W. Benton Overstreet was born just northwest of Kansas City in the Missouri River town of Atchison, Kansas, to African American stone mason Thomas B. Ward Overstreet and his wife Amelia Lewis. He was one of ten surviving children born to the couple, including Samuel J. (1/1880), Maria L. (4/1886), Guy (5/1886), Emma (6/1891), Hettie C. (8/1893), George Virgil (12/1/1894), Gertrude "Gertie" Meyers (5/1897), Holly Andrew (7/31/1899), and Minnie P. (1903). The 1900 enumeration showed the family still living in Atchison. There is little detail on William's early years or his training, which likely included some musical basics in the segregated public schools of the period, but may also have been derived from some of the pianists and musicians who either worked at local establishments, or traveled through town with a variety of shows. That life was evidently attractive to him, and he somehow obtained enough considerable professional training that he was able to notate and arrange music for ensembles. The 1910 enumeration showed William and some of his family now living in Blue Rapids City, Kansas, with recently widowed Thomas still contracting as a stone mason, and William as a laborer in a traveling show. Also in the home was his wife Carrie, whom Benton had married in 1907 when he was age 19 and she was 18.

The group William was traveling with was William McCabe's Georgia Troubadours, which he had joined some time prior to 1910. Carrie was a dancer in the troupe, but it is not clear if that is where they met. If that was the case, it would backdate his involvement in it to around 1907, but nothing substantive was found to support this. That gig, in which he was cited as a laborer in the census, was actually one that provided opportunities for William to play and direct, as within weeks his name would soon be found in newspapers advertising events he performed in and his true role in the organization. Several months later, on September 15, 1910, when Overstreet had become the musical director of the group, they would be included in a column edited by black writer Lester A. Walton in the New York Age during a visit to Iowa, which gives one a peek into the nature of the company:

McCabe's Georgia Troubadours

September finds us in our old favorite State, Iowa, playing familiar towns and meeting old friends and patrons, and we can always depend upon doing a big business.

The company this season is larger and stronger than ever. Manager McCabe is carrying new special and elaborate scenery, designed and painted by Cox & Co., and It is wonderful to behold. The show is well costumed, and six pretty girls grace the first part setting with beautiful effect.

|

Edna McCabe acts as conversationalist and deserves great credit. William McCabe as a funmaker is considered A1 and overshadows them all. Little Buster McDonald is a diminutive singing and dancing comedian, who will in a short while make much of the older class look to their laurels. Prof. William Overstreet, our efficient musical director, has done more to improve the singing voices than any other Instructor we have had. Prof. Norman Thomas, the sensational ragtime piano player and his charming wife, Rosie Thomas, are with us again, having just finished a summer engagement at Mount Clemens, Mich. Mrs. Thomas has a deep contralto voice and slugs such songs that make people always desire to see and hear her again. Little Carrie Overstreet, justly styled "Cricket," has shown the management and the public that she can sing and dance.

In the same column on November 10, 1910, it was announced that the George Troubadours were now in Overstreet's home territory in Kansas. Subsequent mentions over the next year for appearances throughout the corn belt between Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, Kansas, and Colorado, rarely failed to mention their dynamic music director, William Overstreet. Curiously, some mentions of their pianist varied between Norman and Norma Thompson, so it is unclear if this was an occasional misspelling or a conscious one. Norman's wife Rose was also part of the company. William and Norman were billed by McCabe as "kings of ivory manipulators."

After the 1911-1912 season it appears that the Georgia Troubadours were disbanded, but even before December 1911 the Overstreets had embarked on a journey of their own, as they were no longer listed as part of the company.

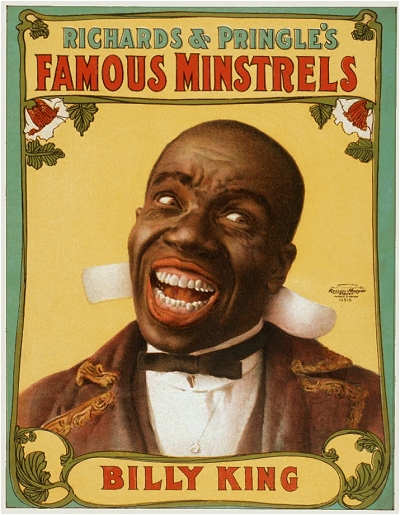

Nothing substantive was found on the Overstreets from late 1911 into 1913 until an August 30, 1913 notice in the Indianapolis Freeman which showed that William was the director of an orchestra for the Lincoln Theater in the resort town of Galveston, Texas. There was no mention of Carrie at this juncture. In early 1914, William, who was now going by W. Benton Overstreet, joined the traveling stock company of comedian Billy King and his wife Hattie McIntosh, both of whom he had likely met while with McCabe, since they often ran in the same circuits. Benton became their musical director for at least the next three seasons into at least September 1916.

