RagPiano.com - Guide to Silent Movie Music

An Essay on Silent Films through the 1920s and

the Music that Underscored It

by Bill Edwards

Contents Copyright ©2004/2015 by William G. Edwards

A BRIEF HISTORY OF SILENT FILM

From the time that the first commercial movie theaters showing projected pictures started to open (1902 in the United States), entrepreneurs and technicians alike tried a variety of methods to replace the clicking of the projector with something more engaging. Sometimes either the theater owner or somebody hired by him might stand behind the screen providing dialogue and sound effects, something a bit disarming or awkward at times. Thomas Edison and his counterparts experimented with synchronized discs but they did not always synchronize properly, as highlighted to great comic effect in the 1952 film Singing in the Rain. The most obvious and low cost answer to creating a film sound track that would convey some of what was happening on the screen was to provide music.

So it was that nearly simultaneously, theater owners sought out pianists of either gender to provide entertainment between reels and accompany the action during. Many were able to make a career of this, not the least of which was Canada's fabulous ragtime composer/performer

Willie Eckstein. But even Aunt Myrtle could make a pretty decent income playing for the ten-cent shows on the corner. Many premieres and some of the higher-end theaters used orchestras of varying size with pre-composed scores written specifically for a certain film.

A scene of a film within a film, showing the pianist hardly at work at an upright. Many used elaborate organs or player pianos. |

In other instances, in an effort to provide versatility and variety, special mechanical pianos and organs were installed in theaters that not only created a great venue for concerts, but also threw in a variety of sound effects and timbres not available on the standard upright piano. Many instruments, in addition to their many stops ranging from xylophone to diapason horns, also featured moos, quacks, barks and other sound effects at the performer's disposal.

Still, this was hard work. The 1985 Dire Straits song Money For Nothing says about the perception of musicians, "That ain't workin', that's the way you do it, Money for nothin' and your chicks for free!" However, consider that not only was the performer captive for six or seven showings a day, up to ten hours, but they were further tasked to provide the proper mood music for a wide variety of genres, cultures, emotions and specific incidents. And if the movie was bad - well, they had to endure that bad movie and try to keep it fresh or improve on it with their music. Some were even asked to play appropriate music under newsreels, a singular challenge that might be hard to imagine now. If you think about memorable movies of the past 40 years, you will often note how well you remember parts of the score. So in some ways, a good pianist/organist or orchestra could subtly affect the opinion of a movie reviewer or audience member. To ease some of this pressure, and often to cut costs, automated orchestrions known widely as Fotoplayers (a trademarked name applied to most of them no matter the manufacturer) with multiple roll capability were manufactured specifically for the cinema. This would give the better pianists some time off (albeit permanently on many occasions) and allow the lesser pianists an opportunity to play on occasion between manipulating the rolls or where there was nothing else appropriate available.

To facilitate the proper moods, some studios commissioned scores for their movies, or perhaps just specific songs, and sent these out with the prints. It is little known that one of the more prolific composers of music for both comedy and pathos was Charlie Chaplin himself, who frequently composed music (notated by a professional arranger) for chase scenes, sad love scenes, and the like for distribution with his films. In many cases, you were able to purchase sheet music in the lobby of a piece you heard inside that could be viewed as either a memento or an advertisement. But the customized film score was an exception. The rule remained that the keyboardist was often on his own. In an effort to address this market, a few enterprising publishers created folios of mood music that was suited specifically for cinema. They provided music for varying cultures, using stereotypical musical motifs, as well as a variety of love scene schmaltz, military and Civil War tunes, mysterious melodies, and the inevitable chase or hurry scene music. With a little bit of practice a pianist could prepare for the next week of music in just a couple of hours based on the contents of one of these collections.

To illustrate this from the point of view of an active cinema pianist from the era, we need only to turn to Marcella A. Wirges, a Chicago composer and pianist who also taught with and wrote for the firm of entrepreneur Axel W. Christensen. He had founded a school of ragtime before 1910 that taught the skill of syncopation and mild improvisation to thousands of willing amateur pianists, and his popular magazine was filled with musical numbers and musical tips, like this article, HINTS FOR PICTURE PIANISTS, in the August 1916 issue of Christensen's Ragtime Review:

Don't be what the people call a thumper. Nothing jars more on the ears of the audience, than a lot of noise. Some pianists have the idea that to gain a reputation as (SOME PIANIST), they must make all the noise possible and "tear the piano apart," (so to speak). FAR BE IT FROM SUCH! To be an A1 picture player, a pianist must bring out all there is in a picture, and all the finer effects are lost if the pianist keeps FF from the time [the] "welcome" slide is thrown on the screen, until "Good night" is shown.

For comedy pictures, lively music, but not too loud, unless action is very rough, as the people go to a theater to see the pictures, and if the music is too loud, it draws their attention from the picture. The music should fit into the picture. Popular songs, rags, or any 2/4 tempo, is very good, unless eccentric – then, some popular fox-trot, rag or chicken reel fits in nicely.

Western pictures require 6/8 and 2/4 marches, also cowboy songs, and always follow the action of the picture. If the action is slow, play slow; if scene is chasing robbers, etc., where horses and riders are speeding the limit, play fast.

Series and educational pictures – concert waltzes and overtures from the Standard operas. In the animated weeklies, always change with each scene. If soldiers are marching, play "America First," or any popular or national patriotic air. For showing latest fashions, with ladies in beautiful costumes, play "Beautiful Lady" or some pretty waltz.

Selections from musical comedies are good, for comedy-dramas, which do not require any particular style of music. Always try to play appropriate music, whenever possible. For example:

(No. 1) Young man sees pretty girl, tries to flirt – "What would be more appropriate than to play" _ "Pretty Baby," "Whose Pretty Baby are you Now?" or Will Carroll's great ballad "If I Could Call You Mine."

(No. 2) Where there is a pathetic scene of a mother and child, "Mother" [a.k.a. M-O-T-H-E-R] fits very well.

Pictures depicting scenes and characters of Ireland, always play as much Irish music as you can.

Pictures relating to Germany, require German airs, etc. [Note that during WWI these were not too popular in the U.S.]

[Civil] War pictures of the Blue and the Gray – never play a Southern patriotic air, when the Northern flag is shown, or play a Northern air when the Southern flag is seen. Music for the war pictures usually [requires] a lot of noise especially for battle scenes, and here is where our friend "the thumper" can SHINE.

To follow a picture scene for scene, a pianist must have quite a number of pieces by memory. I always make it a rule not to read a sheet of music for the first show. If there is an intermission, a pianist has time to sort the program for the following shows. Some managers get the synopsis of the plot a few days ahead of the date to be shown. In this case, the pianist has ample time to get the program ready. All pianists aren't gifted in the art of improvising, which helps [considerably] in following a picture.

If you are in the habit of taking a few minutes rest while the show is on, if the film should break and leave the curtain dark, always play something, never have any dead waits in a theater, but have the music go with a snap. If you want to take a few minutes rest, time the picture, and don't stop playing when the picture stops, but keep on playing till [the] operator has [the] next reel well started.

When there is an orchestra, it is almost impossible to follow a picture, unless, you can sort the program before hand and know when to change the music. Those new photo-players [often spelled foto-player] now used in a number of theaters, are a relief to some of the pianists who have been working with leaders, who didn't have the first idea what to play for a picture, but would be playing a heavy overture when lively scenes were on, and I also wish to state that no dying man wants to hear "Too Much Mustard."

