs had already successfully extorted money from Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway. In the end, gang members were arrested and Fats left Philadelphia unscathed, but also unnerved.

The 1935 tour continued on through Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia, then to Boston and New England before the "Harmful Little Armful" and his group got back to New York City in the fall, and back to radio and recordings. Then Hollywood called again. Hooray for Love was followed by an appearance in King of Burlesque, filmed in late 1935 and released in January 1936, in which he sings I've Got My Fingers Crossed. As was a common practice with some film studios of the time, his segment was incidental to the plot, so could be excised for exhibition in the South where integration in films did not sell tickets. A bonus, however, was that the same excised portion could be used as a short subject in areas with high black populations, bringing in even more revenue when advertised.

Losing, then Finding Himself Again

Between radio and recording gigs, Waller and his combo spent quite a bit of 1936 and 1937 on the road. It was there that he could connect directly with a new audience every night, and more or less be himself with few constraints, at least when he was not performing in the Deep South. A lot of the studio work, and even some on radio, was driven by publishers who wanted him to promote their songs.

However, to some of his friends he seemed to be increasingly lost, and at times out of control. Fans complained when he would not autograph photos. Columnists wrote that his performances with a glass of bourbon prominent at the piano were perhaps diminished by the booze. Just the same, radio commentator Walter Winchell named Waller as the true "King of Swing" in February 1938, as factions for Benny Goodman and Louis Armstrong were trying to also claim that title. But behind the scenes was a man who wanted to be recognized for his pianistic and writing skills more than for his humorous renditions of Tin Pan Alley pieces and vocal non-sequiturs.

|

This was partially realized after his continuous period of road trips and broadcasts, when he finally decided to take a break and do something different - or at least go somewhere different. In early 1938 his new manager and sometimes collaborator Ed Kirkeby, a white entrepreneur, took over from Ponce under friendly circumstances. With little urging necessary from Kirkeby, he and Waller sailed for Europe in mid-1938. This first trip focused largely on the United Kingdom with additional stops in Denmark, Norway and Sweden. He found a very receptive and less judgmental audience in England. Some of his travels on this trip included his old colleague Spencer Williams, with whom he frequented the London night spots. The two wrote a number of songs together which were taken back to New York for publication, including the lovely A Cottage in the Rain. Waller also made a few recordings, including another Williams song, All Pent Up in a Pent House. This was part of a series done on pipe organ at St. George's Hall and the HMV Abbey Road studio in late August, some with other instrumentalists accompanying him. On that trip he was also featured on a very early BBC television broadcast.

Back in the United States, Fats set up shop for a delightful and refreshing run of broadcasts from the newly relocated Yacht Club on 52nd Street in Manhattan. Reunited with many of his band mates, his group included Eugene Cedric (ts/cl), Herman Autrey (tpt), Al Casey (gt), Cedric Wallace (bs) and Slick Jones (dr). From October through the middle of January 1939 they made a splash in midtown Manhattan, and a good number of fine surviving recorded transcriptions to boot. During that run, on November, 1938, Waller was nearly killed in a scuffle that involved his brother Eddie. The incident, which underscored many of the racial issues Waller encountered both at home and on tour, was reported on in several U.S. papers, including The Afro American:

|

Fats Waller, pianist, singer and maestro, missed death early Sunday morning when an angered white man fired at him outside the Turf Club.

The bullet hit his brother, Edward Lawson Waller... the latter is at Harlem Hospital in a serious condition.

Police arrested Thomas Kehoe, white... for the shooting. Fats and his brother were in the Turf Club on Saturday night. Two white girls were there and one of them approached Fats for an autograph. The [orchestra] leader complied. Kehoe, watching the scene, gained the impression that the Waller brothers were "dating" the girls.

About 4 a.m. the two Wallers left the Turf Club... While they were getting into a taxicab the brothers noticed that Kehoe was trying to beat the two white girls, who had also just left the club. With the Wallers was Bobby Driver, Fats Waller's chauffeur and aide.

Fats stopped to tell the white man that he should be ashamed to strike two defenseless women. A minute or so later as the three were preparing to drive off Kehoe left the girls, rushed up to the cab, opened the door and fired at Fats. Instead he shot Eddie. The bullets struck him in the left leg and right hip.

Kehoe, who is a longshoreman, was injured internally and his skull was fractured in the resulting melee, as club patrons rushed to the aid of the Wallers. His condition is serious. Police said he was on parole on charges of robbery and carrying a gun. The two white girls fled and were not located.

This incident shook Tom a bit, but he kept plugging away. In January it was announced that he would again be setting sail for Europe, this time for a much longer tour. Waller was so entranced by the experiences he had in London that he wrote his London Suite, each movement named for a different part of the town. It was recorded with other pieces on the organ during his return visit to England in June 1939. Traveling along with fellow performer, trumpeter Jimmie Lunceford, who he had worked with on several occasions, Waller and Lunceford also revisited Norway and stopped in Scandinavia, finding the same warm reception everywhere. He also hung out with Spencer for one last round in London. Fats also went back to Paris where he was invited to play the pipe organ at the Notre Dame Cathedral, something he considered to be one of the greatest honors of his brief life. Given the deteriorating situation on the continent, Waller would never again be able to return as he died before the end of World War II.