|

During their travels, and probably while staying for a series of shows in Mobile, Alabama, Benton submitted his first known published composition, My Place of Bizness, at the end of 1914. In July 1915, the Indianapolis Freeman, in commenting on a vaudeville team performing that song, noted that Benton had other songs in the work that were "too numerous to mention, which he intends to put on the market soon. In fact, that may have been a bit of an exaggeration, but he still had a couple more published during a 1915 summer residency at the Lyric Theater in Kansas City, Missouri with King's troupe. This was soon followed by a short residency in Chicago, Illinois, presenting, among other acts, Hearts of Men at the Grand Theater. During the next season, Benton's last with King, they were seen in Washington, DC at the Howard Theater in March, 1016, not far from the traditionally black school now known as Howard University. The main sketch was titled Neighbors, and it featured both Benton and King. Then it was back to Chicago for a musical titled The Last Rehearsal featuring three songs by Benton that would soon be released, including The Alabama Todelo, referencing a popular dance style of the period that also echoed Eubie Blake's Baltimore Todelo from 1910. (It was mislabeled as Alabama Toledo when copyrighted from Kansas City.) One newspaper mention in the summer of 1915 referred to the Kansas City Todelo by Overstreet, which may have been the same work under a different title. During this stint at the Grand Theater in Chicago, Overstreet was the musical director for both A Mother-in-Law's Disposition and Now I Am a Mason, both of which he wrote some of the music for.

One newspaper mention in the summer of 1915 referred to the Kansas City Todelo by Overstreet, which may have been the same work under a different title. During this stint at the Grand Theater in Chicago, Overstreet was the musical director for both A Mother-in-Law's Disposition and Now I Am a Mason, both of which he wrote some of the music for.

One newspaper mention in the summer of 1915 referred to the Kansas City Todelo by Overstreet, which may have been the same work under a different title. During this stint at the Grand Theater in Chicago, Overstreet was the musical director for both A Mother-in-Law's Disposition and Now I Am a Mason, both of which he wrote some of the music for.

One newspaper mention in the summer of 1915 referred to the Kansas City Todelo by Overstreet, which may have been the same work under a different title. During this stint at the Grand Theater in Chicago, Overstreet was the musical director for both A Mother-in-Law's Disposition and Now I Am a Mason, both of which he wrote some of the music for.There is a story concerning Overstreet's pianistic ability that has some credence concerning one of the better tale-spinners and pianists of that era, Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton, who was still building his reputation in 1915 and 1916. As Morton was largely based in California from late 1915 into 1917, this incident likely happened around the middle of 1915. In Morton's words

Will Overstreet was a newcomer in Chicago, coming with Billy King's Stock Company. He was rated as a great pianist. He was carved [soundly defeated] the first day he came in town by every decent pianist in town.

Overstreet was evidently undaunted and pointed out that he had something unique to offer, claiming in the Indianapolis Freeman that he was "the originator of the long bass which was introduced in [Kansas City] some years ago," and that he would "introduce some new basses which will probably open the eyes of some of the left-handed fellows." It is unclear if this was referring to an early form of walking bass or boogie, with origins ranging from Texas and Kansas City into the Deep South. A later set of recordings with Overstreet as an accompanist show him to be a very competent if not flashy pianist. Also, he was becoming a composer of note. During the King company's stay in Chicago over the summer of 1916, The Broad Ax newspaper reported that in 18 weeks they had "produced and staged 35 original playlets, including lyrics and music. The music was written by his Musical Director, W. Benton Overstreet."

During the King company's stay in Chicago over the summer of 1916, The Broad Ax newspaper reported that in 18 weeks they had "produced and staged 35 original playlets, including lyrics and music. The music was written by his Musical Director, W. Benton Overstreet."

During the King company's stay in Chicago over the summer of 1916, The Broad Ax newspaper reported that in 18 weeks they had "produced and staged 35 original playlets, including lyrics and music. The music was written by his Musical Director, W. Benton Overstreet."