Here is success to the various photo-players, when they have a musician who understands the instrument and can follow the picture.

In 1922 the prime developer of the vacuum tube that made electronic voice reproduction and radio possible,

Lee DeForrest, presented a method of recording synchronized sound on film. While experiments were done over the next few years, it was not until 1926 that Warner Brothers took a chance with a similar system that used 33 1/3 records designed to play synchronously with a reel of film, and with that they created a single-reel short with

Al Jolson called

A Plantation Act. The Warner executives were quite impressed, enough that they signed Jolson to debut the following year in

The Jazz Singer (over equally fine candidates

Eddie Cantor and

Georgie Jessel), the first "All singing, all talking," all sound with no musician required motion picture. The success of the film when it opened in October of 1927 set all of the studios into a metamorphasis requiring new sound stages, new talents, etc. It also spelled the death knell for the theater musician. The runaway success of

Walt Disney's Steamboat Willie the following year was perhaps what pushed the public demand for sound films overwhelmingly over silents.

Some studios continued to make silent films regularly over the next three years, using up their remaining film stock, but by 1930 most of the theaters in country had either converted to sound or went out of business. Some went on to play or compose in either film or other venues, but the timing coinciding with the world-wide economic downslide was simply cruel to the majority of these people who feel they had outlived their usefulness. What happened to the majority of the Fotoplayer-style instruments is a mystery, as there may have been as many as 8,000 of them at one point in daily service.

Over the next decade some theater owners may have wished they had kept these instruments and waited for some standardization, as there were optical and disc formats, as well as forays into anamorphic widescreen and multi-channel surround sound (most notably Fantasia) that required constant upgrading or equipment shifts. It should be noted that Chaplin defied the odds by making two more silent films after the alleged demise of the genre, City Lights (1931) and Modern Times (1936), although both had recorded soundtracks featuring some of Chaplin's work. The most successful silent film of the last 50 years was the Mel Brooks comedy Silent Movie, in which the intentional irony is that the only word spoken in the film comes from the lips of famed mime Marcel Marceau. Still, silence has its place, and some of the most memorable movie scenes to this day (think Ghost) have no dialogue in them whatsoever. With the resurgence of the original silents on DVD with appropriate soundtracks, perhaps somebody of the current generation of filmmakers will once again be inspired to give the genre a try once more.

At one point in the early 1920s there were close to 18,000 movie houses in the United States alone. Given the variations in capacity we can generally break down the methods to accompany the films into four general groups. Starting with the largest theaters, usually the vast palaces that held 2,000 or more patrons and were used largely for premieres or road shows, one might often hear an orchestra playing either a score specifically written for a film (D.W. Griffith had commissioned them for his epics) or an otherwise appropriate accompaniment. Being that common amplification was still in the future during the 1910s and early 1920s, orchestras were necessary not only to provide music but to simply be heard in cavernous spaces, or even over projector noise in some instances. However, this was practical only for evening shows and weekends, so a second method of providing accompaniment on a more modest scale needed to be installed in these theaters and similarly large ones that could not afford the space or expense an orchestra required.

The answer was the organ. Large pipe organs were, for the most part, a one-time expense save for tuning and maintenance. In addition, paid concerts could be given by the more adept artists, providing additional revenue for the theater owner. Organs that had from 2 to 7 manuals were installed, and they provided the organist with a wide variety of stops and sound effects. Xylophones and percussion instruments were controlled with small servers and solenoids directly from the keys or buttons at the keyboard, and marvelous sub-sonic tones could be had from a rank of 32' pipes. The ranks of sound could also be placed around the theater, providing musical a surround sound experience that is still hard to top to this day. Skilled organists were considered to be among the most employable musicians in many parts of the country. It was also the first instrument for many successful musicians who later turned their interest elsewhere, such as a young Thomas "Fats" Waller. But organs could be temperamental due to the array of physical and electrical connections, and the smaller pipe ranks were difficult to keep in tune with larger ranks and pianos. Still, it was usually the finest theater in town that could boast about their massive Seeburg or mighty Wurlitzer. There are precious few restored organs left, but most of them are maintained, performed on and revered by societies created for that purpose.

The smallest theaters usually employed a pianist, or a player piano at the very least, and often had no sound at all. The latter was a situation often lamented by avid filmgoers and sometimes the actors themselves, as the silence encourage people to hold all matter of discussion while the plot unfolded on the screen. So most theaters tried to have at least minimal sound. The advantage of a player piano was that the skill level required to provide the music was understandably reduced, along with the fees to employ someone to run it. Alternately, some better pianists were able to take a break of sorts and let the piano do the singing while they waited for the next scene, or perhaps took another puff or sip of whatever was their pleasure. However, the sound of a piano, even with most of the wood removed, would fill a theater of up to 150 effectively, getting lost in larger halls. For those in-between sized theaters of 150 to 1500, and there may have been as many as 10,000 or this size in the 1920s, something had to be done to accommodate musical needs.

FILM MUSIC

Two of the better know folios of "Moving Picture Music" are presented here, along with what will be a growing collection of movie-specific tunes. They will also eventually be available on a CD, allowing you to create your own film soundtracks for anything from home movies to Chaplin classics. Please note that some of the compositions do present cultural stereotypes in their melodic makeup, but that this is a historical treatise of these books only, which does not necessarily reflect this performer's point of view on these cultures. In addition are some pieces known to have been written for or used in silent "fotoplays." So grab your popcorn, turn the TV sound down, and enjoy these musical vignettes.

CONTENT AND TITLES ARE

STILL UNDER DEVELOPMENT

MOVIE MUSIC FOLIOS

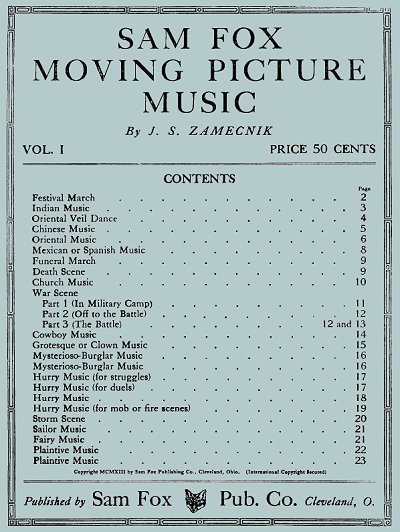

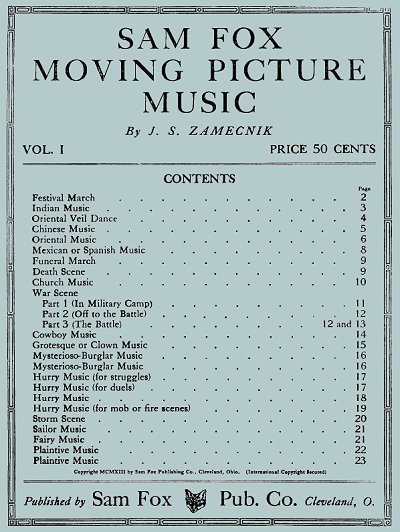

Sam Fox Moving Picture Music

Composed/Arranged by J.S. Zamecnik - 1913

|

1. Festival Music

2. Indian Music

3. Oriental Veil Dance

4. Chinese Music

5. Oriental Music

6. Mexican or Spanish Music

7. Funeral March

8. Death Scene

9. Church Music

10. War Scene

Part 1 (In Military Camp)