After this tour he went to Chicago in August and at the invitation of musical entrepreneur John Hammond gave a boost to three boogie-woogie pianists, appearing with them in concert. While they would never eclipse Waller's fame, Albert Ammons, Meade"Lux" Lewis and Pete Johnson would signal a change in direction for blues piano playing into the next decade. It is interesting to note that his professional contract and rider had a very clear clause in them that barred the association of his name with the term "boogie-woogie." Yet after his death a suite of his own boogie-woogie pieces was issued.

Professional Struggles and A Difficult Ending

As the swing era moved forward under the capable hands of Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey, and Waller's old friend Fletcher Henderson, Fats had to adapt or go under, as many other musicians already had. His long-time friend Jimmy Johnson had suffered a couple of strokes around 1939 to 1940, and they diminished his playing ability for a while. His older brother Robert died in later February, 1940, compounding his woes. In the 1940 census taken in Queens in April, Thomas was still residing with Anita, Maurice and Ronald, plus his mother-in-law and a servant. He listed himself as a musician in the entertainment industry.

In this new decade, Waller now had to compete with the likes of Art Tatum and Teddy Wilson, both formidable jazz pianists.

While he was able to adapt and adopt swing in his act, it was starting to look old to many of his fans. He once again found himself needing to work with bands to help with the swing style, and counting even more on his personality to set him apart from other acts of the day. He assembled an orchestra of 15 first rate performers and took them out West in 1940 for a new tour.

|

In 1941 Waller shot a number of short films or "soundies," which in a more contemporary parlance would be the equivalent of "music videos," except without the video media. These featured Fats doing his very best material in a high class setting. Directed by Warren Murray, they included Ain't Misbehavin', Honeysuckle Rose, Your Feet's Too Big, and This Joint is Jumpin', the last one being released in 1942. A medley of this material was also shot and assembled, minus This Joint is Jumpin', but did not appear until 1945 after his death. While he was filming those, Fats appeared at the famous Cocoanut Grove in Los Angeles to a rousing reception.

This was not quite the case, at least with the critics, after his solo concert at the prestigious Carnegie Hall on January 14, 1942. Fats had been preceded in the fabled space by a number of notable jazz performances ranging from Benny Goodman to the best of Harlem pianists, including Handy and Johnson. But this evening was all about him, even though there were a number of fine guest performers joining the maestro on stage. The end result of that evening has remained a questionable point of controversy ever since, with a number of potential reasons put forward as to how Waller came off in that space. The initial review in the New York Times of January 15 was indicative of what some of the audience may have felt:

Thomas (Fats) Waller, who has contributed mightily to American jazz as a pianist, singer, composer, personality and band leader, last night gave a solo recital at Carnegie Hall.

The news is bad. The program, according to a note by John Hammond, was dedicated to Fats's artistry as a musician and composer, and the pianist apparently took this seriously. Instead of being his buoyant, rhythm-pounding self, he improvised soulfully, for long stretches at a time, first on the piano and then on the Hammond electric organ. Long pauses between his groups did not help matter.

There was a near-capacity audience of 2,600 which was more than ready to be pleased. It applauded when a recognizable melody emerged in the rambling improvisations. It even began to "get hep" when Fats started his improvisation on eight bars from Elgar's "Pomp and Circumstance" on the organ. But Fats stopped playing with a swinging rhythmic bass, and went off into fancy ornamental figures again and the audience relapsed.

Half an hour later when he started playing in jazz style again during "I'm Gonna Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter," the audience started beating its feet and tapping its palms to get him started. But to no avail. After a twenty-three minute intermission the audience just sat numbly through a long "London Suite" and the succeeding variations on a Tchaikovsky Theme which was indistinguishable from the suite.

Even the final reunion of the celebrated Chicagoans was disappointing, for the program had gone on so long that they only had time for two numbers. The combined talents of Gene Krupa, Eddie Condon, Bud Freeman, Pee Wee Russell, Max Kaminsky and John Kirby could not save the evening.

|

Just the same, in spite of those trials, Waller did his patriotic duty for his country in the troops during the early part of World War II. His considerable weight, and perhaps his import as a performer who would be good for morale, kept him from having to register for the draft in 1942. However, he not only wrote pieces supporting the war effort and the sale of bonds, and even the collection of personal items for recycling (Cash for Your Trash), Waller recorded some very unique tracks on a series of highly acclaimed V-Discs (Victory Discs) intended for overseas broadcasts. Since these were large transcription discs that allowed him some flexibility in terms of recording time, he went after these with some level of zeal, revealing improvisations and variations not previously laid down.