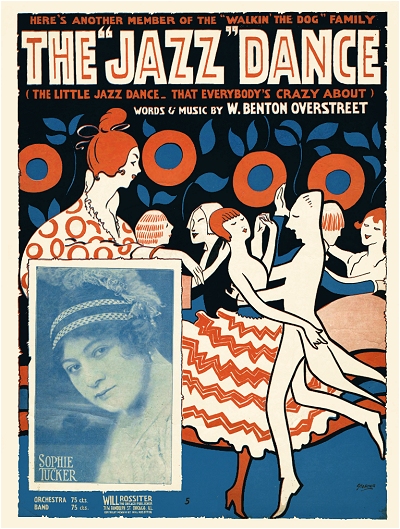

During the King company's stay in Chicago over the summer of 1916, The Broad Ax newspaper reported that in 18 weeks they had "produced and staged 35 original playlets, including lyrics and music. The music was written by his Musical Director, W. Benton Overstreet."There were no mentions of Carrie during these tours, so it is not clear what her status was in Benton's life by 1916. However, it appears they were divorced at some point prior to 1916. Late in the year or in early 1917, Benton was married to Estelle "Stella" Harris, who had been part of the Billy King Stock Company, and with whom he had also written a couple songs. They would perform as their own act starting in 1916 in Chicago, with Benton backing Estelle and the Rag Shouters. One of their show titles was Walking the Dog, possibly a reference to the Shelton Brooks tune of that time. There were a number of new Overstreet numbers in their act as well. The couple continued to tour through 1917 and 1918, with Estelle billed as "The 'Jazz' Queen, Exponent of Syncopation." Benton was an early adopter of the word and style "jass" in early 1917. He further worked with the vaudeville team of Butler "String Beans" May and William "Baby" Benbow, acting as a music director and song contributor. When not in Chicago, Benton and Estelle toured the Midwest with occasional forays into the eastern part of the country. Benton's July 1917 draft record taken in Cincinnati, Ohio, showed his vague home address as in Blue Rapids, Kansas, and his status as married, working for M. Klein in Chicago, but no other helpful details.

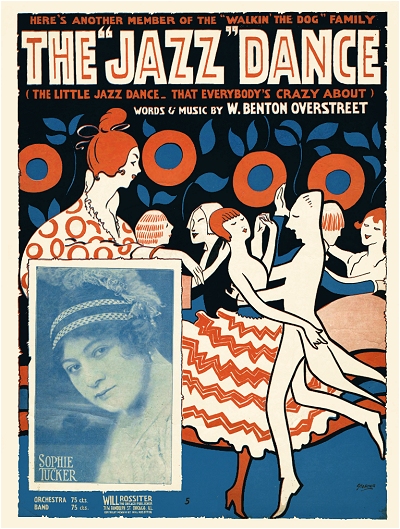

One of Benton's more popular tunes was issued in 1917. The Jazz Dance seemed to resonate with a newly-minted jazz-craving public, and was soon recorded and committed to piano rolls. The Columbia Records disc of the tune by W.C. Handy's orchestra helped to bring Overstreet's name into the forefront, and to cement the tune's success, if only for the short term. It was also considered by some historians to be the first published tune that had the word "jazz" (not "jass") in the title. But he also suffered from a malady that hurt black and white composers alike; other stage acts were stealing his songs without proper recognition or royalties, part of the reason ASCAP had been formed in 1914. He lamented this continuing fight while in residency at the Howard Theater in Washington, DC, in 1917, noting that he was working to keep his compositions "out of the hands of music pirates," one of the earlier uses of that term concerning intellectual rights that remains part of the entertainment world more than a century later. But some acts, both black and white, legitimately adopted his songs, adding to his success.

The Columbia Records disc of the tune by W.C. Handy's orchestra helped to bring Overstreet's name into the forefront, and to cement the tune's success, if only for the short term. It was also considered by some historians to be the first published tune that had the word "jazz" (not "jass") in the title. But he also suffered from a malady that hurt black and white composers alike; other stage acts were stealing his songs without proper recognition or royalties, part of the reason ASCAP had been formed in 1914. He lamented this continuing fight while in residency at the Howard Theater in Washington, DC, in 1917, noting that he was working to keep his compositions "out of the hands of music pirates," one of the earlier uses of that term concerning intellectual rights that remains part of the entertainment world more than a century later. But some acts, both black and white, legitimately adopted his songs, adding to his success.

The Columbia Records disc of the tune by W.C. Handy's orchestra helped to bring Overstreet's name into the forefront, and to cement the tune's success, if only for the short term. It was also considered by some historians to be the first published tune that had the word "jazz" (not "jass") in the title. But he also suffered from a malady that hurt black and white composers alike; other stage acts were stealing his songs without proper recognition or royalties, part of the reason ASCAP had been formed in 1914. He lamented this continuing fight while in residency at the Howard Theater in Washington, DC, in 1917, noting that he was working to keep his compositions "out of the hands of music pirates," one of the earlier uses of that term concerning intellectual rights that remains part of the entertainment world more than a century later. But some acts, both black and white, legitimately adopted his songs, adding to his success.

