The story of Gotham-Attucks music is both inspiring and heartbreaking, epitomizing in some ways the struggle of black people in general and black musicians and composers specifically during the early 20th century in the highly competitive field of popular music. It involved men of dignity, men with good intentions, men with anger, and one man with less than honorable intentions who inadvertently sullied the name and reputation of the company. It also shows many close calls that clearly made the difference between the success or failure of the company, most of them having to do with the brute force of more powerful entities and pre-existing alliances. In short, Gotham-Attucks can be compared to a Greek tragedy on many levels when considering its seven year history.

Attucks Music Publishing Company - The Pioneer

Two of the challenges faced by any composer who was not a white male in the late 1890s and early 1900s were getting their work published and getting a fair deal in the process. The second component was the hardest to achieve, as many blacks in New York in particular saw their work in print, but usually for a meager buy-out rather than on a royalty basis or even a fair acquisition price. The answer to this problem, so it seemed to some, was to form a company run by black composers and businessmen that was geared to compete with the white publishers.

So it was that an attempt was made in this regard with the opening of Attucks Music Publishing Company on August 13, 1904, at 1255-57 Broadway near 32nd Street in Manhattan. (The year 1903 has been cited, but evidence from newspapers, The Music Trade Review of August 20, and extant legal documents all suggest a very definitive August of 1904 incorporation.) The company, founded by Shephard Edmonds, Jesse A. Shipp and Bert A. Williams, and incorporated with a capital investment of $2,500, was named for Crispus Attucks, who was the first black seaman to die in the American Revolutionary War in 1770 during the Boston Massacre. It would be a name that any black person with some level of education about their own history would quickly recognize, and through that homage gave the intent of the company a clear meaning. As it was announced in the August 20, 1904 edition of the Music Trade Review, "All the parties are colored song writers of more or less celebrity in their specialties. Mr. Edmunds [sic] is the manager..." An advertisement in the New York Clipper a week later indicated that they also had an office at Steinway Hall in Chicago, Illinois.

Shepard Nathaniel Edmonds was born in Memphis, Tennessee, but grew up mostly in central Ohio. He was one of six children born to William Edmonds and Regina Davney, the others being William, Jr. (1865), Alice C. (1869), Francis (1873), Robert (1876) and Rockson (1878). While Shephard's birth year has traditionally been cited as 1876, the 1880 census, showing him to be nine (interpreted here as just ahead of his actual ninth birthday) clearly indicates otherwise. Even at that, from the early 1900s forward Shepard would trim a few years off his actual age in official records. The 1880 record showed William working as a cook to support his large family. Shep's primary musical training was in the public school system, where he learned both piano and percussion, particularly mallet instruments. In the early 1890s he managed to get into Ohio State University where he took business courses and got some medical training with an eye on being a physician. However, his musical side soon lured him into a different calling. There is a chance that he was influenced by music of his race that he heard while attending the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in August of 1893. This is where some of the first wide exposure of the stirrings of ragtime is said to have occurred.

the others being William, Jr. (1865), Alice C. (1869), Francis (1873), Robert (1876) and Rockson (1878). While Shephard's birth year has traditionally been cited as 1876, the 1880 census, showing him to be nine (interpreted here as just ahead of his actual ninth birthday) clearly indicates otherwise. Even at that, from the early 1900s forward Shepard would trim a few years off his actual age in official records. The 1880 record showed William working as a cook to support his large family. Shep's primary musical training was in the public school system, where he learned both piano and percussion, particularly mallet instruments. In the early 1890s he managed to get into Ohio State University where he took business courses and got some medical training with an eye on being a physician. However, his musical side soon lured him into a different calling. There is a chance that he was influenced by music of his race that he heard while attending the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in August of 1893. This is where some of the first wide exposure of the stirrings of ragtime is said to have occurred.

the others being William, Jr. (1865), Alice C. (1869), Francis (1873), Robert (1876) and Rockson (1878). While Shephard's birth year has traditionally been cited as 1876, the 1880 census, showing him to be nine (interpreted here as just ahead of his actual ninth birthday) clearly indicates otherwise. Even at that, from the early 1900s forward Shepard would trim a few years off his actual age in official records. The 1880 record showed William working as a cook to support his large family. Shep's primary musical training was in the public school system, where he learned both piano and percussion, particularly mallet instruments. In the early 1890s he managed to get into Ohio State University where he took business courses and got some medical training with an eye on being a physician. However, his musical side soon lured him into a different calling. There is a chance that he was influenced by music of his race that he heard while attending the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in August of 1893. This is where some of the first wide exposure of the stirrings of ragtime is said to have occurred.

the others being William, Jr. (1865), Alice C. (1869), Francis (1873), Robert (1876) and Rockson (1878). While Shephard's birth year has traditionally been cited as 1876, the 1880 census, showing him to be nine (interpreted here as just ahead of his actual ninth birthday) clearly indicates otherwise. Even at that, from the early 1900s forward Shepard would trim a few years off his actual age in official records. The 1880 record showed William working as a cook to support his large family. Shep's primary musical training was in the public school system, where he learned both piano and percussion, particularly mallet instruments. In the early 1890s he managed to get into Ohio State University where he took business courses and got some medical training with an eye on being a physician. However, his musical side soon lured him into a different calling. There is a chance that he was influenced by music of his race that he heard while attending the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in August of 1893. This is where some of the first wide exposure of the stirrings of ragtime is said to have occurred.In the mid-1890s Edmonds became a percussionist for the Al G. Fields Minstrel Company, touring the Midwest, East and South of the country, but based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. During his tenure with the large Fields company, Shep became one of their stars as a drummer, and then as a comedian and singer. When he was not engaged by them, Shep worked as a private detective in Philadelphia. Around 1897 he joined a black vaudeville troupe for a show called Darkest America which had a wide variety of musical acts and tableaus. After a season with them he found himself in New York City, and decided to strike out on his own as a vaudeville act, teaming up with some other performers now and then, many of them white. Among them were Nellie and Rose Beaumont from England, known as the Beaumont Sisters on stage. Another was white entertainer Charles B. Ward, who was known for his song The Band Played On, still played in the 21st century. Edmonds and Ward wrote a couple of songs together, which were Shep's first published works.

Over the next few years Edmonds managed to take bigger stages with more entertaining acts, and started writing some of his own music material, which was published by the houses of Joseph Stern and M. Witmark. One of the more enduring hits from 1901 was I'm Goin' to Live Anyhow, Till I Die, which was featured separately by black entertainers Ernest Hogan (to whom it was dedicated) and Eddie Leonard. Another hit from 1903 which was featured by esteemed white singer and composer Marie Cahill was You Can't Fool All the People All the Time. Shep made some considerable income from these and other songs, but may not have felt he was getting the best possible deal, nor were many of his peers of color. So he took his earnings and sunk them into Attucks Music, also pulling in famed vaudeville entertainer Bert Williams whose name had considerable import and composer Jesse Shipp who was similarly connected.

One of the more enduring hits from 1901 was I'm Goin' to Live Anyhow, Till I Die, which was featured separately by black entertainers Ernest Hogan (to whom it was dedicated) and Eddie Leonard. Another hit from 1903 which was featured by esteemed white singer and composer Marie Cahill was You Can't Fool All the People All the Time. Shep made some considerable income from these and other songs, but may not have felt he was getting the best possible deal, nor were many of his peers of color. So he took his earnings and sunk them into Attucks Music, also pulling in famed vaudeville entertainer Bert Williams whose name had considerable import and composer Jesse Shipp who was similarly connected.

One of the more enduring hits from 1901 was I'm Goin' to Live Anyhow, Till I Die, which was featured separately by black entertainers Ernest Hogan (to whom it was dedicated) and Eddie Leonard. Another hit from 1903 which was featured by esteemed white singer and composer Marie Cahill was You Can't Fool All the People All the Time. Shep made some considerable income from these and other songs, but may not have felt he was getting the best possible deal, nor were many of his peers of color. So he took his earnings and sunk them into Attucks Music, also pulling in famed vaudeville entertainer Bert Williams whose name had considerable import and composer Jesse Shipp who was similarly connected.