Hollywood called once again in early 1943 for the 20th Century Fox production of the all-black film Stormy Weather. Virtually every black musician dealing in nostalgic music that was available or willing was hired for the film, including Bill Robinson, Cab Calloway, Ada Brown, the dancing Nicholas Brothers and Waller, playing themselves for the most part, albeit with Robinson using a different name.

The main feature was singer Lena Horne who did a magnificent job with the title track. However, much of the attention went to the pair of tunes rendered by Fats in what was depicted as a typical Memphis dive of the 1930s. After That Ain't Right with Brown, he reprises his first and most identifiable giant hit Ain't Misbehavin' for the last time on film or record.

|

After he was done with the film Fats went back on tour for a couple of months. He then contributed material to the musical Early to Bed with librettist George Marion Jr., which played for nearly a year on Broadway starting in June, 1943, outlasting him by several months. Stormy Weather hit the screens in early July, and brought a new surge of fame for those who appeared in it, including Fats. In the fall he returned to Southern California to play some engagements. Waller appeared in the Zanzibar Club in Los Angeles during a November warm spell. Given the tight space and conditions with lighting, the obese pianist weighing around 280 pounds had little choice but to perspire at his own efforts while sitting next to an air conditioner to fend off the heat. He kept up the pace as he was heavily advertised in the local papers. Years of moderate to heavy drinking and the stress on his heart from his sheer size weakened his system. The result late in the month was a serious case of influenza that progressed into pneumonia, requiring hospitalization.

Waller seemed to be recovering when he tried to resume his previous level of performance activity. In mid-December he boarded the Santa Fe Super Chief for New York. While talking with his manager, Ed Kirkeby, as they approached Kansas City on the morning of December 15, he started gasping for breath and Kirkeby had a porter summon a physician. Before the doctor could attend to him, his weakened heart gave out, and Thomas Wright Waller, the great jovial master of stride piano, passed on at only 39 years. Three days later his friend and mentor James P. Johnson recorded Blues for Fats. The outpouring of grief from his peers and fans was as enormous as his lust for life, and the loss of Waller created a vacuum in the musical community for some time. Over 4200 people attended services held for Waller in Manhattan. He was survived by his wife Anita, to whom he was still married, and his three children. Thomas Jr. had enlisted in the Army before the draft and was at a camp in Coffeyville, Kansas, that December, while Ronald and Maurice were still in New York.

A Strong and Lasting Legacy

Fortunately for us Fats Waller left behind a joyous legacy of hundreds of compositions, recordings and film appearances. He, along with Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Joe Jordan, was also one of the few black performers who managed to successfully breach racial barriers of the 1930s and 1940s in terms of both integrated performances and musical compositions. He also managed to simplify things that to some seemed musically complex. Concerning the music Fats played, he said, "I am nobody to get mighty about swing. It's just a musical phase of our social life." He later defined his style of swing as "two-thirds rhythm and one-third soul.

who managed to successfully breach racial barriers of the 1930s and 1940s in terms of both integrated performances and musical compositions. He also managed to simplify things that to some seemed musically complex. Concerning the music Fats played, he said, "I am nobody to get mighty about swing. It's just a musical phase of our social life." He later defined his style of swing as "two-thirds rhythm and one-third soul.

who managed to successfully breach racial barriers of the 1930s and 1940s in terms of both integrated performances and musical compositions. He also managed to simplify things that to some seemed musically complex. Concerning the music Fats played, he said, "I am nobody to get mighty about swing. It's just a musical phase of our social life." He later defined his style of swing as "two-thirds rhythm and one-third soul.

who managed to successfully breach racial barriers of the 1930s and 1940s in terms of both integrated performances and musical compositions. He also managed to simplify things that to some seemed musically complex. Concerning the music Fats played, he said, "I am nobody to get mighty about swing. It's just a musical phase of our social life." He later defined his style of swing as "two-thirds rhythm and one-third soul.Several compilations of Waller's recordings found their way to newly-minted RCA Victor LPs in the 1950s, and piano rolls of him or his works obtained a new popularity as well. In the 1960s researchers started taking a more serious look at Waller's life, and both books and growing discographies accumulated throughout that decade and the next one. In 1978 a highly successful revue of his works appropriately titled Ain't Misbehavin' launched into a nearly-four year run which helped launch the career of the late Nell Carter, and it remains a popular property to this day.

Today, more than a century after his birth and seven decades following his death, Waller folios and Waller CDs of his performances of those of contemporary artists are easy enough to find. Virtually any competent jazz or stride musician from Dick Hyman and Judy Carmichael to Brian Holland and Jeff Barnhart can whip out a full set of his tunes, even in duets (the author has played Waller duets with the latter three of those four pianists), without a second thought, he has become such a part of the DNA of American stride and jazz. But then again, as Waller was heard to say from time to time, "One never knows, do one!"