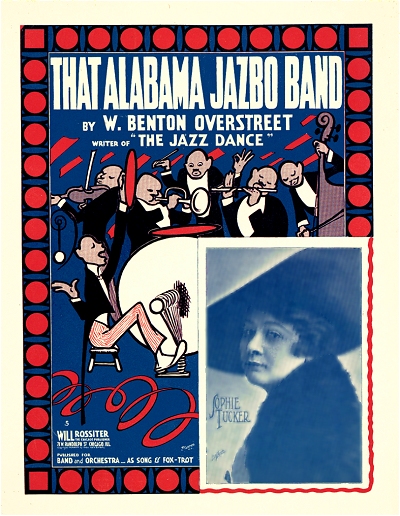

The Columbia Records disc of the tune by W.C. Handy's orchestra helped to bring Overstreet's name into the forefront, and to cement the tune's success, if only for the short term. It was also considered by some historians to be the first published tune that had the word "jazz" (not "jass") in the title. But he also suffered from a malady that hurt black and white composers alike; other stage acts were stealing his songs without proper recognition or royalties, part of the reason ASCAP had been formed in 1914. He lamented this continuing fight while in residency at the Howard Theater in Washington, DC, in 1917, noting that he was working to keep his compositions "out of the hands of music pirates," one of the earlier uses of that term concerning intellectual rights that remains part of the entertainment world more than a century later. But some acts, both black and white, legitimately adopted his songs, adding to his success.Another mildly popular song came from Benton's pen in 1918 in the form of That Alabama Jazbo Band, published in Chicago. It appears to be the only output of that year, which was largely populated by songs about the ongoing war. However, Benton and Estelle continued to tour theaters in the Midwest and East from Chicago to the Chesapeake Bay, including a run at the Standard Theater in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania some months after the war had ended. However, it appears that the partnership and marriage was also at its end in 1919, as Estelle's name disappeared from mentions of Overstreet late in the year. The 1920 enumeration yielded nothing on Overstreet, but newspaper notices suggest he was still in Philadelphia at the Standard, and by 1921 at the Dunbar Theater.

Benton was, in fact, now acquainted with singer Eva Walker, a member of the Mills and Frisby stock company, who likely had visited the Standard for a stint in 1920. It was suggested in the Chicago Defender of August 28, 1920, that the pair were to be wed on September 1st. No record of that union was found, so the status is still unknown. If they were indeed wed, it would be for the short term, as Eva's name soon also disappears from mentions of Benton. In 1921 Overstreet teamed up with another vaudevillian peer, Billy Higgins, to write There'll Be Some Changes Made, which a century and more later remains his most popular and oft-played tune. The initial recording of this was rendered on the Black Swan label by no less than Ethel Waters, who was on her way to fame in 1921. The song's chorus contained what would become a popular chord progression in the 1920s, and a repeated phrase at the end that was often a staple of later vaudeville songs, which carried over into traditional jazz pieces. Since it came out the piece has been recorded dozens of times by popular artists, jazz bands, honky-tonk pianists, skilled keyboardists like Oscar Peterson and Art Tatum, and even some country and western bands.

No record of that union was found, so the status is still unknown. If they were indeed wed, it would be for the short term, as Eva's name soon also disappears from mentions of Benton. In 1921 Overstreet teamed up with another vaudevillian peer, Billy Higgins, to write There'll Be Some Changes Made, which a century and more later remains his most popular and oft-played tune. The initial recording of this was rendered on the Black Swan label by no less than Ethel Waters, who was on her way to fame in 1921. The song's chorus contained what would become a popular chord progression in the 1920s, and a repeated phrase at the end that was often a staple of later vaudeville songs, which carried over into traditional jazz pieces. Since it came out the piece has been recorded dozens of times by popular artists, jazz bands, honky-tonk pianists, skilled keyboardists like Oscar Peterson and Art Tatum, and even some country and western bands.

No record of that union was found, so the status is still unknown. If they were indeed wed, it would be for the short term, as Eva's name soon also disappears from mentions of Benton. In 1921 Overstreet teamed up with another vaudevillian peer, Billy Higgins, to write There'll Be Some Changes Made, which a century and more later remains his most popular and oft-played tune. The initial recording of this was rendered on the Black Swan label by no less than Ethel Waters, who was on her way to fame in 1921. The song's chorus contained what would become a popular chord progression in the 1920s, and a repeated phrase at the end that was often a staple of later vaudeville songs, which carried over into traditional jazz pieces. Since it came out the piece has been recorded dozens of times by popular artists, jazz bands, honky-tonk pianists, skilled keyboardists like Oscar Peterson and Art Tatum, and even some country and western bands.

