Will H. Dixon, while a lesser-known ragtime era composer, was still in the mix of one of the more important group of black musicians of the 1900s and 1910s in Chicago and New York City. Unfortunately, his demise came too early to allow him to shine in the 1920s, another casualty of the "sporting life" that took out way too many musicians of all backgrounds during that period. Will was one of nine children born to John Henry Dixon and Mary Putnam in West Virginia. As they had come from Maryland and Ohio respectively, they were likely not former slaves,

and West Virginia had been divided from Virginia in 1863 as a Northern (Union) State prior to reunification of the country. Of Will's eight siblings, only three made it beyond childhood, including John H., Jr. (4/1873), Harry E. (10/1885), and Estella "Stella" Mae (7/1889). The 1880 enumeration taken in Wheeling, West Virginia, where Will had been born nine months prior, showed the elder John to be a barber.

|

In their youth, Will and his younger siblings attended the segregated Lincoln School in Wheeling, which was responsible for teaching the children of color in both Ohio and Marshall counties. However, at some point in the 1890s, perhaps seeking better opportunities for the family, John and his brood relocated to Chicago, Illinois. It is probable that Will received instruction in music, particularly piano, harmony and theory, which made him a capable arranger and composer. It also instilled in him an appreciation for both popular music and some of the higher classical forms, as well as a love for theater. For the 1900 census, taken in the so-called "Bronzeville" sector of the south side of the city, John, Sr., was listed as a railroad brakeman, and John, Jr. held the same position. Either Will or the enumerator listed his occupation as "theatrical man."

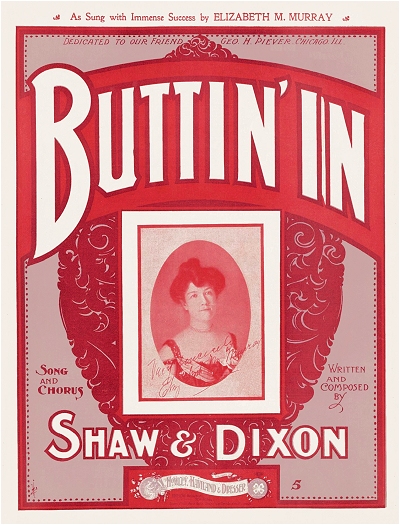

Will's involvement in the Chicago theater scene is partially obfuscated by a lack of information in traditional newspapers of the time. However, it is possible that he had had contributed a work to the Christian Evangelist periodical in 1901, showing him to be a budding writer through his poem Uncle Tobe's Thanksgiving, which may have been a potential song lyric. (This can also be discounted by the existence of two other Will H. Dixons from western Illinois, both White, who also had written lyrics.) By this time, Dixon had left home in hopes of making a living with his musical talent. His initial move was a foray into minstrelsy, shows based on either real or faux stereotypical black culture, which nonetheless provided a gateway into stage performance. His earliest tours were with Phil R. Miller's Hottest Coon in Dixie Company in late 1900. Within a year he was found in advertisements to be part of Rusco & Holland's Big Minstrel Festival Company, where he was featured as a singer, rather than just an end man (usually named Mr. Tambo or Mr. Bones) as was often the case with such talent. This allowed him to shine on his own, and drew further attention to his particular gifts, as highlighted in the occasional newspaper mention. It is also possible that teamed up with writer Arthur Sumner Shaw, and they created a musical play titled Buttin In that saw very little traction on its own. However, some of the numbers written for it got circulation in both Chicago through McKinley Music and New York through Howley, Haviland and Dresser.

Will's involvement in the Chicago theater scene is partially obfuscated by a lack of information in traditional newspapers of the time. However, it is possible that he had had contributed a work to the Christian Evangelist periodical in 1901, showing him to be a budding writer through his poem Uncle Tobe's Thanksgiving, which may have been a potential song lyric. (This can also be discounted by the existence of two other Will H. Dixons from western Illinois, both White, who also had written lyrics.) By this time, Dixon had left home in hopes of making a living with his musical talent. His initial move was a foray into minstrelsy, shows based on either real or faux stereotypical black culture, which nonetheless provided a gateway into stage performance. His earliest tours were with Phil R. Miller's Hottest Coon in Dixie Company in late 1900. Within a year he was found in advertisements to be part of Rusco & Holland's Big Minstrel Festival Company, where he was featured as a singer, rather than just an end man (usually named Mr. Tambo or Mr. Bones) as was often the case with such talent. This allowed him to shine on his own, and drew further attention to his particular gifts, as highlighted in the occasional newspaper mention. It is also possible that teamed up with writer Arthur Sumner Shaw, and they created a musical play titled Buttin In that saw very little traction on its own. However, some of the numbers written for it got circulation in both Chicago through McKinley Music and New York through Howley, Haviland and Dresser. |