Part 2 (Off to the Battle)

Part 3 (The Battle) |

11. Cowboy Music

12. Grotesque or Clown Music

13. Mysterioso-Burglar Music

14. Hurry Music (for struggles)

15. Hurry Music (for duels)

16. Hurry Music

17. Hurry Music (for mob or

fire scenes)

18. Storm Scene

19. Sailor Music

20. Fairy Music

21. Plaintive Music

22. Plaintive Music |

In many cases, such as with the

Remick Folio below, theatre musicians used a combination of original pieces and snippets of other well-known works from popular songs to classical music. In an effort to be both specific to the task and to avoid copyright entanglements, Zamecnik composed the contents of this folio from scratch. Also, many of the common melodies used for Civil War or similar scenes were widely available and well-known, and where that didn't work the pianist could certainly fill in a waltz or a rag. In this folio, Zamecnik successfully addresses the issues of appropriate music to help bolster the action or emotional content of what was on the screen at any particular time. It also provided a nice style template for pianists who were less experienced and lacked the improvisational variety necessary to keep the music fresh. Zamecnik further designed it so that the pieces were not out of the technical reach of the average semi-professional musician.

Some of the more ethnic pieces may sound vaguely familiar, but this is largely a result of the use of stereotyped chord progressions or intervals based either in fact or perceptions of such music in regard to its intended country of origin. Also note some changes in perception that have occurred in the decades since this folio was released. Cowboy music was well-defined starting in the 1940s with bold and sweeping soundtrack scores, but at this time it was usually some kind of loping or trotting rhythm that defined the genre, and bears little resemblance even to the cowboy singing style that would emerge in the 1930s. There are many varieties of "hurry music" available in part because dialogue scenes of any length were difficult to pull off in a media where the voice was not available to emote, prompting directors to include more action and less talk. While this folio lacks much of the world-music themes prevalent in the Remick Folio, it is still well-crafted and often referred to for content or adaptations of modern music soundtracks applied to silent films restoration, something in which I have been fortunate enough to participate in.

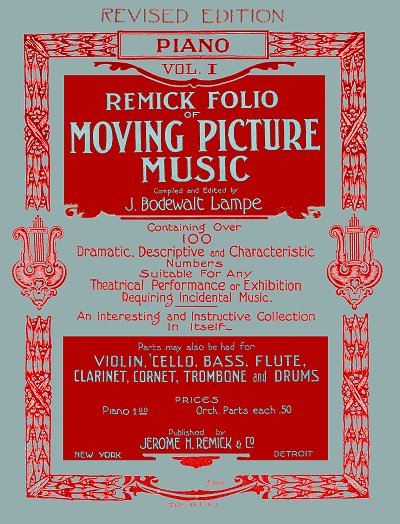

The Remick Folio of Moving Picture Music

Composed/Arranged by J. Bodewalt Lampe - 1914

|

1. Home, Sweet Home (Farm)

(Fireside) (U.S. War)

2. Battle Hymn of The Republic

(John Brown's Body) (U.S. War)

3. Marching to Georgia (U.S. War)

4. Yankee Doodle (Victory)

(U.S. War)

5. Old Folks at Home (Swanee

River) (Confederate) (Fireside)

(Plantation) (U.S. War)

6. Maryland, My Maryland

(Confederate) (U.S. War)

7. Dixie Land (Confederate) (Negro)

(U.S. War)

8. The Girl I Left Behind Me

(Drum Corps) (U.S. War)

9. The Vacant Chair (Fireside)

(U.S. War)

10. The Soldier's Farewell (Parting)

(U.S. War)

11. Tenting Tonight (U.S. War)

12. Trumpet Calls: Reveille,

Assembly, Mess, Charge,

Retreat, Taps (U.S. War)

13. Trumpet March (Bugle Corps)

(U.S. War)

14. Convict's March (Lockstep)

(Rogue's March) (U.S. War)

15. When Johnny Comes Marching

Home Again

(Return of Soldiers) (U.S. War)

16. America (My Country, 'Tis of

Thee) (Victory) (U.S. War)

17. The Star Spangled Banner

(Victory) (U.S. War)

18. Omaha Love Song

(American Indian)

19. Iroquois Tribal Melody

(American Indian)

20. Indian Shadow Dance

(American Indian)

21. Ojibway War Song

(American Indian)

22. Indian War Dance

(American Indian)

23. Cowboy

24. Cowboy Dance (Reel)

25. Reuben, Reuben (Country Man)

(Farm)

26. For He's a Jolly Good Fellow

(It's A Way We Have at Old

Harvard) (We Won't Go Home

Until Morning) (Club)

(College Boys) (Drinking)

27. Razzle Dazzle (College Boys)

(Drinking)

28. The Bamboula (African) (Zulu)

29. Tango (Argentine) (Caberet)

(Cuban) (South American)

30. Deutschland uber Alles (Austrian)

(German) (Vienna)

31. La Brabanconne (Belgian)

32. Bulgarian

33. Chinese

34. Chinese Serenade

35. Rule Britannia (English)

36. The British Grenadier (English)

(London)

37. The Marseillaise (French)

(Labor Demonstration)

38. Parisian Life (French) (Cabaret)

39. Sons of Greece (Greek)

40. Die Wacht am Rhine (German)

41. Halli Hallo (Medley Waltz)

(Lauterbach) (Club) (College

Boys) (Drinking) (German)

42. Mazel Tof (Hebrew)

43. Rakoczy March (Gipsy)

(Hungarian)

44. The Wearing of the Green (Irish)

45. Endearing Young Charms (Irish)

(Love Scene)

46. Garry Owen (Irish) (Jig)

47. Italian

48. Santa Lucia (Gondola) (Italian)

(Neapolitan)

49. Processional Tune (Japanese)

50. La Paloma (Central American)

(Cuban) (Mexican) (Panaman)

(South American) (Spanish)

|

51. At the Loud Cry of War

(Central American) (Mexican)

52. La Golondrina (Mexican)

(Serenade)

53. (Algerian) (Egyptian)

(Moorish)

54. (Arabian) (Hindoo) (Oriental)

(Persian)

55. (Arabian) (Hindoo) (Oriental)

(Persian)

56. (Arabian) (Hindoo) (Oriental)

(Persian)

57. Wallachian Dance (Roumanian)

58. Little Minka (Russian)

59. (Finnish) (Norwegian)

(Scandinavian) (Swedish)

60. The Campbells Are Coming

(Scotch)

61. Auld Lang Syne (Club)

(College Boys) (Drinking)

(Farewell) (Scotch)

62. Highland Fling (Bagpipe) (Scotch)

63. Espana-Waltz (South

American) (Spanish)

64. Shepherd's Song (Alpine) (Swiss)

65. Rise, O Servians

66. Ruins of Athens (Turkish)

67. (Entrance) (Opening)

68. (Entrance) (Opening)

69. (Country Scenes) (Entrance)

(Opening) (Village Scene)

70. Pastorale (Country Scenes)

(Farm) (Fireside) (Garden)

(Village Scene)

71. Hush, My Baby (Cradle Song)

(Lullaby)

72. Frog He Would a-Wooing Go

(Children at Play)