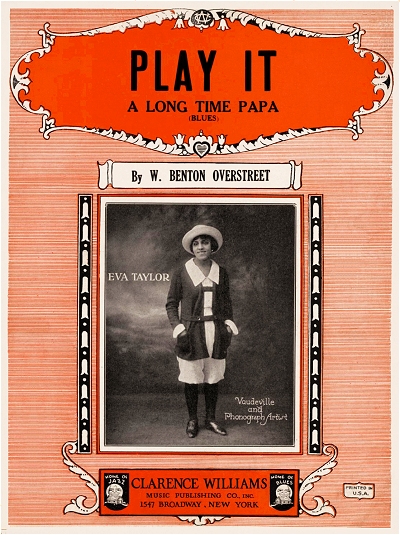

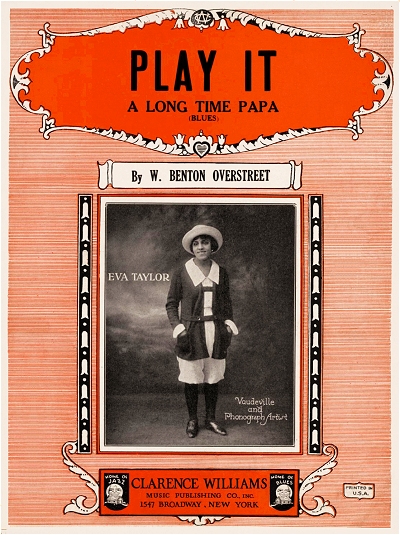

No record of that union was found, so the status is still unknown. If they were indeed wed, it would be for the short term, as Eva's name soon also disappears from mentions of Benton. In 1921 Overstreet teamed up with another vaudevillian peer, Billy Higgins, to write There'll Be Some Changes Made, which a century and more later remains his most popular and oft-played tune. The initial recording of this was rendered on the Black Swan label by no less than Ethel Waters, who was on her way to fame in 1921. The song's chorus contained what would become a popular chord progression in the 1920s, and a repeated phrase at the end that was often a staple of later vaudeville songs, which carried over into traditional jazz pieces. Since it came out the piece has been recorded dozens of times by popular artists, jazz bands, honky-tonk pianists, skilled keyboardists like Oscar Peterson and Art Tatum, and even some country and western bands.Whether or not Benton and Eva were legally wed or just cohabitating (her name was never changed), they would stay together through at least 1923, plying the boards of varying theaters and vaudeville houses. One large event was held in September 1922 at the Dellinger Theater in Batavia, New York, where Benton was once again leading the "Famous Dark Day Orchestra" for Billy King and his "forty Creole Bootleggers in a pre-Volstead Musical Highball, 'Moonshine.'" He was also still writing with Higgins, producing Early Every Morn' (I Want My Lovin'), which would see some fame in 1924 as recorded by blues singer Alberta Hunter accompanied by the trumpet of Louis Armstrong. The strength and quality of Benton's writing put him in good stead with black composer/publisher Clarence Williams, who took him on for a while starting in 1923. Williams published some of Overstreet's songs. Among them was one that featured Eva on the cover, Play It a Long Time Papa. When it was finally recorded it took on the somewhat more suggestive title of Do It a Long Time Papa. Most of the remaining tunes by Benton from the 1923 to 1925 period were average urban blues or semi-popular material of that time, with no real standouts. There were even two numbers that referenced The Charleston, the iconic 1920s dance craze fueled by the piece of the same name by Jaems P. Johnson and R.C. Mc Pherson (a.k.a. Cecil Mack).

where Benton was once again leading the "Famous Dark Day Orchestra" for Billy King and his "forty Creole Bootleggers in a pre-Volstead Musical Highball, 'Moonshine.'" He was also still writing with Higgins, producing Early Every Morn' (I Want My Lovin'), which would see some fame in 1924 as recorded by blues singer Alberta Hunter accompanied by the trumpet of Louis Armstrong. The strength and quality of Benton's writing put him in good stead with black composer/publisher Clarence Williams, who took him on for a while starting in 1923. Williams published some of Overstreet's songs. Among them was one that featured Eva on the cover, Play It a Long Time Papa. When it was finally recorded it took on the somewhat more suggestive title of Do It a Long Time Papa. Most of the remaining tunes by Benton from the 1923 to 1925 period were average urban blues or semi-popular material of that time, with no real standouts. There were even two numbers that referenced The Charleston, the iconic 1920s dance craze fueled by the piece of the same name by Jaems P. Johnson and R.C. Mc Pherson (a.k.a. Cecil Mack).