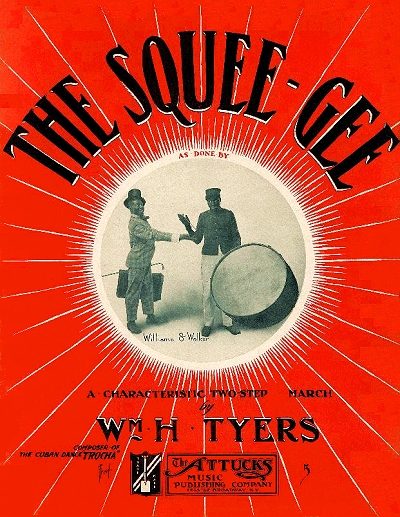

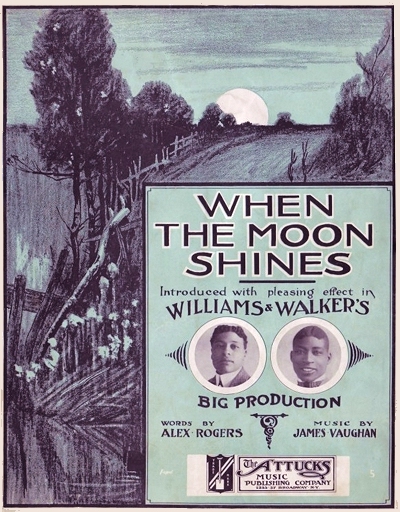

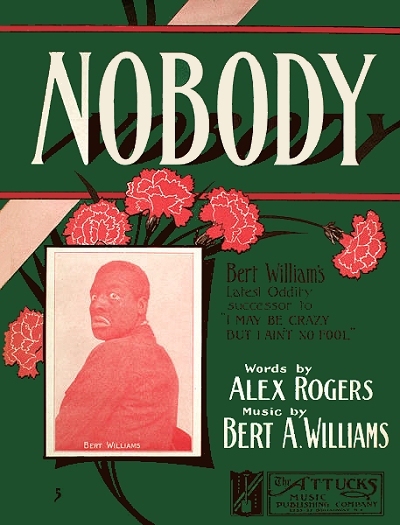

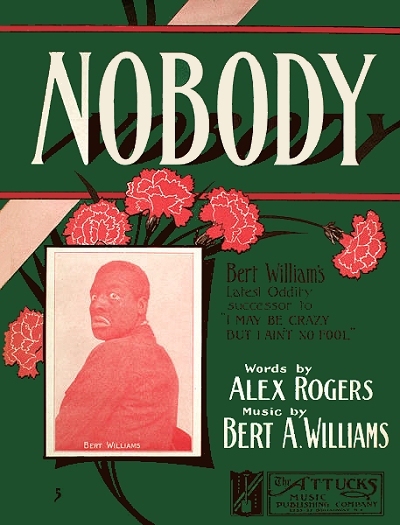

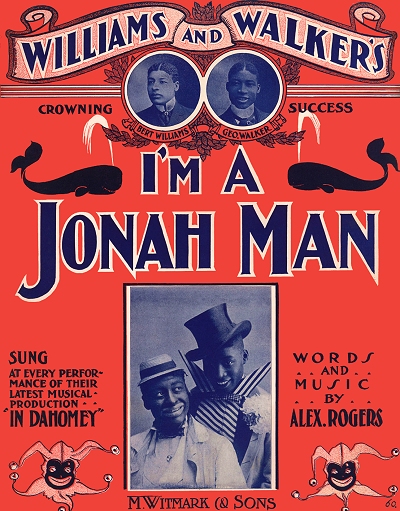

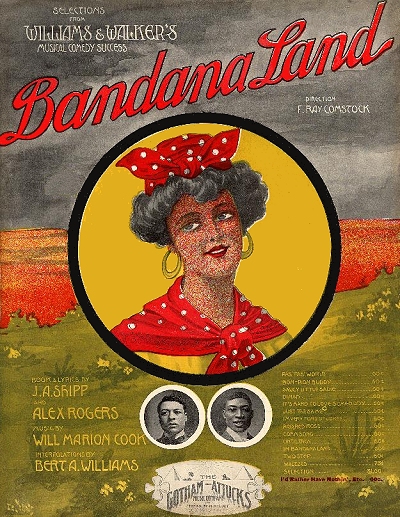

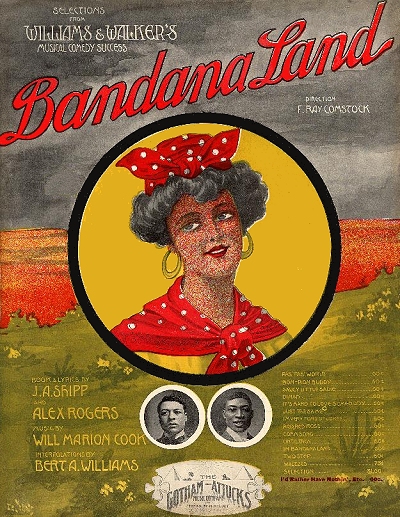

One of the more enduring hits from 1901 was I'm Goin' to Live Anyhow, Till I Die, which was featured separately by black entertainers Ernest Hogan (to whom it was dedicated) and Eddie Leonard. Another hit from 1903 which was featured by esteemed white singer and composer Marie Cahill was You Can't Fool All the People All the Time. Shep made some considerable income from these and other songs, but may not have felt he was getting the best possible deal, nor were many of his peers of color. So he took his earnings and sunk them into Attucks Music, also pulling in famed vaudeville entertainer Bert Williams whose name had considerable import and composer Jesse Shipp who was similarly connected.Even though he had his own firm now, it appears that Edmonds did not immediately publish any of his own works, possibly inhibited from composing by the enormous responsibility of managing his own firm. Just finding good material to issue took a great deal of effort, since many of the songs that Williams and his comedic stage partner George W. Walker were performing on New York stages were already committed to publishers such as Stern, Witmark, and newcomer Harry Von Tilzer. In 1904, Williams and Walker were performing in the pioneering In Dahomey which had done well in London and the UK, and was gaining traction in New York. While most of the interpolated pieces were spoken for, Shep managed to obtain three that were unpublished, even though he was not allowed to use the name of the show on the covers. Using the pictures and names of the stars, however, was enough to make the association. This included Why Adam Sinned by Alex Rogers, with a picture of Bert's wife, Aida Overton Walker, prominently situated on the cover, and I May Be Crazy But I Ain't No Fool, also by Rogers.

The mission of the firm was clearly stated in portions of an extensive article on the "New Coon Music Publishing House" by the "Dahomey Contingent" in the New York Sunday Telegraph of September 4, 1904:

Twenty minutes afterward an aggregation of talent was formed. Shepard [sic] [N.] Edmonds was made manager, offices were rented and the wheels of business began to spin... When a good resolve is born twins, it is time for the business bachelors to awake. There is something doing.

[Bert Williams:] "The members of our firm are all colored. We have a ministerial placard of individuality that must make rag-time perpetual. We know what is worth while in popular music, and we intend to stick to superiority." That's their motto. "There will be no restrictions — the firm will consider all kinds of music, and will be ready at any time to give their attention to Wagnerian opera or melody of ebony hue. In short, the Attucks Company will not be a hotbed of rag-time — the tentacles of this concern will reach out for love-lorn notes washed by the tide of eternal sentiment or the soothing lullabies of the wee mite who wants father to come home...

"We will not draw the line at anything. If a song comes in that prates the glory of a badger it shall go down into musical history, but rag comes first. New York must live up to its old traditions, and May Irwin and Marie Cahill shall be cared for as long as the watermelon sprouts. Rag-time is a natural consequence of the art — there is always a titling [rhythm] in negro [sic] songs — they were born with it in their hearts, and you can't get it out. New ideas — new schemes — a new rag-time is our purpose. We want to originate a new scheme that will perpetuate rag."

These were lofty ideals, perhaps massaged a bit by the writer, but Williams was clearly a major component of the company and appeared to have certain expectations of the new enterprise. As for Shep, when it came to his own material, he finally did try to issue some of it, which immediately got him in trouble, barely five months after his company was founded. Marie Cahill wanted to perform his piece Business is Business in a Lew Fields show that was largely written by Victor Herbert. In order to keep the insistent singer happy, Herbert reportedly had the song purchased outright from Edmonds by Cahill's husband Dan Arthur. However, as reported in the December 3, 1904 edition of the Music Trade Review, Stern still had a grip on him through an older contract in which they had exclusive rights to his compositions. Edmonds claimed the contract had expired even before he wrote Business is Business, but Stern's lawyers said they had evidence to the contrary. A restraining order was granted to Stern along with a $300 bond to cover damages. This was one of at least two court battles between Edmonds and Stern in the latter half of 1904, the other being over some of his other works that he wanted to issue under the Attucks label.

However, as reported in the December 3, 1904 edition of the Music Trade Review, Stern still had a grip on him through an older contract in which they had exclusive rights to his compositions. Edmonds claimed the contract had expired even before he wrote Business is Business, but Stern's lawyers said they had evidence to the contrary. A restraining order was granted to Stern along with a $300 bond to cover damages. This was one of at least two court battles between Edmonds and Stern in the latter half of 1904, the other being over some of his other works that he wanted to issue under the Attucks label.

However, as reported in the December 3, 1904 edition of the Music Trade Review, Stern still had a grip on him through an older contract in which they had exclusive rights to his compositions. Edmonds claimed the contract had expired even before he wrote Business is Business, but Stern's lawyers said they had evidence to the contrary. A restraining order was granted to Stern along with a $300 bond to cover damages. This was one of at least two court battles between Edmonds and Stern in the latter half of 1904, the other being over some of his other works that he wanted to issue under the Attucks label.

However, as reported in the December 3, 1904 edition of the Music Trade Review, Stern still had a grip on him through an older contract in which they had exclusive rights to his compositions. Edmonds claimed the contract had expired even before he wrote Business is Business, but Stern's lawyers said they had evidence to the contrary. A restraining order was granted to Stern along with a $300 bond to cover damages. This was one of at least two court battles between Edmonds and Stern in the latter half of 1904, the other being over some of his other works that he wanted to issue under the Attucks label.While Attucks continued to put out a few works with Bert Williams as their primary promotional vehicle, finding top-notch material not already contracted by other publishers was a challenge, including any of Shepard's existing works. He did manage another Alex Rogers number titled Nobody, which eventually became one of William's signature numbers, and is still well-known more than a century later. However, it was not published for several months, and would not by issued the Attucks company. Debts started to mount, and in July of 1905 an action was filed against Attucks by the firm of House, Grossman & Vorhaus for $301.61, presumably for services rendered. This and other challenges possibly proved to be too much for Shep, as two months prior, in May of 1905, he had agreed to a consolidation with the Gotham Music Company, which was already better situated at No. 42 West 28th Street in Tin Pan Alley (previously occupied by Harry Von Tilzer), creating Gotham-Attucks Music by mid-July. In short, it was a buy-out of his firm in order to acquire his carefully chosen existing properties. In later years Shep claimed it had been valued at $55,000, but no such price was reported in the trades, and was quite unlikely. In any case, Edmonds handed over a company that, in spite of the bumps, had already gained a good reputation and a fairly solid business model on which to build. The major problems still attached to the growing company had to do more with race and the bullying tactics of larger publishers than any other inhibiting factors.

Gotham Music Company - A Thorny Beginning

Similarly challenged by the music business, but for additional reasons that went beyond his skin color, composer Will Marion Cook was the reason that Gotham Music had been set up, as well as to accommodate his recently acquired friend and co-writer, Richard Cecil McPherson. While it was formed just weeks after Attucks had their official debut, and had its share of startup troubles, the approach to how the business was run was quite different in many regards.