73. Fairy Music (Vision or Dream)

74. Jingle Bells (Sleigh Ride)

(Winter Scene)

75. Anvil Polka (Blacksmith)

(Construction) (Factory) (Mill)

76. Traumerei (Reverie) (Fireside)

(Love Scene) (Violinist)

77. Good-Bye, Sweetheart,

Good-Bye (Farewell)

(Love Scene) (Parting)

78. Faithful and True (Bridal Chorus)

79. Wedding March

80. Church Chimes

81. Church Organ

82. Lead Kindly Light (Church Choir)

(Death) (Hymn)

83. Largo (Death)

84. Funeral March

85. Aeroplane/Boat Song (Sea Music)

86. Life on the Ocean Wave (Sailor)

(Sea Music)

87. Rocked in the Cradle

(Burial at Sea) (Sea Music)

88. Misterioso of Foreboding

(Grotesque)

89. Misterioso Pizzicato

90. Fire or Storm (Hurry) (Storm)

91. Agitato (Hurry)

92. Battle Music (Hurry) (Storm)

93. Battle Music (Hurry) (Storm)

94. Eighth Sonata (Agitato) (Hurry)

95. Sonata Pathetique (Agitato)

(Hurry) (Pursuit)

96. Plaintive

97. Assembly (Court, Nobility)

(Grand March)

98. Light Cavalry (Cavalry Charge)

(Horsemen) (Pursuit)

99. Military Polonaise (Assembly)

(Court, Nobility) (Victory)

(Heroic) (Minuet) (Victory)

100. Amaryllis (Gavotte)

(Court, Nobility)

101. Old Virginia (Essence) (Clown)

(Grotesque)

102. Turkey in the Straw (Zip Coon)

(Barnyard) (Reel)

103. Sailor's Hornpipe

(College Hornpipe) (Reel)

104. Chicken Reel (Barnyard) (Reel)

105. Galop (Auto Ride) (Pursuit) (Race)

106. Ballroom Waltz (Overture)

107. Moving Picture Rag (Overture)

|

This large folio was considered by many theatre musicians to be standard equipment for their job. Although a bit daunting in its scope, once the pianist/organist learned how to quickly locate what they needed, they were able to learn it post-haste. In lieu of copy machines, which were still decades off, many musicians simply tore the pages out and reassembled them in a notebook in an order that would better facilitate whatever the film du jour may have been. That may be one of the reasons so few copies of this top-selling musical resource survive today.

Lampe was one of Remick's top arrangers, and a composer of some note as well. This folio represents a number of compiled arrangements of known pieces along with some originals by Lampe, and perhaps other Remick composers as well. Some of the pieces are unaccredited if familiar, which taken in the context of the last 60 years does not necessarily mean they were lifted without acknowledgement from another source. They are familiar to us because even after the movies gained the ability to speak, many composer/arrangers who had been theatre pianists still referred to this book. Many of the themes will be particularly recognizable to fans of Warner Brothers cartoons as house composer Carl Stalling used them with some frequency as appropriate to the mood of the action. They also appear in cartoon soundtracks from other studios, including the mega popular shorts from Walt Disney.

Whereas the smaller Sam Fox Folio uses descriptive titles for each of the works, the Remick is loosely arranged in broad categories using the original titles of tunes (sometimes no title at all) followed by more specific categories for which they are suitable. Fortunately, a cross index by category was provided, much in the same way as would be found in a hymnal, that comparison often reverently noted by the musicians who owned one of each. These pieces range from 8 measures in length to rather substantial pieces when repeats were applied. Of particular fascination is the last piece, The Moving Picture Rag by Lampe, which had been published separately yet has been successfully condensed to a one-page score here.

The Civil War was still fresh in the minds of many Americans a mere fifty years after it ended, and was therefore a popular movie topic since it not only provided stories the populous could relate to, but lots of action as well. A number of the pieces in this folio were well-known chestnuts from that time, and some readily suggested whether the music was from the North or the South. While there is no intentional racism in this resource, it was still present in subtle ways, such as the use of Dixie Land to suggest scenes with blacks in them, and a number of "Indian" or Native American tunes, although they were based on part on true Native American melodies. There is also no shortage of Asian or "Oriental" tunes which were steeped in stereotype, and may actually have helped establish the precedent of traditional musical stereotypes for many decades that followed. Similar but equal treatment was offered for Middle-Eastern nationalities as well in the form of Arabian and "Hindoo" melodies.

For action scenes, apart from the war-oriented vignettes, there were a number of "hurry" pieces, some of which were later used in cartoons or comedies. Know that often when the action involved comic antics, such as with

Mack Sennett's Keystone Kops, many musicians turned to popular songs or rags since those tunes were inherently modern and often whimsical. Just the same, there are a couple of snippets in the folio relating to automobiles and aeroplanes, suggesting speed and daring. When the action was slower or more mysterious, two "misterioso" pieces filled in such scenes very well. In fact, the

Misterioso Pizzicato may be the most recognizable eight measures contained within. (It is also the search for the name and origin of this piece that led me to this book).

Some of the pieces were contrived for filler during specific moments. Whereas silence can be used quite effectively in sound films, it seems that it was hardly golden during this time, and musicians were expected to play for as much of the film as possible. Thus the inclusion of musical interstitial phrases like entrances and exits, classical melodies to accompany pastoral scenes, and even various titles categorized as "plaintive" for quiet times when nothing specific was called for. Oddly enough, sports other than racing are not represented here, so it may be assumed that some of this music was substituted for such scenes, except for baseball where the choice of tune would have been obvious by this time.

The remaining pieces were meant to tug at the emotional involvement of movie patrons in relation to love scenes, moments of passion and pathos, and anything involving children (the AAAAAWWWWW factor). Don't underestimate American patriotic tunes as well as a few from the European continent. And while some may question the inclusion of The Star Spangled Banner as well known as it is now, the piece was still nearly two decades from adoption as the anthem of the United States of America, and therefore played much less frequently than it is now.

So with a little skill you might be able to assemble these pieces as listed by theme and create a soundtrack of your own, even for home movies. While there is no music here applicable to soccer games, XBox tournaments or quiet moments with one's computer, it might still be fun and educational to try replicating the efforts of those pioneering theatre musicians of a century past.

OTHER PIECES USED FOR MOVIE MUSIC

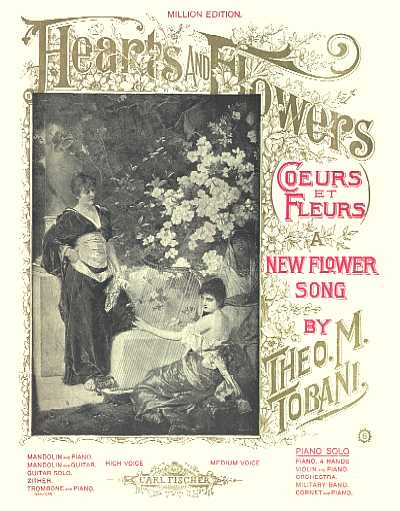

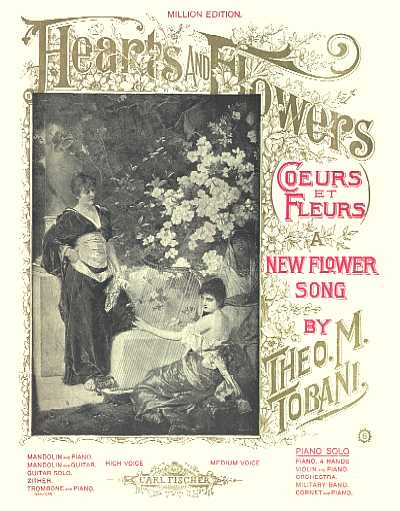

Touted as a "New Flower Song", this is a very beautiful and melodic piece that could be described variously as maudlin or just plain old sappy. Although comedy and adventure stories were the most popular silent films in the 1910s, there were still many dramas dealing with death or loss of some kind. (The media today would label them as "chick flicks", a term I don't endorse under pain of death.) Silent films were usually accompanied by music, played by everything from an orchestra or pianist to automatic instruments such as a multiple-roll orchestrion. Most of the accompanists or orchestrions had a standard stock of pieces to fit the various moods presented in the films.