where Benton was once again leading the "Famous Dark Day Orchestra" for Billy King and his "forty Creole Bootleggers in a pre-Volstead Musical Highball, 'Moonshine.'" He was also still writing with Higgins, producing Early Every Morn' (I Want My Lovin'), which would see some fame in 1924 as recorded by blues singer Alberta Hunter accompanied by the trumpet of Louis Armstrong. The strength and quality of Benton's writing put him in good stead with black composer/publisher Clarence Williams, who took him on for a while starting in 1923. Williams published some of Overstreet's songs. Among them was one that featured Eva on the cover, Play It a Long Time Papa. When it was finally recorded it took on the somewhat more suggestive title of Do It a Long Time Papa. Most of the remaining tunes by Benton from the 1923 to 1925 period were average urban blues or semi-popular material of that time, with no real standouts. There were even two numbers that referenced The Charleston, the iconic 1920s dance craze fueled by the piece of the same name by Jaems P. Johnson and R.C. Mc Pherson (a.k.a. Cecil Mack).

where Benton was once again leading the "Famous Dark Day Orchestra" for Billy King and his "forty Creole Bootleggers in a pre-Volstead Musical Highball, 'Moonshine.'" He was also still writing with Higgins, producing Early Every Morn' (I Want My Lovin'), which would see some fame in 1924 as recorded by blues singer Alberta Hunter accompanied by the trumpet of Louis Armstrong. The strength and quality of Benton's writing put him in good stead with black composer/publisher Clarence Williams, who took him on for a while starting in 1923. Williams published some of Overstreet's songs. Among them was one that featured Eva on the cover, Play It a Long Time Papa. When it was finally recorded it took on the somewhat more suggestive title of Do It a Long Time Papa. Most of the remaining tunes by Benton from the 1923 to 1925 period were average urban blues or semi-popular material of that time, with no real standouts. There were even two numbers that referenced The Charleston, the iconic 1920s dance craze fueled by the piece of the same name by Jaems P. Johnson and R.C. Mc Pherson (a.k.a. Cecil Mack).As per The Billboard of March 24, 1923, Benton recorded some tracks on the Black Swan race record label with singer Maude De Forest from the stage team of Smith and De Forest. Maud would later go to France and grace the same stages as Geraldine Baker, sometimes replacing her in a show. However, this set of recordings was evidently never released on Black Swan or any other label. Undaunted, Benton continued to play and write, another one of his contributions in 1923 being the musical play Swanee Reiver Home to a libretto by Sandy Burns. In 1924 he was back in Philadelphia at the Dunbar Theater managed by John T. Gibson,

and notices in the theatrical trades showed him touring a few months later in the Creole Follies, which played in both Chicago and Philadelphia. It is unclear if he contributed any music to it. A sketchy situation occurred in the late summer of 1925 when while working in Hot Springs, Arkansas, one of his former partners, William Sellman, accused Benton of making off with some wardrobe and props from a show they had recently been in. Overstreet was put in jail awaiting a charge of grand larceny. There is a possibility that this was the result of a feud between the two men, since charges were soon dropped, and Benton was able to continue his tour. Later in the year he joined the company of Samuel H. Gray and Virginia Liston, the latter being a blues singer whom he had written music for in 1923. He closed out the year with them after a busy Midwest tour.

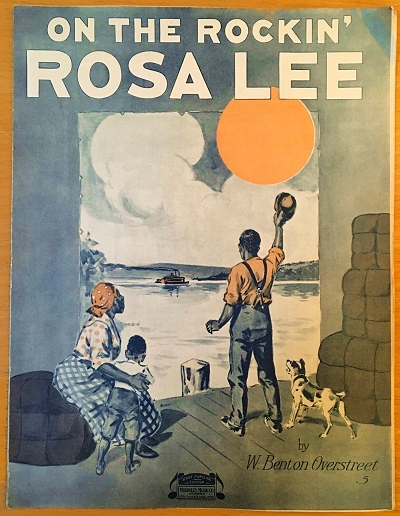

|

By 1926, even with a firm reputation as a composer and leader, Benton was still living somewhat as an itinerant musician, lodging in whichever town he was playing, but with no true fixed address. By 1926 he was based once again in Chicago, sans Eva, and working with Wharton's Snappy Gingers as the music director. He took a hiatus at the end of the year, returning to Kansas City for a while. Then, in 1927, most likely in Chicago, he got another crack at recording. Overstreet contributed accompaniment to blues singer Elnora Johnson on four sides for the Black Patti label, which was based in New York. All of the tracks, including Freakish Papa, I Like That Thing (Called the Black Bottom), Black Bottom Blues and Red Cap Porter Blues were Overstreet originals, the last one co-written with Johnson. A century later they show him to be perhaps a better pianist than Morton had claimed, but there was also another decade of experience behind him. The only other known recordings of Benton as accompanist appeared in 1929 on the more widely distributed Brunswick label when he played with singer Sam Theard. However, only one of the four sides included an Overstreet original, Get It in Front.