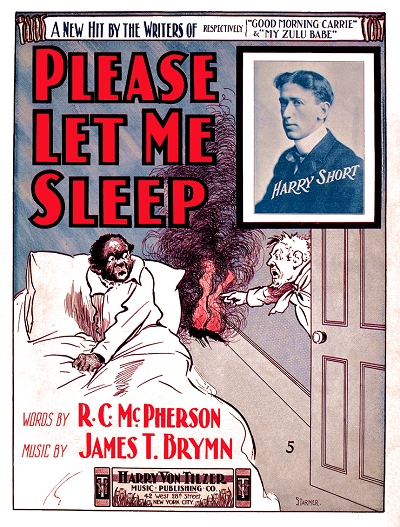

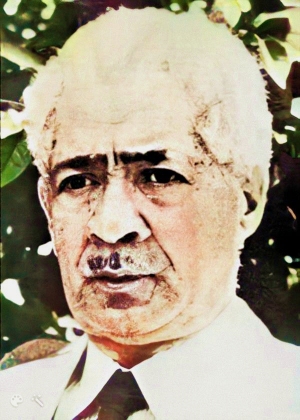

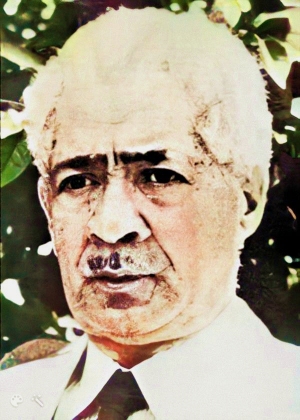

The birth year given for McPherson has gone through a number of variants over the years, with 1883 being the most common citation. However, the 1880 census showing him to be nine some seven months before his next birthday clearly suggests that not only was he alive well before 1883, but actually born as early as 1871, 1872 at the latest. For a number of reasons concerning his early movements, any birth year after 1875 (as he listed in the 1900 census) would make less sense. The mathematically suggested year of 1872 will be accepted for this essay as the most probable. Richard was one of two children born in Portsmouth, Virginia, to Henry McPherson and his wife Mary Louise, the other being his sister Eva (7/1882). The 1880 enumeration showed Henry to be a laborer, but within a few years he went into the undertaker business.

Richard was one of two children born in Portsmouth, Virginia, to Henry McPherson and his wife Mary Louise, the other being his sister Eva (7/1882). The 1880 enumeration showed Henry to be a laborer, but within a few years he went into the undertaker business.

Richard was one of two children born in Portsmouth, Virginia, to Henry McPherson and his wife Mary Louise, the other being his sister Eva (7/1882). The 1880 enumeration showed Henry to be a laborer, but within a few years he went into the undertaker business.

Richard was one of two children born in Portsmouth, Virginia, to Henry McPherson and his wife Mary Louise, the other being his sister Eva (7/1882). The 1880 enumeration showed Henry to be a laborer, but within a few years he went into the undertaker business.Richard's early education was from the Norfolk [Virginia] Mission School. Before he went for any advanced education, in February of 1891 at either age 17 or 18, Richard joined the Navy in Norfolk, likely as part of the support staff. His enlistment record showed him to be a waiter, and among his distinguishing marks he had "enlarged tonsils." After having saved up some money, he attended Norfolk Mission College in the mid-1890s, and then transferred to Lincoln University near Oxford, Pennsylvania, and Wilmington, Delaware, in 1898 or 1899. It was the first historically black university in the United States that granted accredited degrees. Richard also reportedly spent a semester at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School. He never obtained a degree from either institution. By this time Richard was spending his time away from the university in New York City, specifically trying to break into the music business. Among those that he made acquaintances with was vaudevillian Tom Lemonier, with whom he wrote some of his first songs.

The 1900 census creates a bit of a quandary in terms of identifying Richard. On June 2 he was enumerated at his parents' home near Norfolk, Virginia, but it is unclear if he was actually there or if that was what the enumerator was told. His mother, evidently suffering from a bout of vanity, gave her year of birth as 1872 (it was actually 1856), Eva's as 1883, and Richard - clearly added as an afterthought without any thought to logic - as 1880, making her eight at his time of birth. No career was listed for him, but Henry was shown to be an undertaker. On that same date in New York City, a Richard McPerson was also enumerated, black, born in Virginia, and working as a musician, living on 33rd street just blocks from what would soon be called Tin Pan Alley. This may be more of a coincidence than anything, since this Richard gave a birth year of 1870 but no month, and showed as married. The best and most accurate accounting of McPherson was actually his own, as he had taken on the job of enumerator for his section of Manhattan just off West 29th Street, where he was lodging. In that record, taken on June 12, he showed a November, 1875, birth, and his occupation was listed as a stenographer, which is logical, given that he had also been writing lyrics to Lemonier's music. In any case, he was clearly not 17 years of age as reported in many sources.

The best and most accurate accounting of McPherson was actually his own, as he had taken on the job of enumerator for his section of Manhattan just off West 29th Street, where he was lodging. In that record, taken on June 12, he showed a November, 1875, birth, and his occupation was listed as a stenographer, which is logical, given that he had also been writing lyrics to Lemonier's music. In any case, he was clearly not 17 years of age as reported in many sources.

The best and most accurate accounting of McPherson was actually his own, as he had taken on the job of enumerator for his section of Manhattan just off West 29th Street, where he was lodging. In that record, taken on June 12, he showed a November, 1875, birth, and his occupation was listed as a stenographer, which is logical, given that he had also been writing lyrics to Lemonier's music. In any case, he was clearly not 17 years of age as reported in many sources.

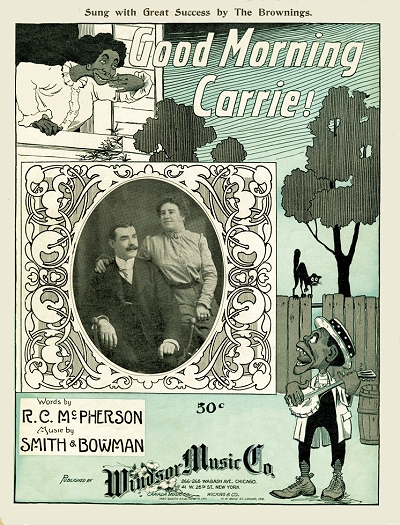

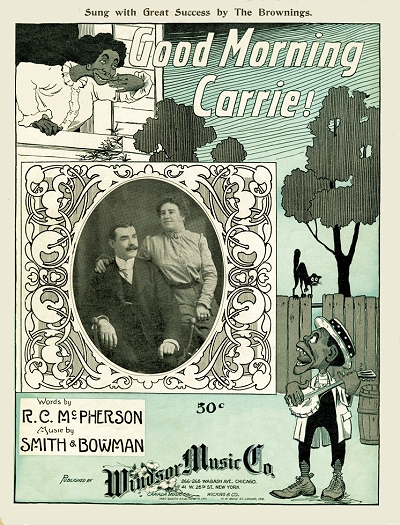

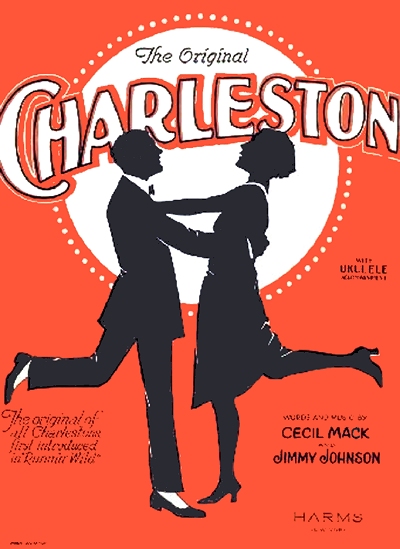

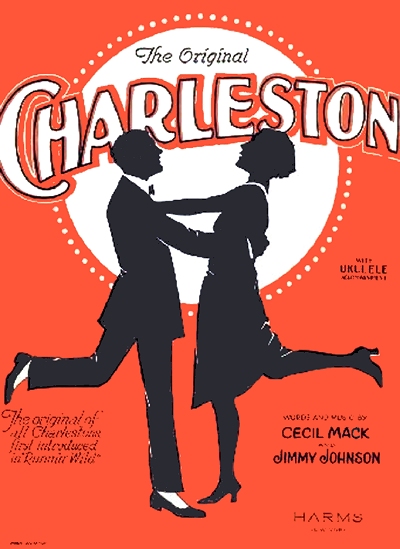

The best and most accurate accounting of McPherson was actually his own, as he had taken on the job of enumerator for his section of Manhattan just off West 29th Street, where he was lodging. In that record, taken on June 12, he showed a November, 1875, birth, and his occupation was listed as a stenographer, which is logical, given that he had also been writing lyrics to Lemonier's music. In any case, he was clearly not 17 years of age as reported in many sources.McPherson's earliest song collaborations were published by both Joseph Stern and the Shapiro, Bernstein and Von Tilzer firm in 1901, and were interpolated into the Bert Williams and George Walker show Sons of Ham. They did well enough that he abandoned his plans for a business or medical degree and entered the field of songwriting. His talent for subtle Negro dialect that did not perpetuate the stereotype of "coon songs" of the era helped to make his next number a lasting his. Good Morning, Carrie had music by Chris Smith and Elmer Bowman, and was among the first songs recorded by Williams and Walker in October of 1901. McPherson was quickly making friends with the other black songwriters in New York, and would collaborate with most of them in some way. It is very possible that one or more of them gave him his professional pseudonym, based on his middle name and part of his last, and by 1902 he was becoming known as Cecil Mack.

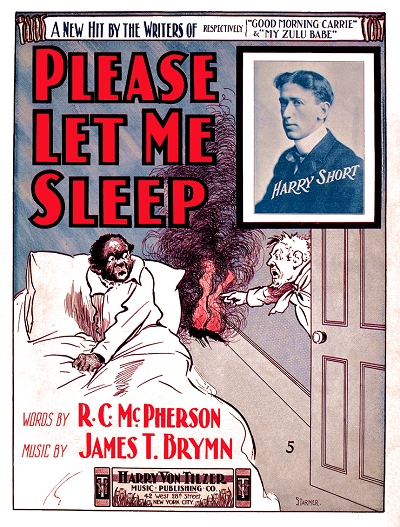

Among Mack's next hits were the comically clever Please Let Me Sleep composed with William and Walker's music director, Tim Brymn, and The Little Gypsy Maid, written with Harry B. Smith and Will Marion Cook, who had already been making waves in the music world. Brymn, born in 1875 in North Carolina, was a graduate of Shaw University, then New York's Charlton Conservatory School of Music, and was considered to be a first rate pianist and overall musician. Both he and Cook regarded Mack's lyric talent, and wrote more pieces with him over the next couple of years, including two that were part of Cook's groundbreaking In Dahomey musical score introduced in 1903. Then in 1904, as Cecil Mack, he co-wrote the megahit Teasing with the white composer and publisher brother of Harry Von Tilzer, Albert Von Tilzer. It was issued by Albert's own York Music Company, which provided Cecil with a connection that soon put him in the publishing business with no less than Will Cook and his brother John.