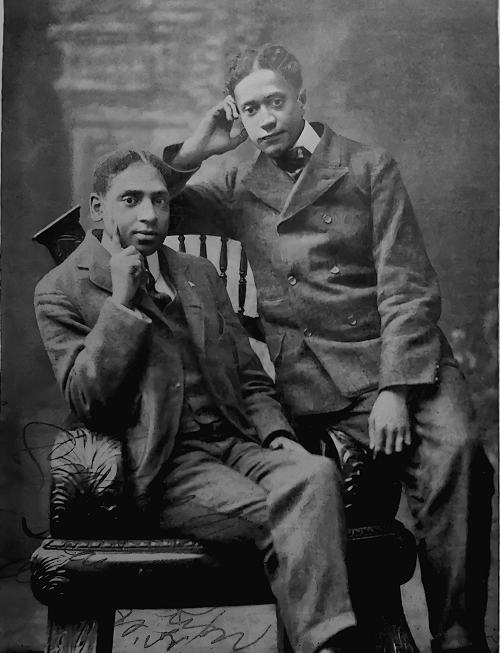

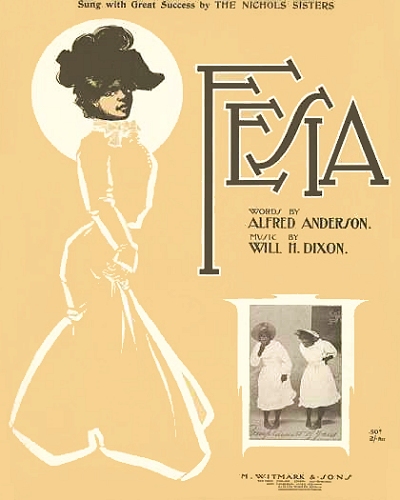

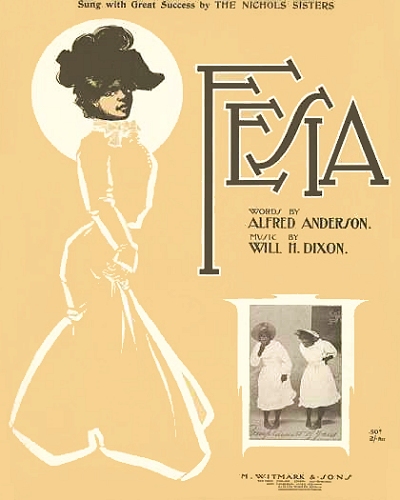

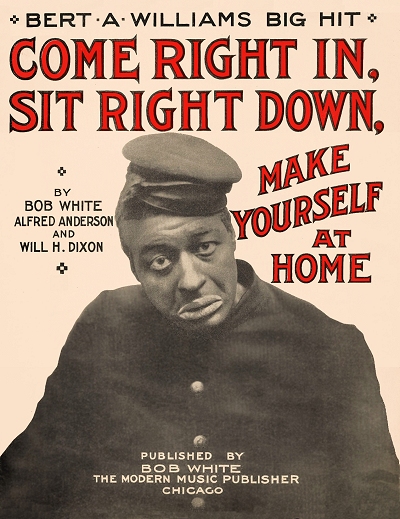

It was during the period from 1902 to 1904 that Dixon started composing songs and even musical plays to lyrics and libretti by black writer Thomas Alfred Anderson, who was more than a decade his senior. As the minstrel company's tours occasionally brought the writers to New York City, they made attempts at selling their works to publishers. Witmark took in a couple of their early works for publication in 1904, but not all of them saw the shelves, languishing in storage. Dixon and Anderson also hoped to have some of their works staged, but even in the somewhat liberal environment of Manhattan this was a longshot at that juncture. While composer/performer Will Marion Cook and poet Paul Laurence Dunbar had enjoyed some significant success over the past several seasons, and the stage stars Bert Williams and George Walker were also starting to shine, meetings with the latter two or even other publishers bore no fruit concerning any productions. Anderson decided to return to Chicago, but Dixon remained in New York, determined to be heard.

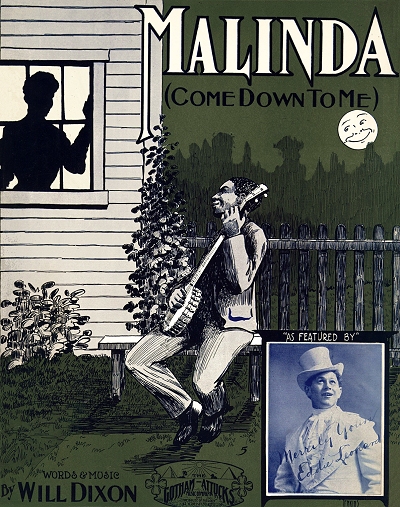

Learning very quickly that there were bad players in the publishing business, many of them White men taking unfair financial advantage of black talent, Will soon fell in with a much more congenial crowd. This included the likes of Cook, his associates Shep Edmonds and Richard C. McPherson (a.k.a. Cecil Mack), and composer/performer Ernest Hogan. (Refer to their individual biographical entries here for more context.) The first three had come together to form the Gotham-Attucks publishing firm, which for a few years provided good opportunities for black performers and composers. They released a couple of Will's works starting as early as 1905. More importantly, however, was Hogan, who quickly recognized Will's potential as a conductor and arranger, not just a singer.