Then, in 1927, most likely in Chicago, he got another crack at recording. Overstreet contributed accompaniment to blues singer Elnora Johnson on four sides for the Black Patti label, which was based in New York. All of the tracks, including Freakish Papa, I Like That Thing (Called the Black Bottom), Black Bottom Blues and Red Cap Porter Blues were Overstreet originals, the last one co-written with Johnson. A century later they show him to be perhaps a better pianist than Morton had claimed, but there was also another decade of experience behind him. The only other known recordings of Benton as accompanist appeared in 1929 on the more widely distributed Brunswick label when he played with singer Sam Theard. However, only one of the four sides included an Overstreet original, Get It in Front.

Then, in 1927, most likely in Chicago, he got another crack at recording. Overstreet contributed accompaniment to blues singer Elnora Johnson on four sides for the Black Patti label, which was based in New York. All of the tracks, including Freakish Papa, I Like That Thing (Called the Black Bottom), Black Bottom Blues and Red Cap Porter Blues were Overstreet originals, the last one co-written with Johnson. A century later they show him to be perhaps a better pianist than Morton had claimed, but there was also another decade of experience behind him. The only other known recordings of Benton as accompanist appeared in 1929 on the more widely distributed Brunswick label when he played with singer Sam Theard. However, only one of the four sides included an Overstreet original, Get It in Front.

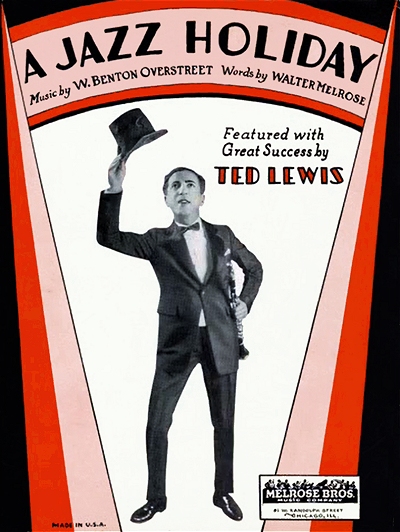

Then, in 1927, most likely in Chicago, he got another crack at recording. Overstreet contributed accompaniment to blues singer Elnora Johnson on four sides for the Black Patti label, which was based in New York. All of the tracks, including Freakish Papa, I Like That Thing (Called the Black Bottom), Black Bottom Blues and Red Cap Porter Blues were Overstreet originals, the last one co-written with Johnson. A century later they show him to be perhaps a better pianist than Morton had claimed, but there was also another decade of experience behind him. The only other known recordings of Benton as accompanist appeared in 1929 on the more widely distributed Brunswick label when he played with singer Sam Theard. However, only one of the four sides included an Overstreet original, Get It in Front.In between those sessions, in early 1928, Benton unleashed his composition A Jazz Holiday into the world. It was soon picked up by future superstar bandleader and clarinetist Benny Goodman who recorded it with his small ensemble that January, the same month it was issued. Goodman's mentor, the ever-popular Ted Lewis, followed in short order with his own rendition. The piece was grandly touted in The Billboard of February 4, 1928:

A Jazz Holiday is the title of a brand new number being published by Melrose Bros, and from the interest shown by orchestra leaders it will be a real Melrose hit. W. Benton Overstreet, an expert and authority on the jazz style of songs, is the creator of the so-different melody in A Jazz Holiday, a Dixieland stomp, a song that will probably sweep the country in short time. Overstreet has written many other hits, but those in the "know" say his new number will top them all.

Benton continued the arduous road trips late into the year, but it appeared that his lifestyle was taking a toll on the pianist. In 1929 the Chicago Defender made reference to him currently residing northwest in Madison, Wisconsin, where he was "resting." As there had been allusions in the trades over the past few years to Overstreet being "on the wagon," that being the water wagon, it is a subtle indication that he, like many of his peers, was having some issues with alcohol. This may have been compounded by the fact that National Prohibition was in full swing, making booze a national evil that was nonetheless readily available to those who wanted it, particularly those in show business. In fact, it was said in the Defender a year later in May 1930 that he had been told by his doctor that his choice was between foregoing alcohol or facing an early death. However, after a few months of recovery, Benton returned to Chicago where he played for the Sam Theard sessions, then went back into the fray as a musical director for a show at the Columbia Theater in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