Will Marion Cook was born as William Mercer Cook into a life of at least some privilege in Washington, DC, in early 1869, less than four years after the end of the Civil War, and perhaps within a year of Scott Joplin (real birth date unknown). Both would prove to have similar musical aspirations, but the latter with a decidedly gentler approach. William was one of three brothers born to mulatto parents John H. Cook and Isabel "Belle" Hickman, the others being John H., Jr. (1867) and Oliver (1873). The 1870 census showed John, Sr., working as a clerk in the recently formed Freedmen's Bureau. A graduate of Oberlin College in Ohio, he would soon become the first dean of Howard University Law School following his graduation from that institution. Both Will's father and grandfather were musicians at some point, the latter being a slave fiddler on a Virginia plantation prior to the Civil War.

John died of tuberculosis in 1878. The 1880 census taken in DC showed the widowed Belle with her three children, also caring for her younger brother, sister, and sister-in-law, working as a teacher in the District of Columbia school system. As she had graduated with a music degree from the Oberlin College Conservatory in 1865, it is likely she taught music both publicly and privately, and did moderately well for her family at that. However, by 1881 the burden would prove to be more than she could manage.

|

The family was disbursed, and Will was sent to Chattanooga, Tennessee, to his grandparent's home for three years. While there he was taught to play the violin, or "fiddle," by his grandfather, and took to it with a near-obsessive zeal. In 1884 at the tender age of 15, Will was sent to live with an aunt in Oberlin, Ohio, and by 1886 was attending the music conservatory there, specifically to study violin in addition to music theory under Professor Amos Doolittle. His progress was such that Doolittle recommended to Belle that her son receive advanced training in Europe. While she was concerned about how to fund this expensive proposition, help came from no less than noted civil rights activist Frederick Douglass. He organized a fund-raising concert in Washington at the First Congregational Church in the summer of 1888, raising enough money to at least start Will on his way to Europe.

So it was that in the fall of 1888, Will Cook, now 19 and a full six feet in height (according to his passport), departed for Germany where he spent nearly two more years training at the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin, Germany, to study harmony, counterpoint, and violin under the esteemed Professor Joseph Joachim. In 1890, he came back to the United States where he made his public performance debut as a full-fledged virtuoso. That same year, Will took on the leadership of a chamber orchestra organized by Douglass, sending it on tour, and giving Cook a taste of leadership and ownership of his ability, and perhaps even some responsibility as a representative of the Negro race. Within another two years was composing serious works for violin and orchestra. By this time he had dropped Mercer from his name, adopting Marion instead.

Another boost to Will's growing ego came in 1893 when Douglass arranged to put him in charge of a musical event at the World's Columbian Exposition of that year held in Chicago. He was reported to have written an opera based on Harriet Beecher Stowe's controversial play Uncle Tom's Cabin. However, some of the updated content of Will's work made organizers uneasy, and it was dropped from the program. While he was in Chicago that August, any visits to the Exposition were likely as a guest, not a performer. As he was playing violin at various venues in Chicago during that month, it is probable that he got some exposure to the early stirrings of ragtime melodies and cakewalks.

As he was playing violin at various venues in Chicago during that month, it is probable that he got some exposure to the early stirrings of ragtime melodies and cakewalks.

As he was playing violin at various venues in Chicago during that month, it is probable that he got some exposure to the early stirrings of ragtime melodies and cakewalks.

As he was playing violin at various venues in Chicago during that month, it is probable that he got some exposure to the early stirrings of ragtime melodies and cakewalks.It is important to note that Cook took both his music and himself very seriously, and to that end perhaps felt some entitlement to be recognized for his abilities alone, instead of how good he was for his race. He also, at this point, did not appear to be leaning toward a career in popular music composition. However, that attitude either changed, or simply emerged by the mid-1890s, as the Cakewalk was coming to the fore; the harbinger of a new kind of music that was on the horizon. It was music of his race, but also music with the potential to be elevated to a new level, and to be used as a means to get himself more exposure as a serious composer.

Having met Negro baritone Harry T. Burleigh while performing at a classical concert in Chicago, Will was encouraged to go to New York City the following year where Burleigh placed him in the sights of another serious musician. It was there that Will spent some time learning from Czech composer Antonin Dvorak at his National Conservatory of Music. Cook did not regard Dvorak all that highly, and ended up studying under Professor John White at the same school for much of the year. He then joined the traveling stock company of Bob Cole for a season. Hired as their composer for special material, Cook had similar disdain for Cole, but for opposite reasons, as he saw Dvorak as too musically pompous and Cole as too musically unsophisticated. The feud between Cook and Cole would continue for some time after he left the company to play for the concert stage instead. During this period he had his earliest songs published in Washington, DC.

There was, according to a later account by composer and bandleader Edward "Duke" Ellington, an incident that possibly tipped the scales for the increasingly frustrated musician. After Will played an 1896 solo concert in the esteemed venue of Carnegie Hall (although several possible venues have been suggested by others), a New York reviewer wrote that Cook was definitely "the world's greatest Negro violinist," Cook reportedly responded with his characteristic indignant temper:

Dad Cook took his violin and went to see the reviewer at the newspaper office. "Thank you very much for the favorable review," he said. "You wrote that I was the world's greatest Negro violinist." "Yes, Mr. Cook," the man said, "and I meant it. You are definitely the world's greatest Negro violinist." With that, Dad Cook took out his violin and smashed it across the reviewer's desk. "I am not the world's greatest Negro violinist," he exclaimed. "I am the greatest violinist in the world!" He turned and walked away from his splintered instrument, and he never picked up a violin again in his life.

Even though he actually did play it on a few more select occasions, as noted at times in the newspapers over the next two decades, Will largely turned away from the violin around that time, studied more harmony and counterpoint, and set out to be recognized in a more permanent way than the occasional concert could do. To help him in that regard, Cook found one of the more interesting poets of color and of negro dialect, one who was known by many around the country, Paul Laurence Dunbar.

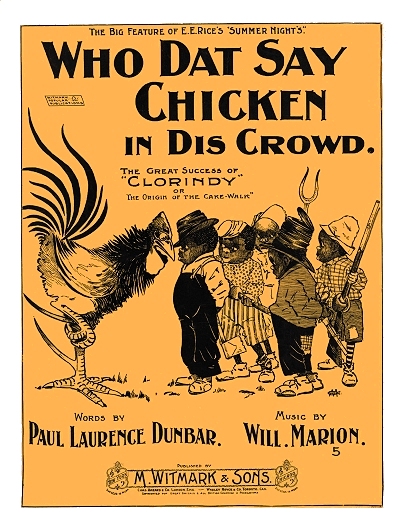

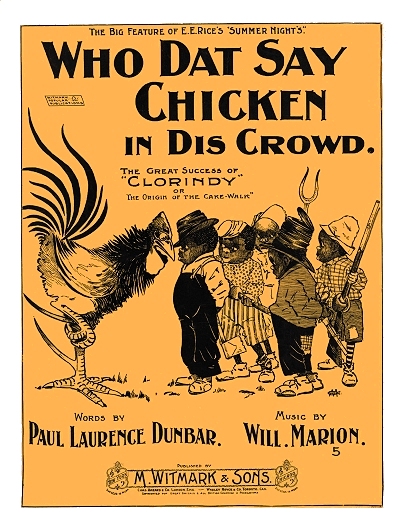

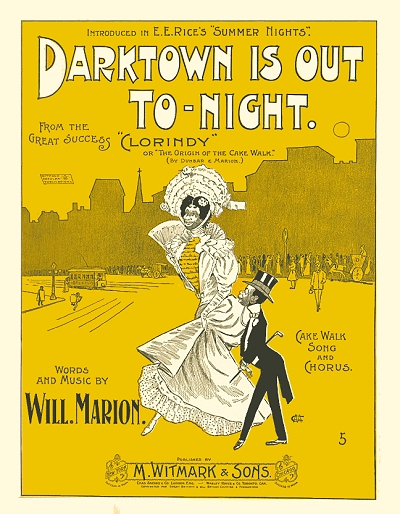

It was allegedly in one ten-hour session that Cook and Dunbar set out to conquer the serious musical stage. The end result was Clorindy: The Origin of the Cakewalk. Two things emerged from this union of the two men. First was a brilliant work that evoked many Negro themes while advancing their cause through carefully crafted libretto and music. The second was a reinforcement of a reputation that Will was quickly earning as a difficult and unpleasant individual to work with. It should be noted that it was staged on a rooftop theater, rather than on an indoor stage, as the owners of the theaters in Manhattan were not yet ready to "legitimize" a Negro production in a proper venue. Cook managed to cajole his way into a forced audition at the Casino Theater Roof Garden, which was reluctantly accepted with some insistence from the Garden's orchestra leader, John Braham. It opened in early July with leading Negro singer Ernest Hogan as the star.

Overall, Clorindy was a success during the 1898 season, albeit mostly with its expected target audience, which were the blacks of New York City. It received fine reviews in mainstream papers as well, so managed to hook in some curious white theater-goers and those with an interest in the music itself. In spite of the good reviews, Cook's musically educated mother was evidently nonplussed with Clorindy. She reportedly cried after hearing it, lamenting her son's evident turnabout from high classical to low popular music forms, saying to him, "I've sent you all over the word to study and become a great musician, and return such a nigger!" This both hurt and inspired him to elevate the status of Negro music by infusing it with classical music ideals and paradigms, making it more sophisticated while not denying the source material as coming from his race.

This both hurt and inspired him to elevate the status of Negro music by infusing it with classical music ideals and paradigms, making it more sophisticated while not denying the source material as coming from his race.

This both hurt and inspired him to elevate the status of Negro music by infusing it with classical music ideals and paradigms, making it more sophisticated while not denying the source material as coming from his race.

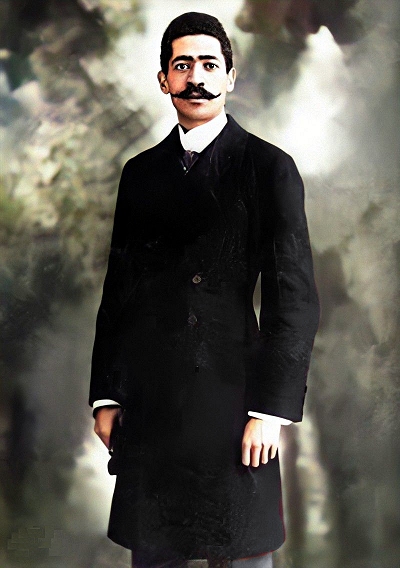

This both hurt and inspired him to elevate the status of Negro music by infusing it with classical music ideals and paradigms, making it more sophisticated while not denying the source material as coming from his race.Some of the pieces from Clorindy were published. In fact, it was Isadore Witmark who, as Witmark later recalled, was approached by Cook about a month before the work was debuted asking for the publisher's assistance with getting it staged in exchange for publication rights and all of the royalties. Witmark agreed to help, but also insisted that Cook keep the royalties. However, Cook told a different story, saying that Witmark informed him that he was perhaps delusional to think that any audience on Broadway (or on a rooftop above it) would be interested in hearing Negroes sing in a professional production, much less buy the music afterwards. The truth lay somewhere in between those two accounts, and the sheet music was a moderate seller, most notably helped by the song Who Dat Say Chicken in Dis Crowd.