Hearts and Flowers was present in nearly every library, as it effectively conveyed sorrow and passion so very completely. Mostly classical in nature, it is inclusive of two older pieces,

Adoration and

In A Garden of Melody. The primary theme is written with variations throughout the piece. It becomes more complex in the second theme, where a triplet figure in the right hand is played over a straight rhythm in the left. The middle section has a very nice build to a Chopinesque climax. The lyrics were added in 1899, but the piece was altered substantially to favor them. The version included here is without lyrics.

Hearts and Flowers has been often misunderstood through misuse, and I hope you agree that it is actually stands on its own as a worthy composition of great beauty and pathos.

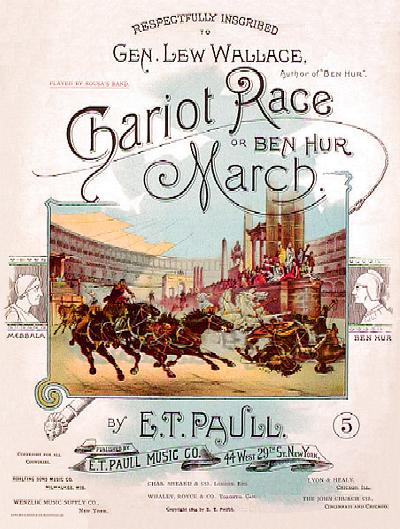

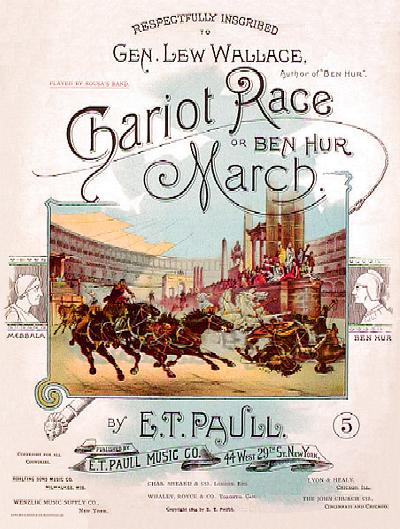

This was Paull's first big hit. It established him through the use of both a beautifully colored cover and the descriptive text inside the music. Marches were gaining in popularity, and this same year would see the composition of

John Phillip Sousa's Stars and Stripes Forever. It was also the year that

General Lew Wallace, bucking opposition from the church, managed to get his novel

Ben Hur - A Tale of the Christ published. This is a fitting tribute to the most exciting part of the book, and indeed of both of the MGM productions of the story; that of the chariot race between once-friends Judah Ben Hur and Messala. For anybody who has not seen the 1925 production starring

Ramon Navarro, I highly recommend finding it. It is part of the Ted Turner movie library, and has many color scenes using the early two-strip Technicolor process that come close to the brilliance of E.T. Paull's vision for his covers. This composition enjoyed a great deal of new popularity when the film was released, and was often used as an accompaniment to the chariot race scene. Note the gradual acceleration near the end of the race, and an ending style that would find a permanent place in many future Paull marches.

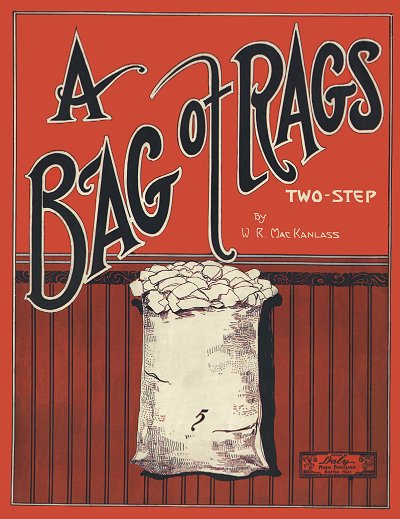

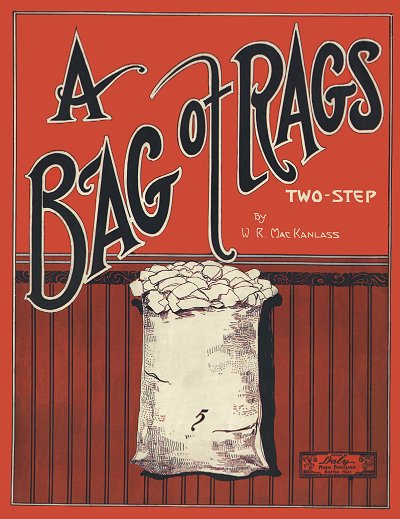

Around the time this piece was written, the movies, or "flickers" were becoming big business. There were very few features of the scope of

D.W. Griffith films being produced. The majority of films released at this time were two-reelers, about 20 minutes long. One of the things that sold best was comedy.

Mack Sennett caught on to this quickly, and produced films featuring

Charlie Chaplin, Ben Turpin, Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle, and the Keystone Kops, named for Sennett's

Keystone Studio. The majority of theatres in the country employed one or two pianists or organists to accompany the films, and a handful had orchestras. It was often the musician's job to produce music that would properly accompany the mood of particular scenes in a film. On occasion, the film company would recommend various pieces.

A Bag of Rags was reportedly the unofficial theme of the Keystone Kops, and it certainly has fit the mood for some of their films that I have played it with. The A section could be described as whimsical, and the B and C sections more melodic. The D section contrasts with a very full and lively sound. Try it against a silent comedy of your choice.