As there had been allusions in the trades over the past few years to Overstreet being "on the wagon," that being the water wagon, it is a subtle indication that he, like many of his peers, was having some issues with alcohol. This may have been compounded by the fact that National Prohibition was in full swing, making booze a national evil that was nonetheless readily available to those who wanted it, particularly those in show business. In fact, it was said in the Defender a year later in May 1930 that he had been told by his doctor that his choice was between foregoing alcohol or facing an early death. However, after a few months of recovery, Benton returned to Chicago where he played for the Sam Theard sessions, then went back into the fray as a musical director for a show at the Columbia Theater in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

As there had been allusions in the trades over the past few years to Overstreet being "on the wagon," that being the water wagon, it is a subtle indication that he, like many of his peers, was having some issues with alcohol. This may have been compounded by the fact that National Prohibition was in full swing, making booze a national evil that was nonetheless readily available to those who wanted it, particularly those in show business. In fact, it was said in the Defender a year later in May 1930 that he had been told by his doctor that his choice was between foregoing alcohol or facing an early death. However, after a few months of recovery, Benton returned to Chicago where he played for the Sam Theard sessions, then went back into the fray as a musical director for a show at the Columbia Theater in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

As there had been allusions in the trades over the past few years to Overstreet being "on the wagon," that being the water wagon, it is a subtle indication that he, like many of his peers, was having some issues with alcohol. This may have been compounded by the fact that National Prohibition was in full swing, making booze a national evil that was nonetheless readily available to those who wanted it, particularly those in show business. In fact, it was said in the Defender a year later in May 1930 that he had been told by his doctor that his choice was between foregoing alcohol or facing an early death. However, after a few months of recovery, Benton returned to Chicago where he played for the Sam Theard sessions, then went back into the fray as a musical director for a show at the Columbia Theater in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.The 1930 census showed Benton back in Milwaukee and presents a couple of curiosities. First, even though he was still playing out, at this point working on and off with the band of Jimmy Wade, he was noted as now teaching piano. Also of interest is the presence of yet another wife, this one named Amanda F. Overstreet. Searches turned up no marriage certificate, so it may have been another common-law situation. She has also been married before, showing her first having occurred in 1920. One or both of them also spun a tale, with Amanda, a dressmaker, showing as 26, meaning she was married at 16, and Benton as a mere 35 to his actual 42. It is known that Benton continued to work into late 1930 with the Wad organization, including a stint in Toledo, Ohio, that fall. The following year he composed a pair of songs with William Austin and Louis Rich, both of Milwaukee. Little else was heard from him through 1932 except that he possibly had undergone some kind of surgery, and was still playing out now and then.

The next sighting of Benton was in Detroit, Michigan, in 1933. From May forward he was working as the orchestra leader for the Lucky Girl Company front by David Wiles, and in residence at the Castle Theater. Later in the year Benton switched to another venue, as noted in The Billboard of December 16, 1933, in their Burlesque Theater section:

The Dunbar Theater, former picture house, has been reopened with a vaude-tabloid policy under ownership of John O'Dell, theater circuit owner. Andrew Jackanic is general manager, with William Gesch house manager. House caters to colored patronage. Benton Overstreet is conductor of the orchestra and Kid Williams is master of ceremonies. Several acts of vaudeville are used, the principals and all acts changing weekly.

As close as they were to the Canadian border, it was not uncommon for Detroit acts to spend some time in Windsor, Ontario, a tradition going back to the early part of the century. So it was that Benton and others were seen either performing or visiting theaters there in early 1934, as noted in a February edition of the Defender. Benton also copyrighted a song from the growing motor city near the end of the year.

It was either in late 1934 or early 1935 the Benton decided to change venues once again, moving to New York City. His main point of contact there was still likely Clarence Williams, who took on a handful of Overstreet's tunes for publication that April. Beyond that, there was nothing of note found in 1935 publications concerning his activity, which may have been due to ill health while he was staying at 437 52nd Street near the jazz clubs and the theater district. Whatever plans he had were cut short in June when he died in Manhattan. Benton was laid to rest in Delaware, New Jersey in early July. But he did not leave behind nothing, and in reference to his contributions to popular music and the notoriety of black composers and performers, there were, indeed, some changes made.

Information on W. Benton Overstreet's life was largely derived from a not insubstantial amount of mentions and advertisements in music trade papers and newspapers in general from the 1910s forward. Historical accounts of both performers and recording sessions were also of some help in constructing the narrative. Much of the remaining information was taken from mentions in interviews with his peers, and the usual government records and scant city directory entries.

Compositions

Compositions