Undaunted by criticism and emboldened by success, Cook followed Clorindy with the "one act operetto" [sic] Jes' Lak White Fo'ks. As with Clorindy it was largely a Negro story, but with Cook's own libretto for the most part, which pushed forth his own political and social agenda. Staged in 1899 it did not do very well, creating friction between Will and pretty much anybody who criticized the work. Among his most vocal critics was Bob Cole, who had enjoyed some success as a songwriter up to that time. In spite of that success, Cook had evidently found many opportunities during his time with Cole's stock company to belittle his employers work as the product of a limited Southern musical education. This did not help his relationship with Dunbar either. When Will realized that he needed Dunbar's help to retool Jes' Lak White Fo'ks with a better libretto, he evidently asked writer James Weldon Johnson to broker a deal between the two. According to Johnson in his autobiography:

...Cook persuaded me to use my good offices to have Dunbar collaborate with him another piece, a full-length opera to be called The Cannibal King... For Jes Lak White Folks... Cook wanted Dunbar's touch and, still more, his name again. But the great success of the first piece was not due along to Dunbar, nor was the partial failure of the second piece due alone to Cook. In Clorindy, New York had been given its first demonstration of the possibilities of Negro syncopated music, of what could be done with it in the hands of a competent and original composer. Cook's music, especially his choruses and finales, made Broadway catch its breath. In Jes Lak White Folks, the book and lyrics were not so good, nor was the cast; and, naturally, the music was not such a startling novelty. I did my best to persuade Paul to do the book and lyrics for The Cannibal King, but he was obdurate. He told me with emphasis, "No, I won't do it. I just can't work with Cook; he irritates me beyond endurance." Finally, I undertook the work of writing the lyrics, and actually got Cook to agree to have Bob Cole do the book... The Cannibal King was never wholly completed. Enough was finished, however, to enable Cook to negotiate a sale to a producer for a flat cash price that gave us several hundred dollars apiece. This was my first work with Cook; later, through the years, we wrote a number of songs in collaboration.

The Cannibal King opened in London in mid-1899 to mixed reviews, then in the United States. Through this work, and the growing reputation of Clorindy, Cook managed to garner growing respect in the musical world at large, but remained at odds with some of his peers, many of whom he clearly looked down upon for the role in perpetuating "coon songs" and lower forms of theater with base Negro dialects. He was engaged for another small set of songs with different lyricists that were interpolated into a 1900 production of The Casino Girl. There were some misfires over the next couple of years, and a few minor song hits penned with some of Will's allegedly reticent but tolerant peers, including Harry Smith and Cecil Mack. With them he wrote The Little Gypsy Maid, interpolated into a production of The Wild Rose in 1902. Most of the pieces were published by Von Tilzer, Shapiro or Witmark, whose professional managers helped to interpolate songs by Cook and Mack into other productions of the period. This also put him into the field of vision of Williams and Walker, as well as introduced a young lady singer named Abbie Mitchell. In reality, Abbie was his wife, the couple having married in 1899.

many of whom he clearly looked down upon for the role in perpetuating "coon songs" and lower forms of theater with base Negro dialects. He was engaged for another small set of songs with different lyricists that were interpolated into a 1900 production of The Casino Girl. There were some misfires over the next couple of years, and a few minor song hits penned with some of Will's allegedly reticent but tolerant peers, including Harry Smith and Cecil Mack. With them he wrote The Little Gypsy Maid, interpolated into a production of The Wild Rose in 1902. Most of the pieces were published by Von Tilzer, Shapiro or Witmark, whose professional managers helped to interpolate songs by Cook and Mack into other productions of the period. This also put him into the field of vision of Williams and Walker, as well as introduced a young lady singer named Abbie Mitchell. In reality, Abbie was his wife, the couple having married in 1899.

many of whom he clearly looked down upon for the role in perpetuating "coon songs" and lower forms of theater with base Negro dialects. He was engaged for another small set of songs with different lyricists that were interpolated into a 1900 production of The Casino Girl. There were some misfires over the next couple of years, and a few minor song hits penned with some of Will's allegedly reticent but tolerant peers, including Harry Smith and Cecil Mack. With them he wrote The Little Gypsy Maid, interpolated into a production of The Wild Rose in 1902. Most of the pieces were published by Von Tilzer, Shapiro or Witmark, whose professional managers helped to interpolate songs by Cook and Mack into other productions of the period. This also put him into the field of vision of Williams and Walker, as well as introduced a young lady singer named Abbie Mitchell. In reality, Abbie was his wife, the couple having married in 1899.

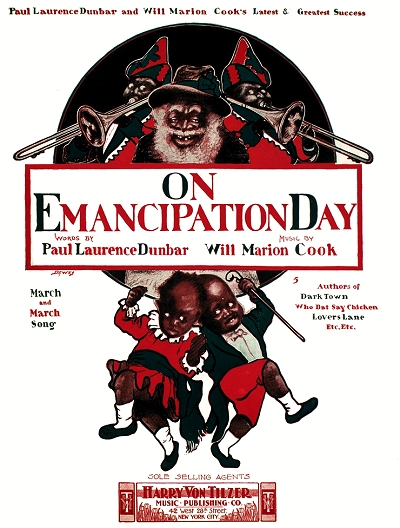

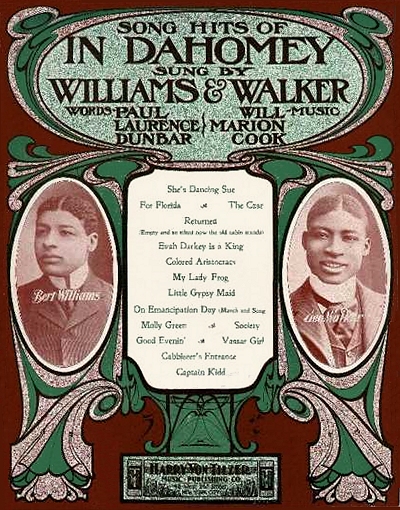

many of whom he clearly looked down upon for the role in perpetuating "coon songs" and lower forms of theater with base Negro dialects. He was engaged for another small set of songs with different lyricists that were interpolated into a 1900 production of The Casino Girl. There were some misfires over the next couple of years, and a few minor song hits penned with some of Will's allegedly reticent but tolerant peers, including Harry Smith and Cecil Mack. With them he wrote The Little Gypsy Maid, interpolated into a production of The Wild Rose in 1902. Most of the pieces were published by Von Tilzer, Shapiro or Witmark, whose professional managers helped to interpolate songs by Cook and Mack into other productions of the period. This also put him into the field of vision of Williams and Walker, as well as introduced a young lady singer named Abbie Mitchell. In reality, Abbie was his wife, the couple having married in 1899.Cook's first major success came in 1903 with In Dahomey. Written and copyrighted in 1902 with a book by Shephard Edmonds and lyrics once again by Dunbar, with Williams and Walker as the stars, it couldn't help but succeed with the best of black talent that New York had to offer. In Dahomey also overall has been viewed historically as the first black-written and produced music to rival similar white productions of the New York stage. The combination of operetta structure with ragtime music resonated with white audiences as well, and the production was regarded as substantial enough that it was the first major black-originated musical to be given an indoor stage on which to play. At that, one of the more popular pieces of the show was an interpolated number written by Alex Rogers, who was already an important part of Cook and Mack's world. Another piece written by Cook with scant lyrics by Dunbar was On Emancipation Day, essentially a cakewalk with lyrics added into the trio section. The show would ultimately play in New York, London, and on tour for the next four years. It also was the first major production to have the majority of its score published. However, it was issued by a British publisher, rather than one in New York, a situation which incensed Cook and set up a circumstance that would change the world of publishing for black composers and performers.

Will's brother John had also come to New York, and in 1904 saw an opportunity to help out his older brother and perhaps make some money in the process. Given Will's uneven temperament and his tenuous relationship with publishers and producers, he and some of his peers were clearly not getting the best possible deal for royalties or buyouts, particularly for hit shows. So John formed his own publishing company in the heart of Tin Pan Alley at 42 West 28th Street, which was also the current address for Harry Von Tilzer's company, and very near Albert Von Tilzer's distribution firm. Over the next several months of 1904, John published songs that were all by Will, including three from his next production, The Southerners, with lyrics by Harry Smith as Richard Grant.

However, the perception of John Cook's company as a vanity label for his brother was correct, and he sought to change that by expanding the scope and the stable of composers associated with him. Among them was Cecil Mack (McPherson), who had managed to work successfully with Will. So in February of 1905 John incorporated his firm for $10,000 as Gotham Music, with Will as the primary director, McPherson as a partner (and the major financial contributor at the beginning), and club owner Barron D. Wilkins, who owned several black cabarets and bars in the Tenderloin district of New York, and also provided some solid financial backing and a presence the banks would be willing to work with. Among their first issues in their short life were two Bert Williams songs with lyrics by Earle C. Jones, as well as relabeled sheets of the songs from The Southerners. They added several more pieces, but in a haphazard fashion, with many of them lacking the quality found in Edmond's repertoire under his Attucks insignia.

Among them was Cecil Mack (McPherson), who had managed to work successfully with Will. So in February of 1905 John incorporated his firm for $10,000 as Gotham Music, with Will as the primary director, McPherson as a partner (and the major financial contributor at the beginning), and club owner Barron D. Wilkins, who owned several black cabarets and bars in the Tenderloin district of New York, and also provided some solid financial backing and a presence the banks would be willing to work with. Among their first issues in their short life were two Bert Williams songs with lyrics by Earle C. Jones, as well as relabeled sheets of the songs from The Southerners. They added several more pieces, but in a haphazard fashion, with many of them lacking the quality found in Edmond's repertoire under his Attucks insignia.