Cook, Hogan and Dixon were the primary force behind the formation of the Memphis Students Company in 1905 (possibly named after a similar troupe that had known some success in the early 1890s). They were comprised of around 25 members including a chorus, orchestra, and several variety players. Ernest became their lead comedian and singer, and Dixon the music director. Other notable talents included singers Anna Pankey Cook and Abbie Mitchell (W.M. Cook's wife), and dancer Ida Forsyne as "Miss Topsy, the girl who was not born, but who just grew." Will Cook wrote the bulk of the songs with Dixon providing some numbers now and then with Anderson. They worked many of the vaudeville theaters of New York City, including over 100 performances at the well-known Oscar Hammerstein I Victoria Theater and the Paradise Roof Garden on the roof of that theater, as well as Sunday nights at the Orpheum and other appearances at Tony Proctor's famous 23rd Street venue.

Cook, Hogan and Dixon were the primary force behind the formation of the Memphis Students Company in 1905 (possibly named after a similar troupe that had known some success in the early 1890s). They were comprised of around 25 members including a chorus, orchestra, and several variety players. Ernest became their lead comedian and singer, and Dixon the music director. Other notable talents included singers Anna Pankey Cook and Abbie Mitchell (W.M. Cook's wife), and dancer Ida Forsyne as "Miss Topsy, the girl who was not born, but who just grew." Will Cook wrote the bulk of the songs with Dixon providing some numbers now and then with Anderson. They worked many of the vaudeville theaters of New York City, including over 100 performances at the well-known Oscar Hammerstein I Victoria Theater and the Paradise Roof Garden on the roof of that theater, as well as Sunday nights at the Orpheum and other appearances at Tony Proctor's famous 23rd Street venue.This success prompted Cook to organize a European tour for the company. However, Hogan wanted to stay in New York City and heavily objected to the idea. Cook, not known for his even-temperament, decided to go ahead with the tour, prompting Hogan to sue him to prevent their travel. Cook ignored the resulting injunction, simply renaming the group to the Tennessee Students, and then Memphis Students. Even before they tried to embark on their tour, Hogan made the tiff very public, causing him to put the following warning out in the Sunday Telegraph and other New York papers in early October:

WARNING TO MANAGERS

Information Has Come to Me That Some Malicious Negro Is OfferingTHE MEMPHIS STUDENTS

FOR ENGAGEMENTS$100 REWARD will be paid for information leading to the arrest of this contemptible person. This is my original idea and conception and NO ONE has the right to offer this act but my sole agents, Wm. Lykens and Wm. Morris.

The Memphis Students is the act which enjoyed the phenomenal run of the entire Summer past at Hammerstein's Victoria. Each member is under contract

to me for one year or more and are not offering their services to anyone else…

NOTICE: Owing to a close Starring engagement under the management of Messrs. Hurtig & Seamon, I will soon be compelled to leave the Students, but the organization will immediately begin rehearsing (under my personal supervision) new and original music written expressly for them by

WM. DIXON, The Greatest Negro Choral Director…

(Signed) ERNEST HOGAN

Ultimately, not all 25 members signed up with Cook, but enough headliners stayed involved to encourage Cook and Dixon to proceed. By November 1905 they were headed out to conquer the European continent, specifically the Follies Berge in Paris, France, where they remained through early March 1906. Over the next few months, it appears that Hogan and Cook resolved their differences enough to get along again. On the group's return they did a run at the music hall managed by Hogan's producers, Jules Hurtig and Harry Seamon. Dancer Ida Forsyne, one of the headliners, had stayed behind in Europe, working engagements for the next several years as an actress in France and England. A passport issued to Dixon showed that he had already considered staying behind himself, noting a possible residency of "a year or two," perhaps to engage in further musical study. However, he came back in either March or April 1906.

Over the next few months, it appears that Hogan and Cook resolved their differences enough to get along again. On the group's return they did a run at the music hall managed by Hogan's producers, Jules Hurtig and Harry Seamon. Dancer Ida Forsyne, one of the headliners, had stayed behind in Europe, working engagements for the next several years as an actress in France and England. A passport issued to Dixon showed that he had already considered staying behind himself, noting a possible residency of "a year or two," perhaps to engage in further musical study. However, he came back in either March or April 1906.