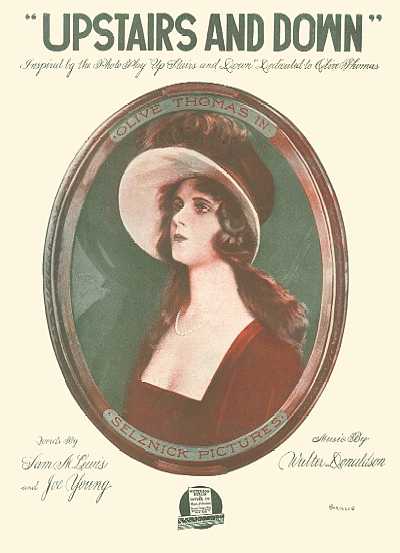

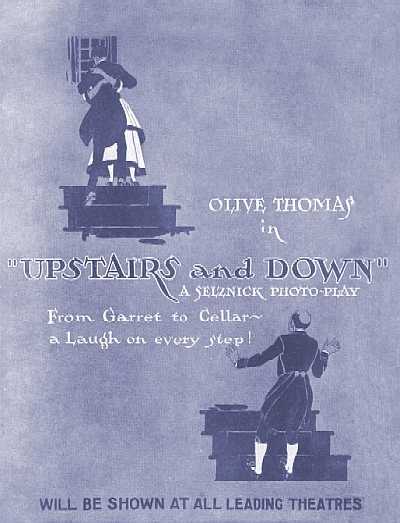

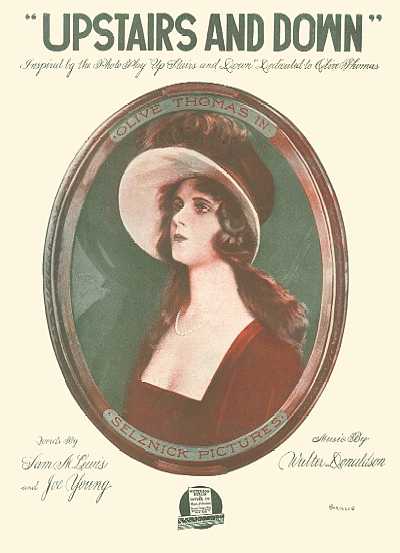

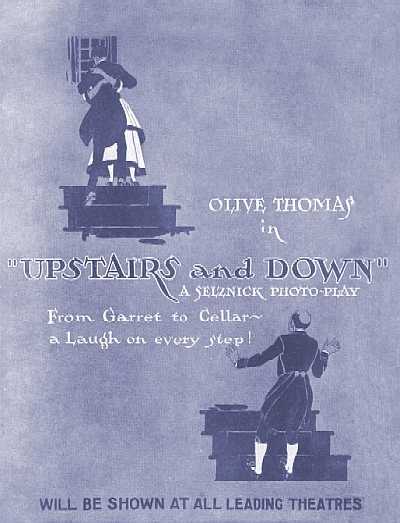

As the 1920s approached and silent movies were moving more into features than simple two-reeler shorts, the studios, and many directors, made various attempts to improve on the technology and presentation of their films. Among the techniques experimented with were tinting of various scenes in a color chosen to convey a certain mood or time of day (2 strip Technicolor was still a few years off), superimposing captions instead of using shots of lettered cards, widescreen presentation, and commissioning works of music written just for a film.

D.W. Griffith had symphonic scores for his two big features,

Intolerance and

Birth of a Nation, and other studios wrote songs that would not only go with a movie, but promote it is well. The first of these has long been acknowledged as 1918's

Mickey by Charles N. Daniels as Neil Moret. As movie songs were suddenly in vogue, the well-known team of Lewis, Young and Donaldson penned this typical ditty for a Selznick Pictures film titled

Upstairs and Down starring the enchanting but troubled actress

Olive Thomas. Unlike songs written later for musicals (an unlikelihood in those silent days), it was simply a popular tune titled to fit the picture. These tunes were often performed by the stars at picture premieres, but usually saw widest distribution in the form of sheet music and audio recordings, a trend that has continued to this day. Miss Kelsey Pederson stood in for Miss Thomas as her singing stunt double for this performance.

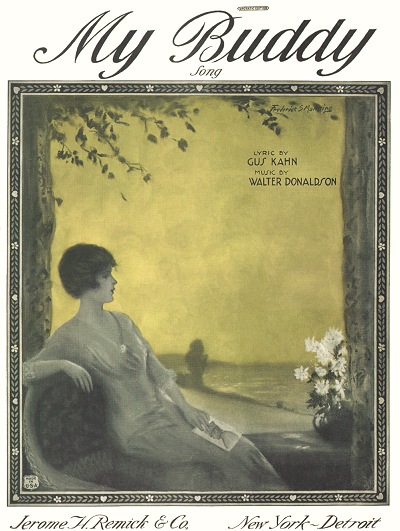

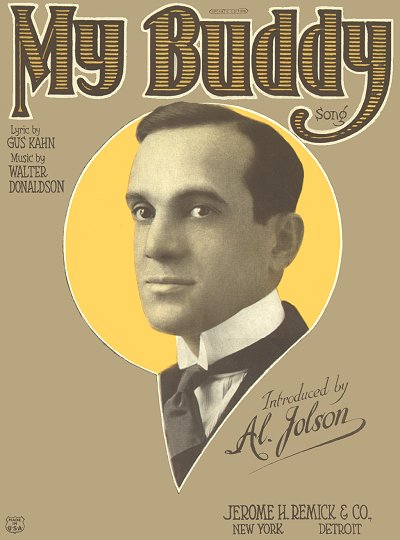

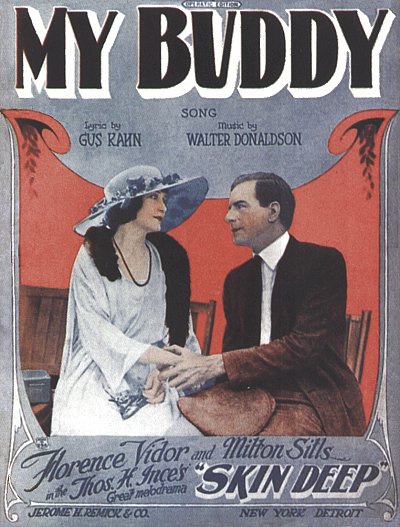

My Buddy

My Buddy Walter Donaldson (M) and Gus Kahn (L) - 1922

Teams worked well, and firms such as

Jerome Remick,

Shapiro, Bernstein and

M. Witmark hired people with the intent of teaming them up. With a good collection of lyricists and composers, if one combination didn't click another would soon be discovered. Such was the case with Donaldson and Kahn, who were responsible for many of the standards composed in the 1920s. Once decent songs were copyrighted (and even some not-too decent ones), the next phase was to push it. There were several methods, some employed simultaneously, to achieve this.

E.T. Paull depended in part on his colorful covers to attract attention to the piece in the store. But just as it has remained since the 1910s in advertising, endorsements are a big key. So the firms also employed people who did nothing but shop the songs to various artists who were either recording or performing on stage, or both. And some artists actually had agents who sought out new songs from the publishers based on a particular topic, the antecedent of musical writing that was still two decades off.

In the case of a piece like My Buddy, it sometimes took a little while for the endorsements or for the tune to catch on. It was still published in a generic format, as shown in the first cover. Once an artist, in this case it was Al Jolson, took a liking to it or recorded it, they would get their name and/or picture on the cover, sometimes in exchange for gratuities of some type. This is clearly shown in the second cover. An additional aspect of endorsement started to come into use in the late 1910s - that of associating a song with a movie or stage production. While there were obviously no soundtracks to movies until the late 1920s, a director or producer, sometimes at the insistence of a publisher (financial or otherwise) would request that a thematic piece be played at a certain moment in the movie, thus providing continuity between performances and another method of selling the song (shown by the third cover). Copies would, of course, be available in the lobby after the performance. My Buddy was thus introduced to the public this way, and has long remained a sentimental favorite based largely on the quality of the tune. Ella Fitzgerald sang this to a weeping crowd at the funeral of Harlem drumming legend Chick Webb in June of 1939.

Bibliography and Recommended Reading or Viewing

Click on a cover image to locate and order it.