Among them was Cecil Mack (McPherson), who had managed to work successfully with Will. So in February of 1905 John incorporated his firm for $10,000 as Gotham Music, with Will as the primary director, McPherson as a partner (and the major financial contributor at the beginning), and club owner Barron D. Wilkins, who owned several black cabarets and bars in the Tenderloin district of New York, and also provided some solid financial backing and a presence the banks would be willing to work with. Among their first issues in their short life were two Bert Williams songs with lyrics by Earle C. Jones, as well as relabeled sheets of the songs from The Southerners. They added several more pieces, but in a haphazard fashion, with many of them lacking the quality found in Edmond's repertoire under his Attucks insignia.

Among them was Cecil Mack (McPherson), who had managed to work successfully with Will. So in February of 1905 John incorporated his firm for $10,000 as Gotham Music, with Will as the primary director, McPherson as a partner (and the major financial contributor at the beginning), and club owner Barron D. Wilkins, who owned several black cabarets and bars in the Tenderloin district of New York, and also provided some solid financial backing and a presence the banks would be willing to work with. Among their first issues in their short life were two Bert Williams songs with lyrics by Earle C. Jones, as well as relabeled sheets of the songs from The Southerners. They added several more pieces, but in a haphazard fashion, with many of them lacking the quality found in Edmond's repertoire under his Attucks insignia.Among the nearly-instant troubles faced by Gotham were challenges from other publishers about existing material that the new company allegedly had purloined or to which they did not have a proper claim. In April of 1905, that included the song with a potential hit status, Let's Play a Game of Soldiers, written by Joseph T. Quirk and David Rose while Quirk was allegedly in the employ of publisher Will Haskins. After Haskins reportedly passed on the song and parted ways with Quirk, the latter went directly to McPherson and his new company with the song, giving full disclosure of the circumstances, but noting that it had not been copyrighted. So after Gotham obtained legal copyright, Haskins had them enjoined so they could not issue the piece he had just passed on, and asked for $10,000 in damages. Ultimately Haskins, who had already taken out advertisements on the piece in the trades, did not get much of what he was looking for, but neither did Gotham as the song was only tepid seller with the public.

Less than four months in by the end of May, having already been dealt blows by court troubles and the lack of a clear hit to generate revenue, Gotham was looking to raise their profile a bit. They had good writers under contract, as did Attucks, but these writers also had contracts with theatrical companies who in turn were already set with Stern, Witmark, and other large firms. So when Shep Edmonds was looking to uncomplicate his life and turn a small profit, and Gotham was looking for that profitable property, it appears that Nobody and other select pieces were enticing enough for McPherson, Cook and company to go forward with a merger/acquisition. It was announced in the New York papers on May 28, 1905, that, "The Gotham Music Company and the Attucks Music Company have consolidated and shall hereafter operate under the firm name of the Gotham-Attucks Music Company." By late July the ink was dry and they were in business, as per several notices in the music trades. But for how long and to what end?

Gotham-Attucks Music Company - The House of Melody

One of the first things that McPherson did to bolster the company, and perhaps to help fund and fight the accumulative lawsuits which eventually were dismissed or found to be in their favor, was to secure the best possible black talent to commit to the Gotham-Attucks brand. To that end, one of the early announcements was that Bert Williams and George Walker would be staff writers for the firm. Walker, who was more or less a stage talent but not a material contributor to the music, did not have much more to offer to the firm than his name. Williams, however, did write a few pieces, a couple of them rather significant, that were published by Gotham-Attucks. Mack tried to acquire other talent as well, including Alex Rogers and Chris Smith, but in doing so he discovered the same conundrum that his predecessor Shep had faced - that of time spent as an administrator rather than as a musician. So in most of his first year at the helm of Gotham-Attucks, Cecil Mack found little or no time to contribute to any compositions.

The 1905 New York State census showed Shep Edmond and his wife Annie residing in Manhattan along with a butler, showing some sign of personal prosperity due to his prior earnings. The same enumeration showed McPherson, listed as a songwriter, living with his aunt Georgie Avendorth on 29th Street, just a couple of blocks from his new office. Will Cook and Abbie Mitchell were residing in Manhattan for that record with their daughter Marion (1900) and son William Mercer (1903), as well as Will's aunt Isabella Howard. Both of them were listed as musicians.

The same enumeration showed McPherson, listed as a songwriter, living with his aunt Georgie Avendorth on 29th Street, just a couple of blocks from his new office. Will Cook and Abbie Mitchell were residing in Manhattan for that record with their daughter Marion (1900) and son William Mercer (1903), as well as Will's aunt Isabella Howard. Both of them were listed as musicians.

The same enumeration showed McPherson, listed as a songwriter, living with his aunt Georgie Avendorth on 29th Street, just a couple of blocks from his new office. Will Cook and Abbie Mitchell were residing in Manhattan for that record with their daughter Marion (1900) and son William Mercer (1903), as well as Will's aunt Isabella Howard. Both of them were listed as musicians.

The same enumeration showed McPherson, listed as a songwriter, living with his aunt Georgie Avendorth on 29th Street, just a couple of blocks from his new office. Will Cook and Abbie Mitchell were residing in Manhattan for that record with their daughter Marion (1900) and son William Mercer (1903), as well as Will's aunt Isabella Howard. Both of them were listed as musicians.Cook spent much of that year performing at the piano, and perhaps consulting with his new company, rather than writing. Late in the year, however, Will was busy once again, having written much of the music for his comic opera Abyssinia to a book and lyrics collectively by Bert Williams, Alex Rogers and Jesse Shipp. Debuting in the midst of the winter of 1906, initial reviews of Abyssinia were tepid, with the New York Morning Telegraph of February 21, 1906 insisting that it was "Far From a Hit," and "Devoid of the True Negro Spirit." Reviewer Irving Lewis, without overtly saying so, inferred that it was simply not black enough, or perhaps even racial enough.

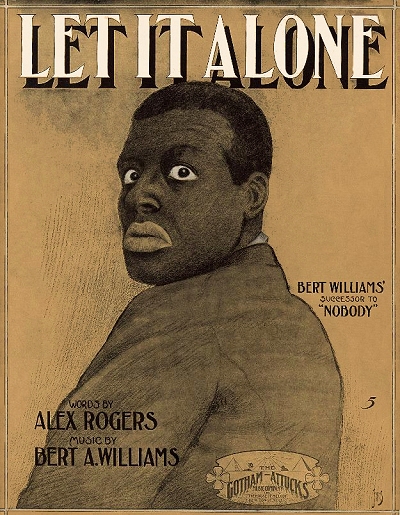

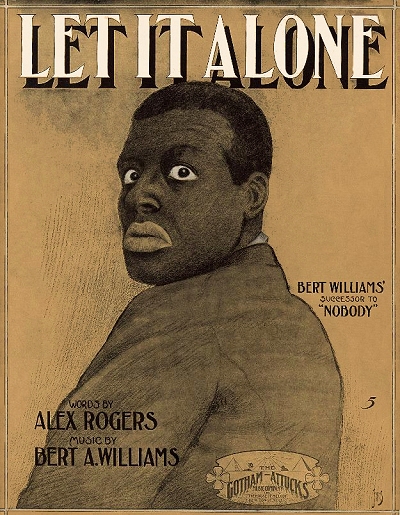

Having managed to take care of the initial lawsuits pending when the company was merged, Gotham-Attucks forged forward into 1906, but with little participation by Shep Edmonds who turned around and self-published a couple more of his own works. Mack teamed with Smith again, and over the next several years they would turn out a variety of clever songs that did moderately well. However, even with Albert Von Tilzer's assistance, they did not get the distribution necessary to take most of their material to a national stage. Their big hit for 1906 was He's a Cousin of Mine, which was taken up by the particular but even-handed Marie Cahill in her show Marrying Mary. Williams and Walker were among their best allies, and they recorded the Mack/Smith number All In, Down and Out from the musical Abyssinia that same year. Williams and Rogers came up with a successor to Nobody titled Let it Alone, but as it was a property suited to Bert's unique delivery, it had limited success for the firm.

In late 1905 and into 1906, Cook had presented his Tennessee Students (originally the Memphis Students) ensemble act in New York. In late 1906 into 1907 they repeated the act in Europe, then in the US at the Victoria Roof venue, followed by a short run at Hammerstein's. The show starred Ernest Hogan as well as Abbie Mitchell. Cook and his wife had worked together for some time, and even though it was not widely publicized for many years, the word was out that the two had been married for several years. As to her particular level of talent, an early 1907 review of Tennessee Students helped to give a measure of depth to it in a short description:

Abbie Mitchell, who heads the act, uses good judgment throughout in confining herself to the simple ballads. Hers is a voice of evident training, but she avoids the common mistake of seeking to display its technical brilliancy at the expense of simplicity.

The increasingly frustrated Cook, who at times made quite clear his view of poor race relations within the publishing business, may have felt targeted when at the end of January Gotham-Attucks faced yet another legal challenge. The firm of May & Harris, representing small publisher Morris Music, put legal rights to the moderate hit song He's a Cousin of Mine into receivership, claiming that they had sold a share of the piece to Gotham-Attucks, rather than an outright sale. The negative publicity did not help, as they kept referring Gotham-Attucks as a "colored" firm or one run by "colored managers." Then things escalated for Cook personally in February when he was fined $150 by the manager of Tennessee Students when the show went to Boston, but his wife Abbie instead sailed for the Wintergarten in Berlin, Germany, as she had allegedly not been contractually obligated to take the tour. The indignant and obstinate Cook not only vowed to the press that he would get back the $150, but that he would ask for an extra punitive $5,000 "as a balm."

The firm of May & Harris, representing small publisher Morris Music, put legal rights to the moderate hit song He's a Cousin of Mine into receivership, claiming that they had sold a share of the piece to Gotham-Attucks, rather than an outright sale. The negative publicity did not help, as they kept referring Gotham-Attucks as a "colored" firm or one run by "colored managers." Then things escalated for Cook personally in February when he was fined $150 by the manager of Tennessee Students when the show went to Boston, but his wife Abbie instead sailed for the Wintergarten in Berlin, Germany, as she had allegedly not been contractually obligated to take the tour. The indignant and obstinate Cook not only vowed to the press that he would get back the $150, but that he would ask for an extra punitive $5,000 "as a balm."

The firm of May & Harris, representing small publisher Morris Music, put legal rights to the moderate hit song He's a Cousin of Mine into receivership, claiming that they had sold a share of the piece to Gotham-Attucks, rather than an outright sale. The negative publicity did not help, as they kept referring Gotham-Attucks as a "colored" firm or one run by "colored managers." Then things escalated for Cook personally in February when he was fined $150 by the manager of Tennessee Students when the show went to Boston, but his wife Abbie instead sailed for the Wintergarten in Berlin, Germany, as she had allegedly not been contractually obligated to take the tour. The indignant and obstinate Cook not only vowed to the press that he would get back the $150, but that he would ask for an extra punitive $5,000 "as a balm."