Over the next few months, it appears that Hogan and Cook resolved their differences enough to get along again. On the group's return they did a run at the music hall managed by Hogan's producers, Jules Hurtig and Harry Seamon. Dancer Ida Forsyne, one of the headliners, had stayed behind in Europe, working engagements for the next several years as an actress in France and England. A passport issued to Dixon showed that he had already considered staying behind himself, noting a possible residency of "a year or two," perhaps to engage in further musical study. However, he came back in either March or April 1906.

Over the next few months, it appears that Hogan and Cook resolved their differences enough to get along again. On the group's return they did a run at the music hall managed by Hogan's producers, Jules Hurtig and Harry Seamon. Dancer Ida Forsyne, one of the headliners, had stayed behind in Europe, working engagements for the next several years as an actress in France and England. A passport issued to Dixon showed that he had already considered staying behind himself, noting a possible residency of "a year or two," perhaps to engage in further musical study. However, he came back in either March or April 1906.By this time Hogan had gone on to his own New York show. So, his wife, Abbie, headlined for the troupe when they retook the New York stages. Then, virtually nothing was heard from the Students from late 1906 into early 1908, when they reappeared on the New York vaudeville theater scene, getting positive notices for much of the year, and on a few occasions in 1909. They also toured briefly doing engagements mostly in the Northeast states, but it is possible that Dixon was not involved in those travels. The group was largely disbanded before 1910 in order to focus on new horizons, such as the growing Clef Club run by James Reese Europe and Ford Dabney. In later years, writer James Weldon Johnson recalled the Memphis Students, as well as one of the characteristics of their now-esteemed music director, who has sometimes been referred to as The Dancing Conductor:

The first modern jazz band ever heard on a New York stage, and probably on any other stage… made its debut at Proctor’s Twenty-Third Street Theatre in the early spring of 1905. It was a playing-singing-dancing orchestra, making dominant use of banjos, mandolins, guitars, saxophones, and drums in combination, and was called the Memphis Students…

Will H. Dixon's choreography was full of novelty: All through the number he would keep his men together by dancing out the rhythm generally in graceful, sometimes in grotesque, steps. Often an easy shuffle would take him across the whole front of the band. This style of directing not only got the fullest possible response from the men, but kept them in the right humour for the sort of music they were playing.

Just the same, when the Students returned in 1906, Will, perhaps reluctant to deal with any fallout from his defection from Hogan, returned to Chicago for a short time. He gravitated to one of the hottest tickets in town, the Pekin Theatre, which was quickly becoming the domain of Joe Jordan, who was writing and directing monthly—sometimes weekly—shows for the establishment. As Jordan was frequently in New York City, they may have also crossed paths there. While in town, Will was reportedly Jordan's assistant and co-wrote at least two musical productions. By 1907, Will was back in Manhattan, and attempted to follow in the footsteps of his mentors at Gotham-Attucks starting his own publishing firm, the Will H. Dixon Music Publishing, Company. He set up shop in the Theatrical Exchange Building, 1431-33 Broadway, just a block south of the recently established Times Square. As with many small-time enterprises in a city bursting with them at the time, it did not last very long, but it helped to show his resolve to make a mark on New York and the world around him.

By 1907, Will was back in Manhattan, and attempted to follow in the footsteps of his mentors at Gotham-Attucks starting his own publishing firm, the Will H. Dixon Music Publishing, Company. He set up shop in the Theatrical Exchange Building, 1431-33 Broadway, just a block south of the recently established Times Square. As with many small-time enterprises in a city bursting with them at the time, it did not last very long, but it helped to show his resolve to make a mark on New York and the world around him.

By 1907, Will was back in Manhattan, and attempted to follow in the footsteps of his mentors at Gotham-Attucks starting his own publishing firm, the Will H. Dixon Music Publishing, Company. He set up shop in the Theatrical Exchange Building, 1431-33 Broadway, just a block south of the recently established Times Square. As with many small-time enterprises in a city bursting with them at the time, it did not last very long, but it helped to show his resolve to make a mark on New York and the world around him.