The Parade's Gone By... Kevin Brownlow

[©1983, University of California Press]

Originally compiled in the 1960s, the author was fortunate enough to have the ear of many of the original stars of the silent era who granted him remarkable interviews detailing the filmmaking process and the early days of Hollywood before sound.

Silent Films, 1877 to 1996 Robert K. Klepper

[©1999, McFarland & Company]

More of a reference guide than anything else, this volume provides a general synopsis and comments on 646 silent films covering 120 years.

American Silent Film William K. Everson

[©1978, 1998, DaCapo Press]

While focused largely on serious or dramatic efforts of early 20th century film, there is enough about the process from writing to distribution to appease most any early film buff. This is a revision of an earlier release.

A-Z of Silent Film Comedy Glenn Mitchell

[©1999, Brasseys, Inc.]

Perhaps one of the best overviews of silent comedy film stars and some of the films themselves. This book does not replace individual biographies of the stars, but is a good starting point.

Music and the Silent Film: Contexts and Case Studies, 1895-1924 Kevin Brownlow

[©1997, Oxford University Press]

An analytical study of five scores written specifically to accompany five silent features, this book is a good study guide as to the requirement to create the proper moods and synchronize live music to the action.

Nickelodeon Theatres and Their Music Q. David Bowers

[©1999, Scarecrow Press]

A fabulous view of the rise of movie houses, including the methods of music reproduction used in theatres of varying sizes.

Slapstick Encyclopedia (Volumes 1-10)

[©2002, Image Entertainment]

Compiled by film restorer David Shepherd this is the best balanced collection of silent comedies available. Updated for DVD from the VHS edition in a 5-disc set, there are 18+ hours of first rate entertainment with fresh soundtracks. Good news - Mr. Shepherd tells me he is working on Slaptsick Encyclopedia 2 for future release.

The Movies Begin - A Treasury of Early Cinema 1894 to 1913

[©2002, Kino International]

This has all you would expect and more from the early days of cinema as collected by David Shepherd, including Georges Méliès' Le Voyage à travers l'impossible, The Great Train Robbery, and dozens of very short subjects from the European and American continents. A 5-disc DVD set, it is a great educational resources as well.

NOTE: To those looking for silent film releases on either video or DVD. In many ways you get what you pay for. I highly endorse anything restored by David Shepherd on either Image Entertainment or Kino International releases, as he has gone to an inordinate amount of effort to locate the best quality prints as well as footage thought to be forever lost. His collections are also well-grouped and logical. He furthermore has new soundtracks recorded when possible and insists on well-developed and thematically appropriate tracks for each film.

By the same token, I will caution you against silent film collections put out by Madacy Entertainment since they are often rehashes of older pre-digital restoration recorded material, have soundtracks that have little to do with the era and no logical synchronization to the action, and are often missing varying chunks of footage that are found on Image or Kino for just a little higher investment. This is not to slight the management or integrity of Madacy - just to point out that there are alternatives in this instance which are superior to their product. Read the reviews on Amazon.Com for each product to verify this contention.

Bill Edwards

Loading Page. Please Wait...

Loading Page. Please Wait...

Player Pianos

Player Pianos

Phonographs and Recording

Phonographs and Recording

Sounds of the Silents

Sounds of the Silents

Ragtime & the Economy

Ragtime & the Economy

Ragtime and MIDI

Ragtime and MIDI

In many cases, such as with the Remick Folio below, theatre musicians used a combination of original pieces and snippets of other well-known works from popular songs to classical music. In an effort to be both specific to the task and to avoid copyright entanglements, Zamecnik composed the contents of this folio from scratch. Also, many of the common melodies used for Civil War or similar scenes were widely available and well-known, and where that didn't work the pianist could certainly fill in a waltz or a rag. In this folio, Zamecnik successfully addresses the issues of appropriate music to help bolster the action or emotional content of what was on the screen at any particular time. It also provided a nice style template for pianists who were less experienced and lacked the improvisational variety necessary to keep the music fresh. Zamecnik further designed it so that the pieces were not out of the technical reach of the average semi-professional musician.

In many cases, such as with the Remick Folio below, theatre musicians used a combination of original pieces and snippets of other well-known works from popular songs to classical music. In an effort to be both specific to the task and to avoid copyright entanglements, Zamecnik composed the contents of this folio from scratch. Also, many of the common melodies used for Civil War or similar scenes were widely available and well-known, and where that didn't work the pianist could certainly fill in a waltz or a rag. In this folio, Zamecnik successfully addresses the issues of appropriate music to help bolster the action or emotional content of what was on the screen at any particular time. It also provided a nice style template for pianists who were less experienced and lacked the improvisational variety necessary to keep the music fresh. Zamecnik further designed it so that the pieces were not out of the technical reach of the average semi-professional musician. Hearts and Flowers (Coeurs et Fleurs)

Hearts and Flowers (Coeurs et Fleurs)

Touted as a "New Flower Song", this is a very beautiful and melodic piece that could be described variously as maudlin or just plain old sappy. Although comedy and adventure stories were the most popular silent films in the 1910s, there were still many dramas dealing with death or loss of some kind. (The media today would label them as "chick flicks", a term I don't endorse under pain of death.) Silent films were usually accompanied by music, played by everything from an orchestra or pianist to automatic instruments such as a multiple-roll orchestrion. Most of the accompanists or orchestrions had a standard stock of pieces to fit the various moods presented in the films. Hearts and Flowers was present in nearly every library, as it effectively conveyed sorrow and passion so very completely. Mostly classical in nature, it is inclusive of two older pieces, Adoration and In A Garden of Melody. The primary theme is written with variations throughout the piece. It becomes more complex in the second theme, where a triplet figure in the right hand is played over a straight rhythm in the left. The middle section has a very nice build to a Chopinesque climax. The lyrics were added in 1899, but the piece was altered substantially to favor them. The version included here is without lyrics. Hearts and Flowers has been often misunderstood through misuse, and I hope you agree that it is actually stands on its own as a worthy composition of great beauty and pathos.

Touted as a "New Flower Song", this is a very beautiful and melodic piece that could be described variously as maudlin or just plain old sappy. Although comedy and adventure stories were the most popular silent films in the 1910s, there were still many dramas dealing with death or loss of some kind. (The media today would label them as "chick flicks", a term I don't endorse under pain of death.) Silent films were usually accompanied by music, played by everything from an orchestra or pianist to automatic instruments such as a multiple-roll orchestrion. Most of the accompanists or orchestrions had a standard stock of pieces to fit the various moods presented in the films. Hearts and Flowers was present in nearly every library, as it effectively conveyed sorrow and passion so very completely. Mostly classical in nature, it is inclusive of two older pieces, Adoration and In A Garden of Melody. The primary theme is written with variations throughout the piece. It becomes more complex in the second theme, where a triplet figure in the right hand is played over a straight rhythm in the left. The middle section has a very nice build to a Chopinesque climax. The lyrics were added in 1899, but the piece was altered substantially to favor them. The version included here is without lyrics. Hearts and Flowers has been often misunderstood through misuse, and I hope you agree that it is actually stands on its own as a worthy composition of great beauty and pathos. The Chariot Race, or, Ben Hur March

The Chariot Race, or, Ben Hur March  This was Paull's first big hit. It established him through the use of both a beautifully colored cover and the descriptive text inside the music. Marches were gaining in popularity, and this same year would see the composition of John Phillip Sousa's Stars and Stripes Forever. It was also the year that General Lew Wallace, bucking opposition from the church, managed to get his novel Ben Hur - A Tale of the Christ published. This is a fitting tribute to the most exciting part of the book, and indeed of both of the MGM productions of the story; that of the chariot race between once-friends Judah Ben Hur and Messala. For anybody who has not seen the 1925 production starring Ramon Navarro, I highly recommend finding it. It is part of the Ted Turner movie library, and has many color scenes using the early two-strip Technicolor process that come close to the brilliance of E.T. Paull's vision for his covers. This composition enjoyed a great deal of new popularity when the film was released, and was often used as an accompaniment to the chariot race scene. Note the gradual acceleration near the end of the race, and an ending style that would find a permanent place in many future Paull marches.