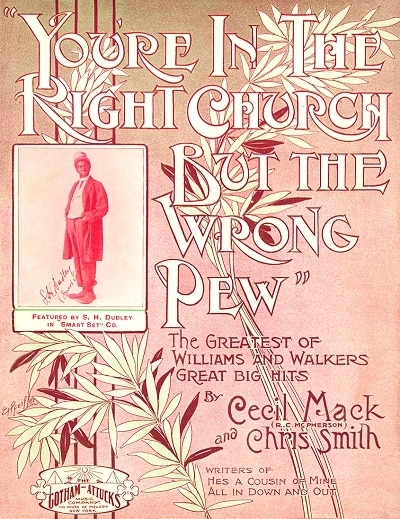

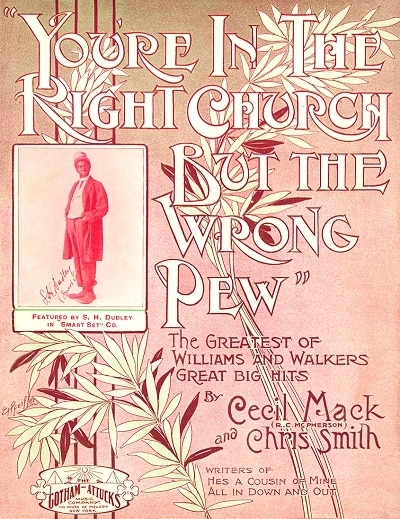

The firm of May & Harris, representing small publisher Morris Music, put legal rights to the moderate hit song He's a Cousin of Mine into receivership, claiming that they had sold a share of the piece to Gotham-Attucks, rather than an outright sale. The negative publicity did not help, as they kept referring Gotham-Attucks as a "colored" firm or one run by "colored managers." Then things escalated for Cook personally in February when he was fined $150 by the manager of Tennessee Students when the show went to Boston, but his wife Abbie instead sailed for the Wintergarten in Berlin, Germany, as she had allegedly not been contractually obligated to take the tour. The indignant and obstinate Cook not only vowed to the press that he would get back the $150, but that he would ask for an extra punitive $5,000 "as a balm."In the end, Cook got his $150, and the action against Gotham-Attucks was decided in their favor for He's a Cousin of Mine, but both of these fights required energy and money, which resulted in little net gain. Cook, Shipp, Rogers and Williams came out with another successful musical later in the year, Bandanna Land. However, another continuing challenge in the company's efforts to remain vital came from established practices and alliances between theatrical producers and key publishers of Tin Pan Alley, which inhibited them from acquiring or retaining material. Cecil Mack and James Reese Europe wrote a score for Gus Hill in 1907 titled The Black Politician, starring the increasingly favored comedian Sherman H. Dudley. This was the first complete score that Mack had been involved with, and presented a good opportunity for Europe, who would soon have a prestigious command of sorts over the black musicians of New York. However, Mack's own firm was not able to get publication rights for his own work, as Hill had engaged Will Rossiter, "The Chicago Publisher," to take on at least five of the pieces, likely in exchange for some financial assistance with staging the production.

Even with their collective involvement, Williams, Smith, and even the difficult Cook, had standing contractual arrangements with other publishers and quotas to fill, so they could not always supply good content for their own concern.

Other black composers who were friends and associates of the directors ended up having nothing to offer Mack and his company, including Irving Jones, Bob Cole, Ernest Hogan, Al Johns, and their founding father, Shepard Edmonds. The result was an average of ten pieces per year issued by Gotham-Attucks, in contrast to the 150 to 2,000 publications put out annually by other Tin Pan Alley firms. Only the stalwart E.T. Paull was issuing less, but his reputation and colorful covers kept his firm profitable. The larger firms were also more enticing to black writers, since they had the resources and personnel to plug their works (although often by masking the race or gender of their writers) both to the public and to vaudeville and theatrical performers. The lack of profitability even made advertisements in trade papers or general newspapers difficult, and they often had to depend on plugs and announcements, as well as their promotional material on the back covers of Gotham-Attucks sheets.

|

While Bandanna Land offered some hope through minor hits that Mack was able to retain, in addition to an interpolation of Nobody for a second round of sales, the only notable piece from the production was the comically salacious Mack/Smith number, You're in the Right Church But the Wrong Pew. This helped to make 1908 a slightly better year, and they even felt confident enough to move from 28th street to a location closer to the major theaters, 136 West 37th Street. Another promotional vehicle was the formation of The Frogs (pictured left), founded by Williams and Walker, and made up of the leading black composers and performers of New York during that year, although with the conspicuous absence of independently-minded Will Cook. Mack was the first secretary of the organization, headed by George Walker and John Rosamond Johnson. While not directly beneficial to Gotham-Attucks, just the mention of the composers' names in the reports of various functions they held or appeared at was a peripheral form of publicity. They soon expanded the esteemed group to include professionals from other high-profile fields as well. Still, it was not quite enough to be of much help to the struggling firm.

Mack admitted to a trade paper in early 1909 that Gotham-Attucks was not doing as well as he had hoped, but that the best was yet to come. They had been actually giving away arrangements for band and orchestra, hoping that theatrical performances would turn into sales. (This practice plus that of professional copies was widely debated amongst publishers over the next several years, and eventually all but banned by most of them, who started charging even for samples.) Their forward progress was impeded by the virtual loss of one of their stars and best promoters, George Walker, who had spent the past decade on stage with Bert Williams. He had suffered from tertiary syphilis, and the disease wore him down to the point where he finally had to withdraw from Bandanna Land, and finally from any stage work. For a time, his wife, Aida Overton Walker, took over in his roles, singing the same hit songs. So they had to look elsewhere for their stars.

They had been actually giving away arrangements for band and orchestra, hoping that theatrical performances would turn into sales. (This practice plus that of professional copies was widely debated amongst publishers over the next several years, and eventually all but banned by most of them, who started charging even for samples.) Their forward progress was impeded by the virtual loss of one of their stars and best promoters, George Walker, who had spent the past decade on stage with Bert Williams. He had suffered from tertiary syphilis, and the disease wore him down to the point where he finally had to withdraw from Bandanna Land, and finally from any stage work. For a time, his wife, Aida Overton Walker, took over in his roles, singing the same hit songs. So they had to look elsewhere for their stars.

They had been actually giving away arrangements for band and orchestra, hoping that theatrical performances would turn into sales. (This practice plus that of professional copies was widely debated amongst publishers over the next several years, and eventually all but banned by most of them, who started charging even for samples.) Their forward progress was impeded by the virtual loss of one of their stars and best promoters, George Walker, who had spent the past decade on stage with Bert Williams. He had suffered from tertiary syphilis, and the disease wore him down to the point where he finally had to withdraw from Bandanna Land, and finally from any stage work. For a time, his wife, Aida Overton Walker, took over in his roles, singing the same hit songs. So they had to look elsewhere for their stars.

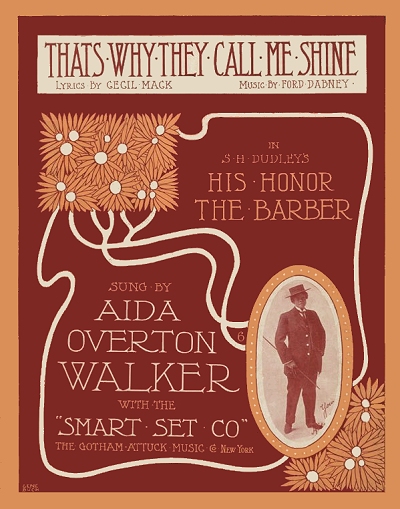

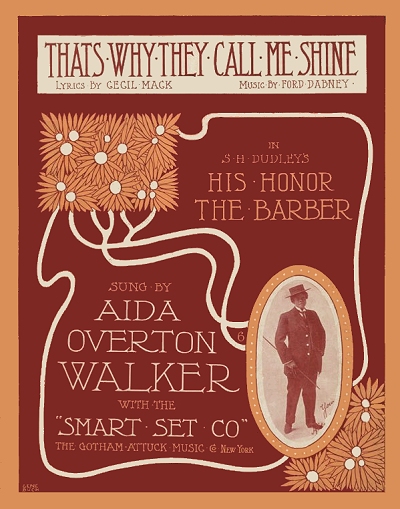

They had been actually giving away arrangements for band and orchestra, hoping that theatrical performances would turn into sales. (This practice plus that of professional copies was widely debated amongst publishers over the next several years, and eventually all but banned by most of them, who started charging even for samples.) Their forward progress was impeded by the virtual loss of one of their stars and best promoters, George Walker, who had spent the past decade on stage with Bert Williams. He had suffered from tertiary syphilis, and the disease wore him down to the point where he finally had to withdraw from Bandanna Land, and finally from any stage work. For a time, his wife, Aida Overton Walker, took over in his roles, singing the same hit songs. So they had to look elsewhere for their stars.Gus Hill produced another show in 1909 that was largely penned by Brymn and Smith, with some lyrics by Mack. His Honor the Barber presented them with the ongoing challenge of letting them issue their own material, as Hill offered many of the pieces to Joseph Stern, including the comical Come After Breakfast, Bring Your Own Lunch, and Leave Before Supper-Time. However, another lasting hit that would endure long after the death of its composers, Cecil and newcomer Ford Dabney, was That's Why They Call Me Shine, albeit in later years with less race-centric lyrics. Shine, which was sung in the show by George Walker's wife, Aida Overton Walker (filling in for her ailing spouse), was the major money-maker of 1910 for Gotham-Attucks, and helped to elevate Dabney as a competent composer. Both he and Europe had become the key directors of New York's stellar musical organization, The Clef Club. It was made up of all of the finest musicians of color from New York and surrounding areas, and through concerts they became known as the go-to source for the best possible music for events held by the richest of the rich, New York City's "400," comprised of the most prosperous New York families.

and through concerts they became known as the go-to source for the best possible music for events held by the richest of the rich, New York City's "400," comprised of the most prosperous New York families.

and through concerts they became known as the go-to source for the best possible music for events held by the richest of the rich, New York City's "400," comprised of the most prosperous New York families.