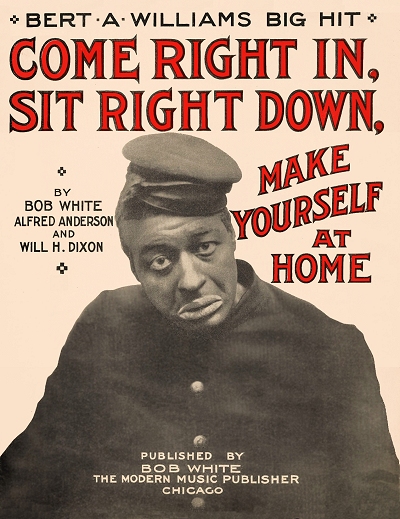

By 1907, Will was back in Manhattan, and attempted to follow in the footsteps of his mentors at Gotham-Attucks starting his own publishing firm, the Will H. Dixon Music Publishing, Company. He set up shop in the Theatrical Exchange Building, 1431-33 Broadway, just a block south of the recently established Times Square. As with many small-time enterprises in a city bursting with them at the time, it did not last very long, but it helped to show his resolve to make a mark on New York and the world around him.Will was quickly indoctrinated and assimilated into the upper echelon of the Black music fraternity of Manhattan, which included luminaries like Williams and Walker, Europe and Dabney, Henry S. Creamer, Theo Bendix, and, when he was in town, Joe Jordan. In addition to attending regular gatherings of the collective group at the Marshall Hotel in Manhattan, over the next few years he would collaborate with many of them as well for published sheet music, specialties for the stage to accompany dancers or actors, orchestral arrangements, and musical numbers performed for the Elite 400 of New York society. While not always a headliner, he was often out front leading a band or an orchestra.

A great honor was bestowed on him in 1909 when Will became a participating member of The Frogs, founded by Williams and Walker in 1908, in part as a promotion for their struggling Gotham-Attucks publishing firm. It was made up of the leading black composers and performers of New York during that time. Cecil Mack was the first secretary of the organization, headed by Walker and John Rosamond Johnson. While not directly beneficial to Gotham-Attucks, just the mention of the composers' or musician's names in the reports of various functions they held or appeared at was a peripheral form of publicity. They soon expanded the esteemed group to include professionals from other high-profile fields as well. Still, it was not quite enough to be of much help to the struggling publishing firm.

Dixon's efforts soon paid off financially as well as socially. While hardly affluent, for a Black artist in the big city he was able to afford some of the nicer things in life, like a lovely South Harlem brownstone dwelling with a decent piano. He was also well-liked and well-regarded by his peers and the general public. As was stated in some of his obituaries, "Will H. Dixon was gentlemanly in conduct and he possessed many qualities that stamped him as a man with a good heart and kindly intentions toward all." But he was also a man of opportunity, who did not waste his time in Europe during his visit, but studied what they had to offer in terms of music and culture, eventually integrating it into some of his works. Ultimately much of his income came from performance, not from his published works, a distinction usually reserved for the more prolific writers.

As was stated in some of his obituaries, "Will H. Dixon was gentlemanly in conduct and he possessed many qualities that stamped him as a man with a good heart and kindly intentions toward all." But he was also a man of opportunity, who did not waste his time in Europe during his visit, but studied what they had to offer in terms of music and culture, eventually integrating it into some of his works. Ultimately much of his income came from performance, not from his published works, a distinction usually reserved for the more prolific writers.

As was stated in some of his obituaries, "Will H. Dixon was gentlemanly in conduct and he possessed many qualities that stamped him as a man with a good heart and kindly intentions toward all." But he was also a man of opportunity, who did not waste his time in Europe during his visit, but studied what they had to offer in terms of music and culture, eventually integrating it into some of his works. Ultimately much of his income came from performance, not from his published works, a distinction usually reserved for the more prolific writers.

As was stated in some of his obituaries, "Will H. Dixon was gentlemanly in conduct and he possessed many qualities that stamped him as a man with a good heart and kindly intentions toward all." But he was also a man of opportunity, who did not waste his time in Europe during his visit, but studied what they had to offer in terms of music and culture, eventually integrating it into some of his works. Ultimately much of his income came from performance, not from his published works, a distinction usually reserved for the more prolific writers.In April 1909, Will was brought on by Aida Overton Walker, wife of George Walker who was ailing at that time, for an All-Star Benefit, likely for St. Phillip's Parish Home, one of her many social causes in the black community. As a matter of course and presentation to elevate the event, the group presented an operetta for the second half of the show, King's Guest. At the very same time, Ernest Hogan was less than a month from death, and George Walker would be gone within two years after a long illness. The loss of these pioneers and a change in direction to popular music played by top-notch black orchestras created a shift in direction for Dixon and many of his peers. By 1910, he would help co-found The Clef Club with James R. Europe, and become one of its primary leaders over the next two years, as well as arranger and composer. He shared this distinction with Europe and Ford Dabney, although their published output easily exceeded Will's. Dixon was also a member of several committees of the organization, and the stage director of a couple of their larger shows. At the time of the 1910 census, Will was either on travel somewhere or was somehow missed by the enumerator, as efforts to locate him in that record were fruitless.