This was Paull's first big hit. It established him through the use of both a beautifully colored cover and the descriptive text inside the music. Marches were gaining in popularity, and this same year would see the composition of John Phillip Sousa's Stars and Stripes Forever. It was also the year that General Lew Wallace, bucking opposition from the church, managed to get his novel Ben Hur - A Tale of the Christ published. This is a fitting tribute to the most exciting part of the book, and indeed of both of the MGM productions of the story; that of the chariot race between once-friends Judah Ben Hur and Messala. For anybody who has not seen the 1925 production starring Ramon Navarro, I highly recommend finding it. It is part of the Ted Turner movie library, and has many color scenes using the early two-strip Technicolor process that come close to the brilliance of E.T. Paull's vision for his covers. This composition enjoyed a great deal of new popularity when the film was released, and was often used as an accompaniment to the chariot race scene. Note the gradual acceleration near the end of the race, and an ending style that would find a permanent place in many future Paull marches. A Bag Of Rags

A Bag Of Rags

Around the time this piece was written, the movies, or "flickers" were becoming big business. There were very few features of the scope of D.W. Griffith films being produced. The majority of films released at this time were two-reelers, about 20 minutes long. One of the things that sold best was comedy. Mack Sennett caught on to this quickly, and produced films featuring Charlie Chaplin, Ben Turpin, Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle, and the Keystone Kops, named for Sennett's Keystone Studio. The majority of theatres in the country employed one or two pianists or organists to accompany the films, and a handful had orchestras. It was often the musician's job to produce music that would properly accompany the mood of particular scenes in a film. On occasion, the film company would recommend various pieces. A Bag of Rags was reportedly the unofficial theme of the Keystone Kops, and it certainly has fit the mood for some of their films that I have played it with. The A section could be described as whimsical, and the B and C sections more melodic. The D section contrasts with a very full and lively sound. Try it against a silent comedy of your choice.

Around the time this piece was written, the movies, or "flickers" were becoming big business. There were very few features of the scope of D.W. Griffith films being produced. The majority of films released at this time were two-reelers, about 20 minutes long. One of the things that sold best was comedy. Mack Sennett caught on to this quickly, and produced films featuring Charlie Chaplin, Ben Turpin, Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle, and the Keystone Kops, named for Sennett's Keystone Studio. The majority of theatres in the country employed one or two pianists or organists to accompany the films, and a handful had orchestras. It was often the musician's job to produce music that would properly accompany the mood of particular scenes in a film. On occasion, the film company would recommend various pieces. A Bag of Rags was reportedly the unofficial theme of the Keystone Kops, and it certainly has fit the mood for some of their films that I have played it with. The A section could be described as whimsical, and the B and C sections more melodic. The D section contrasts with a very full and lively sound. Try it against a silent comedy of your choice.

As the 1920s approached and silent movies were moving more into features than simple two-reeler shorts, the studios, and many directors, made various attempts to improve on the technology and presentation of their films. Among the techniques experimented with were tinting of various scenes in a color chosen to convey a certain mood or time of day (2 strip Technicolor was still a few years off), superimposing captions instead of using shots of lettered cards, widescreen presentation, and commissioning works of music written just for a film. D.W. Griffith had symphonic scores for his two big features, Intolerance and Birth of a Nation, and other studios wrote songs that would not only go with a movie, but promote it is well. The first of these has long been acknowledged as 1918's Mickey by Charles N. Daniels as Neil Moret. As movie songs were suddenly in vogue, the well-known team of Lewis, Young and Donaldson penned this typical ditty for a Selznick Pictures film titled Upstairs and Down starring the enchanting but troubled actress Olive Thomas. Unlike songs written later for musicals (an unlikelihood in those silent days), it was simply a popular tune titled to fit the picture. These tunes were often performed by the stars at picture premieres, but usually saw widest distribution in the form of sheet music and audio recordings, a trend that has continued to this day. Miss Kelsey Pederson stood in for Miss Thomas as her singing stunt double for this performance.

As the 1920s approached and silent movies were moving more into features than simple two-reeler shorts, the studios, and many directors, made various attempts to improve on the technology and presentation of their films. Among the techniques experimented with were tinting of various scenes in a color chosen to convey a certain mood or time of day (2 strip Technicolor was still a few years off), superimposing captions instead of using shots of lettered cards, widescreen presentation, and commissioning works of music written just for a film. D.W. Griffith had symphonic scores for his two big features, Intolerance and Birth of a Nation, and other studios wrote songs that would not only go with a movie, but promote it is well. The first of these has long been acknowledged as 1918's Mickey by Charles N. Daniels as Neil Moret. As movie songs were suddenly in vogue, the well-known team of Lewis, Young and Donaldson penned this typical ditty for a Selznick Pictures film titled Upstairs and Down starring the enchanting but troubled actress Olive Thomas. Unlike songs written later for musicals (an unlikelihood in those silent days), it was simply a popular tune titled to fit the picture. These tunes were often performed by the stars at picture premieres, but usually saw widest distribution in the form of sheet music and audio recordings, a trend that has continued to this day. Miss Kelsey Pederson stood in for Miss Thomas as her singing stunt double for this performance.

This piece provides a nice opportunity to get a glimpse into the hit-creation process that had become such a vital element of Tin Pan Alley in the 1920s. The "Alley" was actually comprised of a number of publishers centrally located in New York City, although there were also some in Chicago and on the West Coast of the US. The sole purpose of many of these publishers had shifted from the 1880s edict of producing good music for performance or home use to that of creating massive hits that would spawn sales of phonograph records, piano rolls, sheet music, and royalties from many different sources. In essence, composers were hired to turn out hits, and some even had quotas to fulfill. Whether it be a sentimental weeper, some new dance craze, or a novelty number, getting it out to the public and pushing it in exchange for revenue (most of it going to the publisher and not the composers) was the focus of many of the firms in the music business up through even the mid-1960s.

This piece provides a nice opportunity to get a glimpse into the hit-creation process that had become such a vital element of Tin Pan Alley in the 1920s. The "Alley" was actually comprised of a number of publishers centrally located in New York City, although there were also some in Chicago and on the West Coast of the US. The sole purpose of many of these publishers had shifted from the 1880s edict of producing good music for performance or home use to that of creating massive hits that would spawn sales of phonograph records, piano rolls, sheet music, and royalties from many different sources. In essence, composers were hired to turn out hits, and some even had quotas to fulfill. Whether it be a sentimental weeper, some new dance craze, or a novelty number, getting it out to the public and pushing it in exchange for revenue (most of it going to the publisher and not the composers) was the focus of many of the firms in the music business up through even the mid-1960s.