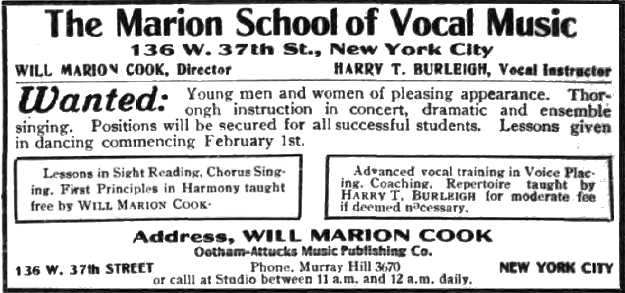

and through concerts they became known as the go-to source for the best possible music for events held by the richest of the rich, New York City's "400," comprised of the most prosperous New York families.In spite of the growing success of That's Why They Call Me Shine, it was clear that Gotham-Attucks could not survive on the income from just a few works. Even its most ardent champions were going elsewhere in order to make a respectable amount from their newest compositions, or at least see the distributed more effectively around the country. Smith and Williams were among the more evident defectors, and along with Smith at times was the company's director, Cecil Mack, who had to admit to the trouble in his firm. Regardless of the roles that Will and John Cook played in getting Gotham-Attucks launched, even Will had his latest 1910 hit, Lovie Joe, published by Harry Von Tilzer. These firms could count on volume, knowing that the occasional hit would counter any flat sales by other pieces, but Gotham-Attucks simply did not have that advantage.

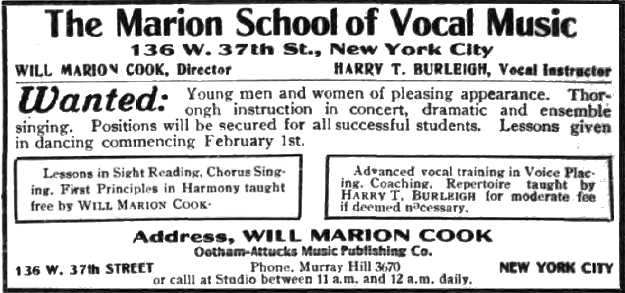

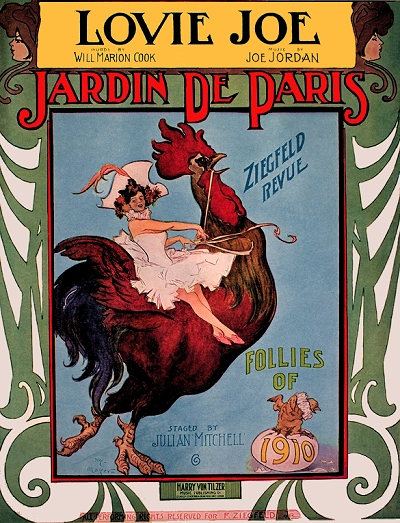

Will Cook was looking to supplement his income, so he used the firm as a base for a small school for students interested in learning vocal skills and drama. Cook was assisted by one of his few close friends who had encouraged him in the beginning, Harry Burleigh, who was the vocal instructor. They placed several advertisements in the black-oriented New York Age in late 1909 and early 1910, using the Gotham-Attucks building as the address. Mack also reached out beyond his own community, soliciting songs from white writers as well, including the lesser known at that time L. Wolfe Gilbert. But without the necessary resources to hire song pluggers or place copious newspaper advertisements, they just could not get the necessary traction to turn the average piece into even a moderate seller.

they just could not get the necessary traction to turn the average piece into even a moderate seller.

they just could not get the necessary traction to turn the average piece into even a moderate seller.

they just could not get the necessary traction to turn the average piece into even a moderate seller.The 1910 enumeration showed McPherson lodging not all that far from his office, and listed as a music publisher, albeit with more than a half-decade trimmed from his actual age. Will Marion Cook was now divorced, listed as a composer of music, and lodging with orchestra musician Daniel E. Murray He would work with Abbie on selected occasions over the next few years. She kept the children, although they were as much in the care of her parents as herself, as she had not yet given up the stage.

Cook was largely disengaged from Gotham-Attucks by 1911, but still very much in the news, and as obstinate as he had ever been, at times rightfully, concerning the view of him as a talented "colored" composer and musician. This attitude created a stir in November of 1910 when he sent a letter to the dramatic editor of the New York Age, reprinted an commented on in their February 9, 1911 issue, charging that colored composers and performers were being "discriminated against by several white music publishers. It also underscored his impending separation from his own publishing house.

A recent experience with a music publishing concern inspires me to comment on the treatment colored composers and artists received from some of these firms. As you now, for the past year all my songs have been published by the Harry Von Tilzer Publishing Company. Knowing this to be my headquarters many well-known colored writers, actors and singers have called on me at the Von Tilzer offices to consult about material either for use on the stage or in regard to having songs published [albeit evidently not by Gotham-Attucks].

The professional manager of the Von Tilzer Company, Max Winslow, after expressing disapproval of many of these visits by sour looks and evidences of lack of courtesy to my visitors, finally blankly informed me recently "that entirely too many spades come in the office."

Inasmuch as music of the day is to a great degree popularized by the colored performer and café singer, and inasmuch as the majority of music firms cater to the colored actor and singer when they have new songs, I feel that the color prejudice of Mr. Winslow should be widely known. I would suggest that since our singing of songs helps to popularize and increase the sale, that we seek those firms where our presence is not only welcomed but eagerly sought... I have often noticed and commented on the courtesy shown them at Remicks, Witmark's, Ted Snyders and others...

The editor generously noted that "Will Marion Cook is said to be somewhat erratic in his method of transacting business at times... yet his veracity has never been questioned." The issue was a legitimate one, and indeed, underscored the very reason that Gotham-Attucks had been formed in the first place. Yet in spite of their intent, the larger white-run firms simply dominated the music industry in New York. Prejudice still obviously existed, even progressive in New York City, but it was usually at the individual level rather than corporate. To that end, younger brother Will Von Tilzer responded to the charge in the February 23, 1911, issue of the New York Age, with no love lost for Cook, although voiced in a diplomatic fashion:

The writer wishes to state that the whole article is not only an injustice to the Harry Von Tilzer Music Publishing Company, but to all the colored writers and performers. The man who was instrumental in having the article printed to a great extent, his present opportunities to a member of the Barry Von Tilzer Music Publishing Company. he found plenty of encouragement here during the twelve months that this company entered to his needs.

We believe, as a paper catering to the colored people, you wish your readers to know the truth, and do not want to have them labor under the impression that has been conveyed to them by a man who is allowing personal prejudice to interfere with his better judgment...

If you will consult the representative performers and writers of your race, I believe you will easily be able to convince yourself that they have never lacked courteous treatment In the establishment of Harry Von Tilzer.

We are writing you this letter not because we are soliciting favors from anyone, but because, as stated above, we believe that there has been an injustice done your paper.

The editor lauded the efforts of Will Von Tilzer, yet noted that there was no denial of Max Winslow's role in the incident. This likely added a little bit of poison to the reputation of Cook among the major publishers, underscoring the very need for a firm like Gotham-Attucks, but his reputation as a musician and composer trumped the other concerns, so he rarely lacked for a publisher willing to take on his work. To that end, he was done with the experiment, and his defection, along with Smith, Williams, and others, imploded the efficacy of their firm.

McPherson, more or less the last surviving member of Gotham-Attucks, finally threw in the towel in mid-1911. Mack held a fire sale of the company's major copyrights, most of which went to a company he had done with business with for a decade, Joseph Stern. Remaining properties were later purchased by the Robbins-Engel firm. Both companies reissued songs like Shine and Nobody separately, but most of the rest of them in folios, generating at least minimum income, albeit not for their originators. Surprisingly, Mack and Wilkins did not simply dispose of the firm, but sold off the name and the office space to another investor looking for an existing property. In hindsight, it turned out to be an unfortunate move and created a less than respectable end to a firm that had been founded with good intentions and optimism just six years prior.

Gotham-Attucks under Ferdinand Mierisch

Ferdinand Mierisch may have started out as a well-intentioned publisher who was simply trying to give others a break, but his methodologies soon became and remain suspect to this day. He was one of two surviving children out of a total of six, born in June of 1874 in Brooklyn, New York, to German immigrants Herman and Fredericka Mierisch, the other child being his younger brother Charles (8/1876). The 1880 census showed Herman to possibly be a lamp lighter, but by 1900 he was listed as a porter. For that same record Ferdinand, still living with his family, was listed as an insurance agent. However, he had a musical side to him as well and would soon try to find a way to break into the business.

The 1880 census showed Herman to possibly be a lamp lighter, but by 1900 he was listed as a porter. For that same record Ferdinand, still living with his family, was listed as an insurance agent. However, he had a musical side to him as well and would soon try to find a way to break into the business.

The 1880 census showed Herman to possibly be a lamp lighter, but by 1900 he was listed as a porter. For that same record Ferdinand, still living with his family, was listed as an insurance agent. However, he had a musical side to him as well and would soon try to find a way to break into the business.

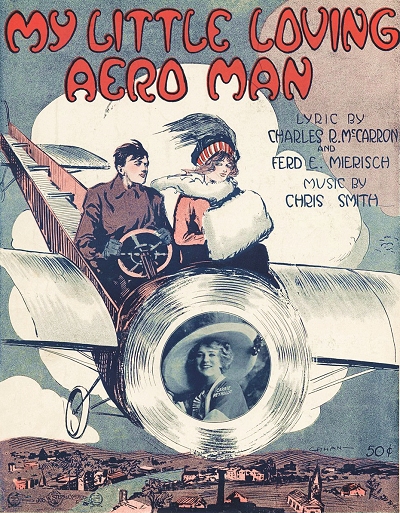

The 1880 census showed Herman to possibly be a lamp lighter, but by 1900 he was listed as a porter. For that same record Ferdinand, still living with his family, was listed as an insurance agent. However, he had a musical side to him as well and would soon try to find a way to break into the business.As a fledgling composer, Mierisch penned lyrics to a 1907 piece titled It Rivals the Great White Way, a song referring to Broadway by its nickname. The copyright showed music to be by the "Madden Music Co.," but likely referred to Edward Madden, who was known mostly as a lyricist, but had dabbled in music from time to time, and was considered by some to be an early "song shark." Then there was nothing from him for the next four years. The 1910 census showed Mierisch still living with his parents at age 35, and working in an undertaker's shop. However, opportunity soon presented itself, and Edward, finally finding a way to make money in music, pounced on it.