As far as Will's reputation as a performer, his star was elevated during the early 1910s. He was not only busy working, but was routinely regarded as one of the black authorities on music, often consulted and quoted. In the New York Age of April 8, 1909, for which performer/writer Lester A. Walton had a regular column, Dixon and his peers were pressed on the issue, brought up frequently by "serious" musicians, on the status of ragtime's viability and health. Asking for comment, Walton printed the replies of five of New York's finest black musicians, including Dixon:

Only a few days ago in discussing what is commonly known as "ragtime" music, John Philip Sousa gave out the following statement: "Ragtime had the dyspepsia or gout long before it died. It was overfed by poor nurses. Good ragtime came and half a million imitators sprang up. Then, as a result the people were sickened with the stuff. I have not played a single piece of ragtime this season because the people do not want it." Since the announcement by the noted bandmaster that ragtime is a thing of the past [it still had at least eight healthy years left], musicians and critics have become involved in a controversy as [to] the correctness of Sousa's stand. As syncopated music is credited with being of purely Negro origin [the truth is actually a bit more complex], the dramatic editor of The Age recently wrote to some of the young and successful colored composers, asking them what they thought of Sousa's utterances on the subject…

(By Will H. Dixon.) Commenting on Mr. Sousa's criticism, I desire to say that I disagree with him. For instance, take the melodies of Will Marion Cook, they are more or less full of syncopation or what is commonly termed ragtime; likewise J. Rosamond Johnson's. Harry T. Burleigh, one of the greatest Negro composers America has produced, has just finished a piano cycle, the theme of which is taken from Darky folk-songs with syncopated rhythm. I feel confident in saying that Mr. Sousa, after reading the score of Mr. Burleigh's cycle, would know that it was the product of a master mind. The trouble is there are may worthless compositions thrown upon the market to-day, and for want of a better name they are termed 'ragtime selections.' I agree with Mr. Sousa that such are short-lived, but the melodious compositions in syncopated rhythm by such composers as I have mentioned shall never cease to be pleasing to the ear of a music-loving public.

On May 2, 1912, the Clef Club became the first organization of their kind to stage a concert in the now-famous Carnegie Hall. In addition to a 150-voice chorus, one of the highlights of the evening was a ten-member piano section of the large 125-piece orchestra, of which Will was one of those pianists. He had taken another step earlier in the year, marrying recently divorced light-skinned Missouri native Maude Mae Rubey Seay (known also as "Madam Seay") on February 1st, 1912. Both of them fudged their age more than just a little on the official New York City marriage record, with Will claiming to be 21 to his actual 33, and Maude 18 to her real age of 31. A graduate of Western College, she had been a teacher in the Macon, Missouri school district, and in 1902 was married to businessman Frank Seay, divorcing him in 1910. Maude had relatives in Chicago, and had also been engaged in the millinery business there, with a fine reputation for her hats. For Will, she seemed a good fit.

He had taken another step earlier in the year, marrying recently divorced light-skinned Missouri native Maude Mae Rubey Seay (known also as "Madam Seay") on February 1st, 1912. Both of them fudged their age more than just a little on the official New York City marriage record, with Will claiming to be 21 to his actual 33, and Maude 18 to her real age of 31. A graduate of Western College, she had been a teacher in the Macon, Missouri school district, and in 1902 was married to businessman Frank Seay, divorcing him in 1910. Maude had relatives in Chicago, and had also been engaged in the millinery business there, with a fine reputation for her hats. For Will, she seemed a good fit.

He had taken another step earlier in the year, marrying recently divorced light-skinned Missouri native Maude Mae Rubey Seay (known also as "Madam Seay") on February 1st, 1912. Both of them fudged their age more than just a little on the official New York City marriage record, with Will claiming to be 21 to his actual 33, and Maude 18 to her real age of 31. A graduate of Western College, she had been a teacher in the Macon, Missouri school district, and in 1902 was married to businessman Frank Seay, divorcing him in 1910. Maude had relatives in Chicago, and had also been engaged in the millinery business there, with a fine reputation for her hats. For Will, she seemed a good fit.

He had taken another step earlier in the year, marrying recently divorced light-skinned Missouri native Maude Mae Rubey Seay (known also as "Madam Seay") on February 1st, 1912. Both of them fudged their age more than just a little on the official New York City marriage record, with Will claiming to be 21 to his actual 33, and Maude 18 to her real age of 31. A graduate of Western College, she had been a teacher in the Macon, Missouri school district, and in 1902 was married to businessman Frank Seay, divorcing him in 1910. Maude had relatives in Chicago, and had also been engaged in the millinery business there, with a fine reputation for her hats. For Will, she seemed a good fit.As was common during this socially turbulent time, musical tastes and inclination were changing again, and both Europe and Dabney had some specific obligations to White patrons that diverted their attention away from the Clef Club. Will was still a leader in the organization until at least 1916. But the scope of available work was changing. In addition to the Clef Club, Will had joined the Smart Set Company in 1910, which was run by Salem Tutt Whitney, and originated by Tom McIntosh and Sherman H. Dudley. Started years earlier, by 1912 they had split into northern and southern components, with Whitney in charge of the Southern Smart Set Company. A bit closer to the minstrelsy style that Will had gotten his start in, they toured theaters and Chautauquas throughout the Mid-Atlantic into the South. It is unclear how often Will went on the tours, as he was also trying to maintain his profile in New York City with the Clef Club and other concerns.

as he was also trying to maintain his profile in New York City with the Clef Club and other concerns.

as he was also trying to maintain his profile in New York City with the Clef Club and other concerns.

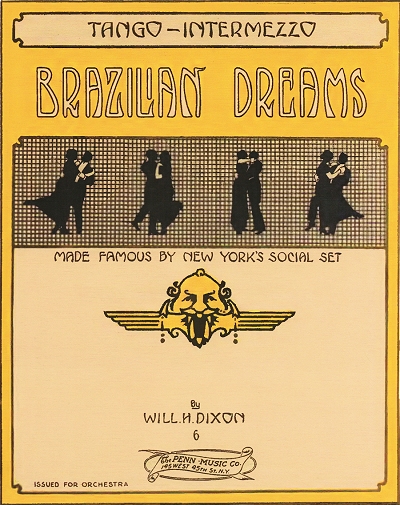

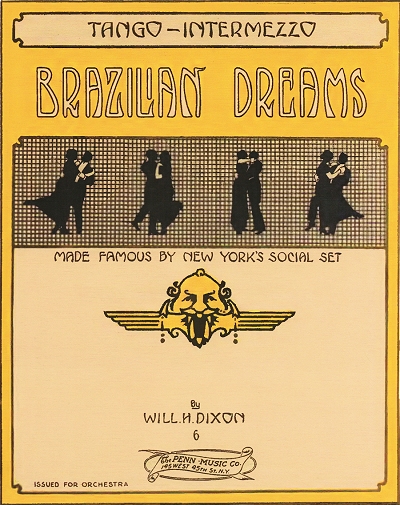

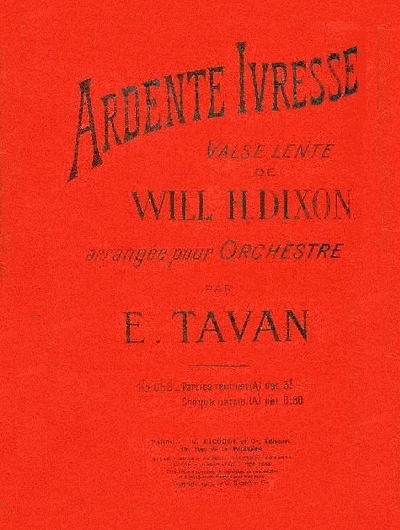

as he was also trying to maintain his profile in New York City with the Clef Club and other concerns.The period of 1913 to 1914 was a particularly productive one for Will in terms of quality of composition. Four works from 1913 are standouts showing Dixon's appreciation of non-popular music forms integrated into a popular but artistic format. Among them were the habanero-tango Brazilian Dreams, the gentle Fox-trot September Eve, and the beautiful waltzes, the sublime and dramatic Breath of Autumn, and Ardente Ivresse. The following year saw the release of the maxixe La Nativa, and another tango, Delicioso. Brazilian Dreams soon became part of the stable of tunes used by the famous dancing pair of Vernon and Irene Castle, who had also engaged Europe and Dabney to provide them with engaging dance numbers. The tune also found its way into the Ziegfeld Follies for the 1916 traveling edition. During this period the Dixons also spent considerable time back in Chicago, where Maude tended after her hat business and other family matters.

Well into 1915, Will's name still appeared in the entertainment and music pages of New York and Chicago newspapers, either as a participant, or as a contributor of a performed composition. He was spending more time in the Windy City than the Big Apple, bouncing between them as the need transpired. That year he helped to make another important contribution to the world as on June 1, 1915, Maude gave birth to their daughter, Francesca "Frankye" Alfreta Dixon in Chicago. She would be raised in both Chicago and Harlem, and had a considerable musical future of her own. Unfortunately for Will, by this time the ravages of the sporting life common to so many composers and musicians of this time were starting to catch up to him. He shared something in common with fellow New York composer Scott Joplin, as the onset of tertiary syphilis was starting to tighten its grasp on Dixon.

He shared something in common with fellow New York composer Scott Joplin, as the onset of tertiary syphilis was starting to tighten its grasp on Dixon.

He shared something in common with fellow New York composer Scott Joplin, as the onset of tertiary syphilis was starting to tighten its grasp on Dixon.

He shared something in common with fellow New York composer Scott Joplin, as the onset of tertiary syphilis was starting to tighten its grasp on Dixon.Something else that Will had in common with Joplin was the desire to bring an opera, for which he had written both the score and libretto, to the New York stage, as was stated in his obituary in the New York Age on June 7, 1917. Will continued to work in the 1916 edition of the Southern Smart Set show titled George Washington Bullion Abroad, but was evidently unable to complete the tour because of ongoing issues with his physical and mental state, due to the effects of the syphilis. Some reports suggest that Will perhaps was working beyond his mental capacity at that point, and he eventually had to return to his early home of Chicago where his mother still resided. He was also admitted to ASCAP not too long after the organization was formed. However, Dixon spent most of his final months in his mother's care into the spring of 1917. Just six weeks after Scott Joplin's death, Will succumbed to the same fate in Chicago at age 37 while in the care of his mother. He was buried at Oak Wood Cemetery in Chicago. Will was remembered by many in obituaries over the next three or so weeks with kind notices about him prevailing. However, prior to his death the Chicago Defender had published an article in January 1914 on Dixon as a composer, which summed up his tragically short life in the best of terms:

Gentlemanly, courteous, and affable, ever ready to give a helping hand to the fellow farther down, is it to be wondered at that his friends are numbered by the hundreds, and those who have not had the rare good fortune to know him personally have enjoyed the fruits of his efforts in a musical way. For Mr. Dixon is a composer whose fame has spread over both [American and European] continents. The world's greatest singers have taken pleasure in interpreting his exquisite musical compositions, and in the instrumental field he held an enviable position… Mr. Dixon’s talent is best displayed in his classical numbers and critics say his work forcibly reminds them of the old masters. Mr. Dixon is not only a credit to Chicago, but a credit to his race.

But Will Dixon's legacy does not end there. Musical talent, good looks, goodwill, and a desire to matter were possibly genetic in this case, along with a widow who did her best with what she had to make a good life for their daughter.

Maude was remarried in 1919 to World War I veteran and chiropractor, Captain Alonzo Myers, who had served with the all-Black Buffalo Soldiers unit. It was clear to both mother and stepfather that little Frankye had inherited many of her father's fine attributes, and was a bit of a child prodigy when it came to music. Maude and Alonzo did very well for themselves, entering into the real-estate business in the early part of the "Roaring Twenties." They would eventually own a professional building on 130th Street in Harlem, and Maude became even more successful there than she had in the hat business. The Meyers were partly responsible for opening up an apartment coop at Morningside Park, providing an affordable and nice place for people of color to live.

|

Frankye was classically trained at the piano in her youth, and eventually attended the Juilliard Music School as well as New York University, capped off by the Teacher's College at Columbia University. She put her training to good use, giving piano and organ recitals and concerts from the 1930s forward, acting as an accompanist to many famous black performers, and even writing on music for periodicals and newspapers. From 1941 to 1942 Frankye toured the United States as an accompanist for the distinguished contralto R. Louise Burge, who was associated with Howard University in the District of Columbia. She also helped break color barriers by performing with the NBC Symphony Orchestra as conducted by no less than Léopold Stokowski. When not on tour, she had a Harlem music studio that trained a new generation of black musicians, preparing them for the joys and hardships of music in a world that was not always accepting of their cultural background, inspiring them to aspire beyond those limits. Now as Mrs. Thompson, Frankye eventually became a professor of music at Howard University, where she spent much of her later career making a difference in the lives of Black students. Between Frankye and Maude, the essence and memory of Will H. Dixon has been kept alive, and he is still highly regarded today by historians and music lovers.

Note: There are a few pieces ranging from 1899 to 1917 that have lyrics written by either a Will H. Dixon or William H. Dixon. Given the identity and location of the composers, who were all White, and other factors within the timeline, as well as the fact that this particular Dixon was pretty much a music-only writer with little lyrical experience, these pieces are called into doubt as two other white William H. Dixons were found living in Illinois and Indiana, and were more likely to have been the lyric contributors. Therefore, those pieces are not referenced in this essay.

Some of the best detailed research on Will Dixon was done by Rick Benjamin, Director of the Paragon Ragtime Orchestra, in preparation for his Black Manhattan album series. I highly recommend obtaining this set for both the music and liner notes. Information on Frankye was partially derived from an article on Ancestry's WeRemember.com, as maintained and researched by Lawrence H. Levens, Guardian of the Dixon Family Papers. Additional information on possible early compositions with Shaw are courtesy of Samuel Carner. Much of the information gathered here on both Will and Frankye came from newspapers and other contemporary sources, as well as the usual records of government origin, such as enumerations. Some of the information on Dixon's early years and the Lincoln School came from historical societies in Ohio County, West Virginia.

Compositions

Compositions